After US space agency NASA indicated their schedule for the new Space Launch System (SLS) rocket is to undergo revision, with launches liable to be pushed back, the White House has stepped in with an apparent contradiction: NASA is to accelerate plans to return humans to the Moon, achieving the goal no later than 2024 – a target that requires a fully operational SLS.

The order came via an address by Vice President Mike Pence at a meeting of the National Space Council on March 26th in Huntsville, Alabama. He couched the order in terms of addressing rising concerns about delays to SLS and the “threat” of international competition. However, alternative views are that the demand is more about the Trump administration trying to achieve a Kennedy-like legacy before any possible second term for the administration has expired.

Following the address, NASA Administrator James Bridenstine backpedalled away from statement made two weeks previously, in which he indicated that NASA would look at options for initial flights of the completed Orion capsule and its European-built Service Module using commercial launch vehicles, rather than relying on the SLS, to allow more time for troublesome elements of that vehicle to be completed. Instead, NASA will now attempt to focus on getting the SLS up and running for the initial Exploration Mission flights, themselves seen as necessary precursors to a Moon landing.

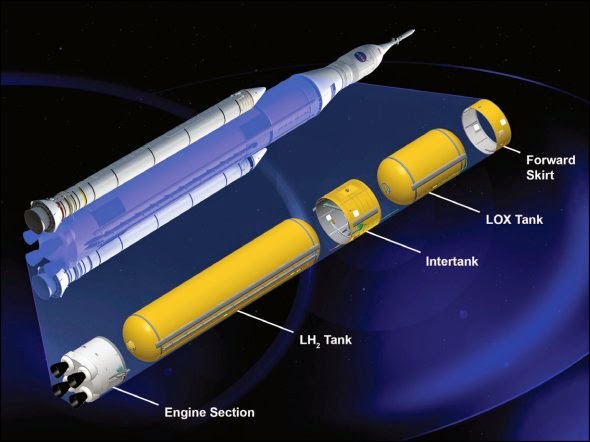

As I’ve noted in recent Space Sunday reports, there are some significant issues around the SLS core stage and its advanced Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) that has been seen as crucial to lunar operations. The issues with the latter were such that Brindenstine had indicated it would be placed on hold, and NASA would utilise the less powerful Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) at the rocket’s upper stage. Following Pence’s announcement, the NASA Adminstrator confirmed the emphasis would be back on getting the EUS completed, and a 45-day study has been initiated to determine how development of the rocket’s core stage might be accelerated.

One of the ideas for the latter that is being floated is to cut a “green run” test of the first completed core stage main engines at full power for 8 minutes, which would require the completed stage being shipped from the Michoud Assembly Facility, Louisiana, to the Stennis Space Centre, Mississippi, and instead deliver the completed stage directly to Kennedy Space Centre for integration with the rest of the vehicle for its first launch. This would cut several months from the launch schedule, but also leave the stage untested.

Bur even with such cuts, the 2024 goal is regarded as a “very aggressive goal”. To achieve it, NASA will not only have to accelerate work on the first SLS vehicle, they will need an increase in funding across multiple related projects. For example, following the first two EM launches, NASA would need to gear-up to two SLS launches a year in order to lay the groundwork for a lunar landing – including placing the initial elements of the Lunar Gateway in orbit around the Moon. This alone requires the building of a second mobile launch platform (yet to be funded by Congress).

Another issue is what will happen to the robotic precursor missions seen as stepping-stones towards a human mission. Currently, it is unlikely any of these will be ready to fly before 2021 – and no formal contracts have been awarded to the nine companies competing to fly them. Then there is the not insignificant question about the development and testing of the actual lunar lander vehicle. As such, while some organisations have responded enthusiastically to Pence’s announcement, others have sounded more cautionary notes.

Though we support the focus of this White House on deep space exploration and the sense of urgency instilled by aggressive timelines and goals, we also are cognizant of the resources that will be required to meet these objectives. Bold plans must be matched by bold resources made available in a consistent manner in order to assure successful execution.

– The Coalition for Deep Space Exploration

Even some in NASA have voiced very public misgivings against the acceleration of goals given the overall state of the SLS and supporting programmes.

Do you want to kill astronauts? Because this is how you kill astronauts. There’s no reason to accelerate going to the Moon by four years. It’s ridiculous.

– Holly Griffith Orion Vehicle Systems Engineer, speaking to AFP.

Certainly, if NASA is to meet a 2024 target date, it will need something of an increase in funding – and this is where Pence’s words fall flat: For 2020, the Trump Administration is seeking to decrease NASA’s budget by half a billion dollars compared to 2019 actual budget – and actually seek to decrease spending on SLS by 17.4% compared to 2019.

WFIRST on the Chopping Block. Again

Another programme hit by the Trump 2020 NASA budget proposal is the astrophysics flagship mission, the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST).

As I’ve previously noted in these updates, the Trump Administration tried to cancel WFIRST in their 2019 budget proposal, citing in part its expense – this despite the mission being one of the most cost-effective on NASA’s books, given it is able to use a lot of parts developed as back-ups to the Hubble Space Telescope – including the 2.4 metre diameter primary mirror.

A second reason for the 2019 cancellation – which was prevented by Congress – was a claim that WFIRST “duplicated” work to be undertaken by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and other aspects of the WFIRST mission could be achieved via “cheaper” means. In actual fact, WFIRST and JWST are able to mutually support one another’s mission, rather than duplicating mission elements. Nevertheless, it is the ongoing delays with JWST which are now being pointed to as the reason to de-fund WFIRST, the argument being that until JWST is launched, WFIRST isn’t a priority.

NASA Administrator Brindenstine has suggested WFIRST’s funding could be brought back up to speed once JWST has been deployed. The problem here is that once a project has been de-funded, it can be very difficult to revive, as doing so tend to foreshorten desired time frames in order to get a mission launched, resulting in much larger additional costs than might have been the case had funding been allowed to continue through the intervening years. Further, 2020 is a crucial year from WFIRST: a design review for the overall mission is scheduled for October, and is due to be followed by what is called “Key Decision Point C”, and formal mission confirmation. Without funding, these milestones cannot be reached, potentially leaving the project in an uncomfortable limbo.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: rockets, planets and Martian helicopters”