2026 is set to get off to an impressive start for US-led ambitions for the Moon, with the first three months intended to see the launch and completion of two key missions in the Artemis programme.

In fact, if the principal players in both missions get their way, the missions could be completed before the end of February 2026 and between them signal the opening of the gates that lead directly to the return of US astronauts to the Moon in 2028. Those two missions are the flight of the Blue Origin Pathfinder Mission to the lunar surface, and the first crewed flight to the vicinity of the Moon since the end of the Apollo era: Artemis 2.

Blue Moon Pathfinder

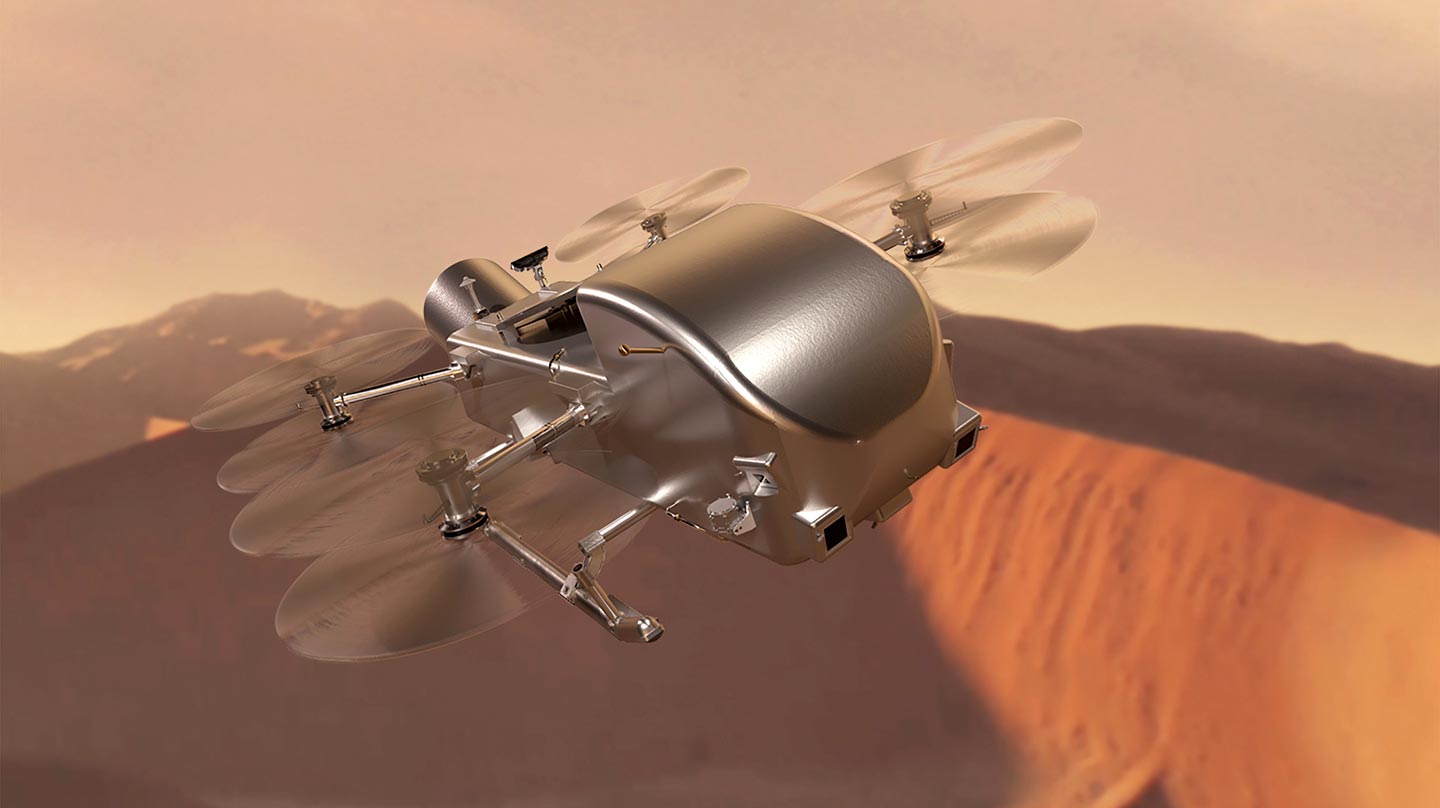

As I’ve previously noted in this column, Blue Moon Pathfinder is intended to fly a prototype of the Blue Moon 1 cargo lander to the Moon’s South Polar Region to demonstrate key elements and capabilities vital to both the Blue Moon Mark 1 and its larger, crew-capable sibling, Blue Moon Mark 2.

These goals include: the firing / re-firing of the BE-7 engine intended for use in both versions of Blue Moon; full use of the planned cryogenic power and propulsion systems; demonstration of the core avionics and automated flight / landing capabilities common to both Blue Moon Mark 1 and Blue Moon Mark 2; evaluate the continuous downlink communications; and confirm the ability of Blue Moon landers to guide themselves to a targeted landing within 100 metres of a designated lunar touchdown point.

Success with the mission could place Blue Origin and Blue Moon in a position where they might take the lead in the provisioning of a human landing system (HLS) to NASA in time for the Artemis 3 mission, currently aiming for a 2028 launch. A similar demonstration flight of Blue Moon Mark 2 is planned for 2027, involving the required Transporter “tug” vehicle needed to get Blue Moon Mark 2 to the Moon. If successful, this could potentially seal the deal for Blue Moon in this regard, given both they and SpaceX must undertake such a demonstration prior to Artemis 3 – and currently, SpaceX has yet to demonstrate the viability of any major component of the HLS design beyond the Super Heavy booster.

Of course, as others have found to their cost in recent years, making an automated landing on the Moon isn’t quite as easy as it may sound, so the above does come with a sizeable “if” hanging over it.

The Blue Moon landers are between them intended to provide NASA with a flexible family of landing vehicles, with Blue Moon Mark 1 capable of delivering up to 3 tonnes of materiel to the Moon, and Blue Moon Mark 2 crews of up to four (although 2 will be the initial standard complement) or between 20 tonnes (lander to be re-used) or 30 tonnes (one-way mission) of cargo.

Currently, the Blue Moon Pathfinder flight is scheduled for Q1 2026 – and could potentially take place before the end of January.

Artemis 2: Four People Around the Moon and Back

Artemis 2, meanwhile is targeting a February 5th, 2026 launch. It will see the first crew-carrying Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) head to cislunar space with three Americans and a Canadian aboard in a 10-11 day mission intended to thoroughly test the vehicle’s crew systems, life support, etc. Despite all the negative (and in part unfair) criticism of the Orion system and its SLS launch vehicle, 21 of the 22 pre-launch milestones have now been met. This leaves only the roll-out of the completed SLS / Orion stack to the launch pad and the full booster propellant tanking testing order for the green light to be given to go ahead with a launch attempt.

No date has been publicly released for the roll-out, but given the issues experienced with Artemis 1, when helium purge leaks caused problems during the propellant load testing, it is likely that even with the high degree of confidence in the updates made to the propellant loading systems since Artemis 1, NASA will want as much time as possible to carry out the test ahead of the planned launch date.

Whilst Orion did fly to the Moon in 2022, the vehicle being used for Artemis 2 is very different to the one used in Artemis 1. This will be the first time Orion will fly all of the systems required to support a crew of 4 on missions of between 10 and 21 days in space (as is the initial – and possibly only, giving the calls to cancel Orion, despite its inherent flexibility as a crewed vehicle – requirements for the system). As such, Artemis 2 is intended to be a comprehensive test of all of the Orion systems, and particularly the ECLSS – Environmental Control and Life Support System; the vehicle’s Universal Waste Management System (UWMS – or “toilet”, to put it in simpler terms); the food preparation system and the overall crew living space for working, eating, resting and sleeping.

These tests are part of the reason the mission is set to have a 10-11 day duration compared to the average of 3 days the Apollo missions took to reach, and then return from, the vicinity of the Moon: NASA want to carry out as comprehensive a series of tests as possible on Orion “real” conditions prior to committing to launching the 30-day Artemis 3 mission.

The mission will also be a critical test for Orion’s heat shield. During Artemis 1, the Orion heat shield suffered considerable damage during re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, in what was called “char loss” – deep pitting in the heat shield material. Analysis of the damage reviewed the gouges to be the result of “spalling”. In short, in order to shed some of its enormous velocity prior to making a full re-entry into the atmosphere, Orion had been designed to make several “skips” into and out of the atmosphere, allowing it to lose speed without over-stressing the heat shield all at once.

Unfortunately, the method used to manufacture the original heat shields resulted in trace gases being left within the layers of ablative material. When repeatedly exposed to rapid heating as the Artemis 1 Orion vehicle skipped in and out of the upper atmosphere, these gases went through a rapid cycle of expansion, literally blowing out pieces of the heat shield, which were then further exacerbated as the vehicle make its actual re-entry, resulting in the severe char loss.

As a result of the Artemis 1 heat shield analysis, those now destined to be used on Artemis 3 onwards will be put through a different layering process to reduce the risk of residual gases becoming trapped in the material. However, because the heat shield for Artemis 2 was already cast, the decision was made to fly it with the mission, but to re-write the Orion’s atmospheric re-entry procedures and software to limit the number of atmospheric skips and the initial thermal stress placed on the heat shield, thus hopefully preventing the spalling.

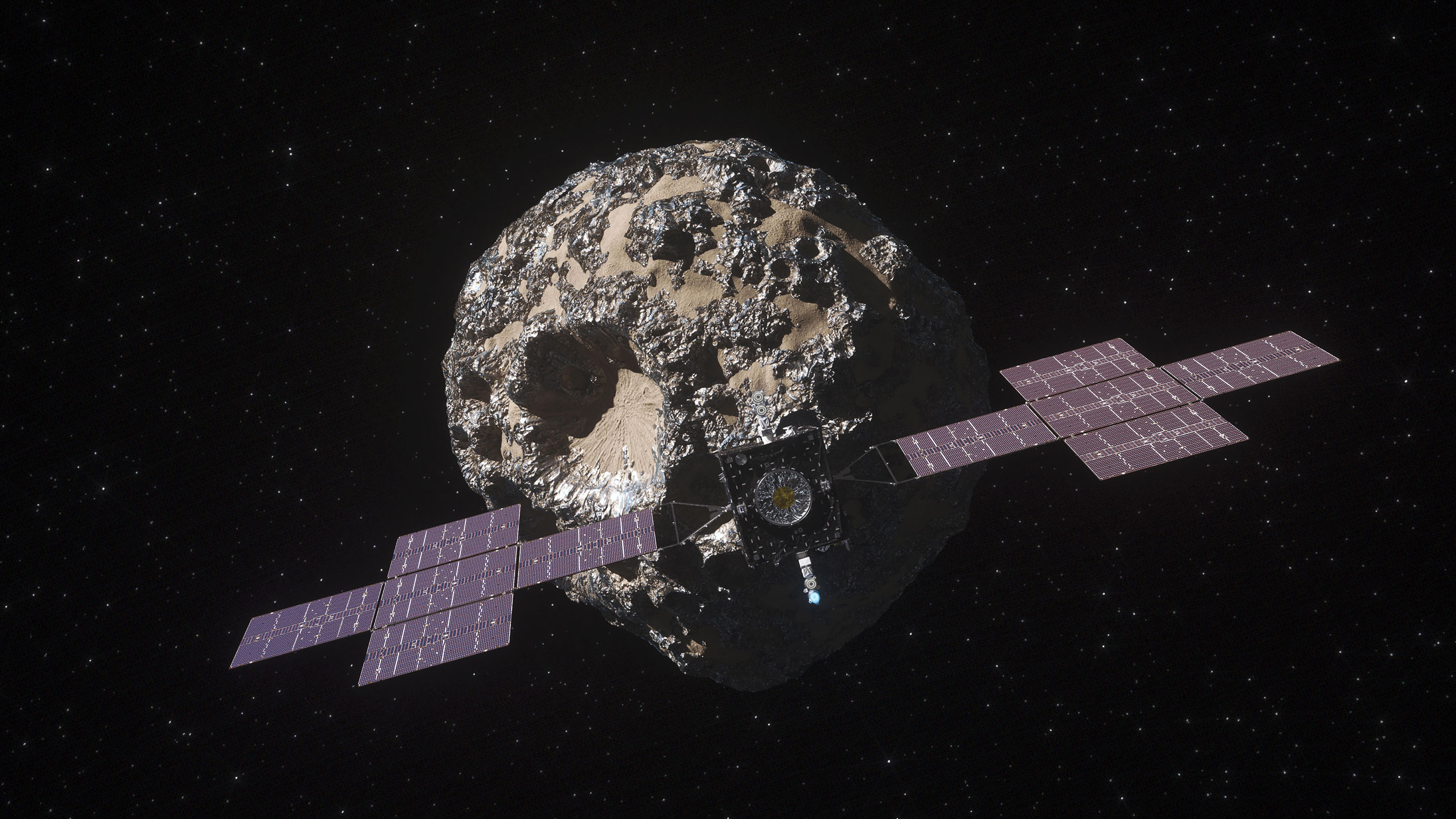

The Orion vehicle to fly on Artemis 2 is the second fully-completed Orion system – that is, capsule plus European Service Module – and the first vehicle to ne formally named: Integrity. It is functionally identical to the vehicles that will fly on Artemis 3 onwards, with the exception that it is not equipped with the forward docking module the latter vehicles will require to mate with their HLS vehicles and / or the Gateway station.

The SLS booster to be used in the mission is the second in a series of five such boosters being built. Three of these – the vehicle used with Artemis 1 and those for Artemis 2 and 3 are of the initial Block 1 variant, using the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) as their upper stages. This is an evolution of the well-proven – but payload limited – Delta Cryogenic Second Stage (DCSS) developed in the 1990s, and powered by a single RL-10B motor.

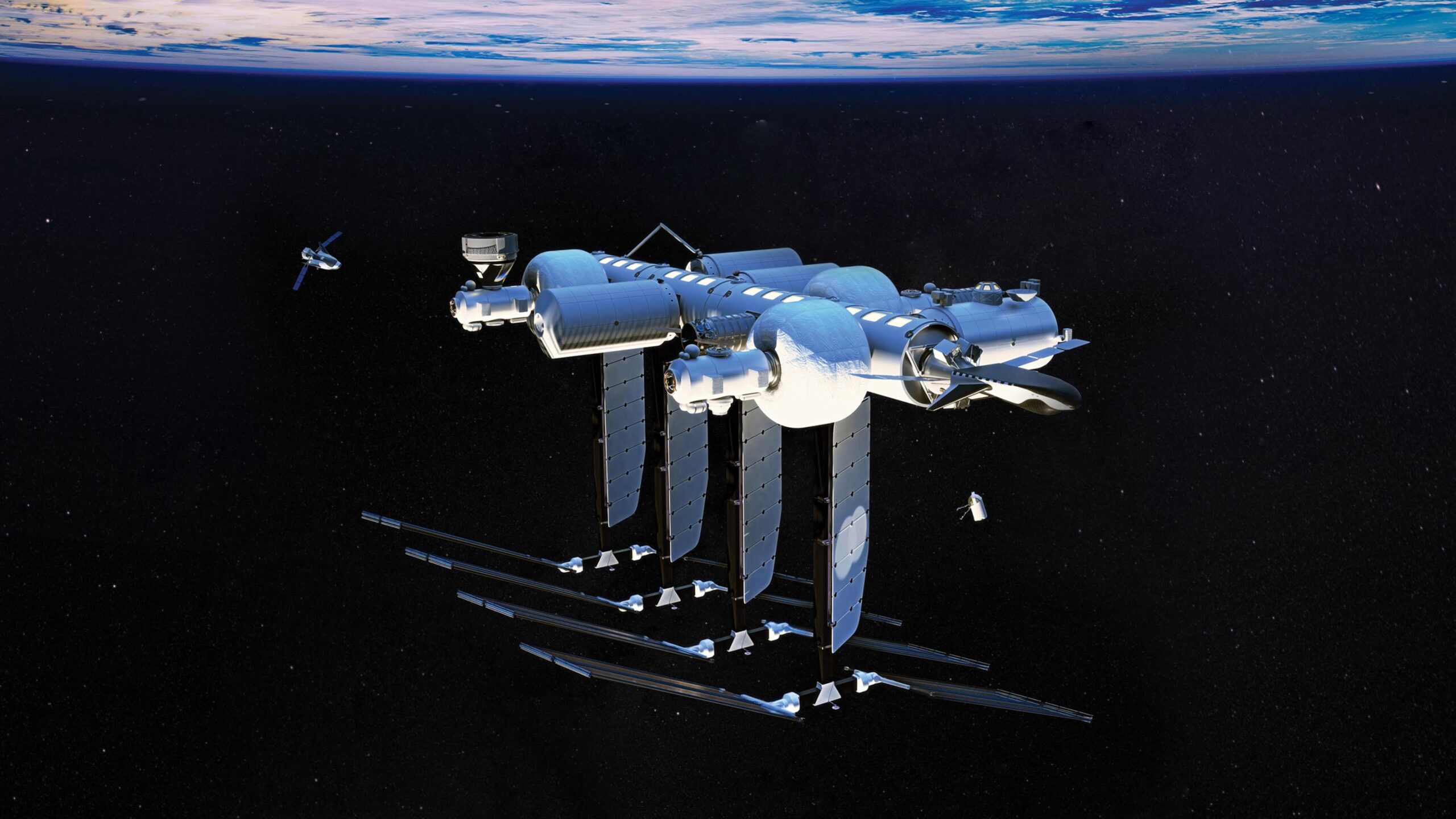

Artemis 4 and 5 are intended to be Block 1B versions of SLS, using the purpose-built and more powerful Exploration Upper Stag (EUS), powered by 4 of the uprated RL-10C version of the same engine, enabling them to lift heavier payloads to orbit and the Moon. This means that both Artemis 4 and Artemis 5 will each lift both an Orion MPCV with a crew of 4 and a 10-tonne module intended for the Gateway station intended to be the lunar-orbiting waystation for crews heading to the Moon from Artemis 4 onwards.

However, to return to Artemis 2: as noted, it will be the second SLS rocket to be launched, and like Artemis 1, will fly using the venerable and (up until SLS at least) reusable RS-25 motor developed by Rocketdyne for the US space shuttle vehicles. Sixteen of these engines survived the end of the shuttle programme, and Artemis 2 will see the use of both the most reliable of them ever built. and the only one to be built for the shuttle programme but never used.

Engine 2047 has flown more missions than any other RS-25 – 15 shuttle missions in which it gained a reputation for being the most reliable space shuttle main engine (SSME), consistently out-performing all other motors to come off the original production line. It proved so reliable that not only did it help lift 76 astronauts from the US and around the world into orbit, it was often specifically requested for complex mission such as those involved construction of the International Space Station and servicing the Hubble Space Telescope. By contrast, engine 2062 will be making its first (and last) flight on Artemis 2, being the last of the original RS-25’s off the production line.

Such is the engineering behind these engines and their control systems that is worth spending a few paragraphs on exactly how they work at launch. While it may seem that all the motors on a multi-engine rocket fire at the same time, this is often not the case because of issues such as the sudden dynamic stress placed on the vehicle’s body and matter of balance, as well as the need to ensure the engines are running correctly.

For the SLS system, for example, engine preparation for launch starts when the propellant tanks are being filled, when some liquid hydrogen is allowed to flow through the engines and vent into the atmosphere in a process called chill down. This cools the critical parts of the engines – notably the high pressure turbopumps – to temperatures where they can handle the full flow of liquid hydrogen or liquid oxygen without suffering potentially damaging thermal shock.

Actual ignition starts at 6.5 seconds prior to lift-off, when the engines fire in sequence – 1, 4, 2, and 3 – a few milliseconds apart (for Artemis 2 engine 2047 is designated flight engine 1 and 2062 flight engine 2, and so these will fire first and second). Brief though the gap is, it is enough to ensure balance is maintained for the entire vehicle and the four engines can run up to power without creating any damaging harmonics between them.

The low and high pressure turbopumps on all four engines then spool up to their operating rates – between 25,000 and 35,000 rpm in the case of the latter – to deliver propellants and oxidiser to the combustion chamber at a pressure of 3,000psi – that’s the equivalent of being some 4 km under the surface of the ocean. During the initial sequence, only sufficient liquid oxygen is delivered to the engines to ignite the flow of liquid hydrogen, causing the exhaust from the engines to burn red. This high pressure exhaust is then directed as thrust through the engine nozzles, meeting the air just beyond the ends of the engine bells.

The counter-pressure of the ambient air pressure is enough to start pushing some of the exhaust gases back up into the engine nozzles, causing what is called a separation layer, visible as a ring of pressure in the exhaust plume. This back pressure, coupled with the thrust of the engines, is enough to start flexing the engine exhaust nozzles, which in turn can cause the exhaust plume on each engine to be deflected by up to 30 centimetres.

To counter this, the flight control computers initiate a cycle of adjustments throughout each engine, which take place every 20 milliseconds. These adjust the propellant flow rate, turbopump speeds, combustion chamber pressure and the movement of the engines via their gimbal systems in order to ensure all of the engines are firing smoothly and all in a unified direction and pressure, symbolised by a “half diamond” of blue-tinged exhaust (the colour indicating the flow of liquid oxygen) as the separation layer is broken, the thrust of the engines fully overcoming ambient air pressure resistance. All this occurs in less than four seconds, the flight computers able to shut down the engines if anything untoward is monitored. Then, as the countdown reaches zero, the solid rocket boosters (SRBs) ignite and the vehicle launches.

Once underway, Artemis 2 will carry its crew of 4 into Earth orbit for a 24-hour vehicle check-out phase, during which the orbit’s apogee and perigee are raised. Check-out involves the crew completing a series of tests on the vehicle and its systems, including piloting it, both before and after the ICPS is jettisoned. Completion of this initial check-out phase will conclude with the firing on the ESM’s motor to place Orion on a course for the Moon.

The flight to the Moon will be undertaken using what is called a free return trajectory. That is, a course that will allow the vehicle to loop around the Moon, using its gravity to swing itself back onto a trajectory for Earth without using the main engine to any significant degree. This is to ensure that if the ESM were to suffer a significant issue with its propulsion system, the crew can still be returned to Earth; only the vehicle’s reaction control system (RCS) thrusters will be required for mid-course corrections.

This also means that the mission will only make a single pass around the Moon, not enter orbit. It will pass over the Moon’s far side at a distance of some 10,300 kilometres and then head back to Earth. On approaching Earth, the Orion capsule will detach from the ESM, perform the revised re-entry flight to hopefully minimise any risk of spalling / char loss, prior to splashing down in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California.

I’ll have more on the actual mission and the flight itself as it takes place. In the meantime, my thanks to the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration (CDSE) for hosting a special webinair on Artemis 2 in December 2025, from which portions of this article – particularly some of the graphics – were drawn.