Thursday, November 13th, 2025 witnessed the second launch of New Glenn, the heavy lift launch vehicle from Blue Origin, marking the system as 2 for 2 in terms of successful launches, with this one having the added bonus of achieving an at-sea recovery for the rocket’s first stage, in the process demonstrating some of New Glenn’s unique capabilities.

In all, the mission had four goals:

- Launch NASA’s much-delayed ESCAPADE (ESCApe and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers) mission on its seemingly indirect (but with good reason) way to Mars.

- Carry out a demonstration test of a new commercial communications system developed by private company Viasat.

- Act as a Second National Security Space Launch demonstration, clearing New Glenn to fly military payloads to orbit.

- Successfully recover the first stage of the rocket – which is designed to be re-used over 25 flights – with an at-sea landing aboard a self-propelled ocean-going landing platform.

Of these four goals, the recovery of the first stage booster was regarded more of an added bonus, were it to occur, rather than an overall criteria of mission success. This was reflected in the name given to that first stage: Never Tell Me the Odds (which sci-fi fans may recognise as a quote from the Star Wars franchise – bonus points if you can name the film, scene and speaker! 😀 ).

The first attempt to launch the rocket – officially designated GS1-SN002 with informal reference of NG-2 – was actually made on Sunday, November 9th, 2025. However, this was scrubbed shortly before launch due to poor weather along the planned ascent path for the vehicle. A second attempt was to have been made on November 12th, but this was called off at NASA’s request because – and slightly ironically, given the aim of the ESCAPADE mission – space weather (a recent solar outburst) posing a potential risk to the electronics on the two ESCAPADE satellites during what would have been their critical power-up period had the launch gone ahead.

Thus, lift-off finally occurred at 20:45 UTC on November 13th, with the 98-metre tall rocket rising into a clear sky from Launch Complex 36 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida in what was to be a flawless flight throughout. As with New Glenn’s maiden flight, the vehicle appeared to rise somewhat ponderously into the sky, particularly when compared to the likes of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy.

The reason for this is simple: New Glenn is a very big vehicle, closer in size to NASA’s Saturn V than Falcon 9, and carrying over double the propellant load of the latter. So, whilst they are individually far more powerful than Falcon 9’s nine Merlin engines, the seven BE-4 engines powering New Glenn off the pad have a lot more inertia to overcome, hence the “slow” rise. Falcon Heavy, meanwhile has the advantage in that while it can carry a heavier payload (with a caveat I’ll come back to), it also has an additional 18 Merlin engines to get it going.

- At 3 minutes 9 seconds after launch, having powered the rocket to an altitude of 77 kilometres, the first stage motors shut down and a few second later the upper stage separated, pushed clear of the first stage by a series of spring-loaded rods, allowing it to ignite its two BE-3U motors without damaging the first stage.

- Immediately following this, two significant steps in the flight occurred completely autonomously.

- In the first, the flight control systems on the rocket’s upper stage recognised that the first part of the vehicles ascent had been optimised for first stage recovery, rather than achieving orbit. They therefore commanded a “pitch up” manoeuvre, significantly increasing the upper stage’s angle of ascent, allowing it to reach its intended initial orbit.

- In the second, the first stage used its reaction control systems (RCS) to enter a “coast” phase, essentially a controlled free-fall back towards Earth, re-orienting itself ready to perform a propulsive breaking manoeuvre.

- After 50 seconds of continued ascent following separation, the upper stage of the rocket successfully jettisoned its payload fairings, exposing the two small ESCAPADE satellites, to space.

- Dropping in free-fall for some four minutes, the rocket’s first stage re-lit three of its BE-4 motors at an altitude of around 66 km, slowing its re-entry into the denser atmosphere.

- Following the re-entry burn, the motors shut down and the stage used the aerodynamic “strafes” close to its engine exhausts together with the upper guidance fins, to take over “flying” itself down towards the waiting landing vessel.

- At 8 minutes 33 seconds after launch, the three centre Be-4 motors re-lit again at an altitude of just under 2 km, slowing the stage and bringing it to an upright position in preparation for landing.

It was at this point that New Glenn demonstrated the first of its unique characteristics: it brought itself to a near-hover abeam of the landing vessel prior to deploying its six landing legs. It then gently crabbed sideways until it was over the landing ship before gently lowering itself to a perfect touch-down right in the middle of the landing ring painted on the deck.

Immediately on touch-down, special pyrotechnic “disks” under the booster’s landing legs fired, effectively welding the stage to the deck of the ship to eliminate any risk of the booster toppling over during the return to port.

Called “energetic welding”, this capability has been developed by Blue Origin specifically for New Glenn landings at sea, but is seen as having potential uses elsewhere when “instant bonding” of this kind is required. Once the booster has been returned to port, the bonding disks can be separated from both ship and booster with no damage to the latter and a minor need to replace some of the deck plating on the former.

New Glenn’s ability to hover is also worth addressing. Some have claimed that this capability detracts from New Glenn as a launch vehicle as it reduces the amount of payload it might otherwise lift to orbit. Such claims are misplaced: not only is the amount of propellant used during a hover quite minimal overall, it clearly allows New Glenn to make much more of a controlled landing than can be achieved by the likes of SpaceX Falcon 9 stages, thus increasingly the booster’ survivability. Also, as experience is gained with further stage recoveries, there is no reason to suppose the ability to hover / translate / land cannot be further refined to use less propellant than may have been the case here.

And this point brings me back to comparative payload capabilities. It is oft pointed out that whilst big, New Glenn is a “less capable” launch vehicle than SpaceX Falcon Heavy on the grounds the latter is able to lift 63 tonnes to low Earth orbit (LEO) and 27.6 tonne to Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO), compared to New Glenn “only” being able to manage 45 and 13.6 tonnes respectively.

However, these comparisons miss out an important point: Falcon Heavy can only achieve its numbers when used as a fully expendable launch system, whereas New Glenn’s capabilities are based on the first stage always being recovered. If the same criteria is applied to Falcon Heavy and all three core stages are recovered, its capacity to LEO is reduced to 50 tonnes – just 5 more than New Glenn, whilst its ability to launch to the more lucrative (in terms of launch fees) GTO comes down to 8 tonnes; 5.6 tonnes less than New Glenn (if only the outer two boosters on a Falcon Heavy are recovered, then it can lift some 16 tonnes to GTO; 2.4 tonnes more than New Glenn). Given that reusability is supposedly the name of the game for both SpaceX and Blue Origin, the two launch systems are actually very closely matched.

But to return to the NG-2 flight. While the first stage of the rocket made its way down to a successful landing, the upper stage continued to run its two motors for a further ten minutes before they shut down as the vehicle approached the western coast of the African continent. Still gaining altitude and approaching initial orbital velocity, the upper stage of the rocket “coasted” for 12 minutes as it passed over Africa before the BE-3U motors ignited once again, and the vehicle swung itself onto a trajectory for the Sun-Earth lagrange L2 position, the two ESCAPADE satellites separating from it some 33 minutes after launch.

ESCAPADE: the Long Way to Mars

That New Glenn launched the ESCAPADE mission to the Sun-Earth L2 position rather than on its way to Mars has also been a source for some confusion in various circles. In particular, a common question has been why, if New Glenn is so powerful, could it not lob what is a comparatively small payload – the two ESCAPADE satellites having a combined mass of just over one tonne – directly to Mars.

The answer to this is relatively simple – because that’s what NASA wanted. However, it is also a little more nuanced when explaining why this was the case.

Interplanetary mission are generally limited in terms of when they can be optimally launched in order to be at their most efficient in terms of required propellant mass and capability. In the case of missions to Mars, for example, the most efficient launch opportunities for missions occur once every 24-26 months. However, waiting for such launch windows to roll around might not always be for the best; there are times when it might be preferable to launch a mission head of its best transfer time and simply “park” it somewhere to wait until the time is right to send it on its way.

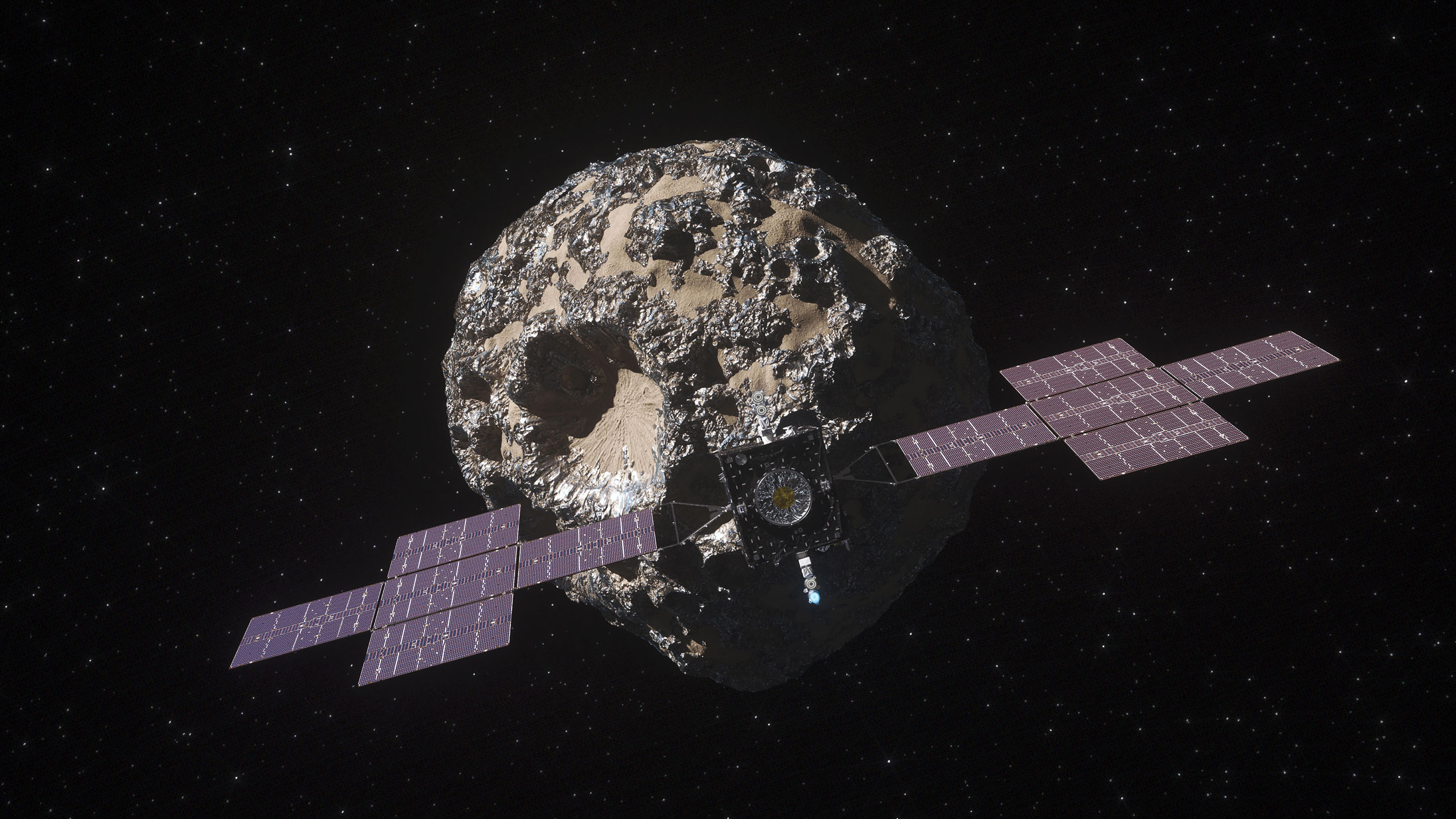

During its development, ESCAPADE – as a low-cost mission intended to be developed and flown for less than US $55 million – had originally been intended to piggyback a ride to Mars aboard NASA’s much bigger Psyche mission. This mission would be heading to asteroid 16 Psyche, but in order to reach that destination, it would have to perform a fly-by gravity assist around Mars. Thus, it became the ideal vehicle on which ESCAPADE could hitch a ride, separating from the Psyche spacecraft as the latter approached Mars in May 2026.

However, Psyche’s launch was pushed back several times, such that by the time it eventually launched in October 2023, the additional delta-vee it required in order to still make its required fly-by of Mars was so great, there was no way the two ESCAPADE satellites could carry enough propellants to slow themselves into orbit around Mars after Psyche dropped them off. Thus, the mission was removed Psyche’s launch manifest.

Instead, NASA sought an alternative means to get the mission to Mars, eventually tapping Blue Origin, who said they could launch ESCAPADE on the maiden flight of their New Glenn vehicle at a cost of US $20 million to NASA, and do so during the 2024 Mars launch window opportunity.

Unfortunately, that maiden flight of New Glenn was in turn pushed back outside of the Mars 2024 launch window (eventually taking place in January 2025), leaving it unable to both launch ESCAPADE towards Mars and achieve its other mission objective of remaining in a medium-Earth orbit to demonstrate a prototype Blue Ring orbital vehicle. And so NASA opted to remove ESCAPADE from that launch and instead opt to test out the theory of using parking orbits for interplanetary missions, rather than leaving them on the ground where they might eventually face cancellation – as was the case with Janus, another mission which was originally to have flown with the Psyche mission, but was also pulled from that launch due to its repeated delays.

Using ESCAPADE to test the theory of parking orbits also made sense because of the mission’s function: studying the Martian magnetosphere and its interaction with the Solar wind. Whilst the Sun-Earth L2 position doesn’t have a magnetosphere, it is subject to the influence of the solar wind. Given just how valuable a piece of space real estate its is proving to be with several mission operating in orbits around it, understanding more about the role the solar wind and plasma plays in the overall stability of the region makes a lot of sense – and ESCAPADE’s science capabilities mean its two satellites can carry out this work whilst they loiter there through 2026.

Currently, both satellites are performing well, having unfolded their solar arrays and charged themselves up. As noted, they will make a fly-by of Earth in late 2026 to slingshot themselves on to Mars, which they will reach in 2027. On their arrival, they will initially share a highly elliptical orbit varying between 8,400 km and 170 km above the surface of the planet, operating in tandem for six months. After this, they will manoeuvre into different orbits with different periods and extremes, allowing them to both operate independently to one another in their observations and to also carry out comparative studies of the same regions of the Martian magnetosphere from different points in space.

What’s Next for New Glenn?

As of the time of writing, Never Tell Me the Odds remains at sea aboard the landing platform vessel Jacklyn. Following its successful landing, the booster went through an extensive “safing” procedure managed by an automated vehicle, during which propellants and hazardous gasses were removed, and its systems purged with inert helium. Assuming it is in a condition allowing it to be refurbished and reused as planned following its return to dry land, the stage will most likely re-fly in early 2026 as part of an even more ambitious mission.

GS1-SN002-2, provisionally aiming for a January 2026 launch, is intended to fly the Blue Moon Pathfinder mission to the Moon, where it will attempt a soft landing as part of a demonstration of capabilities required for NASA’s Project Artemis. Blue Moon is the name given to Blue Origin’s family of in-development lunar landing craft, with Blue Moon Mark 1 being a cargo vehicle capable of remote operations and delivering around 3 tonnes of materiel to the surface of the Moon per flight, and Blue Moon Mark 2 being a larger crewed vehicle capable of delivering up to 4 people at a time to the Moon for extended periods.

Both of these craft use common elements: avionics, propulsion systems (the BE-7 cryogenic engine), navigation and precision landing systems, data and communications systems, etc. Blue Moon Pathfinder is intended to demonstrate all of these systems and capabilities, landing the vehicle on the Moon within 100 metres of a designated landing point. If successful on all counts, GS1-SN002-2 will not only demonstrate / confirm the reusability of the New Glenn first stage, it will provide a very clear and practical demonstration of Blue Origin’s emerging lunar mission capabilities, something which may well justify claims that the company is somewhat ahead of SpaceX in having a lunar landing capability that could meet the 2027/28 launch time frame for Artemis 3, the first crewed mission of the programme intended to land on the Moon.