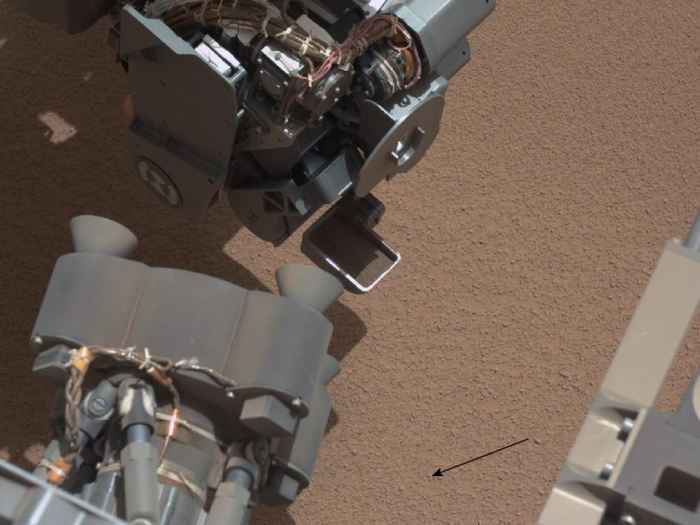

Curiosity is coming to the end of its time at Rocknest, the sandy area in Gale Crater where it has been sifting and examining soil samples and carrying out other experiments over the course of the last few weeks. Glenelg still remains the intended target for the rover, prior to it starting an exploration to the near-central mound in the crater NASA refer to as “Mount Sharp”.

Curiosity is coming to the end of its time at Rocknest, the sandy area in Gale Crater where it has been sifting and examining soil samples and carrying out other experiments over the course of the last few weeks. Glenelg still remains the intended target for the rover, prior to it starting an exploration to the near-central mound in the crater NASA refer to as “Mount Sharp”.

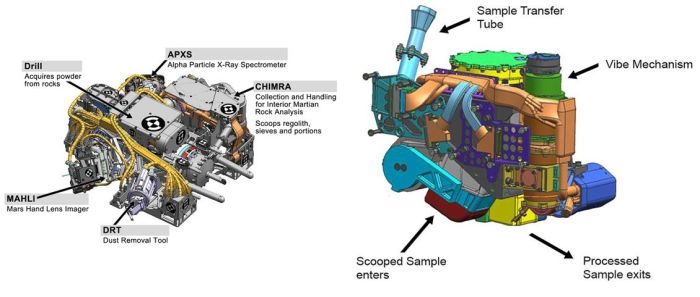

Since my last update on 31st October, Curiosity has been using the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument suite to examine the atmosphere in Gale Crate in greater detail. SAM is a remarkably flexible and complex set of instruments, able to analyse air and soil samples a number of ways.

Earlier in the mission, SAM was used to obtain an initial sampling of Martian air “inhaled” at Bradbury Landing. This was subjected to initial analysis by the instrument’s mass spectrometer. Over the last few days, Curiosity has used SAM to further sample the Martian Air, subjecting it to more detailed analysis using a Turnable Laser Spectrometer (TLS).

The TLS shoots laser beams into a measurement chamber which can be filled with Mars air. By measuring the absorption of light at specific wavelengths, the tool can measure concentrations of methane, carbon dioxide and water vapor in the Martian atmosphere and different isotopes of those gases.

Methane is of particular interest to scientists as, while it can be produced by either biological or non-biological processes, it is regarded as a simple precursor chemical for life. SAM represents the most sensitive tool yet deployed on or around Mars which might be capable of detecting methane in the atmosphere. However, the task isn’t easy, as it is probable that if the gas does exist at all within the Martian air, it is liable to do so only in very light traces. Certainly, none wer found in the initial sample analysed by Curiosity’s TLS, as SAM TLS lead Chris Webster of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) confirmed in a press conference I dialled-in to last week.

“Methane is clearly not an abundant gas at the Gale Crater site, if it is there at all. At this point in the mission we’re just excited to be searching for it,” he said. “While we determine upper limits on low values, atmospheric variability in the Martian atmosphere could yet hold surprises for us.”

Please use the page numbers below to continue reading this article