It’s been a hectic 48 hours. On Wednesday, November 12th, after 10 years in space, travelling aboard its parent vehicle, Rosetta, the little lander Philae touched down on the surface of comet 67P/C-G/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (67P/C-G). It was the climax of an amazing space mission spanning two decades – and yet was to be just the beginning. Packed with instruments, it was hoped that Philae would immediately commence around 60 hours of intense scientific investigation, prior to its batteries discharging, causing it to switch to a solar-powered battery system.

Unfortunately, things haven’t quite worked out that way. As I’ve previously reported, the is very little in the way of gravity on the comet, so in order for Philae to avoid bouncing off of it when landing, several things had to happen the moment it touched the comet’s surface. As it turned out, two of these things didn’t happen, with the result that the lander did bounce – twice.

The first time it rose to around 1 kilometre above the comet before descending once more in a bounce lasting and hour and fifty minutes, the second time it bounced for just seven minutes. Even so, both of these bounces meant the lander eventually came to rest about a kilometre away from its intended landing zone. What’s worse, rather than touching down in an area where it would received around 6-7 hours of sunlight a “day” as the comet tumbles through space, it arrived in an area where it was only receiving around 80-90 minutes of sunlight – meaning that it would be almost impossible to charge the solar-powered battery system.

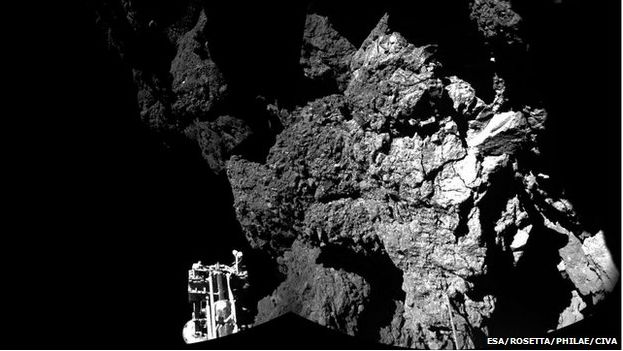

As noted above, the mission was designed so that most of the core science could be carried out in the first 60 hours of the mission, just in case something like this occurred. Even so, in order to prolong the life of the vehicle, it would have been nice to move it into a greater area of sunlight. A means of doing this had also been built-in to Philae: the three landing legs can be flexed, allowing it to “hop”. But as images were returned to Earth by the Lander, it became apparent that one of the legs is not in contact with the ground, making such a hop problematic. After discussion, it was decided not to attempt to move the lander, but focus on trying to achieve the planned science objectives.

As it turned out, the initial contact between the lander and the comet confused several of Philae’s instruments into “thinking” it had in fact landed, causing them to activate. These included the ROMAP magnetic field analyser, the MUPUS thermal mapper, the CONSERT radio sounding experiment and the SESAME sensors in the landing gear. Data received from these instruments, arriving on Earth some 30 minutes after initial contact with the comet, and the information which followed, help alert mission staff that something had gone wrong, and enabled them to subsequently piece together the events that occurred during the landing sequence, while the instruments continued to gather data and transmit it back to Earth via Rosetta.

On Friday, November 14th, the decision was taken to activate Philae’s sample-gathering drill, officially referred to as SD2. This had been postponed from the previous day, as the drill uses a lot of power. However, obtaining and analysing samples from inside the comet is a central part of the mission, the decision was made to push ahead with drilling operations.