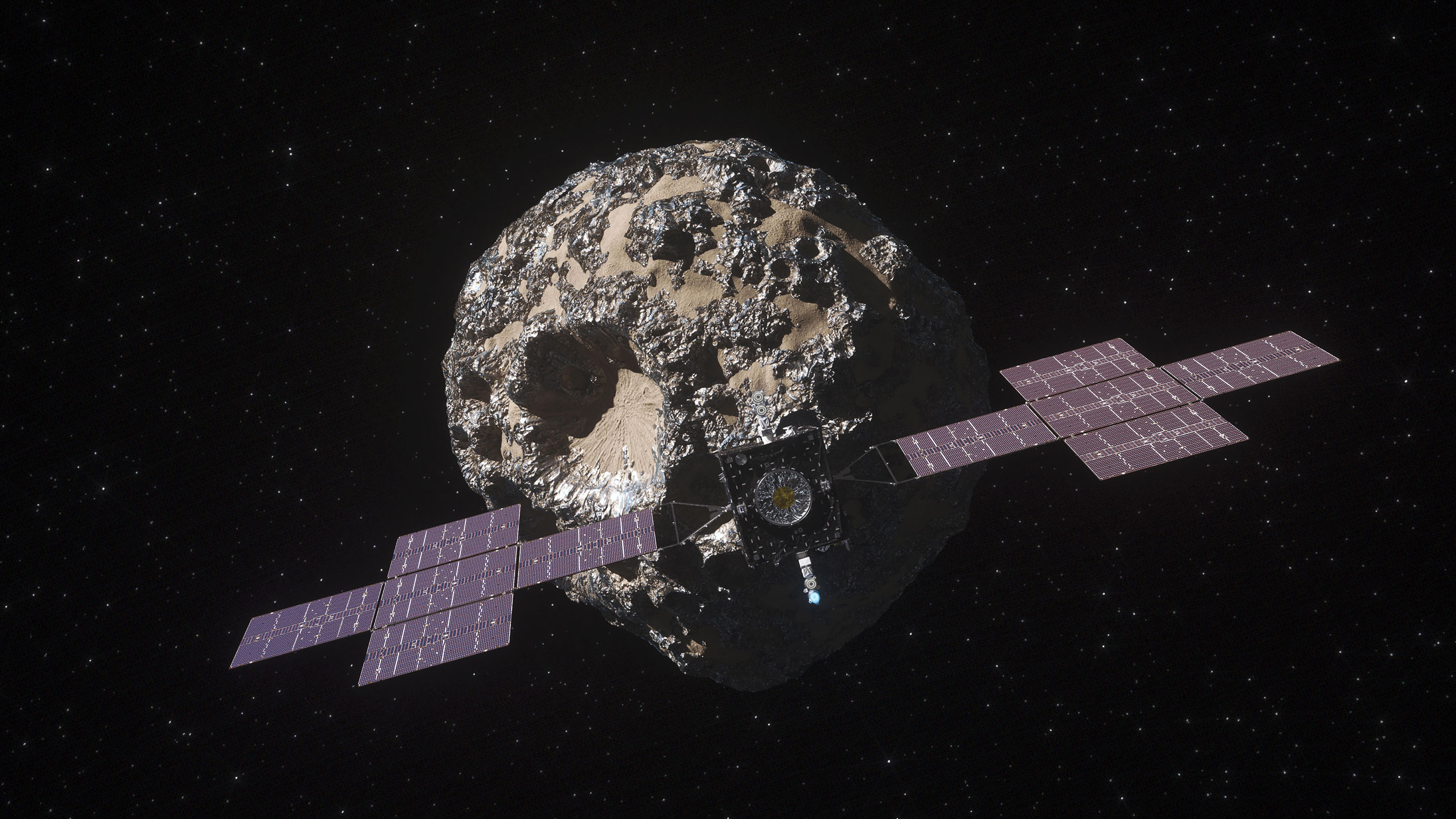

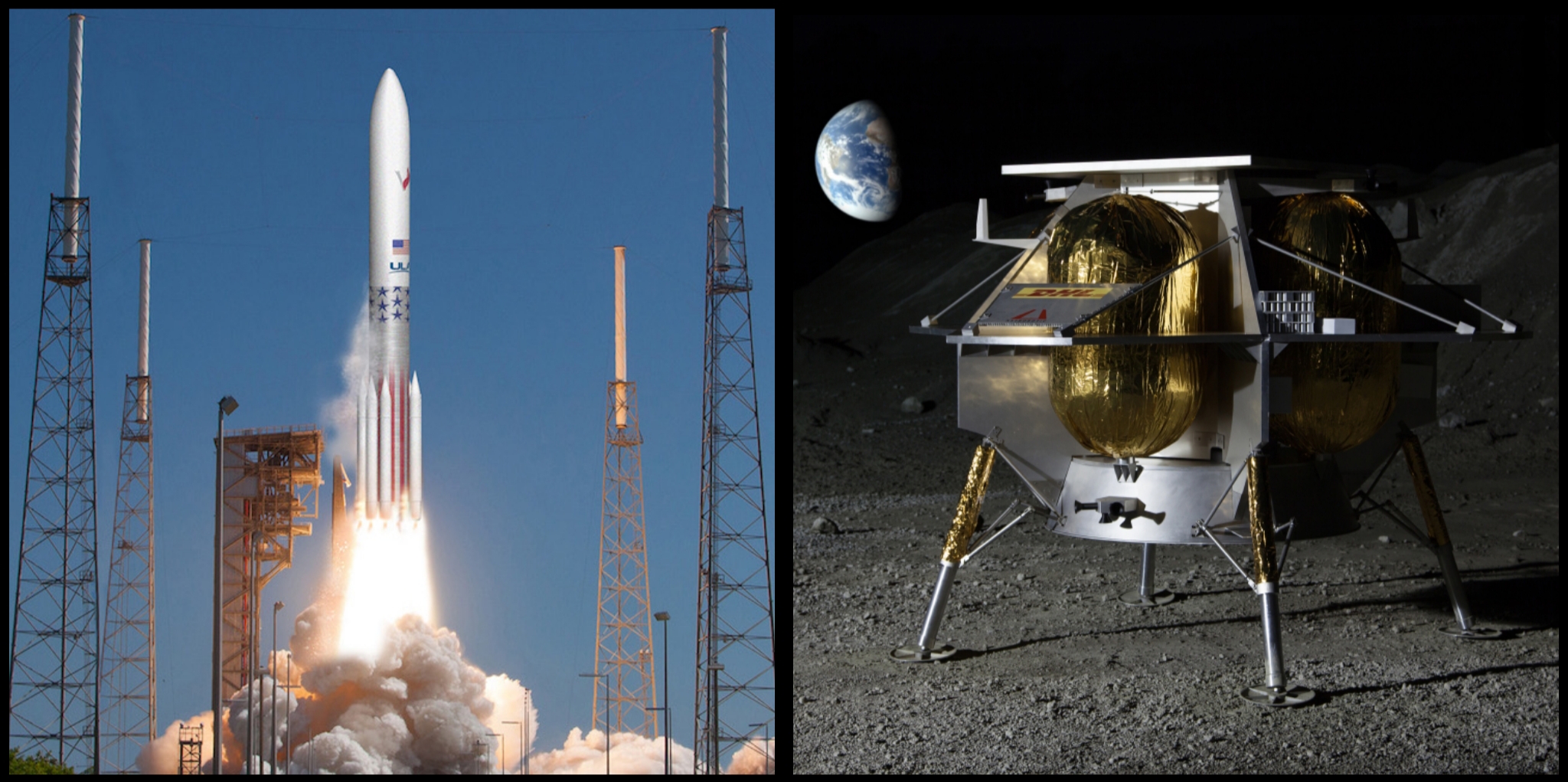

America’s return to the surface Moon as a part of government-funded activities will start in earnest over Christmas 2023, with the launch of the NASA-supported Peregrine Mission One and the Peregrine lander, built by Astrobotic Technology, which will take to the sky on December 24th, 2023 atop a Vulcan Centaur rocket out of Cape Canaveral Space Force Base, Florida.

Originally a private mission, Mission One qualified for NASA funding under the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) in 2018, effectively making it the first lander programme funded by NASA under the broader umbrella of the Artemis programme. In this capacity, the mission will fly 14 NASA-funded science payloads in addition to the original 14 private payloads planned for the mission.

The mission will be the inaugural payload carrying flight for the Vulcan Centaur, with the lander arriving in lunar orbit after just a few days flight – but will not land until January 25th, 2024, the delay due to the need to await the having to wait for the right lighting conditions at the landing site.

I’ll have more on this mission closer to the launch date, but in the meantime, as the Peregrine Mission One launch date is getting closer, the date for America’s return to the Moon with a crewed mission is slipping further away.

In terms of the Artemis crewed programmed, there have been a number of flags raised around the stated time-frame for Artemis 3, the mission slated to deliver the first such crew to the surface of the Moon in 2025, over the past few years. These have notably come from NASA’s own Office of Inspector General (OIG), but similar concerns have also started to be more openly voiced from within NASA.

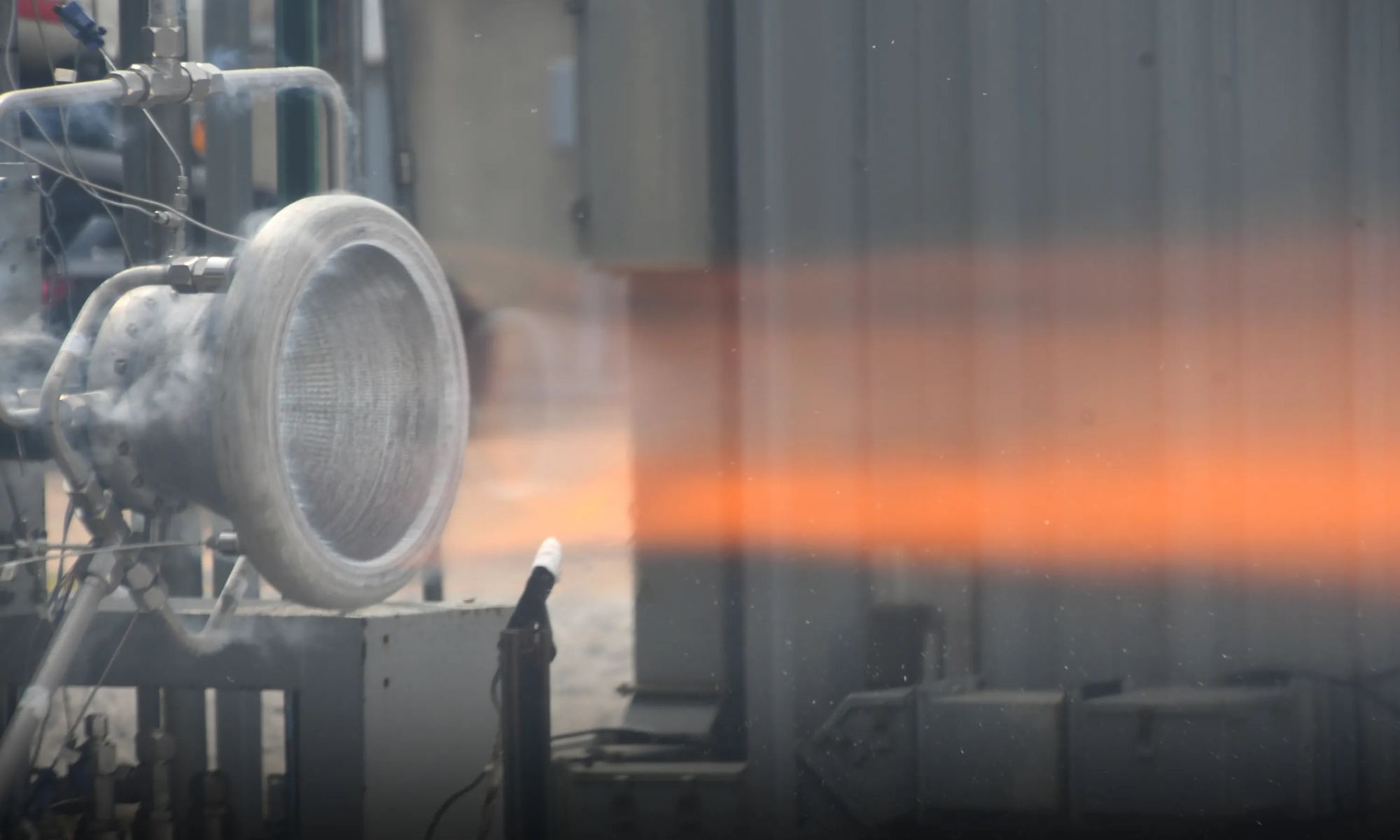

These concerns largely focus on whether or not SpaceX can provide NASA with its promised lunar lander and its supporting infrastructure in anything like a timely manner, given that SpaceX has yet to actually successfully fly a Starship vehicle. In this, the awarding of the lander vehicle – called the Human Landing System (HLS) in NASA parlance – to SpaceX, who propose using a specialised version of the Starship vehicle, was always controversial. For one thing, Starship HLS will be incapable of being launched directly to lunar orbit. Instead, it will have to initially go to low Earth orbit and reload itself with propellants – which will also have to be carried to orbit by other Starship vehicles.

At the time the contract for HLS was awarded (2021), competing bidders Blue Origin noted that according to SpaceX’s own data for Starship, a HLS variant of the vehicle would require the launch of fifteen other starship vehicles just to get it to the Moon. The first of these would be another modified Starship designed to be an “orbiting fuel depot”. It would then be followed by 14 further “tanker” Starship flights, which would transfer up to 100 tonnes of propellant per flight for transfer to the “fuel depot”. Only after these flights had been performed, would the Starship HLS be launched – and it would have to rendezvous with the “fuel depot” and transfer the majority of propellants (approx. 1,200 tonnes) from the depot to its own tanks in order to be able to boost itself to the Moon and then brake itself into lunar orbit.

Despite such claims being made on the basis of SpaceX’s own figures, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk pooh-poohed them, claiming all such refuelling could be done in around 4-8 flights, not 16. Despite their own OIG and the US Government Accountability Office (GOA) agreeing with the 16-flight estimation, NASA nevertheless opted to accept Musk’s claim of 4-8 launches, going so far is to use it in their own mission graphics.

However, the agency appeared to step back from this on November 17th, 2023, when Lakiesha Hawkins, assistant deputy associate administrator in NASA’s Moon to Mars Programme Office, confirmed that SpaceX will need “almost 20” Starship launches in order to get their HLS vehicle to the Moon, with launches at a relatively high cadence to avoid issues of boil-off occurring when storing propellant in orbit.

Now the US Government Accountability Office (GOA) has re-joined the debate, underlining the belief that SpaceX is far from being in any position to make good on its promises regarding the available of HLS. In particular the report highlights SpaceX is still a good way from demonstrating it can successfully orbit (and re-fly) a Starship vehicle, and it has not even started to demonstrate it has the means to store upwards of 1,000 tonnes of propellants in orbit, or the means by which volumes of propellants well above what has thus far been achieved can be safely and efficiently be transferred between space vehicles, and it has yet to produce a even a prototype design for the vehicle.

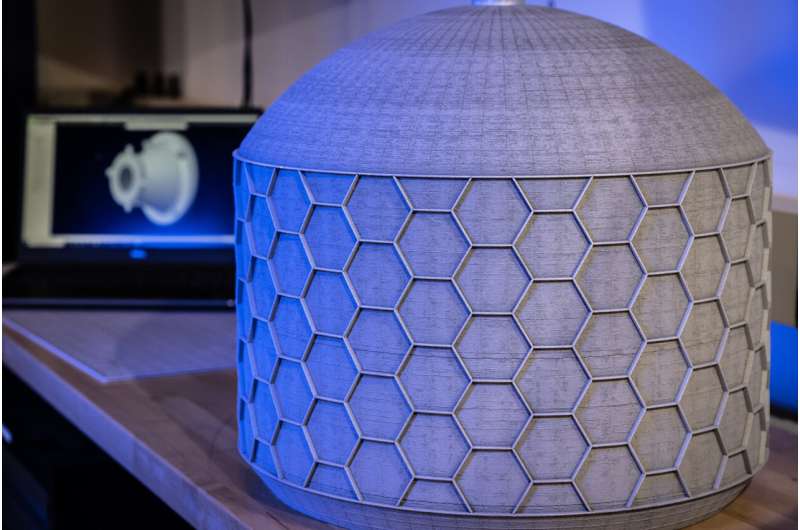

Nor does the report end there; it is also highly critical of the manner in which NASA has managed the equally important element of space suit design, firstly in awarding the initial contract for the Artemis lunar space suits to Axiom Space – a company with no practical experience in spacesuit design and development – rather than a company like ILC Dover, which has produced all of NASA’s space suits since Apollo; then secondly in failing to provide Axiom with all the criteria for the suits, necessitating Axiom redesigning various elements of their suit to meet safety / emergency life support needs.

As a result, the GAO concludes that it is likely Artemis 3 will be in a position to go ahead much before 2027; there is just too much to do and too much to successfully develop for the mission to go ahead any sooner. In this, there is a certain irony. When Artemis was originally roadmapped, it was for a first crewed landing in 2028; however, the entire programme was unduly accelerated in 2019 by the Trump Administration, which wanted the first crewed mission to take place no later than December 2024, so as to fall within what they believed would be their second term in office. Had NASA been able to stick with the original plan of 2028, there is a good chance that right now, it would be considered as being “on target”, rather than being seen as “failing” to meet time frames.

Hubble Hits Further Gyro Issues

On November 29th, 2023, NASA announced that the ageing Hubble Space Telescope (HST) had entered a “safe” mode for an indefinite period due to further troubles with the system of gyroscopes used to point the observatory and hold it steady during imaging.

In all, HST has six gyroscopes (comprising 3 pairs – a primary and a back-up),with one of each pair required for normal operations. To help increase the telescope’s operational life, all three pairs of gyros were replaced in the last shuttle mission to service Hubble in 2009, and software was uploaded to the observatory to allow it to function on two gyros – or even one (with greatly reduced science capacity) should it become necessary.

Today, only 3 of those gyros remain operational, the other three having simply worn out, and on November 19th, one of those remaining 3 started producing incorrect data, causing the telescope to enter a safe mode, stopping all science operations. Engineers investigating the issue were able to get the gyro operating correctly in short order, allowing Hubble to resume operations – only for the gyro to glitch again on November 21st and again on November 23rd, leading to the decision to leave the telescope in its safe mode until the issue can be more fully assessed.

The news of the problems immediately led to renewed calls for either a crewed servicing mission to Hubble or some form of automated servicing mission – either of which might also be used to boost HST’s declining orbit. However, such missions are far more easily said than done: currently, there isn’t any robotic craft capable of servicing Hubble (not the hardware or software to make one possible). When it comes to crewed missions, it needs to be remembered that Hubble was designed to be serviced by the space shuttle, which could carry a special adaptor in its cargo bay to which Hubble could be attached, providing a stable platform from which work could be conducted, with the shuttle’s robot arm also making a range of tasks possible, whilst the bulk of the shuttle itself made raising Hubble’s orbit much more straightforward.

Currently, the only US crewed vehicle capable of servicing HST is the SpaceX Crew Dragon – and it is far from ideal, having none of the advantages or capabilities offered by the space shuttle, despite the gung-ho attitude of many Space X supporters. In fact, it is not unfair to say that having such a vehicle free-flying in such close proximity to Hubble, together with astronauts floating around on tethers could do more harm than good.

A further issue with any servicing mission is that of financing. Right now, the money isn’t in the pot in terms of any funding NASA might make available for a servicing mission – and its science budget is liable to get a lot tighter in 2024, which could see Hubble’s overall budget cut.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: lunar delays and planetary dances”