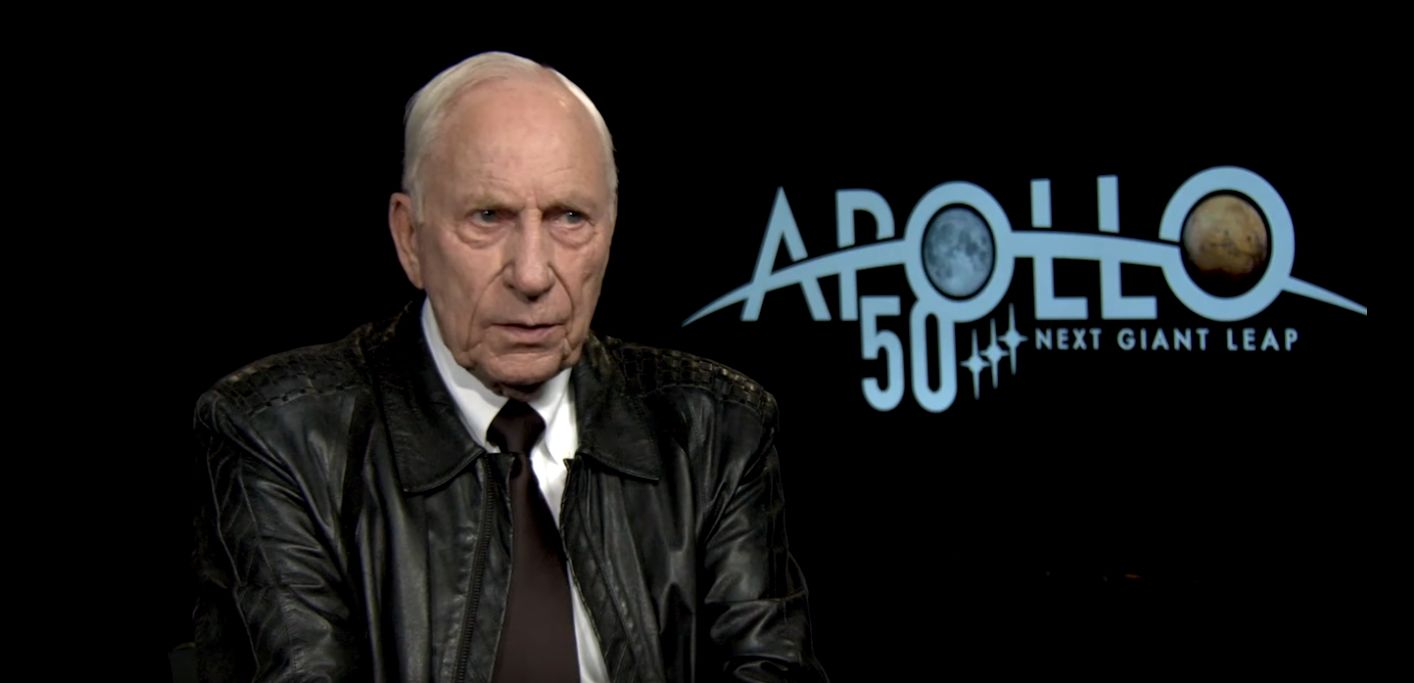

On Friday, August 8th, NASA confirmed the passing of James A. Lovell, who alongside the crew of Apollo 11, could well be the most famous of the Apollo astronauts. During his career at NASA he flew into space fours times and to the Moon twice – although he was destined to never set foot on the latter, despite being a mission commander.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio on March 25th, 1928, James Arthur Lovell Jr., was the only child of James Lovell Snr., a Canadian expatriate, and Blanche Lovell (née Masek), who was of Czech descent. Following the death of his father in a car accident in 1933, James and his mother moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he developed an interest in aircraft and rocketry as a teenager. After graduating high school, Lovell enrolled in the US Navy’s “Flying Midshipman” programme, which enabled him to attend the University of Wisconsin and study engineering – something he could not otherwise have been able to afford. As his Navy stipend was fairly meagre, he supplemented his income working a local restaurant as a busboy and wishing dishes.

In 1948, Lovell’s hoped-for career as a potential naval aviator almost came to an end when the Navy announced it was cutting back on the number of students being accepted through the “Flying Midshipman” programme. However, with the aid of local Congressman John C. Brophy, Lovell was able to turn this downturn in his career into a positive, by being accepted into the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, where he was able to both continue his studies and secure himself a US Navy commission upon his graduation.

This happened in 1952, with Lovell gaining a Bachelor of Science degree and a US Navy commission as an ensign. He was then selected for aviation training. However, prior to commencing flight training, he married his long-term sweetheart, Marilyn Lillie Gerlach, who had transferred to George Washington University in Washington, D.C., so she could be near him while he was at Annapolis.

In February 1954, Lovell completed his flight training and was assigned as a night fighter pilot operating out of Virginia, prior to being moved to the aircraft carrier USS Shangri-La during her third commissioning as US Navy fleet carrier. Sailing in the western Pacific and completing 107 carrier sorties, Lovell was again reassigned in 1956, this time to provide transition training for pilots moving over to the new generation of Navy jets entering service.

This work qualified Lovell for selection as a trainee test pilot in 1958, and he joined a class with included future fellow astronauts Walter “Wally” Schirra Jr and Charles “Pete” Conrad Jr. After six months of training, Lovell graduated at the top of the class – which should have assured him a role as a test pilot. Instead, he found himself pushed into Electronics Testing, and assigned to work on airborne radar systems.

This prompted him to join Schirra and Conrad in applying to join NASA’s first astronaut intake, the three being part of a batch of 110 test pilots initially selected for consideration as potential astronauts. Ultimately, Schirra was the only one of the three to be selected to become one of the Group One Mercury Seven astronauts; Conrad blew his chances by rebelling against a number of the psychological tests, finding them objectionable, whilst Lovell missed out when a temporarily high bilirubin count stopped his selection.

Returning to naval duties, Lovell became the Navy’s McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II programme manager, followed by a stint as a flight instructor and a safety engineering officer. Then in 1962, NASA started the selection process for the Group Two astronaut intake (the so-called “New Nine”, as the media would eventually dub the nine selected by NASA). Both Lovell and Conrad re-applied, the latter a lot more contrite this time around, together with John Young, who had served under Lovell on the F-4 Phantom 2 programme.

Lovell was informed he has been selected as one of the “New Nine” in September 1962. The following month, he and his family moved to the Clear Lake City area near Houston, Texas, where the new Manned Spaceflight Centre was being built.

Following initial training, carried out alongside the original Mercury Seven, Lovell was selected as backup pilot for the Gemini 4 mission, with Frank Borman, another of the “New Nine” selected as backup commander. This placed Borman and Lovell in line to fly the Gemini 7 mission as the prime crew.

Gemini 7 launched on December 4th, 1965, and would become the longest space mission undertaken until Soyuz 9 in 1970. In all, Gemini 7 lasted 14 days and completed 206 orbits of Earth. It was primarily intended to solve some of the problems of long-duration space flight, such as stowage of waste and testing a new lightweight spacesuit which might be used for both Gemini and Apollo, but which both men found to be impractical.

One significant “late change” to the mission came in the last two months prior to launch. Gemini 6, with “Wally” Schirra and Thomas Stafford, had been planned to take place in October 1965. The goal of that mission was to perform a series of dockings with an Agena target vehicle. However the mission was scrubbed when the Agena for the mission suffered a catastrophic failure following separation from its launch booster, destroying itself. As a result, Gemini 6 was initially cancelled.

However, such was the importance of on-orbit rendezvous and docking to the Apollo programme, the decision was made to re-designate Gemini 6 as Gemini 6A, and launch it eight days after Gemini 7. This allowed Schirra and Stafford to perform an on-orbit rendezvous (but no docking) with Gemini 7, that latter remaining a passive target for Gemini 6A whilst Schirra and Stafford manoeuvred their vehicle.

Following their launch, Borman Lovell performed their own rendezvous manoeuvre: following separation from their Titan II launch vehicle, Borman turned their craft around and flew in formation with the expended Titan II for fifteen minutes before moving away to start their mission proper. This included each man having the opportunity to doff his spacesuit and test working in shirt sleeves in the vehicle, and then donning it in a space little bigger than the front seat of a car. These tests greatly contributed to Apollo crews being able to fly to the Moon and back in their shirt sleeves, only wearing their pressure suits during critical phases of the mission, Lovell and Borman finding the revised Gemini spacesuit cumbersome, and long-term work inside a spacecraft whilst wearing a pressure suit too restrictive and uncomfortable.

The rendezvous with Gemini 6A took place on December 15th, 1965, same day as Gemini 6A launched. At the time, Gemini 7 was “parked” in a circular 300 km orbit, allowing Gemini 6A to “chase” it, with Schirra allowing his vehicle’s autopilot to carry out some of the manoeuvring before taking over and bringing Gemini 6A to some 40 metres separation from Gemini 7. For the next 270 minutes Gemini 6A performed a series of rendezvous manoeuvres with Borman and Lovell, sometimes coming as close as 30 centimetres (1 foot) of Gemini 7. Station keeping between the two craft was so good that during one such manoeuvre, Gemini 6A was able to remain in place alongside Gemini 7 for 20 minutes with any need for control inputs.

Following completion of these tests, Gemini 6A returned to Earth the day after its launch. Gemini 7, meanwhile, continued on what Borman and Lovell would later describe as the “boring” part of the mission, prior to re-entry, splashdown and recovery on December 18th.

Gemini 7 set Lovell up to command the final Gemini mission in the programme, Gemini 12, with one Edwin E “Buzz” Aldrin Jr., as his pilot. Lovell would later describe the mission as being a means to “catch all those items that were not caught on previous flights.” One of these was to need to carry out a series of EVA tests – with Aldrin, as pilot, selected to leave the confines of the vehicle’s cramped cabin and carry them out.

Similar EVAs had been attempted in other Gemini flights, but none had really succeeded for a variety of reasons. For Gemini 12, equipment – notably tethering restraints on the Gemini vehicle – had been greatly improved, and a new underwater training capability had been introduced, allowing Aldrin to gain familiarity with being weightless through neutral buoyancy ahead of the mission – something which would go on to be a staple of human spaceflight training at NASA.

A shorter 4-day duration mission, Gemini 12 lifted-off on November 11th, 1966. The following day Lovell and Aldrin completed a rendezvous and docking with the Agena target vehicle, launched just 1 hour and 39 minutes ahead of them. Aldrin completed a 2 hour 20 minute EVA whilst the Gemini spacecraft was docked with its Agena target vehicle, successfully meeting all of his objectives, and the two men carried out a series 14 scientific experiments prior to returning to Earth on November 16th, 1966.

Following the tragedy of the Apollo 1 fire, the Apollo Command Module went through a significant re-design, including the hatch mechanism which had effectively trapped the Apollo 1 crew in their burning vehicle, leading to their deaths. As a result, the updated vehicle had to go through a series of ground-based qualification tests. One of these tests formed Lovell’s next “mission” – spending 48 hours bobbing around the Gulf of Mexico in Command Module test article CM-007A along with Stuart Roosa and Charles Duke Jr , testing its seaworthiness, the efficiency of its floatation devices and dealing with any potential small leaks of seawater entering the vehicle.

With the Apollo programme attempting to get back on track after Apollo 1, Lovell was assigned as back-up Command Module Pilot (CMP) for Apollo 9. He was then promoted to the prime crew when Michael Collins had to be removed as prime CMP so he could receive surgery for a spinal bone spur. This move reunited Lovell with Frank Borman, Apollo 9’s commander.

Apollo 9 was intended to be the second half of a pair of missions designed the test the the Apollo Lunar Module (LM), Apollo 8 doing so in a low Earth orbit, and Apollo 9 in a high-perigee orbit. However, with work on the Lunar Module running well behind schedule, the decision was made to scrap the high-perigee test mission, and instead carry out one low orbit test flight of the Lunar Module. To achieve this, the Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 crews were swapped. The Apollo 9 crew would now fly the LM tests, delayed to allow time for the Lunar Module to be completed; Borman and his crew, as Apollo 8, would fly a mission to and around the Moon as a part of a final check-out of the Command and Service modules on long duration flights.

Launched on December 21st, 1968, Apollo 8 was a landmark mission in a number of respects:

- The first crewed flight of the Saturn V launch system.

- The first crewed mission to ever leave low Earth orbit and enter he gravitational sphere of influence of another celestial body.

- The first crewed mission to enter lunar orbit.

- The first humans to be entirely cut off from Earth as their vehicle passed around the Moon.

- The first humans ever to witness “earthrise” – the Earth rising over the limb of the Moon, something almost impossible to see from the surface of the Moon where the Earth is either above or below the horizon.

The “earthrise” phenomenon was first witnessed as Apollo 8 came around from behind the Moon at the end of its fourth orbit. All three men were busy with various observations, with Anders taking black and white photos of the lunar surface when he happened to look up, and gasp in surprise.

Oh my God, look at that picture over there! There’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty! … You got a colour film, Jim? Hand me a roll of colour, quick, would you?

– William Anders, Apollo 8, on witnessing “Earthrise” for the first time

Taking a colour film cassette from Lovell, Ander loaded it into his camera and took the picture destined to become famous the world over, later selected by Life magazine as one of its hundred photos of the 20th century.

Entering lunar orbit, and after checking the status of the spacecraft following the orbital insertion burn of the Service Module’s main engine, Lovell provided the very first close-up description of the lunar surface as seen with unaided human eyes.

The Moon is essentially grey, no colour; looks like plaster of Paris or sort of a greyish beach sand. We can see quite a bit of detail. The Sea of Fertility doesn’t stand out as well here as it does back on Earth. There’s not as much contrast between that and the surrounding craters. The craters are all rounded off. There’s quite a few of them, some of them are newer. Many of them look like—especially the round ones—look like hit by meteorites or projectiles of some sort. Langrenus is quite a huge crater; it’s got a central cone to it. The walls of the crater are terraced, about six or seven different terraces on the way down.

– Jim Lovell, Apollo 8, offering the first close-up description of the Moon

As they rounded the Moon for the ninth of ten times, on Christmas Day 1968, the crew of Apollo 8 made a second television broadcast to Earth. It concluded with each of the three men reading verses from the Book of Genesis describing the creation of the Earth; given what they had witnessed with “earthrise” the passages seemed particularly fitting.

During their trip home, the crew were informed they had presents hidden aware in their vehicle, courtesy of Chief of the Astronaut Office, Donald “Deke” Slayton: a Christmas dinner with all the trimmings, all specially packed together with a miniature bottle of brandy for each man. Borman ordered the bottles to remain sealed until after splashdown to avoid any risk of alcoholic impairment during re-entry and splashdown – all of which occurred without incident on December 27th, 1968. However, no warning was required: all three men kept the bottles unopened as keepsakes for years.

As prime crew for Apollo 8, Lovell was automatically selected as commander on the back-up crew for Apollo 11. Under the crew rotation rules established by “Deke” Slayton, this assignment in turn meant Lovell would command Apollo 14.

However, fate again intervened, as it had in so many ways during Lovell’s career. Apollo 13 was to have been commanded by Alan Shepard, marking his return to flight status after being grounded for several years. However, Slayton’s boss, George Mueller, Director of Manned Space Flight, refused to sign-off on Shepard’s selection for the mission, believing Shepard had not had sufficient training. Because of this, Slayton asked Lovell if he and his crew of Thomas Kenneth “Ken” Mattingly (who would later be replaced by John “Jack” L. Swigert Jr.) and Fred Haise Jr., would be willing to swap seats with Shepard and his crew, to give the latter more training time.

Lovell’s response to the request was to become one of the greatest unintentional understatements of the 20th Century: “Sure, why not? What could possibly be the difference between Apollo 13 and Apollo 14?”

As well all know now, Apollo 13 was to have quite a lot of difference between it and Apollo 14 – and any other Apollo mission NASA flew, becoming as it did potentially the most famous Apollo lunar mission alongside that of Apollo 11, but for very different reasons.

“We have a problem here.” – CMP Jack Swigert.

“This is Houston, say again please,” – CapCom Jack Lousma.

“Houston, we’ve had a problem,”- CDR Jim Lovell.– From the communications between the Apollo 13 command module and Mission Control, immediately following the explosion within the oxygen tanks of Apollo 13’s Service Module

The safe recovery of the Apollo 13 crew following an explosion within the Service Module’s oxygen tank 2 is the stuff of legend so much so, that rather than dwelling on it here, I’ll refer readers to my article on the occasion of its 50th anniversary –Space Sunday: Apollo 13, 50 years on.

Apollo 13’s flight trajectory would result in Lovell, Haise, and Swigert gaining the record for the farthest distance that humans have ever travelled from Earth to date. It also made Lovell one of only three Apollo astronauts, along with John Young and Eugene Cernan, to fly to the Moon twice – although unlike Cernan and Young, he was never destined to set foot on its surface. In all, he accrued 715 hours and 5 minutes in space flights on his Gemini and Apollo flights, a personal record that stood until the Skylab 3 mission in 1973.

Following his retirement from NASA in 1973, Lovell had a successful business career, taking on both CEO and President positions for a number of corporations, and serving on the board of directors of several more. In 1999, he and his family opened Lovell’s of Lake Forest, a restaurant in Lake Forest, Illinois, where the family settled. The head chef was James “Jay” Lovell, his oldest son, who took over the business in 2006, and ran it through until in closed in 2014.

Lovell and his wife Marilyn remained married through until her passing in August 2023 at the age of 93. Mount Marilyn in the Montes Secchi was named in her honour by Lovell in during the Apollo 8 mission, with the name later officially adopted. Lovell has a small crater on the lunar farside named for him.

Lovell passed away at the age of 97 at his home in Lake Forest, Illinois. He is survived by his four children, Barbara, “Jay”, Susan, and Jeffrey.