When it comes to the Galilean moons of Jupiter, we tend to focus a lot of attention on the icy moon of Europa due to the potential of it being home to a subsurface ocean. However, Europa is not alone in being a fascinating place among these four moons; between it and Jupiter sits Io, the most geologically active place in the solar system – and that’s just one of the facts relating to it.

As the 4th largest Moon in the solar system and the third largest of the Jupiter’s Galilean moons, Io is slightly larger than our own Moon and has more than 400 active volcanoes across its surface. In addition, it has both the highest density and strongest surface gravity of any moon in the solar system. Its extreme volcanism is powered by gravitational flexing, the result of Io constantly being pulled in different directions by the gravities of Jupiter and the other three Galilean moons generating tidal heating deep in Io’s core, the same mechanism which is thought give Europa it’s possibly liquid water ocean. but on a much hotter and more violent scale.

Io’s volcanism is such that the almost constant lava flows mean the moon’s surface is constantly being re-formed outside of its volcanic peaks, whilst the allotropes and compounds of sulphur carried to the surface by both eruptions and lava flows give rise to the moon’s unique colouring. In addition, many of the volcanoes pump material high enough above Io to form a strange, tenuous atmosphere, noticeably more dense around such eruptions than elsewhere. This ejecta also gives rise to a large plasma torus around Jupiter.

The Jovian system has been the subject of extensive study by NASA’s Juno mission since it originally arrived in its extended orbit around the planet in July 2016. Since then, the vehicle had made more than 50 complete passes around the planet in a roughly polar orbit, and some of those have periodically allowed the spacecraft to observe the major moons of Jupiter, including Io. Two of the most recent of these flybys – in May and July 2023 – focused on Io, once again revealing the moon is incredible detail.

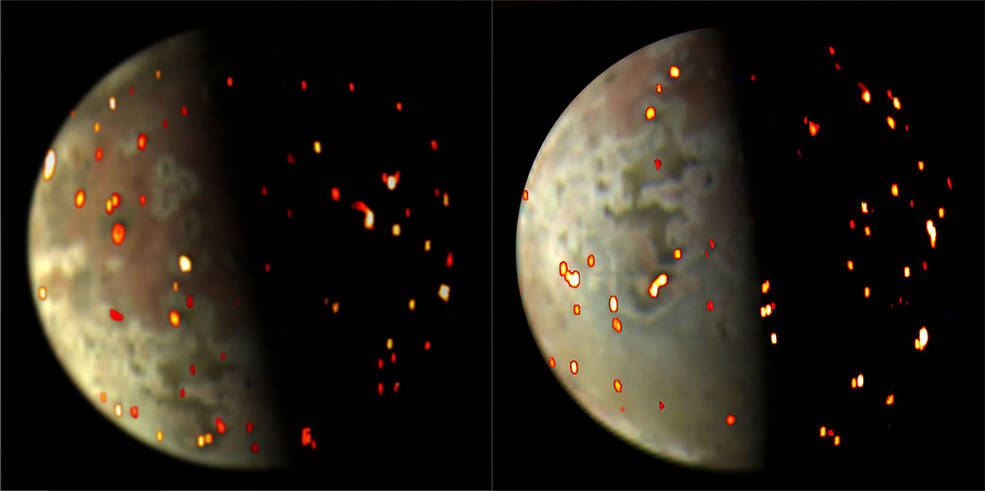

The May 16th, 2023 flyby brought the Juno spacecraft to just 35,500 km of Io, allowing the imagers on the spacecraft to capture the moon simultaneously in both visible light wavelength and in the infrared, revealing a stunning amount of details on the moon’s volcanism.

In July, Juno passed even closer, at just 22,000 km from the moon’s surface. This allowed an actual eruption to be imaged by the spacecraft – not the first time this has happened, but one which captured Io’s “old faithful” once again in action.

“Old faithful” is the name given to the Prometheus Patera, a volcanic pit on the side of the moon facing away from Jupiter (Io is tidally locked to Jupiter), an area given to near-continuous eruptions which have been observed by both of the Voyager spacecraft, together with Galileo, and New Horizons, as well as Juno. Outflow from the eruptions in the pit covers an area of almost 7,000 square km, and it causes an observable plume of material rising up to 100 km above the moon’s surface.

What is particularly remarkable about Juno’s images of Io and the other Galilean moons is not only the amount of information they are providing, but the fact the spacecraft wasn’t ever designed to study them; its instruments were specifically designed to uncover secrets of Jupiter’s atmosphere and interior. But as remarkable as these images are, they are just a foretaste of what is to come.

Three more even closer flybys of Io will come in October and December before the spacecraft makes its closest approach of the mission to date, passing just 1,500 km above the Moon’s surface. Meanwhile, to mark Juno’s May and July 2023 flybys, NASA released a video offering a “starship captain’s” view of Io as the spacecraft passed around Jupiter’s limb. The music featured in the video is from Juno to Jupiter, by Vangelis. This was the Greek composer’s last studio album prior to his passing in May 2022, and the last of a series of albums and shorter pieces he wrote for both NASA and ESA between 2001 and 2021 and born of his almost life-long passion for science and space exploration.

Russia Heads Back to the Moon

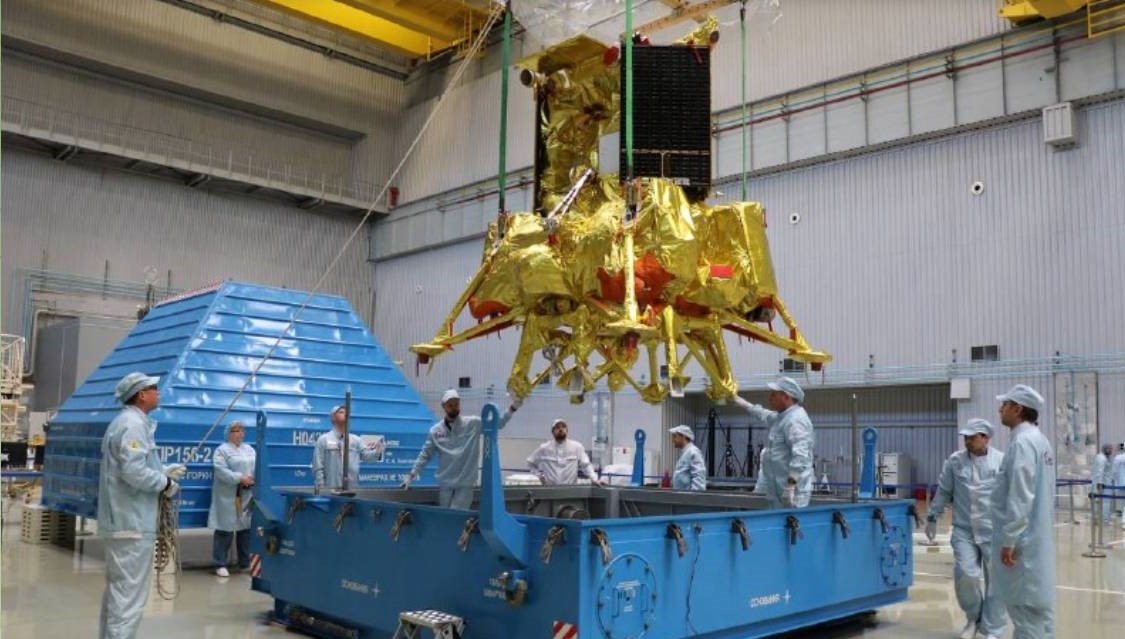

At 23:10 UTC on August 10th, 2023 (09:10, August 11th, local time) a Soyuz 2.1b/Fregat booster lifted-off from Russia’s far eastern Vostochny Cosmodrome to mark the first lunar mission Russia has undertaken in 47 years. Originally called Luna-Glob, the mission is designed to place a robust lander within the crater Boguslawsky in the lunar South Polar Region.

Initial concepts for the mission started in 1998, and Russia had planned to garner international involvement, looking to partner with (at various times) the likes of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the European Space Agency and the Swedish National Space Agency (SNSA) and the project gradually matured. However, given the 20+ year gestation for the mission, ISRO and JAXA switched to their own lunar-focused programmes whilst SNSA eventually partnered with China, flying their LINA-XSAN instrument aboard Chang’e 4 in 2019. ESA also withdrew from cooperation with Russia as a result of the invasion of Ukraine.

As a national mission, the project and its lander were renamed Luna 25, intended to suggest a direct lineage back to 1976’s Luna 24 sample return mission. It was launched very much in the public eye: Russia Television broadcast and streamed the event live in a 90-minute programme which featured the launch itself, coupled with a strange mix of a choir of young children singing under a huge photograph of Yuri Gagarin, a candlelit display.

Filmed at the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, Moscow, this portion of the programme also featured interviews with cosmonauts Oleg Artemyev and Oleg Blinov and more music, this time from Russian rock/pop group UMA2RMAN.

The mission is seen as the starting point for Russia’s own renewed lunar aspirations. A prime aim of the spacecraft is to test new landing technologies and systems which could be used in future missions to the Moon, including those by crews – in this respect, Artemyev and Blinov discussed the development of lunar habitats from a small-scale outpost (with artwork supplied by Roscosmos) through to a large-scale base (with a rendering by Russia Television, rather than anything official).

As well as lander research, the 1.7-tonne lander will conduct studies of the upper layer of the lunar regolith, appraise the ultra-thin lunar atmosphere and search for signs of water ice in the south pole region. To achieve this, the upper platform of the lander contains 30 kg of science payload. The landing itself is scheduled for August 21st, 2023, after a spiral cruise out to the Moon, and which means that Luna 25 should touch down some two days ahead of India’s Chanrayaan-3 lander launched in July and which achieved its initial orbit around the Moon on August 6th.

In Brief

The Downs and Ups of Ingenuity’s 53rd and 54th Flights

In my last Space Sunday article, I noted that NASA’s Mars helicopter drone Ingenuity had completed its 53rd flight on July 22nd, with all the details of the flight only being confirmed in August – which was a little slow compared to past flights.

It has since been confirmed that the 75-second flight was actually cut short as a result of a “LAND_NOW” command sequence being triggered just 25 second or so into Ingenuity’s horizontal flight, causing it to do exactly that – land. The full duration of the flight should have been some 136 seconds, with around 80-90 seconds in horizontal flight.

The event which triggered the command is still under investigation, but it is believed a glitch in the real-time scanning pipeline of images from the drone’s navigation camera meant that terrain being seen did not match data from its inertial measurement unit (IMU), leading the flight software to believe the craft was veering off-course, triggering the landing.

Software updates were sent to the craft to further correct the issue, and a test flight was made on August 3rd under the watchful eye of the Perseverance rover to give a further data point if any anomalies occurred. This flight – number 54 for Ingenuity – was little more than a straight up-and-down, but it was enough to test the syncing of images from the nav camera with data from the IMU.

“LAND_NOW” was a software update initially delivered to Ingenuity after a similar timing glitch caused the drone to enter into a series of unexpected pitches and rolls whilst hovering on its 6th flight in May 2021. It is intended to handle such timing errors and around half-a-dozen other issues which may affect Ingenuity’s flight, but flight 53 marked the first time it has actually been triggered.

SpaceX to Trigger Artemis 3 Mission Change?

Plans for NASA’s Artemis 2 November 2024 crewed flight around the Moon continue on schedule. The four-person crew are engaged in mission training, and all the critical hardware elements – the Space Launch System core rocket, its boosters, the Orion MPCV capsule and its European-built Service Module and upgrades to the mobile launch platform and service tower (both of which suffered damage during the launch of Artemis 1 on December 11th, 2022) – are on track.

However, the same cannot be said for Artemis 3, the planned mission to land a crew of two on the surface on the Moon in either December 2025 or in early 2026. Speaking on August 8th, 2023, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Exploration Systems Development (i.e. the individual in charge of NASA’s entire Moon-Mars mission architecture), James Free, admitted the agency was investigating “alternative” mission options for Artemis 3 to an actual landing.

Whilst not directly pointed to as the reason for NASA re-evaluating Artemis 3’s mission goals, Free’s general comments indicated that NASA remains concerned at SpaceX’s ability to deliver the Human Land System (HLS) vehicle required to shuttle a crew between lunar orbit and the surface of the Moon in a manner which meets the lunar landing schedule.

The SpaceX HLS is intended to be an evolved version of their Starship heavy lift vehicle; however it remains unclear how far the company is in actually developing the vehicle. Further, the SpaceX HLS requires significant supporting infrastructure: not only does it require the Super Heavy booster to launch it, it requires on-orbit refuelling once in Earth orbit (which will require between 4-8 additional Starship launches utilising a yet-to-be-developed tanker version+ the means to actually transfer fuel between the tankers and HLS), as well as the thorough testing of the HLS landing systems.

Free’s concerns were voiced after he and others had attended a day-long meeting with SpaceX engineers which he said offered “tremendous insight” into the Starship / Super Heavy / HLS development path, but which would require time for NASA to “digest” before any further commitment is given to a late 2025 / early 2026 lunar landing attempt or whether Artemis 3 will be repurposed and the landing attempt pushed further back.

Boeing Confirm Starliner Crewed Flight Delayed. Again

Boeing has confirmed the first crewed flight of their CST-100 Starliner capsule intended to carry crews to / from the ISS will now fly “no earlier” than March 2024, this time due to concerns over the vehicle’s parachute system and the use of flammable material within the vehicle’s electrical wiring.

The parachute issue is related to so-called soft links in the parachute system. These connect the parachute canopy rigging with the main harness supporting the vehicle, and have proven weaker than anticipated for crewed flights, prompting a redesign, which in turn has prompted a further test of the parachute system ahead of any flight – and this is unlikely to be much before November 2023.

Boeing is not alone in late-breaking parachute system issues: SpaceX had to completely redesign the parachute canopies used for Crew Dragon which the original failed to meet safety standards for crewed mission. However, of greater embarrassment – for NASA – is the use of a tape called P-213 to insulate much of the vehicle’s electrical wiring. The tape had been selected, as a set of NASA records indicated it as acceptable for use in human-rated vehicles; however, it was then found that another safety standard disbarred the tape from use in crewed vehicles do to the fact it can burn when exposed to heat or flame. As such, all of the tape – used in a large proportion of the vehicle’s wiring – needs to be replaced.

While NASA and Boeing are confident Starliner will be ready to fly it’s long awaited Crewed Flight Test (CFT)to the International Space Station by March 2024, the actual flight itself might not actually come until much later in 2024. This is because the schedule for the ISS in the first half of 2024 is very busy in terms of visiting spacecraft, both crewed and resupply. As such, the CFT might not come until later in 2024. This in turn means Starliners is unlikely to enter operational use until 2025.

always enjoy your Sunday blogs on space… good morning.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good morning, and thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person