Eugene Andrew “Gene” Cernan, Captain, United States Navy (retired) and former NASA astronaut, passed away on Monday, January 16th 2017 at the age of 82. The commander of Apollo 17, he was – and currently remains – the last man to walk on the surface of the Moon, in what was arguably the most significant of the Apollo lunar missions.

Born in Chicago, Illinois in March, 1934, he attended Purdue University, Indiana, where he gained a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering in 1956. While at the university. he took a commission as an Ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps. Following his graduation, he attended U.S. Naval Flight Training, qualifying as an attack pilot, and went on to log more than 4,000 flying hours in jet aircraft and completed over 200 aircraft carrier landings.

In 1963, Cernan completed his education under the auspices of the US Navy, obtaining a Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School. Later that same year, he was selected by NASA as a part of their third intake of Astronaut Candidates, and participated in both the Gemini and Apollo programmes.

His first flight into space, aboard Gemini 9A started with a tragedy. The original Gemini 9 flight had been scheduled for Elliot See and Charlie Bassett. However, when they were unfortunately killed when their NASA aircraft crashed at the end of February 1966, the mission was re-rostered as Gemini 9A, and Cernan and his flight partner, Thomas Stafford, were promoted from back-up to prime crew.

Gemini 9A was to prove a mission plagued with misfortune. The first attempt to launch the mission, in May 1966 had to be scrubbed when the uncrewed Agena Target Vehicle Gemini 9A would rendezvous and dock with once in orbit was lost not long after launch. This required a delay while a second Agena was prepared for flight, being launched on June 1st, 1966. However, once in orbit, telemetry from the vehicle suggested a launch shroud had not been correctly jettisoned.

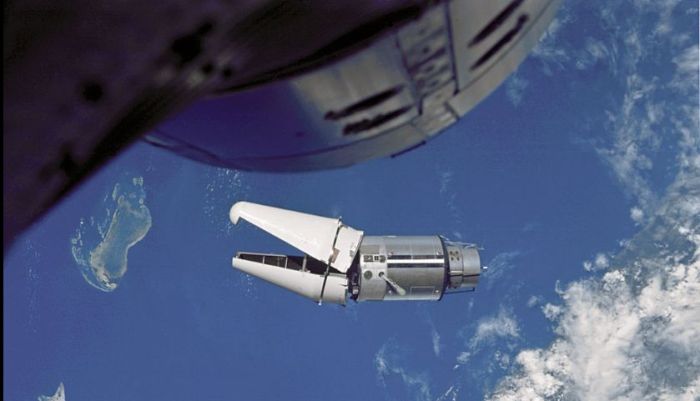

On approaching the Agena following their launch on June 3rd, Stafford and Cernan confirmed the sections of the shroud, although open, had failed to detach, leaving the vehicle looking – in Stafford’s words – “Like an angry alligator out here rotating around”. He and Cernan indicated they were willing to carefully approach the Agena and try to nudge the shroud elements clear of the docking adapter, but mission control nixed the idea, fearing the Gemini vehicle might be damaged in the process. Instead, the crew rehearsed docking runs with the target vehicle and tested rendezvous abort procedures.

On the third day of the flight, Cernan became the third man (and America’s second) to walk in space. However, this part of the mission also proved troublesome. The Gemini spacesuits were not water-cooled, and had to be “inflated” prior to egressing the vehicle. Cernan found the latter made the suit almost completely inflexible and a serious impediment to his movement. This meant he had to exert himself a lot more, and because the suit had no proper cooling, he face the genuine risk of suffering heat prostration.

Nor was this all; the build-up of heat meant his helmet faceplate fogged to the point where he could barely see, and there were serious concerns about him getting back into the Gemini. His EVA was curtailed without all goals being met, and after 128 minutes in space, Cernan eventually made it back inside the spacecraft. As a result of this experience, the Apollo spacesuits were redesigned to incorporate an undergarment using a water circulation system to cool the wearer – and approach still used in modern space suits.

Cernan next flew in space in May 1969 as part of the final Apollo dress-rehearsal mission for an actual landing on the Moon. Apollo 10, which saw Cernan and Stafford again fly together, and joined by John Young, became the second crewed mission to orbit the Moon (the first being Apollo 8, in December 1968), and the fourth crewed flight of Apollo overall. The focus of the mission was for Stafford and Cernan to pilot the Lunar Module to just 15.6 km (8.4 mi) above the lunar surface, gathering critical data which would allow the powered descent systems aboard future Lunar Modules to be correctly calibrated for their missions.

In most respects, the Apollo 10 Lunar Module was fully capable of flying a mission to the surface of the Moon – it just lacked sufficient propellent in its ascent engine fuel tanks to make a successful flight back to rendezvous with the Command Module. This later prompted Cernan to joke, “A lot of people thought about the kind of people we were: ‘Don’t give those guys an opportunity to land, ’cause they might!’ So the ascent module, the part we lifted off the lunar surface with, was short-fuelled. The fuel tanks weren’t full. So had we literally tried to land on the Moon, we couldn’t have gotten off.”

Apollo 10 reached lunar orbit on May 21st, 1969, three days after launch, and remained there for a further three days, completing the Lunar Module tests in the process, before returning to Earth. It was a mission which set both records and firsts. It was the first (and only) Apollo Saturn V mission to launch from Pad 39B at Kennedy Space Centre; it was the first (of only two, the other being Apollo 11) Apollo missions to comprise veterans of previous missions into space.