In the world of commercial space development, there is a tendency to pooh-pooh the efforts of Blue Origin, the company founded by billionaire Jeff Bezos. This is chiefly done through comparisons with SpaceX, a company which has achieved a lot over the last decade in particular, albeit (and contrary to what SpaceX fans will insist as being the case) largely at the largesse of the US government, from whom the company receives the lion’s share of its revenue.

However, this may all be about to change. Whilst much of the public focus on Blue Origin has been on their sub-orbital New Shepard vehicle catering to the space tourism industry, the company is now gearing-up in earnest for the (somewhat overdue) launch of its massive New Glenn launch system.

Originally targeting a maiden flight in 2020, the 98-metre tall vehicle is now due to launch in November 2024 from Cape Canaveral Space Launch Complex 36. The payload for this mission was to have been NASA’s Mars EscaPADE mission. However, that mission was removed from the flight by NASA over concerns that Blue Origin might miss the required launch window. As a result, the company switched its attention to the second planned flight for New Glenn, a demonstration flight for the United States Space Force’s National Security Space Launch (NSSL) programme, with the payload taking the form of a prototype of Blue Origin’s Blue Ring spacecraft platform.

New Glenn is classified as a heavy lift launch vehicle with a maximum payload capacity to low-Earth Orbit (LEO) of 45 tonnes, with a fully reusable first stage. This compares favourably with Falcon Heavy’s 50 tonnes with all three of its core stages recoverable (although the latter can lift up to 63 tonnes to LEO when all three core stages are discarded). In addition, New Glenn is designed to deliver up to 13.6 tonne to geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) and up to 7 tonnes to the Moon, as well as the ability to send payloads deeper into the solar system.

As well as the first stage of the rocket being designed from the ground up to be reusable, Blue Origin plan to replace the current expendable upper stage of the system with a reusable stage called Jarvis; however, little has been heard on this front since 2021. If it happens, it will make New Glenn fully reusable.

In September 2024, the company carried out static fire tests of the expendable upper stage of the rocket, and on October 30th, Blue Origin rolled-out the first stage for the maiden launch from its Exploration Park complex at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station for a 37 km, multi-hour road trip to Launch Complex 36 “having to go the long way round” as Dave Limp, Blue Origin’s CEO put it.

The long journey was the result of the sheer size of the booster and its transporter: a 94.5 metre long behemoth comprising a powerful tractor and two trailers with a total of 22 axles and 176 tyres. Simply put, it’s not the most manoeuvrable transport, with or without a 57.5 metre first stage on its back; as such, the route from factory facility to pad had to reflect this.

The stage in question comprised an engine module which also includes the landing legs, the core tank section and am upper interconnect – the section of a booster onto which the upper stage connects. After being delivered to the vehicle integration facility at SLC-36, Limp confirmed it will be participating in an integrated hot-fire test.

Each New Glenn first stage is designed to be re-used 25 times, with Blue Origin planning a cadence of up to 8 launches per year, and already have a growing list of customers. While this cadence might not sound as extensive as SpaceX and Falcon 9, it should be remembered that the larger percentage of SpaceX Falcon 9 launches are non-commercial / non-government / non-revenue generating Starlink launches; as such, New Glenn’s cadence is potentially in step with the current state of the US commercial and government launch requirements.

As noted, for the inaugural launch, New Glenn will be carrying a prototype Blue Ring satellite platform capable of delivering up to 3 tonnes of payload to different orbits, and capable of on-orbit satellite refuelling (as well as being refuelled in orbit itself) and transporting them between orbits, if required. It is “launch vehicle agnostic”, meaning it can be flown with payloads aboard any suitable vehicle – New Glenn, Vulcan Centaur, Falcon 9.

The prototype will be flown as the Dark Sky-1 (DS-1) mission, intended to demonstrate the vehicle’s Blue Origin’s flight systems, including space-based processing capabilities, telemetry, tracking and command (TT&C) hardware, and ground-based radiometric tracking in order to prove the craft’s operational capabilities in both commercial and military uses. To achieve this, the vehicle will operation in a medium Earth orbit (MEO), ranging between 2,400 km by 19,300 km.

In addition, the flight will be used to check the New Glenn upper stage’s ability to re-light its motors multiple times. After the launch, the first stage will attempt to make a return to Earth and a landing at sea aboard the company’s Landing Platform Vessel 1 (LPV-1) Jacklyn, as shown in the video below.

The company is targeting the end of November for New Glenn’s inaugural launch. However, given the work still to be completed, it is possible this might slip to December 2024. If successful, the flight will for one of two certification launches for the USSF NSSL programme, both of which are required to clear New Glenn for classified lunches.

As well as these projects – all of which have been directly funded by Bezos himself outside of a modest contract payment made under a Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) payment – Blue Origin is well on the way to developing its Blue Moon Mark 2 lunar lander, capable of supporting up to four astronauts on the surface of the Moon for up to 30 days.

A cargo variant of the lander, able to deliver between 20 and 30 tonnes (non-reusable) to the lunar surface is also in development. Both versions are intended to be part of NASA’s sustainable lunar architecture to follow the use of the SpaceX HLS vehicle (Artemis 3 and 4). However, there is some speculation that Blue Moon – due to be used with Artemis 5 onwards – is much further along in its development that the SpaceX HLS, and Artemis 5 might fly in the slot in Artemis 3 mission. Time will tell on this as well.

Voyager 1: Communications Issues

I’ve covered the Voyager mission, and its twin spacecraft Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 numerous times in these pages. After 47 years, both craft are now operating beyond the heliopause, and whilst technically still within the “greater solar system” and heading for the theorised Oort Cloud, both craft are now operating in the interstellar medium. However, they are obviously aging, and this is impacting their ability to operate.

As I recently reported, as a result of both vehicles’ declining ability to generate electrical power, NASA has, since 1998, been slowing turning off their science instruments in the hope that they can eke out sufficient electrical power from the RTGs powering both craft to allow them to continue to operate in some capacity into the early 2030s. However, this is far from a given, as again demonstrated in October 2024.

As a part of the “power saving” activities with both Voyager craft, mission engineers periodically power down one of vehicles’ on-board heaters, reducing the electrical load on the RTGs, and then ordering the heater to power-back up as and then powering-down another. On October 16th, 2024, a command was sent to Voyager 1 to power-up one such heater. Due to the distances involved, confirmation that the command had been received and executed would not be received for almost 48 hours. However, on October 18th, NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN), responsible for (among other things) communicating with all of NASA’s robotic missions, reported it was no longer receiving Voyager 1’s “heartbeat ping” periodically sent from the vehicle to Earth to confirm it was still in communications.

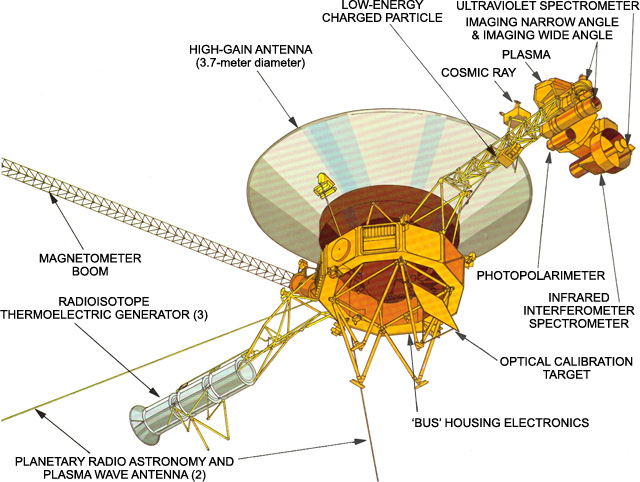

Both Voyager craft have two primary communications systems: a high-power X- band (8.0–12.0 GHz frequency) for downlink communications from the craft to Earth and a less power-intensive S-band (2 to 4 GHz frequency) for uplink communications from Earth to the craft. However, each also has a back-up S-band capability for downlink communications, but because it is of a lower power output than the X-band, it hasn’t been used since around 1981.

Realising the loss of X-band communications had effectively come on top of the command to turn on a heater, engineers theorised that in trying to power on the heater, Voyager 1 had exceeded its available power budget and entered a “safe” mode, turning off the power-hungry X-band communications system to provide power to the heater. They then trained over to the much lower-power S-band downlink frequency, as any loss of the X-band system should have triggered an automatic switch-over – and sure enough, after a while, Voyager 1’s “heartbeat ping” was received.

This allowed a test to be carried out in sending and receiving commands and responses entirely via S-band, and on October 24th, NASA confirmed communications with the vehicle had been re-established. The work of diagnosing precisely what triggered the “safe” mode & shut down of the X-band system is now in progress, and the latter communications system will remain turned off until engineers are reasonably confident that re-activating it will not trigger a further “safe” mode response.

NASA Confirms Root of Orion Heat Shield Issues – But Won’t (Yet) Disclose

There are, frankly, multiple issues with the US-led Artemis Project to return humans to the surface of the Moon by 2030. They encapsulate everything from the vehicles to be used to reach the Moon and its surface (NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and the SpaceX Human Landing System and its over-the-top mission complexity of anywhere between 10 and 16 launches just to get it to lunar orbit) the supporting Lunar Gateway space station and its value / cost, etc. However, from a crew perspective, one of the most troubling had been with the heat shield used on the Orion vehicle – the craft intended to carry crews to cislunar space and, most particularly, return them to Earth.

Orion has thus far made one, unscrewed, flight to the Moon and back, in November / December 2022 (see here and here for more). While the system as a whole – capsule and service module – operated near-flawlessly, with the capsule making a successful return to Earth and a splashdown on December 11th, 2022, post-flight examination revealed that the craft’s heat shield had suffered a lot more damage – referred to as “char loss” – that had been anticipated.

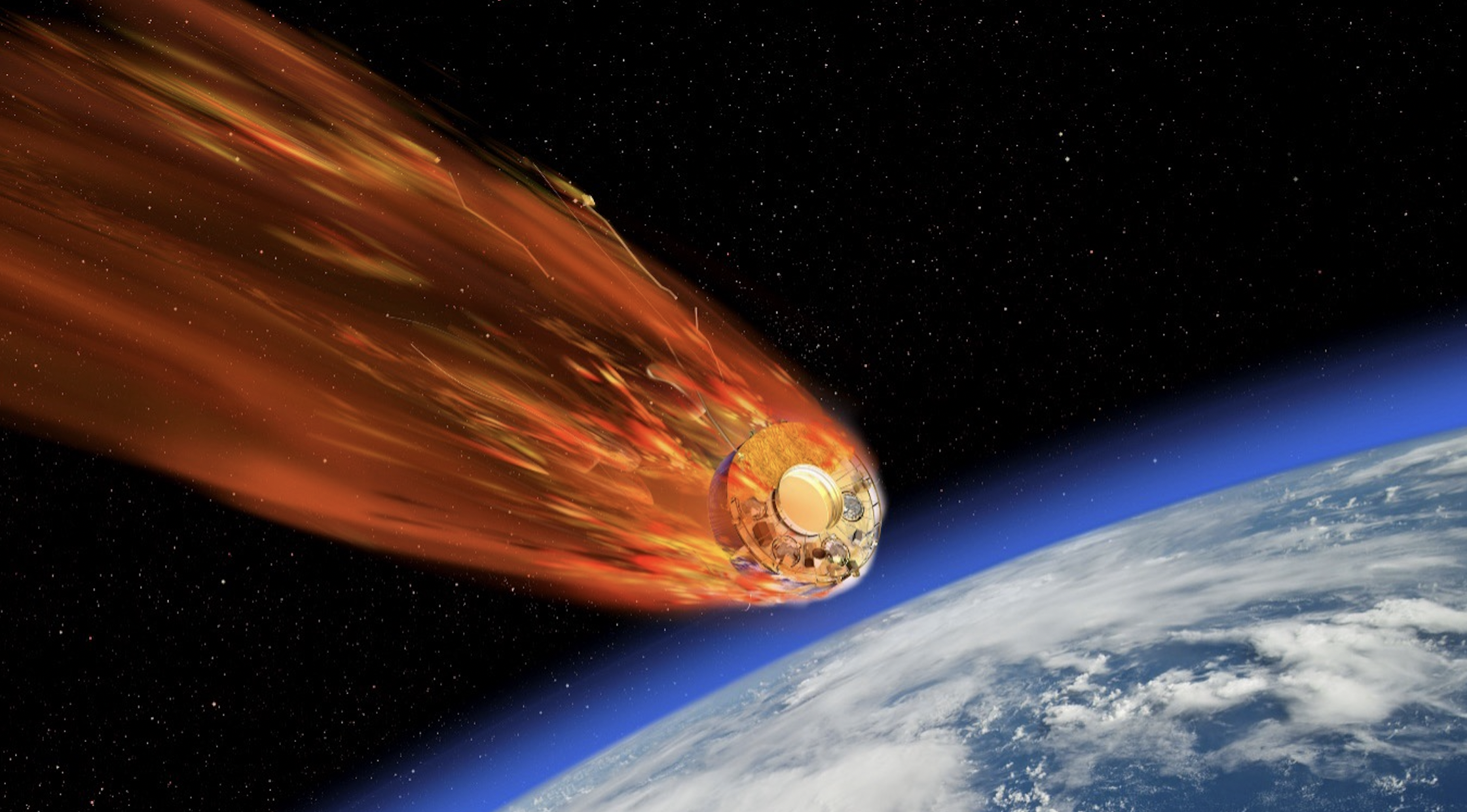

As with most capsule systems, Orion uses an ablative heat shield which is designed to carry away heat generated during re-entry into the atmosphere through the twin process of melting and ablating to dissipate the initial thermal load, and pyrolysis to produce gases which are effectively “blown” over the surface of the heat shield to form a boundary layer between the heat shield and the plasma generated by the frictional heat of the capsule’s passage into the denser atmosphere, producing a “thermal buffer” again the heat reaching the vehicle.

Ablative materials do not necessarily melt / ablate (the “char loss” process) evenly and can lead to gouges and strakes in the surviving heat shield. However, this is not what happened with the heat shield used in the Artemis 1 mission. Rather than melting and ablating, the heat shield material, known as Avcoat, appeared to crack and break away in chunks, creating a visible debris trail behind the craft during re-entry and leaving the heat shield itself pock-marked with holes and breaks looking like someone had taken a hammer to it.

While the damage was not severe enough to put the capsule itself at risk, it was clearly of concern as it indicated a potential for some form of burn-through to occur in a future flight and put vehicle and crew at risk of loss. NASA and its contractors have therefore been seeking to understand what happened as Artemis 1 Orion capsule was re-entering the atmosphere, and what needs to be done to avoid such deep pitting and damage in future missions.

Most of this work has been carried out well away from the public eye; in fact, the only images of the damage caused to the heat shield were published as part of a report produced by NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) in May 2024.

On October 24th, 2024 NASA indicated, by way of two separate statements, that they now understand what caused to Artemis 1 heat shield to ablate as it did, and know what needs to be done to prevent the problem with missions from Artemis 3 onwards. However, the agency has said it will not disclose the problem or its resolution, as they are still investigating what needs to be done with the Artemis 2 heat shield.

We have conclusive determination of what the root cause is of the issue. We have been able to demonstrate and reproduce it in the arc jet facilities out at Ames. We know what needs to be done for future missions, but the Artemis 2 heat shield is already built, so how do we assure astronaut safety with Artemis 2?

– Lori Glaze, acting deputy associate administrator, NASA Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate

Artemis 2 was slated for a 2024 launch, but was pushed back to no earlier than September 2025 in order to allow time for the heat shield investigations, and for the upgrade of various electronics in the Orion capsule’s life support systems. Glaze’s comments suggest that NASA might have to completely replace the heat shield currently part of the Orion capsule slated to be used in the Artemis 2 flight. If this is the case, then it could potentially further delay the launch.