NASA has announced that Artemis 2 – the first mission of the programme to send a crew to cislunar space – is now targeting a launch for the period between February 5th, 2026 and the end of April 2026.

The 10-day mission will carry a crew of four – three Americans and one Canadian – to the vicinity of the Moon and then back to Earth aboard an Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) in what will be the final test of that vehicle and its systems, together with the second flight of NASA’s Block 1 Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. The latter – SLS – is currently undergoing the final steps in its assembly process. Earlier this year the core and upper stages of the rocket were stacked at Kennedy Space Centre’s Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), where the two solid rocket boosters also stacked within the VAB were then attached to either side of the rocket’s core stage.

Meanwhile, and as I noted in August 2025, the Orion vehicle for the mission, together with its European-built Service Module, moved from NASA’s Multi-Payload Processing Facility (MPPF) to the Launch Abort System Facility (LASF), where it is being mated with its launch abort system tower. Once completed, the combination of Orion and launch abort system will be transferred to the VAB for installation on the SLS vehicle.

To this end, at the end of September 2025, NASA integrated the Artemis 2 Orion Stage Adapter with the rest of the SLS system. As its name suggests, the Orion Stage Adapter is the element required to mate Orion to the launch vehicle. In addition, the adapter will be used to deploy four CubeSats containing science and technology experiments into a high Earth orbit after Orion has separated from the SLS upper stage and is en route to the Moon.

Also at the end of September, the four crew due to fly the mission – Reid Wiseman (mission commander), Victor Glover, and Christina Koch all from NASA, and Canada’s Jeremy Hansen – revealed the name they had chosen for their Orion capsule: Integrity.

A couple months ago, we thought, as a crew, we need to name this spacecraft. We need to have a name for the Orion spacecraft that we’re going to ride this magical mission on. And so we got the four of us together and our backups, Jenny Gibbons from the Canadian Space Agency and Andre Douglas from NASA, and we went over to the quarantine facility here, and we basically locked ourselves in there until we came up with a name.

– Artemis 2 mission commander, Reid Wiseman

Integrity will be the second Orion capsule to join NASA’s operational fleet, the first being the still unnamed craft flown during the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission in 2022. That mission revealed an issue with the initial design of the vehicle’s re-entry heat shield, which received more and deeper damage than had been anticipated (see: Space Sunday: New Glenn, Voyager and Orion). This delayed Artemis 2 in order for investigations into the cause to take place and solutions determined.

In short: a return from the Moon involves far higher velocities than a return from Earth orbit (entering the atmosphere at 40,000 km/h compared to 28,000 km/h), resulting in far higher temperatures being experienced as the atmosphere around the vehicle is super-heated by the friction of the vehicle’s passage through it, further leading to increased ablation of the heat shield. This could be offset by using a very substantial and heavy heat shield, but as Orion is also intended to be launched on vehicles other than SLS and for other purposes (e.g. just flying to / from low Earth orbit), it is somewhat mass-critical and in need of a more lightweight heat shield.

As a result, rather than making a single plunge back into Earth’s atmosphere at the end of lunar missions, Orion was supposed to perform a series of initial “skips” or “dips” in and out of the denser atmosphere. These would allow the vehicle bleed-off velocity ahead of a “full” re-entry whilst also reducing the amount of plasma heating to which the ablative material of the heat shield would be exposed.

However, post-flight analysis of the heat shield used in the Artemis 1 mission of 2022, it was found that the heat shield had suffered extensive and worryingly deep material loss – referred to as “char loss”, resulting in a series of deep pits within the heat shield. Investigation revealed the cause of this being the initial “skips” the vehicle made into and out of the denser atmosphere.

While these “skips” did indeed reduce the load on the outer layers of the heat shield, they also had the unintended impact of heating-up gases trapped inside the ablative layers of the heat shield during its construction, causing the underlying layer of the material in the heat shield to expand and contract and start to crack and break. They, when the capsule entered its final plunge through the atmosphere prior to splashdown, the material over these damaged areas ablated away as intended, exposing the damaged material, which then quickly broke-up to leave the pits and holes.

To mitigate this, Artemis 3 and 4 will fly with a redesigned heat shield attached to their Orion capsules. However, Artemis 2 will fly with the same design as used in Artemis 1, but its re-entry profile has been substantially altered so it will carry out fewer “skips” in and out of the atmosphere before the final entry, and will do so at angles that will reduce the amount of internal heating within the heat shield layers.

Ahead of its launch, the complete Artemis 2 launch vehicle and payload should be rolled-out from the VAB to the launch pad early in 2026. It will then go through a series of pre-flight demonstration tests, up to and including a full “wet dress rehearsal”, wherein the rocket will be fully fuelled with propellants and go through a full countdown and lunch operation, stopping just short of actually igniting the engines. These test will then clear the way for the crewed launch.

Flying over Mars with Mars Express

When it comes to exploring Mars, NASA understandably tends to get the lion’s share of attention, simply by volume of its operational missions on and around the Red Planet. However, they are far from alone; Mars is very much an international destination, so to speak. One of the longest continuous missions to operate around Mars, for example, is Europe’s Mars Express mission, an orbiter which has been studying Mars for more than 22 years, marking it as the second-longest running such mission after NASA’s Mars Odyssey mission (now in its 24th year since launch).

During its time in orbit, Mars Express has provided the most complete map of the Martian atmosphere and its chemical composition currently available; produced thousands of high-definition images of the planet’s surface, revealing many of its unique features whilst also helping scientists understand the role of liquid water in the formation of the ancient Martian landscape; acted as a communications relay between other Mars missions and Earth, and it has even studied the innermost of Mars’ two captive moons, Phobos.

It is through the high-definition images returned by the orbiter that ESA has at times promoted the mission to the general public, notably through the release of galleries of images and the production of detailed “flyover” videos of the planet, revealing its unique terrain to audiences through the likes of You Tube. At the start of October 2025, ESA released the latest of these movies featuring the remarkable Xanthe Terra (“golden-yellow land”). Located just north of the Martian equator and to the south of Chryse Planitia where Viking Lander 1 touched-down on July 20th, 1976, and a place noted for its many indications that water played a major role in its formation.

The images used in the film were gathered using the orbiter’s High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) during a single orbit of the planet. Following their transmission to Earth, these were combined with topography data gathered in the same pass to create a three-dimensional view of a part of the region centred on Shalbatana Vallis, a 1300 km-long outflow channel running from the southern highlands into the northern lowlands on the edge of Chryse Planitia. The film also includes passage over Da Vinci crater. Some 100 km across, this crater is intriguing as it contains a smaller, more recent impact crater within it, complete with debris field.

Uranian Moon Ariel the Latest Moon to have an Ocean?

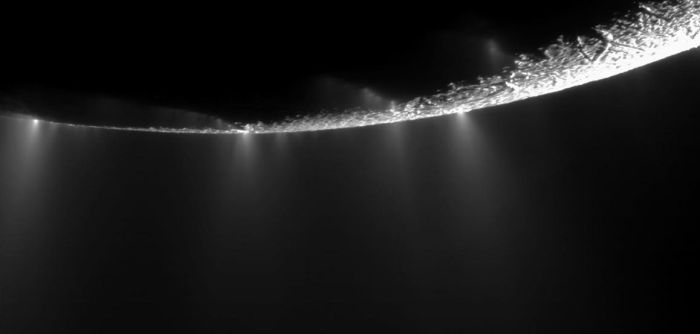

Jupiter’s Galilean moons of Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, together with Saturn’s Enceladus and Titan are all thought to have (or had) oceans of icy slush or liquid water under their surfaces. In the case of the Galilean moons, the evidence is so strong, Both NASA and ESA are currently sending probes to Jupiter to study them and their interiors. Similarly, the evidence for Enceladus – as I’ve covered numerous times in these pages – having a liquid water ocean under its ice is so powerful that calls for a mission to visit it are equally as strong.

Now Uranus is getting in on the act of having moons with what could be (or could have been) liquid water oceans under their surfaces, the latest contender being Ariel, the planet’s fourth largest and second closest of Uranus’s moons in hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e. largely globular in shape) to the planet, after Miranda.

Measuring just 1,160 km in diameter, Ariel is a comparatively tiny moon and not too much is known about it, other than it its density suggests it is made up of a mix of rock and ice, with a lean towards the latter. It orbits and rotates in Uranus’s equatorial plane, which is almost perpendicular to the planet’s orbit, giving the moon an extreme seasonal cycle. But the most remarkable aspect of Ariel is its extreme mix of geological structures: massive surface fractures, ridges and grabens – part of the moon’s crust that have dropped lower than its surroundings—at scales larger than almost anywhere else in the solar system.

Only one space mission has come close to visiting Ariel. NASA’s Voyager 2 zipped by the moon in 1986 at a distance of 127,000 km. This allowed the probe’s camera system to gather images of around 35% of the moon’s surface that were of sufficient spatial resolution (approx. 2 km) so as to be useful for geological mapping. It has been these images which have allowed a team of researchers led by the Planetary Science Institute and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory to embark on an effort to understand Ariel’s likely interior structure and how its dramatic surface features might have been produced.

First, we mapped out the larger structures that we see on the surface, then we used a computer program to model the tidal stresses on the surface, which result from distortion of Ariel from soccer ball-shaped to slight football-shaped and back as it moves closer and farther from Uranus during its orbit. By combining the model with what we see on the surface, we can make inferences about Ariel’s past eccentricity and how thick the ocean might have been.

– Study co-author Alex Patthoff, Planetary Science Institute

The movement of the moon towards and away from Uranus – its orbital eccentricity –is important, because it represents how much the moon is being affected by different gravitational forces from Uranus and the other four globular moons dancing around the planet. Forces which can causes stresses within the moon which might act as engines for generating the kinds of surface features imaged by Voyager 2.

Overall the team calculate that in the distant past, Ariel’s eccentricity was likely around 0.04. This doesn’t sound much, but it is actually 40 times greater that Ariel’s current eccentricity, suggesting that its orbit around Uranus was once more elliptical than we see today, but over the aeons it has gradually moved toward becoming more circular.

However, and more particularly, an eccentricity of 0.04 is actually four times greater than that of Jupiter’s Europa – a moon in an almost constant state of flux thanks to the gravitational influences of Jupiter and the other Galilean moons that it may well have a deep subsurface liquid ocean kept warm by geothermal venting powered by similar gravitational forces that may have been / are affecting Ariel.

Thus, if Ariel conforms to the Europan model, the team suggest that it could potentially harbour a liquid or semi-liquid water ocean, and that at one time, during the period of greatest orbital stresses, this ocean could have been entirely liquid in nature and some 170 kilometres deep. Such an ocean, the modelling revealed, would be fully capable of helping to produce surface features on Ariel of the same nature as those seen by Voyager 2, thanks to the internal stresses and movement of such a volume of water.

This same team carried out a similar study of tiny (just 470 km in diameter) Miranda. It also has curious surface features, a density suggesting it likely has an icy interior and a position where it is subject to contrasting gravitational forces courtesy of Uranus and the other moons. Applying their modelling to the available images data of Miranda also taken by Voyager 2, the team concluded there is a strong potential that at some point in the past, it may have had a subsurface liquid water ocean, although this may have long since become partially or fully frozen.

Whether or not either of these tiny moon does have any remaining subsurface liquid water, or whether their interiors have long since frozen, is obviously unknown. The team also admit that their work is entirely based on data gathered by Voyager 2 on the southern hemispheres of Miranda and Ariel; the nature of their northern hemispheres being entirely unknown. As such, a future study on both northern hemispheres might reveal factors and features that could dramatically change our understanding of both moons and their possible formation, and thus change the findings in both studies.

But for the meantime, two more potentially subsurface hycean moons in the solar system can be added to the list of such bodies.