When discussing the robotic exploration of Mars, the focus tends to be on the current NASA missions: the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover Curiosity and the Mars 2020 rover Perseverance and its flight-capable companion, Ingenuity. This is because of all the active Mars missions, these are the most visually exciting. But it does mean the other missions still operating around Mars – a total of 8, including China’s Tainwen-1 orbiter and Zhurong rover and UAE’s Hope mission – tend to get overlooked.

One of those that tends to get overlooked is actually the second longest running of the current batch, the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, the orbital component of a 2-part mission using the same name. This recently celebrated the 20th anniversary of its launch (June 2nd, 2003) and will reach the 20th anniversary of its arrival in its operational orbit around Mars on December 25th, 2023.

The mission’s title – “Mars Express” – was selected for a two-fold reason. The first was the sheer speed with which the mission was designed and brought together as a successor to the orbital component of the failed Russian Mars 96 mission, for which a number of European Space Agency member nations had supplied science instruments, using an ESA-designed satellite unit (based on the Rosetta mission vehicle).

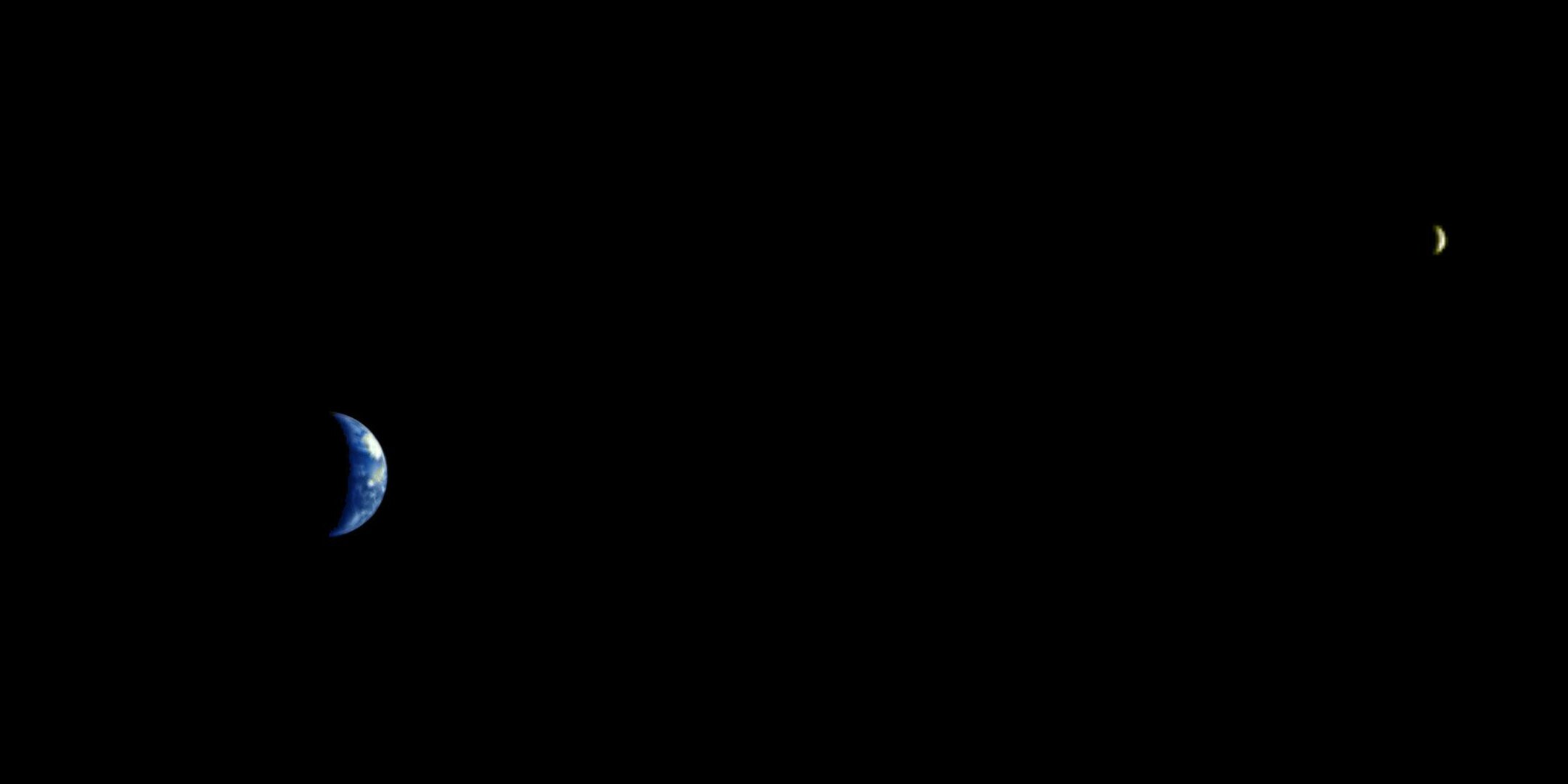

The second was the fact that 2003 marked a particularly “close” approach of Earth and Mars in their respective orbits around the Sun, allowing the journey time from one to the other to be at the shorter end of a scale which sees optimal Earth-Mars transit times vary between (approx.) 180-270 days. In fact, Earth and Mars were at the time the “closest” they have been in 60,000 years, hence why NASA also chose that year to launch the twin Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission featuring the Spirit and Opportunity rovers.

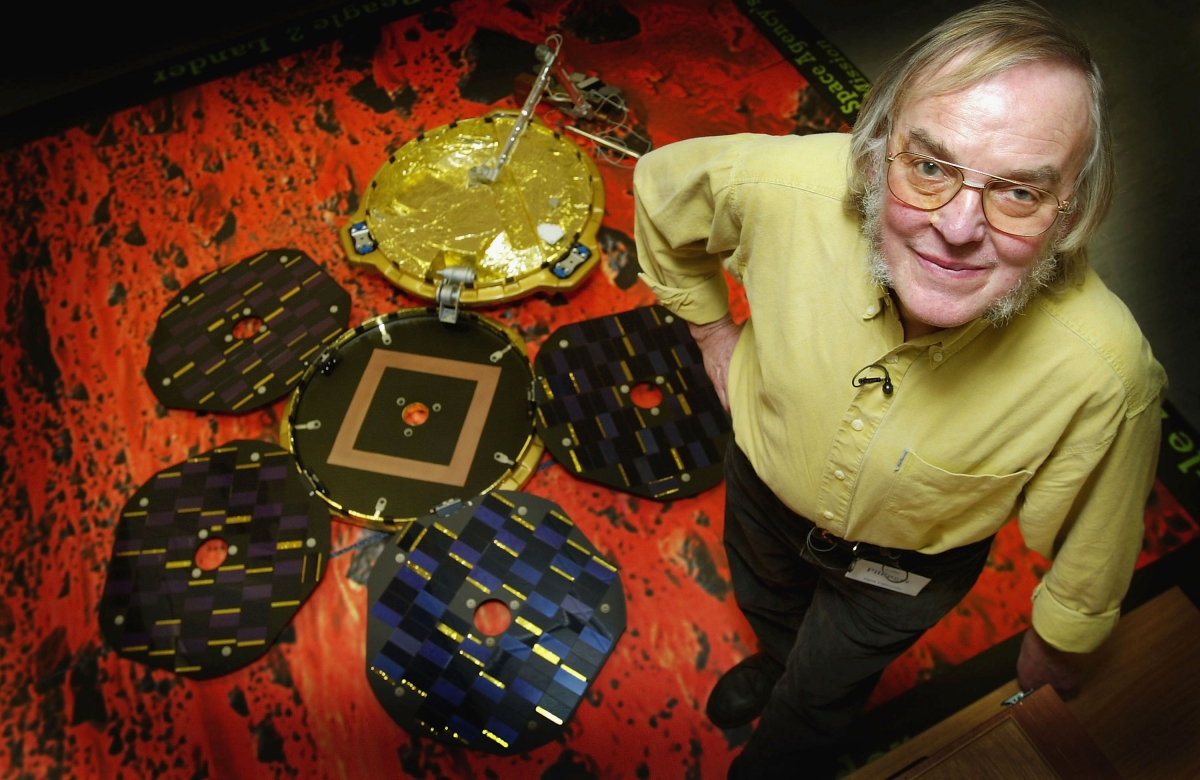

Taken as a whole, the Mars Express mission is perhaps more noted for its one aspect that “failed”: the British-built Beagle 2 lander (named for the ship that carried Charles Darwin on his famous voyage). This was a late addition to the mission, and the brainchild of the late Professor Colin Pillinger (whom I had the esteemed honour to know ); given it was effectively a “bolt on” to an established ESA mission, it was subject to extremely tight mass constraints (which tended to change as the Mars Express orbiter evolved). These constraints led to a remarkable vehicle, just a metre across and 12 cm high when folded and massing just 33 kg, yet carrying a considerable science package capable of searching for evidence of past or present microbial life on Mars.

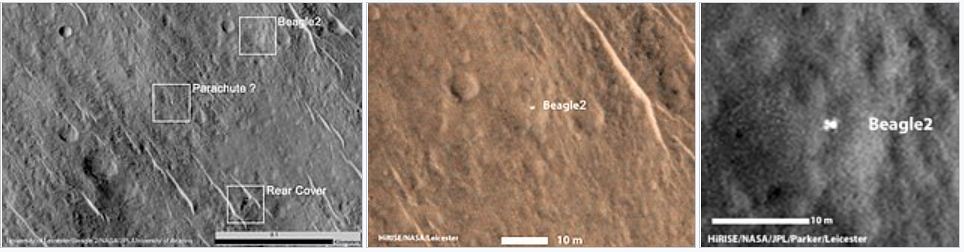

Sadly, following its separation from Mars Express on December 19th, 2003, ahead of both vehicles entering orbit around the planet and a successful passage through the upper reaches of Mars’ atmosphere, Beagle 2 never made contact following its planned arrival on the planet’s surface. For two months following the landing, repeated attempts to make contact with it were made before it was finally officially declared lost. While multiple theories were put forward as to what had happened, it wasn’t until 12 years later, in 2016 – and a year after Collin Pillinger had sadly passed away – that evidence was obtained for what appeared to have happened.

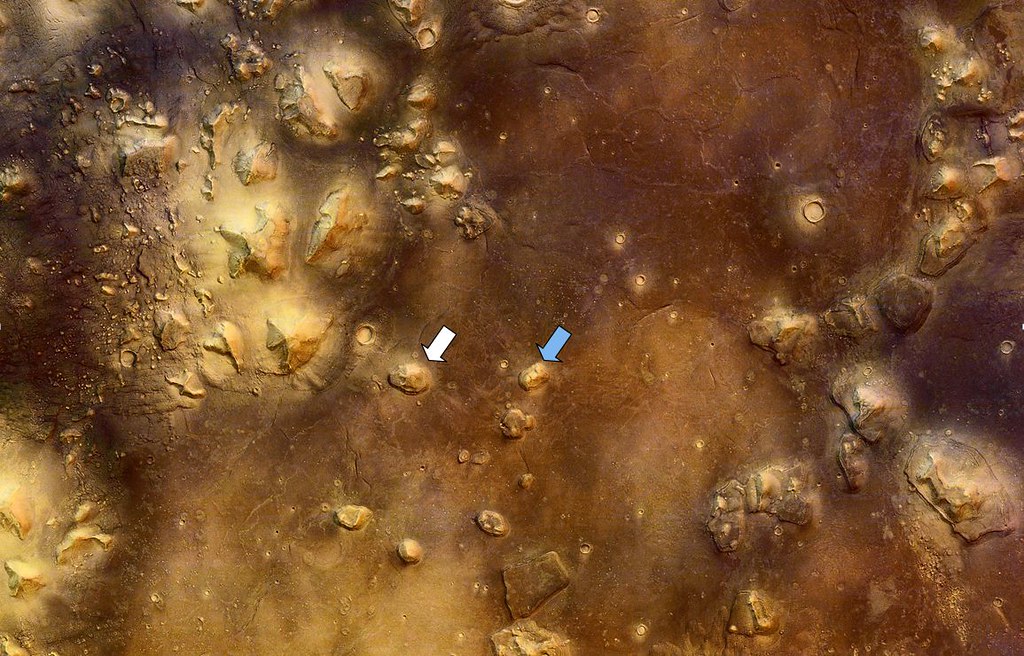

Using a technique called super-resolution restoration (SRR) on images obtained by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2015 and which appeared to show the lander intact on the surface of Mars, experts were able to enhance them to a point where they appeared to show it had in fact managed to land safely on Mars and had partially deployed its solar arrays.

The significance here is that due to its mass and size constraints, Beagle 2 was of a unique design, resembling an oversized pocket-watch and its cover. The “watch” contained the science and battery power systems, and the “cover” the communications system and flat antenna, with four round solar arrays stacked on top of it.

Following landing, Beagle 2 was supposed to fold back its “lid”, and then deploy the four arrays like petals around a flower. This would allow the arrays to recharge the lander’s batteries so it could operate for at least a Martian year, and expose the communications antenna. However, after enhancement using SRR, the NASA images appeared to show only two of the solar array petals had actually deployed; the other two remaining in their “stowed” position, blocking the lander’s communications antenna and denying it with a sufficient means to recharge its batteries.

However, there is one further element of intrigue: because it was known initial communications with Earth might be delayed – Beagle 2 was reliant on either Mars Express itself to be above the horizon post-deployment, or failing that NASA’s venerable Mars Odyssey orbiter – the lander was programmed to go into an automated science-gathering mode following landing. As the science instruments were quite possibly able to function, some of them might actually have deployed, allowing data to be recorded Solid State Mass Memory (SSMM) – data which might still be available for collection were the lander to ever be recovered by a human mission to Mars.

The mystery over the lack of contact with Beagle 2, coupled with the arrival of NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity on Mars at the start of 2004 combined to mean that Mars Express received very little attention following its arrival in its science orbit on December 25th, 2003 – and apart from occasional reporting on its findings, this has continued to be the case for the last 20 years.

Which is a shame, because in the time, Mars Express has carried out a remarkable amount of work and has been responsible for some of the most remarkable images of Mars seen from orbit. 0For example, and just as a very abbreviated list intended to outlines the diversity of the orbiter’s work, within two months of its arrival around Mars, it was able to confirm the South Polar icecap is 15% water ice (the rest being frozen CO2).

In April and June 0f 2003, the vehicle confirmed both methane and ammonia to be present in the Martian atmosphere; two important finds, as both break down rapidly in Mars’ atmosphere, as so required either a geological or biological source of renewal.

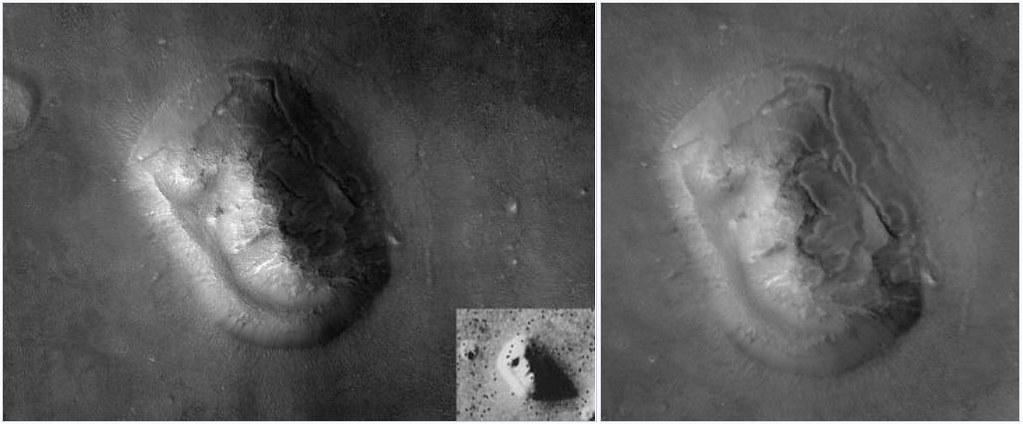

In 2006, the orbiter put another nail in the coffin of the “ancient Martians” theories which abounded following the the Viking missions in the 1970s. In one set of images of the Cydonia region of Mars taken by the orbiter vehicles, there was a was a mesa which, thanks to the fall of sunlight, and the angle at which the image was taken, appeared to give it the appearance of a “face”. This quickly spiralled into ideas the 2 km long mesa had been intentionally carved as a “message” to us, together with claims of pyramids and the ruins of a city close by.

All of this was the result of pareidolia rather than any work by ancient Martians – as evidenced by much higher resolutions of the mesa taken by NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor orbiter in 2001, and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2007 (above). Mars Express further demonstrated the effects of pareidolia in an image of Cydonia captured in 2006, which showed both the “face” mesa, and – around 50 km to the west – another which looks like a skull. While the latter mesa is also visible in some of the Viking era images, it is no way resembles a skull; the resemblance on the Mars Express image again being the result of natural influences – the fall of light, etc., – coupled with the human brain’s propensity to impose recognisable form and meaning to shapes where none actually exists.

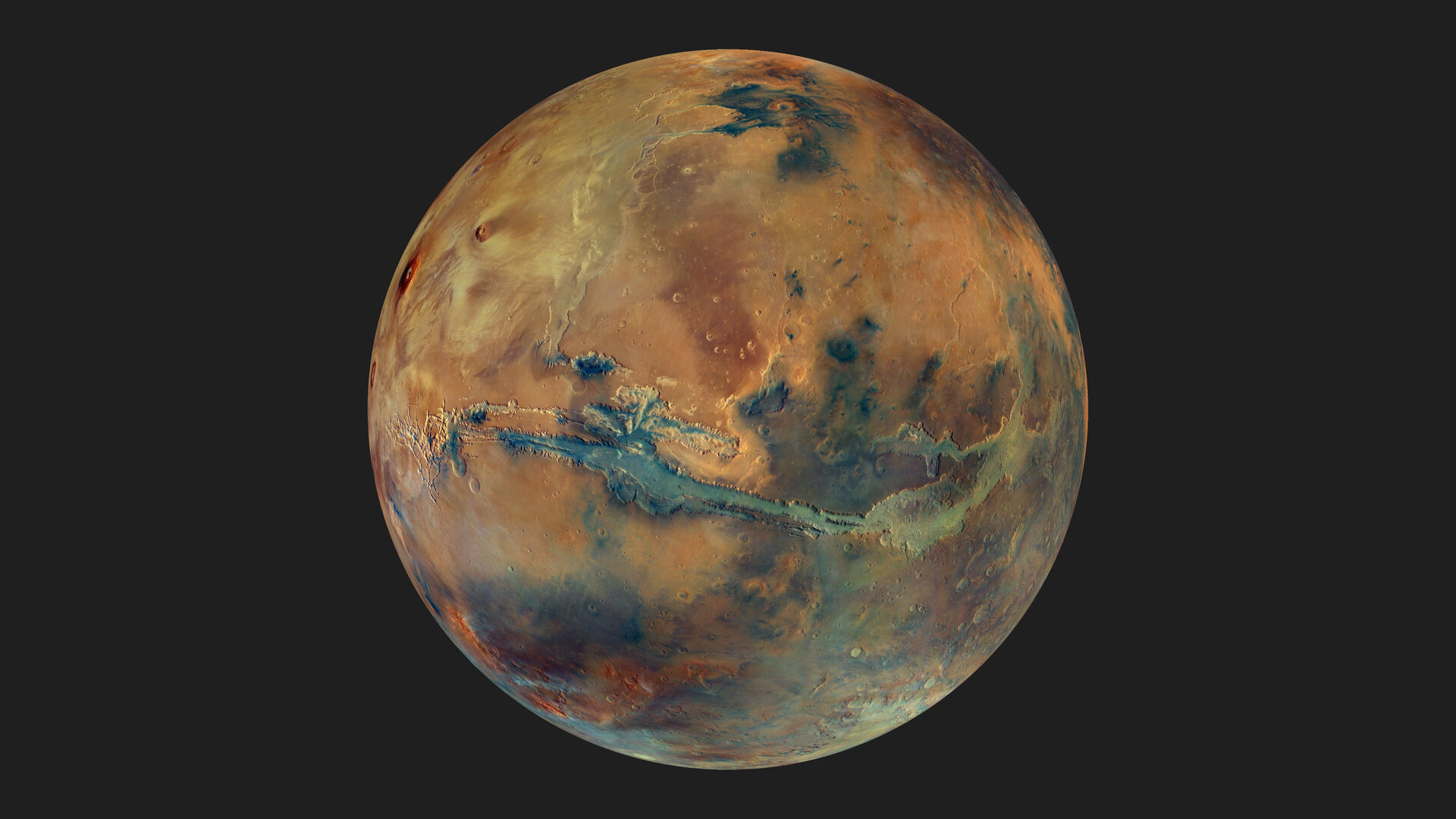

In 2009, Mars Express was able to cast an eye over Phobos, the largest and innermost of Mars’ captured moons, measuring its negligible gravity in the process, while in 2013, and as a result of its extensive work in imaging the entire surface of Mars, the orbiter was able to produce the first near-complete high-resolution map of the entire planet.

Perhaps the most significant findings by the orbiter lay with the subjects of water on Mars and the potential past habitability of the planet by microbial life. With the former, it has revealed that at least some of Mars’ water was not lost to space, but instead retreated into a number of sub-glacial lakes in the planet’s South Polar Region, lying an average 1.5 km below the surface, with the largest some 30 km in diameter.

The orbiter has also done much to map the sharp divide between the northern hemisphere lowland and southern hemisphere highlands, revealing in detail the sharp divide (the southern hemisphere is up to 3km higher in average elevation compared to the northern) between the two, and how it may have influenced the location and flow of water on Mars during warmer times.

In terms of the potential for Mars to have once supported microbial life, the findings by Mars Express were so significant in the run-up to NASA’s MSL mission with the Curiosity rover that it came very close to determining the lander point for that mission: Mawrth Vallis, rather than the selected Gale Crater.

Believed to be one of the oldest valleys on Mars, Mawrth (Welsh for “Mars”) lies on this “north / south” divide between the two hemispheres of the planet, forming a channel between the two. It is also one of the regions of Mars where there is much evidence for flooding and the repeated passage of large volumes of free-flowing water.

Mars Express has studied the region on numerous occasions, its more eccentric orbit allowing it to do so a lot easier than the NASA orbital missions. As such, it was the first mission to detect phyllosilicate (clay) minerals within the valley, and while NASA’s orbital missions have also gone on to make discoveries on the mineral clays within the area – including montmorillonite and kaolinite, alunite, and nontronite – it remains Mars Express which has enabled scientists to build up a cohesive picture as to how the valley was formed and investigate its unique distribution of clays deposited over the eons, which in turn has helped shaped the understanding of geological and climate changes on Mars and its potential to have once harboured microbial life.

More recently, the orbiter resumed studies of the valley together with Oxia Planum, a broad plain of clay-bearing rocks some 500 km south and west of Mawrth, the two locations being the finalists in the selection of a landing site ESA’s upcoming ExoMars mission featuring the rover Rosalind Franklin. Whilst Oxia was finally selected for the rover’s landing location on account of it being broader and flatter than Mawrth Valley, Mars Express continues to pay special attention to the valley as and when its orbits allow.

Originally intended for a primary mission of approximately two terrestrial years, the Mars Express mission is currently funded through until the end of 2026 – and may well continue well beyond that. Currently, the orbiter is capable of generating some 460 W of electrical power via its solar arrays, and while this is down from the 660 W available at launch, it is by no means critical, allowing the vehicle to continue to operate all its systems (even if a degree of budgeting the available power is required). Similarly, its attitude control and navigation gyros (essential for orienting and pointing the craft) all remain in good working order.

All of which means that – outside of a critical systems failure – only a mix of the remaining propellant reserves, the ability of the battery systems to continue to power the craft when it is out of direct sunlight (the batteries have lost around 50% of their capacity), and the small matter of continued funding, really stand in the way of the mission continue through until the 2030s.

So, happy anniversary, Mars Express, and here’s to many more.