The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) successfully launched its Chandrayaan-2 mission to the lunar south pole on Monday, July 22nd, after suffering a week’s day to the schedule. This is an ambitious mission that aims to be the first to land in the Moon’s South Polar region, comprising three parts: an orbiter, a lander and a rover.

Although launched atop India’s most powerful rocket, the GSLV Mk III, the mass of the mission means it cannot take a direct route to Mars, as the upper stage isn’t powerful enough for the mass. Instead, Chandrayaan-2 was placed into an extended 170km x 39,120 km (105 mi x 24,300 mi) elliptical orbit around the earth. For the next month, the orbiter will gradually raise this obit until it reaches a point where lunar gravity becomes dominant, allowing Chandrayaan-2 to transfer into a similarly extended lunar orbit before easing its way down to a 100 km (60 mi) circular polar orbit around the Moon, which it is scheduled to achieve seen days after translating into its initial lunar orbit.

During this period, the combined vehicle will carry out multiple surveys of the Moon’s survey, focusing on the South Pole. It will also release the 1.47-tonne Vikram lander (named for Vikram Sarabhai, regarded as the father of the Indian space programme) which will make a soft decent to the lunar surface, which will take several days prior to making a soft landing.

The orbiter vehicle is designed to operate for a year in its polar orbit for one year. It carries a science suite of eight systems, including the Terrain Mapping Camera (TMC), which will produce a 3D map for studying lunar mineralogy and geology, an X-ray spectrometer, solar X-ray monitor, imaging spectrometer and a high-resolution camera.

The Vikram lander, with four science payloads, will communicate both directly with Earth and the orbiter. It will also facilitate communications with the Pragyan rover, which will be deployed within hours of the self-guiding lander touching down. Between them, the lander and rover carry 5 further science experiments and both are expected to operate for around 14 days.

Craters in the South Polar region lie in permanent shadow and experience some of the coldest temperatures in the solar system and NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has revealed they contain frozen water within them, water likely unchanged since the early days of the Solar System, and thus could hold clues to the history of the Solar System – hence the interest in visiting the region and learning more. The frozen water is also of interest to engineers as it could be extracted to provide water for lunar base; water that could be used for drinking, or growing plants and could also me split to produce oxygen and hydrogen – essential fuel stocks.

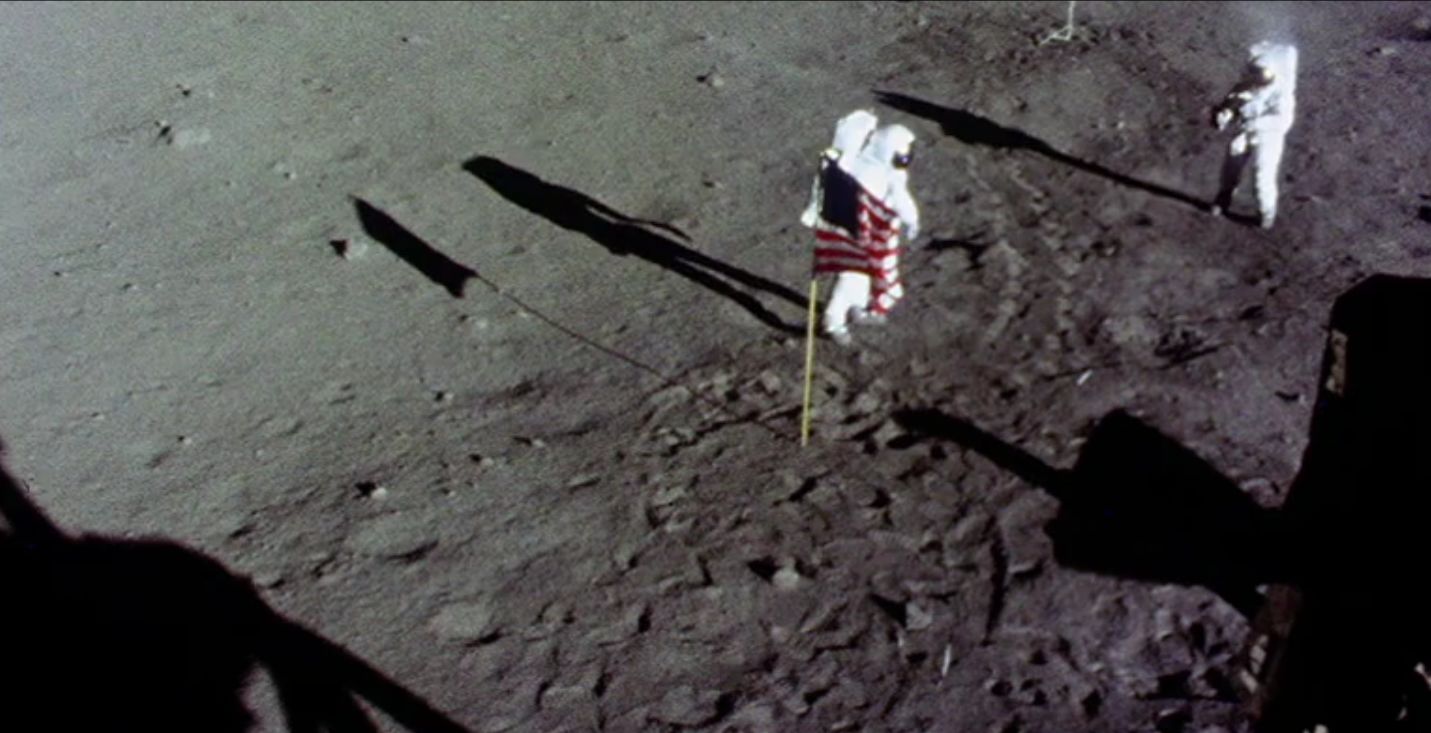

The Chandrayaan-2 mission marks a significant step forward for India’s space ambitions; assuming the Vikram lander is successful, the country will become only the forth nation to land on the Moon after the United States, Russia and China. As a part of its expanding activities in space, the country hopes to fly it first astronauts into space in 2022 and have an operational space station by the end of the 2020s.

2019 OK

No, I’m not making a statement about the year – that’s the name of a chunk of space rock measuring 57 to 130m (187 to 42ft) across that passed by Earth at a distance of around 73,000 km (45,000 mi), putting it “uncomfortably close” to the planet. What’s more, we barely released it was there: 2019 OK was positively identified by the Southern Observatory for Near Earth Asteroids Research (SONEAR), just a couple of days prior to is passage past Earth, and was confirmed by the ASAS-SN telescope network in Ohio, leaving just hours for an announcement of its passage to be made.

Since then, the asteroid’s orbit has been tracked – forward and back (which revealed it had been previously spotted by observatories, but its small size and low magnitude meant its significance wasn’t realised). These observations confirmed 2019 OK is a reactively short-period object, orbiting the Sun every 2.7 years. It passes well beyond Mars before swinging back in and round the Sun, crossing the Earth’s orbit as it does so. However, while it may pass close to Earth on occasion, it’s highly unlikely it will ever strike us.

It does, however, remind us that near-Earth objects (NEOs) are common enough to be of concern; 2,000 were added to the list 2017 alone. The size of 2019 OK reminds us that there are more than enough of them to be of a significant enough size to pose a genuine threat.

In 2013, an asteroid measuring just 20m across entered the atmosphere to be ripped apart at an altitude of around 30 km above the Russian town of Chelyabinsk. The resultant resulting shock wave shattered glass down below and injured more than 1,000 people. 2019 OK is at a minimum 2.5 times larger than the Chelyabinsk object – and possibly as much as 10 times larger, putting it in the same class of object that caused the Tunguska event of 1908, when 2,000 sq km (770 sq mi) of Siberian forest was flattened by an air blast of 30 megatons as a result of a comet fragment breaking up in the atmosphere.

Hence why observatories such as SONEAR, ASAS-SN telescope network, the Catalina Sky Survey, Pan-STARRS, and ATLAS and others attempt to track and catalogue NEOs. The more of them we can located and establish their orbits, the more clearly we can identify real threats – and have (hopefully) a lead time long enough to take action against them.

Oh, and if you thought 2019 OK was big, consider 99942 Apophis. It’s around 400-450m across, and will swing by Earth at a distance of just 31,000 km on – wait for it – Friday, April 13th, 2029 (so get ready for a lot of apocalyptic predictions in the months leading up to that date!).

Continue reading “Space Sunday: lunar landers, asteroids and more”