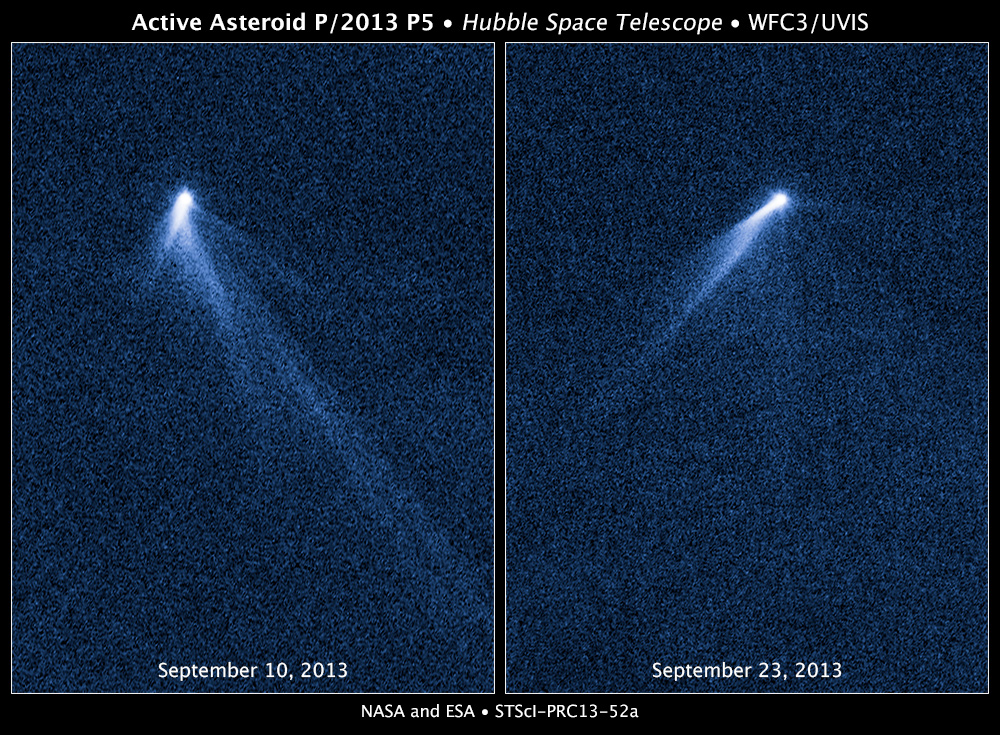

The solar system is welcoming its third (known at least – we have no idea how many may have passed through the solar system undetected down the ages) interstellar visitor. 3I/ATLAS, also known as C/2025 N1 (ATLAS), was identified on July 1st, 2025 as an interstellar comet. It is the third such object positively identified as having interstellar origins to pass through the solar system in the last eight years, the others being 1I/ʻOumuamua (discovered in October 2017) and 2I/Borisov (discovered in August 2019).

At the time of its discovery, 3I/ATLAS was some 4.5 AU (670 million km) from the Sun and moving at a relative speed of 61 km/s (38 m/s). It’s exact size is unknown, as it is behaving as an active comet and so is surrounded by a cloud of reflective gas and vapour. However, estimates put it to be somewhere between around 1 km and 24 km across – with its size likely to be at the lower end of this scale.

The object was located by the NASA-funded ATLAS survey telescope at Río Hurtado, Chile, and will reach perihelion in October 2025, when it will pass around the Sun at a distance of 1.3 AU. Following its initial discovery as a object moving through the inner solar system, there were concerns it would come close to Earth – and it was even designated a Near-Earth Object (NEO). However, checks back through the records of other observatories which may have spotted the object – such as the Zwicky Transient Facility – indicated 3I/ATLAS had been observed in mid-June 2025. These observations and those made by ATLAS confirmed the object to be of interstellar origin and on a hyperbolic path through the solar system that would not bring it close to Earth.

More recently, studies of the object’s track suggest that Comet 3I/ATLAS may pre-date the formation of our solar system by over three billion years, and that it appears to hail from the outer thick disk of the Milky Way, rather than the inner disk where stars like our Sun typically reside. The thick disk is where the majority of the Milky Way’s oldest stars tend to reside, and it is likely 3I/ATLAS originate in one of these ancient star systems.

Given spectrographic analysis of the object is rich in water ice, making it the oldest and most unique of our three known interstellar visitors to date. This water ice means that the comet is likely to become more active and reveal more about itself as it approaches and passes around the Sun and becomes more active. Observations will be curtailed as it passes around the Sun relative to Earth, but then resume as 3I/ATLAS starts its long journey back out of the solar system and back to interstellar space.

New Glenn to Launch EscaPADE on Second Flight

Blue Origin has confirmed that the second flight of its massive New Glenn launch vehicle will be to launch NASA’s Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorer (EscaPADE) mission to Mars and the launch is scheduled for mid-to-late August 2025.

This mission had actually be scheduled to fly aboard New Glenn’s inaugural launch in late 2024; however, NASA withdrew it from the launch manifest in September 2024 when it became clear Blue Origin would be unlikely to meet the necessary launch window for the mission, so as to avoid the expense (and complications) of loading the necessary propellants aboard the EscaPADE vehicles and then having to off-load them again.

Since then, it has been unclear when the EscaPADE mission would launch – or on what vehicle. Speculation had been that the second launch of New Glenn – originally (and provisionally) scheduled for spring 2025 – could be used to send the mission on its way; However, this was not confirmed by either NASA or Blue Origin until the latter issued as formal confirmation on July 17th announcement.

EscaPADE is a pair of small satellites called Blue and Gold led by UC Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory, with the two craft built by Rocket Lab Inc., and financed under NASA’s Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx) programme. The mission has three primary mission goals:

- Understand the processes controlling the structure of Mars’ hybrid magnetosphere and how it guides ion flows

- Understand how energy and momentum are transported from the solar wind through Mars’ magnetosphere

- Understand the processes controlling the flow of energy and matter into and out of the collisional atmosphere.

Each of the two satellites carries the same three science experiments to achieve these goals. Due to the relative positions of Earth and Mars at the time of launch, the craft will not be able to enter into a direct transfer orbit. Instead, they will initially target the Earth-Sun Lagrange 2 position (located on the opposite side of Earth’s orbit around the Sun relative to the latter), where they will loiter for several months carrying out solar weather observations. As a suitable transfer orbit from the L2 position opens, so the satellites will continue their journey, with a total transit time from Earth to Mars of around 24 months.

On initial arrival around Mars, Blue and Gold will enter a highly elliptical orbit that will be gradually lowered and circularised over a 6-month period, after which the science mission proper will begin. Both vehicles will then occupy the same nominal orbit whilst maintaining a good separation. After this, Blue will lower its apoapsis to 7,000 km and Gold will increase its own to 10,000 km, allowing simultaneous measurements of distant parts of the Mars magnetosphere for a period of some 5 months, after which the primary mission is due to end.

As well as EscaPADE, the New Glenn NG-2 launch will also fly a technology demonstration for commercial satellite company Viasat in support of NASA Space Operations Mission Directorate’s Communications Services Project, with the mission serving as the formal second certification flight to clear New Glenn to fly US national security missions. As with the first flight of the vehicle, Blue Origin will attempt to have the first stage of the booster for landing on the company’s floating landing platform Jacklyn.

AX-4 Crew Return to Earth

In my previous Space Sunday, I wrote about the Axiom Ax-4 private mission to the International Space Station (ISS). Well, two weeks have passed and the 4-person crew is back on Earth. The mission had been scheduled for a minimum of 14 days and – as I’ve reported – the mission was subjected to a series of delays prior to launch.

As such, it was perhaps somewhat fitting the crew’s return was slightly delayed, with Grace, their SpaceX Crew Dragon, departing the space station at 11:15 UTC on July 14th, to commence a gentle return to Earth over a period of almost 24 hours, splashing down off the coast of California on July 15th.

The slow return was in part to allow a Pacific splash-down, avoiding the need for the Crew Dragon to re-enter the atmosphere over the US mainland, as would be required were the vehicle to make a splash-down in the Atlantic, as has been the case with the majority of past Crew Dragon missions. The reason for this is that there have been several occasions where pieces of a Dragon “Trunk”- the service module – surviving re-entry into the atmosphere to come down close to – or within – populated areas.

In all the international crew spent two and a half weeks on the ISS carrying out some 60 experiments and technology demonstrations which involving 31 different nations, and also carried out a series of public outreach events. The mission went a long way towards increasing Axiom’s experience in on-orbit operations ahead of plans for the company to start operating its own station as the ISS reaches its end-of-life.

This mission marked the first time in space for the three male members of the crew – Shubhanshu “Shux” Shukla from India; Tibor Kapu, a member of HUNOR, Hungary’s orbital astronaut programme which operates independently of Hungary’s involvement with the European Space Agency (ESA); and Sławosz “Suave” Uznański-Wiśniewski, from Poland, who is an ESA astronaut. It also marked mission Commander Peggy Whitson, a former NASA astronaut and now Axiom’s director of human spaceflight, extending her record for cumulative days spent by an American in space to 69 days across five missions.

Starliner Flight: 2026, and No Crew

As Boeing and NASA continue to work on the problems affecting the former’s CST-100 Starliner crew vehicle, the US space agency has indicated that, despites hope to slot a possible re-flight for Starliner into 2025, the next mission will almost certainly not come before 2026 – and is likely to be uncrewed.

Starliner’s last mission was the first to fly with a crew aboard, after two previous uncrewed test flights. However, despite the overall success of that first crewed flight, the Starliner vehicle had a series of issues with its thrusters systems which, whilst not critical, caused NASA to opt to instruct Boeing to return the vehicle – comprising the capsule Calypso and its service module (which mounted the problematic thrusters systems) – under automated means; leading to the inevitable (and largely inaccurate) claims that the crew – Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams – were “stranded” in space and in need of “rescue”.

The core issue with the vehicle’s thrusters has been identified as a design flaw with seals within the vehicle’s fuel lines and helium purge systems, which NASA and Boeing are now working to resolve. Part of the problem here is related to the fact that the vehicle’s multiple thrusters are grouped into four close-knit sets set equidistantly around the circumference of the vehicle’s service module, in what are called “doghouses”. These units experienced unexpected temperature spikes during the 2024 Crewed Flight Test, exacerbating the issues with the seals on the thrusters failing / causing valves to stick.

The doghouse system has already seen a number of improvements since the Crew Flight Test, and the focus is now on developing seals in the thruster system valves so they can better hand the stresses and remaining heat issues. This work means that no Starliner vehicle will be ready for a 2025 launch. Further, such is the schedule for 2026 ISS missions that slotting a crewed test of Starliner in that year is liable to be difficult. NASA are therefore looking to conduct a further uncrewed flight – but rather than it be merely a flight test, the plan is to have the vehicle fly cargo to the ISS, making it an “operational” mission.

.jpg)