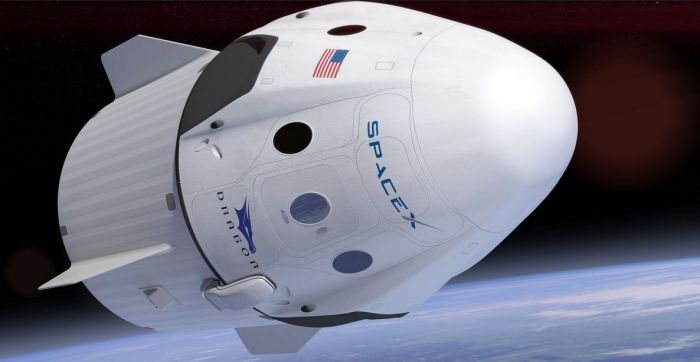

While most private space tourism companies are busily going about various routes to offer sub-orbital flights to those who can afford them, Elon Musk’s SpaceX has stepped into the arena – and, as might be expected, made the bold announcement it will go one better: fly paying passengers around the Moon and back. And they plan to do it in 2018.

The announcement was made by Musk on Monday, February 27th during a press teleconference. If the flight goes ahead, it will allow two fare-paying passengers the opportunity to undertake a week-long journey out to and around the Moon, before returning to Earth. The flight would use a “free return” profile which would see it skim over the surface of the Moon and continue outward beyond it, possibly as far as 480,000 Km (300,000 mi) from the Earth (the average distance of the Moon from Earth is around 384,400km / 240,000 mi), before Lunar gravity takes over and hauls the vehicle back towards the Earth, where it would splash down.

It’s not clear how much the passengers would pay to be on the flight – but the going price for a seat aboard the Dragon 2 vehicle, which would be used for the flight, will be around US $58 million a pop to get to the International Space Station, once it enters service. It’s also far from clear if SpaceX can actually deliver on the goal of launching the flight in late 2018.

In order to take place, the flight first and foremost needs a launch vehicle and a suitable space vehicle. SpaceX plan to use their mighty Falcon Heavy and – as noted – their new Dragon 2 crewed vehicle. There’s just a couple of problems with both.

The Falcon Heavy is not due to fly until some time later in 2017, and even then it will not be rated for crewed launches. For that to happen, it will have to be certified for crew use, and depending on how the initial flights go, that could take time. In terms of the Dragon 2, that is not scheduled to enter service until 2018 – and even then, its primary function is to fly crews to and from the International Space Station (ISS).

Ferry flights to the ISS are vastly different to going out around the Moon and back. To start with, the outward flight from Earth to the ISS can be measured in just a couple of days – around a quarter of the time needed for the lunar trip. The velocity (delta vee) imparted to a spacecraft going to the ISS (28,000 km/h / 17,500 mph) is also a lot less than required to go to the Moon (40,000 km/h / 25,000 mph).

This means a returning Dragon 2 will be re-entering the Earth atmosphere a lot faster than the same craft coming back from the ISS, and will have to face much higher re-entry temperatures and a harsher deceleration regime. While the Dragon 2 can in theory do so, it is likely that significant testing on uncrewed vehicles will be required before the Federal Aviation Authority and NASA agree to any such flight taking place. On top of this, it will have to be demonstrated that the Dragon 2 can be outfitted for a deep space mission and keep a crew alive and well for around 7-8 days.

Given all this, there are widespread doubts the company can meet a 2018 deadline for such a mission – and SpaceX has tended to be ambitious with its time frames for achieve goals. They had originally slated 2013 as the year in which the Falcon Heavy would make its first flight – although in fairness, setbacks following the loss of two Falcon 9 vehicles also contributed to its launch being pushed back to 2017.

Red Dragon Delayed

As further evidence of SpaceX presenting time frames which are perhaps a little ambitious, on February 17th, the company announced its mission to land a variant of the Dragon 2 – dubbed Red Dragon – on Mars has been pushed back from 218 to 2020.

The aim of the mission so to fly an uncrewed 10-tonne Dragon 2 vehicle to Mars and land it safely. In doing so, the company hopes to gain valuable data on landing exceptionally heavy vehicles on Mars using purely propulsive means. This is because crewed landing vehicles on a Mars mission are liable to have a mass of at least 40 tonnes – far too much to be safely slowed in a descent through the thin Martian atmosphere by parachutes.

The planned mission would be undertaken entirely at the company’s own expense, although it would can science instruments and experiments supplied by NASA. For Musk it, and possibly three further Red Dragon mission which could follow it in the 2020-2024 time frame, is a vital precursor to greater ambitions for Mars.

As he outlined in September 2016 (see: Musk on Mars), Musk plans to start launching crewed missions to Mars, possibly before 2030. The initial missions will doubtless be modest in size in terms of crew and goals. However, his overall stated goal is to kick-start the colonisation of Mars. To do that, he plans to use vehicles massing at least 100 tonnes and which can make a propulsive landing on Mars. Whether he can succeed in even the step to land a crew on Mars – and bring them back to Earth – remains to be seen. However, his Red Dragon mission is an important first step.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: Moon flights and the winds of Mars”