I’ve written about the issues of space debris on numerous occasions in these pages (for example, see: Space Sunday: debris and the Kessler syndrome; more Artemis or Space Sunday: Debris, Artemis delays, SpaceX Plans). Most of these pieces have highlighted the growing crowded nature of space immediately beyond our planet’s main atmosphere, the increasing risk of vehicle-to-vehicle collisions and the potential for a Kessler syndrome event.

However, there is another aspect of the increasing frequency of space launches and the number of satellites and debris re-entering the atmosphere: pollution and an increase in global warming. This is something I covered in brief back in October 2024, and it is becoming a matter of growing concern.

Currently, there are 14,300 active satellites orbiting Earth (January 2026), compared to just 871 20 years ago. Some 64.3% of these satellites belong to one company: SpaceX, in the form of Starlink satellites. Launches of these commenced in 2019, with each satellite intended to operate between 5 and 7 years. However, because of their relative cheapness, combined with advances in technology and the need for greater capabilities means than since August 2025, SpaceX has been “divesting” itself of initial generations of their Starlink satellites within their anticipated lifespan at a rate to match the continued use of newer satellites, freeing up orbital “slots” for the newer satellites.

As a result, SpaceX is now responsible for over 40% of satellite re-entries into the atmosphere, equating to a net of over half a tonne of pollutants – notably much of it aluminium oxide and carbonates – being dumped into the upper atmosphere a day, all of which contributes to the greenhouse effect within the upper atmosphere.

These particulates drift down into the stratosphere where monitoring is showing they are having some disturbing interactions with everything from the ozone layer through to weather patterns.

We’re really changing the composition of the stratosphere into a state that we’ve never seen before, much of it negative. We really don’t understand many of the impacts that can result from this. The rush to space risks disrupting the global climate system and further depleting the ozone layer, which shields all living things from DNA-destroying ultraviolet radiation.

– John Dykema, applied physicist at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard

In a degree of fairness to SpaceX – who will continue to dominate the issue of re-entry pollutants if their request to deploy a further 15,000 Starlink units is approved – they are not the only contributor. One Web, Amazon, Blue Origin and China via their Qianfan constellation, all stand to add to the problem – if on something of a smaller scale (Amazon and Blue Origin, for example, only plan to operate a total of 8,400 satellites, total). Further, NASA itself is a contributor: the solid rocket boosters used by the space shuttle and now the Space Launch System have been and are major depositors of aluminium and aluminium oxides in the upper atmosphere.

Nor does it end there. The vehicles used to launch these satellites are a contributing factor, whether semi-reusable or expendable. They add exhaust gases – often heavy in carbonates – into the atmosphere, as well as continuing to the dispersion of pollutants in the upper reaches of the atmosphere as upper stages re-enter and burn up.

Carbonates and things like aluminium oxides are of particular concern because of their known impact on both greenhouse gas trapping and in the destruction of the ozone layer. A further factor here is that research suggests that interactions between aluminium oxide and solar radiation in the upper atmosphere can result in the production of chlorine in a highly reactive form, potentially further increasing ozone loss in the atmosphere.

We’re not only putting thermal energy into the Earth’s climate system, but we’re putting it in new places. We don’t really understand the implications of changing stratospheric circulation. It could cause storm tracks to move. Maybe it could shift climate zones, or possibly be a new source of droughts and floods. Chlorine is one of the key actors in the ozone hole. If you add a new surface that converts existing chlorine into reactive and free radical forms, that will also promote ozone loss. Not yet enough to create a new ozone hole, but it can slow the recovery that began after the 1987 Montreal Protocol phased out chlorofluorocarbons.

– John Dykema, applied physicist at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard

There is something of a complex balance in all of this. We need the capabilities an orbital infrastructure can provide – communications, monitoring, Earth and weather observation, etc., – but we also need to be aware of the potential for debilitating the natural protections we need from our atmosphere together with the potential for pollutants to further accelerate human-driven climate change beyond the ability of the planet to correct.

This is further complicated by the inevitable friction between commercial / corporate need – and much of modern space development is squarely in the corporate domain, where income and revenue are the dominant forces – and governmental oversight / policy making and enforcement. As such, how and when policy makers might act is also subject to some complexity, although many in the scientific community are becoming increasingly of the opinion that action is required sooner rather than later, and preferably on a united front.

Changes to stratospheric circulation may ultimately prove more consequential than the additional ozone loss, because the outcomes are so uncertain and potentially far-reaching. For the moment, many questions are not really amenable to straightforward, linear analysis. The ozone loss is significant, and we’re putting so much stuff up there that it could grow in ways that are not proportional to what has thus far been seen. The question is whether policymakers will act on those concerns before the invisible wake of our spacefaring ambitions becomes impossible to ignore.

– John Dykema, applied physicist at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard

Brief Updates

Artemis 2 Launch targets February 8th As Earliest Opportunity

NASA has announced a new earliest launch target date for Artemis 2: Sunday, February 8th, 2026, some two days later than the initial earliest launch date target.

The decision to push the target date back was taken after the planned wet dress rehearsal (WDR) for the launch – which sees all aspects of a vehicle launch tested right up to the point of engine ignition – was postponed due to extremely cold weather moving in over the Kennedy Space Centre which could have impacted accurate data gathering on the 49-hour test, which had been slated to commence on January 29th, 2026.

The WDR was instead reset for the period of February 1st through 3rd, 2026, with the countdown clock to the start of testing resuming at 01:13 UTC on February 1st. It will run through to the opening of a simulated launch window for 02:00 UTC on February 2nd. This latter part of the test will see the propellant loading system – which exhibited issues during preparations for the 2022 Artemis 1 launch – put through its paces to confirm it is ready for an actual launch.

As a thorough testing of all ground and vehicle systems, and a full rehearsal for all teams involved in a launch, the WDR is the last major step in clearing the SLS and Artemis 2 for it mission around the Moon. It will officially terminate as the simulated launch window opens, some 10 seconds before engine ignition – but data gathering will continue through until February 3rd as the rocket is de-tanked of propellants and made safe. Then will come a data analysis and test review.

The actual crew of Artemis 2 are not participating in the test, but will be observing / monitoring elements of the WDR as it progresses. NASA has a livestream of the pad as the WDR progresses, and a separate stream will be opened during the propellant loading phases of the test.

The push back to February 8th, means that NASA effectively has a 3-day opportunity through until February 11th (inclusive) in which to launch the mission before the current window closes. After that, the mission will have to wait for the March launch window to open.

NASA / SpaceX Crew 12 Looks to February 11th Launch

As NASA primarily focuses on Artemis 2, a second crewed launch is being lined up on the taxiway (so to speak) ready to follow the SLS into space – or possibly launch ahead of it.

NASA and SpaceX have confirmed they are looking at February 11th, 2026 as a potential launch date for the Crew 12 mission to the International Space Station (ISS). The mission will lift-off from Kennedy Space Centre’s launch Complex 39A (LC-39A), just a few kilometres away from the SLS at LC-39B, carrying NASA astronauts Jessica Meir and Jack Hathaway, together with ESA astronaut Sophie Adenot, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev aboard the SpaceX Crew Dragon Freedom.

Officially classified as NASA Crew Expedition 74/75, the four will bring the ISS back up to it nominal crew numbers following the medical evacuation which saw the Crew 11 astronauts make an early return to Earth, as I’ve covered in recent Space Sunday articles.

The preparations for Crew 12’s launch means that in the coming days there will be two rockets on the pads at Kennedy’s Launch Complex 39, each proceeding along its own route to launch. As to which goes first, this depends primarily on how the Artemis 2 / SLS launch preparations go. If it leaves the pad between February 8th and February 10th as planned, then there is nothing hindering Crew 12 lifting-off atop their Falcon 9 booster. However, any push-back to February 11th would likely see Crew 12 delayed until February 12th at the earliest. Conversely, if Artemis 2 is delayed until the March launch opportunity, this immediately clears the way for Crew 12 to proceed towards a February 11th lift-off, with both February 12th and 13th also available.

Habitability of Europa Takes Another Blow

In my previous Space Sunday article, I covered recent studies relating to the potential for Jupiter’s icy moon Europa to harbour life (see: Space Sunday: examining Europa and “The Eye of Sauron”). The studies in question were mixed: one contending that conditions on Europa might lean towards life being present within its deep water ocean, the other being more sceptical about the sea floor conditions required to support life (e.g. the presence of hydrothermal vents).

Now a further study has been published, and it also suggests the chances of life existing in Europa’s ocean are at best thin.

One of the core issues with Europa has been knowing just how thick its ice shell actually is. Some have suggested it could be as little as 2 kilometres thick, whilst others have stated it could be as deep as 30km.

Understanding the thickness of the moon’s ice crust is crucial, as it helps define whether or not processes seen to be at work on the Moon are sufficient enough to have an impact on what might be happening within any liquid water oceans under the ice.

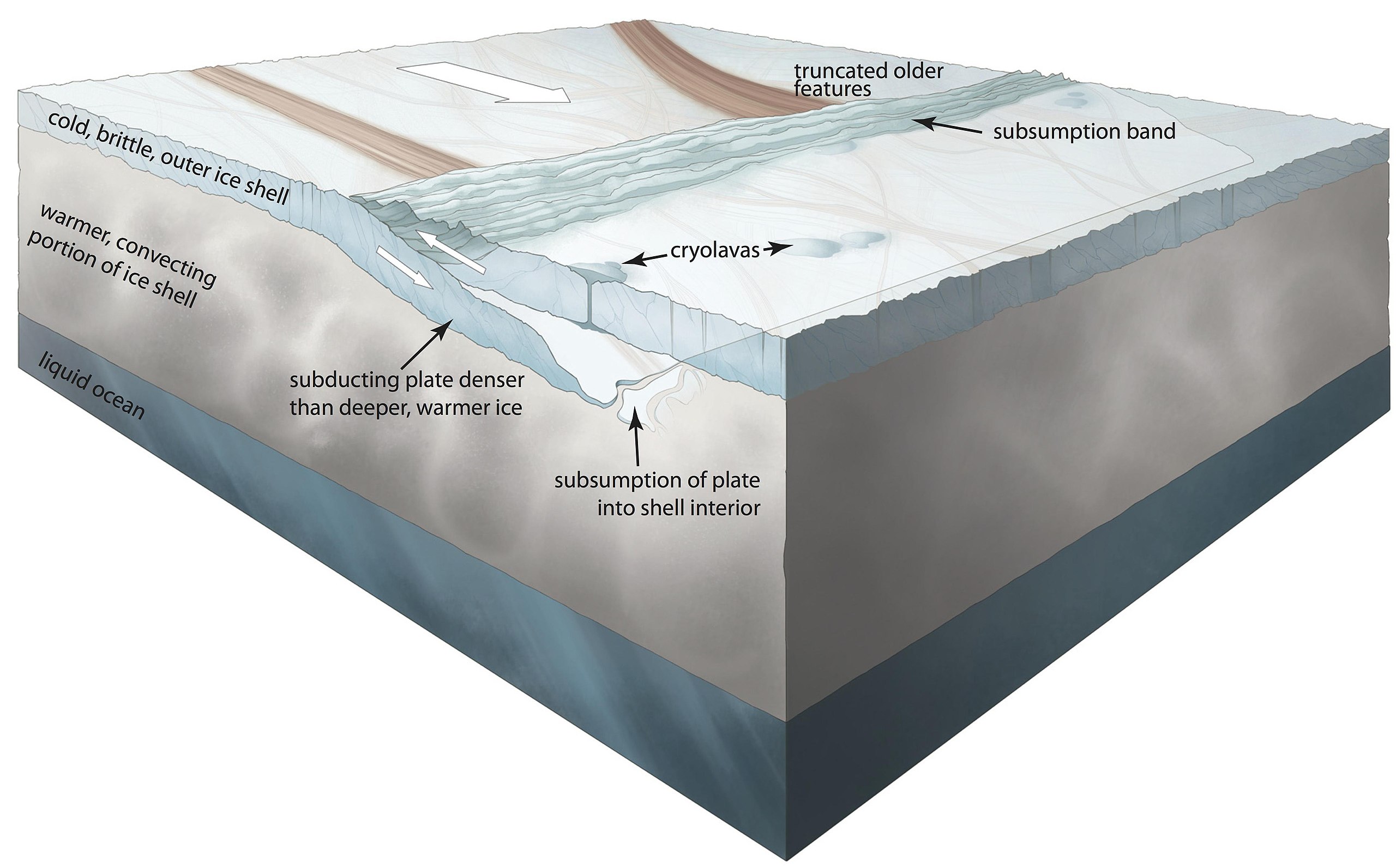

If the ice crust is thin – say a handful of kilometres or less – then activities like subduction within the ice sheets have a good chance of carrying minerals and nutrients created by the interaction between brines in Europa’s surface ice down into the ocean below, where they might help support life processes. similarly, transport mechanisms within the ice could carry oxygen generated as a result of surface interactions down through the ice and into the waters below. If the ice is too thick, then there is a good chance such processes grind to a halt long before they break through the ice crust into the waters below, thus starving them of nutrients, chemicals and gases.

An analysis of data gathered by NASA’s Juno mission as it loops its way around Jupiter and making periodic fly-bys of Europa now suggests that the primary ice crust of Europa is potentially some 28-29 kilometres thick. That’s not good news for the moon’s potential habitability because, as noted it would severely hamper any movement of minerals and nutrients down through the moon’s ice and into the waters below. However, the researchers do note that this doesn’t mean such elements could not reach the waters below, but rather they would take a lot longer to do so, but rather their ability to support any life processes within Europa’s waters would be greatly diminished.

An unknown complication here is he state of the ice towards the bottom of the crust. Is it solid all the way through, or does it become more slush-like as it nears the water boundary layer, warmed by the heat of Europa’s mantle as it radiates outward through the ocean? If it is more slush-like, even if only for around 5 kilometres, this might aid transport mechanisms carrying nutrients, minerals, chemicals and oxygen down into the ocean. Conversely, if the ice is solid and there is a further 3-5 km thick layer of icy slush forming the boundary between it and liquid water, then it will act as a further impediment to these transport mechanisms being able to transfer material to the liquid water ocean.

As a result of this study, and the two noted in my previous Space Sunday article, eyes are now definitely turning towards NASA’s Europa Clipper, due to arrive in orbit around Jupiter in 2030, and ESA’s Juice mission, due to arrive in 2031, in the hope that they will be able to provide more detailed answers to conditions on and under Europa’s ice.