In my previous piece on the NASA upcoming budget, as being put forward by the US 47th executive administration, I focused on how the proposal could impact NASA’s science capabilities. At the time, the entire budget request had yet to be published, and my article was based on what had been made public by way of passback documents circulating in Washington DC.

At that time, it was anticipated that the White House would push for around a 20% cut in NASA’s annual budget, the majority of which would target NASA’s Earth and Space Science operations. However, on Friday, May 2nd, 2025, the “skinny” version of the White House budget request was published, revealing that the administration is seeking an overall 24.8% cut in NASA’s spending compared to the agency’s existing budget. If enacted, it will be the biggest single-year cut in NASA’s entire history. And whilst around two-thirds of the proposed cuts do land squarely on NASA space / Earth science and legacy programmes, they do touch the agency’s human spaceflight ambitions as well.

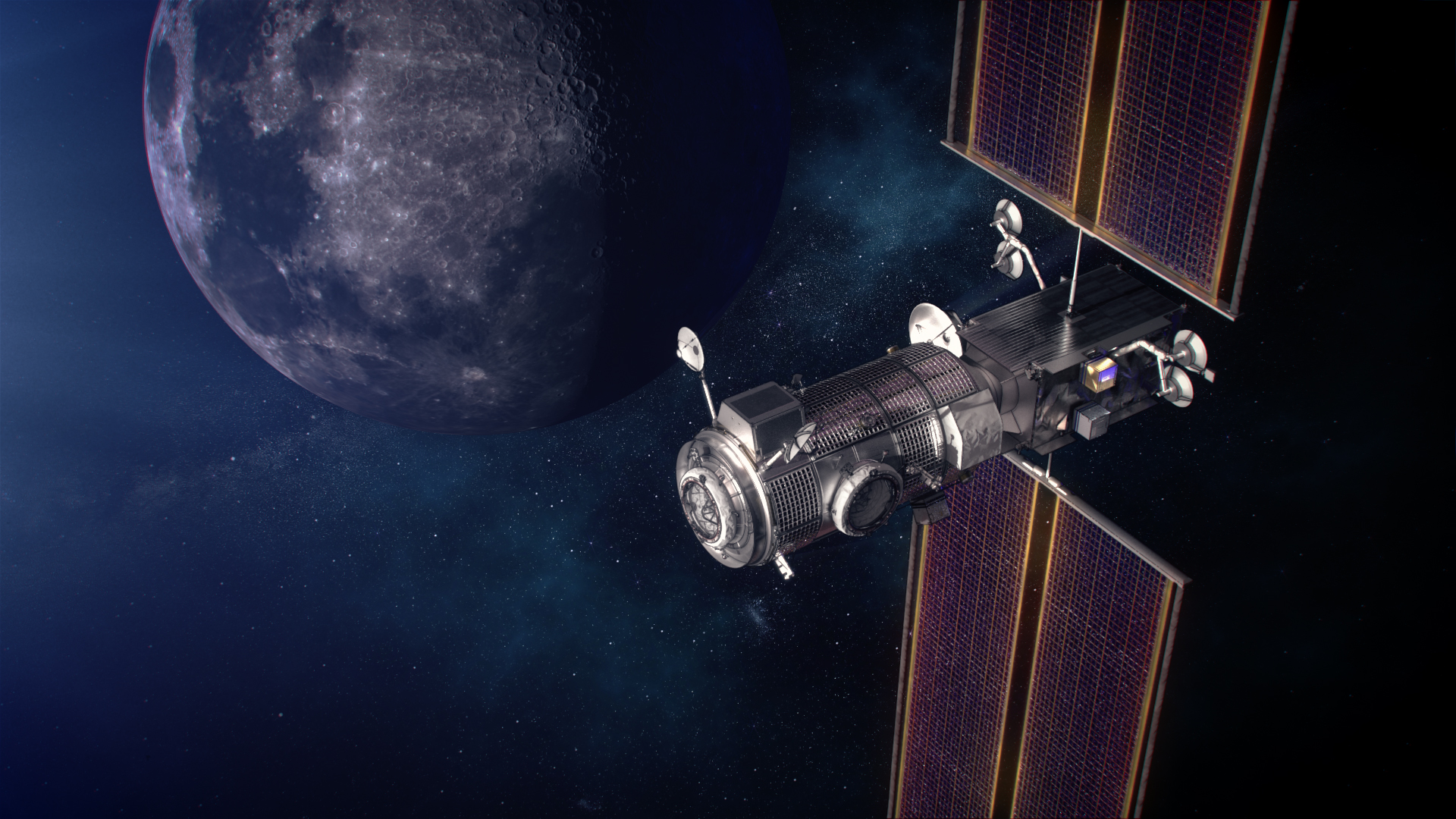

First and foremost, the request calls for the immediate cancellation of the Lunar Gateway station (aka “Gateway”). This actually makes sense, simply because since its inception, Gateway has itself never made sense.

Starting as a series of studies called the Deep Space Gateway (DSG) in the mid-2010s, it became an official NASA project under – ironically – the first Trump Administration, when it became the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway (LOP-G). It was presented at both a means to enable a return to the surface of the Moon and a gateway to the human exploration of the solar system. However, intended to occupy a Polar near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) around the Moon, travelling up to 70,000 km from the lunar surface whilst never coming closer than 3,000 km, it has been more a limitation than an enhancement to lunar operations.

While this orbit would allow for uninterrupted communications between the station and Earth, it also introduced multiple complexities of operation into any return to the Moon. As a result, multiple ancillary reasons for Gateway’s existence were cooked up: Earth sciences, heliophysics, fundamental space biology research, etc., all of which could be achieved more directly and cost-effectively through other means.

Thus, over the last 6 years Gateway has been consistently downsized and de-prioritised, constantly criticised by experts from within and outside NASA, and even seen as something of a complicated boondoggle in terms of design by those actually engaged in its design. Add to this the fact it offers little or nothing to lunar operations that could not be achieved from within a modest lunar orbit (200-300 km). Given all this, cancelling the project – even if it means pissing off international and commercial partners – is a sensible move.

As I noted in a recent Space Sunday report, the arrival of the Trump administration coincided with calls for the outright cancellation of NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) on the ground of outright expense. but as I mentioned in that piece, any such complete cancellation of SLS would have left Artemis high and dry, and ideas of simply launching Orion utilising other launchers were as close to be nonsensical as to make no difference.

In a follow-up piece to that article, I suggested that a preferable approach would be to go ahead with Artemis with SLS until such time as the latter could be replaced. This is more-or-less what the Trump budget proposes, albeit it on a far tighter time frame; looking to “phase out” both SLS and Orion completely following the first lunar landing of the Artemis programme (Artemis 3), in favour of a “commercial” solution.

Given that Artemis 3 is unlikely to fly before around 2028/9 (simply because the SpaceX lunar lander is unlikely to be ready before then), this does present an – albeit tight – window of opportunity; albeit one biased in favour of one commercial operator – SpaceX.

That company’s Crew Dragon vehicle has proven itself a remarkably versatile vehicle, capable of not only ferrying crews to the International Space Station, but also of carrying out space missions of 4-5 days duration in its own right. While its life-support and general facilities would require upgrade, as (likely) would the heat shield (which would have to protect the vehicle when re-entering Earth’s atmosphere at around 40,000 km/h compared to the 28,000 km/h experienced during a return from low-Earth orbit (LEO). But such upgrades are necessarily outside the realm of possibility.

A critical part of these upgrades would lie with the service module (aka “trunk”) supplying power and consumables (e.g. water and air) to Crew Dragon. This would have to be considerable beefier in terms of propellants and consumables it can carry, and also its propulsion. However, this is not something insurmountable. SpaceX has been working on a design for a “Dragon XL”, a large-capacity Cargo Dragon supported by an enhanced “trunk” which would have been used to support operations at Gateway. In theory, there’s a potential for this “trunk” to be enhanced into a suitable service module for Crew Dragon, allowing it to make trips to lunar orbit and back.

This does involve a number of challenges – one of them being how to launch such a combination. Currently, the heaviest payload SpaceX can send to the Moon is between 20-24 tonnes, using the Falcon Heavy (I am intentionally ignoring Starship here, as that is a long way from being anywhere near an operational, human-capable launch system). However, it’s unlikely a combined Crew Dragon + enhanced service module is going to fall within this limit (for example, the Apollo Command and Service modules massed 28.8 tonnes and Orion and its lightweight ESM mass 26.5 tonnes). Falcon Heavy is also not human-rated, so even if it could lob a Crew Dragon / enhanced service module combination to the Moon, it would need to undergo some degree of modification in order to gain a human flight rating, adding further complications.

That said, even this is not a blocker: allowing for the risk of damage to the Crew Dragon’s heat shield, it might be possible to launch a crew to LEO atop a Falcon 9, allowing then to rendezvous and mate with an uprated service module and Falcon upper stage placed in to LEO by a Falcon Heavy. This would eliminate the need to human-rate Falcon Heavy whilst enabling the latter to launch a more capable combination of upper stage (to boost the combined Crew Dragon and service module onwards to the Moon) and service module to await the arrival of the Crew Dragon.

As noted, there are technical caveats involved in this approach. It also requires the provisioning of funding for said vehicle development – something not within the pages of this budget proposal; and it would make NASA exceptionally dependent on SpaceX for the success of Artemis.

Beyond changes NASA’s lunar ambitions, the 2026 budget request is seeking a reduction in International Space Station (ISS) spending of around half a billion dollars a year on 2024 spending, in “preparation” for the station’s 2030 decommissioning. The most immediate impact of the cut will be a reduction in overall ISS crew sizes, together with a reduction in the number of annual resupply missions – something that could impact the likes of Sierra Space with their contract for ISS resupply flights due to commence in 2026. In addition, the budget request seeks to “refocus” (aka “restrict”) research and space science activities in the ISS to those directly related to “efforts critical to the moon and Mars exploration programmes”. However, what this precisely means is not made clear.

Whilst promoting human mission to Mars, the budget proposal offers little if anything concrete, other than the cancellation of the automated Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission, stating the return of any samples can be deferred until such time as humans reach Mars and can collect such samples directly.

In this, MSR is the only science mission named for cancellation in the budget request. Given the manner in which NASA has consistently fumbled around with the mission over that last half-decade, its cancellation doesn’t come as a surprise. The non-mention of other programmes also doesn’t mean the concerns I raised in my previous Space Sunday have gone away; as noted, the budget request confirms the desire to make very deep cuts into NASA’s ability to carry out science and research across all disciplines.

Two additional programmes potentially impacted in this regard are the LandSat Earth imagining programme – which the Trump administration wants to see downscaled, and NASA’s research into what the administration calls “legacy space programmes” – such as their research into nuclear propulsion systems. The latter is again ironic given nuclear systems are potentially the most effective means of propulsion for Mars missions, and the budget request flag-waves the idea of humans to Mars.

As with Trump’s first term in office, the White House is seeking to eliminate all of NASA’s involvement in STEM and education (STEM being disgustingly referenced as being “woke” in the budget request). This includes cancelling the Established Programme to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR). This is again ironic, given that during his initial Senate confirmation hearings, prospective NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman (who is now almost certain to be confirmed, following a 19-9 vote by the Senate Commerce Committee) referred to EPSCoR as an “essential” NASA educational programme because “it helps connect students and researchers from underserved regions and institutions to the opportunities that NASA provides.”

In my last update, I noted that there is a reported desire among some within the Administration to see at least one NASA centre – The Goddard Space Flight Centre – to be closed. While the budget request does not directly earmark any NASA centres for closure, it does call for NASA to “streamline the workforce, IT services, NASA Centre operations, facility maintenance, and construction and environmental compliance activities”. As such, downsizing / closures remains a threat, and Goddard remains the centre with direct responsibility for many aspects of NASA’s science missions.

All of the above said, this is – at this stage at least – only a budget request. It remains to be seen as to how those in both side of Capitol Hill respond, and whether the White House will actually listen if / when objections are raised. Given the attitude of many within (notably, but not exclusively) the Republican Party towards science, climate change, the environment, DEI (which the budget also targets), green initiatives, etc., I have my doubts as to whether strong objections to the cuts to NASA’s science programmes will be raised.

Certainly there has been some push-back from within the bipartisan U.S. Planetary Science Caucus, but thus far the loudest voices of protest have come from outside US government circles, such as the globally-respected American Astronomical society and The Planetary Society – two organisations well-versed in America’s leadership in the fields of space and science – among others.

If enacted, the 56% cut to the National Science Foundation, the 47% cut to NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, and the 14% cut to the Department of Energy’s Office of Science would result in an historic decline of American investment in basic scientific research. These cuts would damage a broad range of research areas that will not be supported by the private sector. The negative consequences would be exacerbated because many research efforts can require years to decades to mature and reach fruition. Without robust and sustained federal funding, the United States will lose at least a generation of talent to other countries that are increasing their investments in facilities and workforce development. This will derail not only cutting-edge scientific advances, but also the training of the nation’s future STEM workforce. These proposed cuts will result in the loss of American leadership in science.

– from a statement issued by the American Astronomical Society, May 2nd, 2025

As it is, NASA is already tightening its belt: on April 29th, 2025, it postponed the release of the Announcement of Opportunity (AO) for the next Small Explorer (SMEX) mission.

Established in 1988 as a continuation of and enhancement to the long-running Explorer Programme, SMEX focuses on well-defined and relatively inexpensive space science missions in the disciplines of astrophysics and space physics which cost less than US $170 million per mission (excluding launch). Currently, the last SMEX mission was selected in 2021, but its launch has been delayed until 2027. As such, the 2025 AO would have earmarked a launch window between 2027 and 2031 for the selected mission. However, given the potential for up to two-thirds of the agency’s astrophysics budget to be cut, NASA has indicated it would not now issue the SMEX AO “until at least 2026”.

It is anticipated that more upcoming requests for science mission proposals will be placed “on hold” whilst this budget request is debated.