August and September 2022 mark the 45th anniversaries of the launches of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, NASA’s twin interplanetary – and now interstellar – explorers.

Designed to take advantages of a planetary alignment which occurs once every 176 years, allowing the use the gravities of one of the outer planets to “slingshot” a vehicle on to the next, the two Voyager mission vehicles remain in operation today, and continue to stand at the forefront of our understanding of the local space surrounding our solar system.

Voyager 1 continues to set records as the furthest man-made object from Earth – it is now over 23.3 billion kilometres away – whilst Voyager 2 remains famous for giving us our first detailed views of Uranus and Neptune during its 20-year voyage through the outer solar system.

Products of the 1970s, the Voyager craft stand as museum pieces by today’s standards. Each has around 23 million times less memory than a modern cellphone, their communications systems can only transmit and receive data some 38,000 times slower than a modern cellular network, and they record the data they gather on an 8-track tape recorder prior to transmitting it back to Earth. Nevertheless, the amount of knowledge they have gathered and returned to us about the outer reaches of the solar system, the heliosphere (the bubble of space around the Sun in which the solar system resides), the heliopause (the boundary between that Sun-dominated “bubble” and the galaxy at large) and the realm of interstellar space beyond that bubble.

Operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the Voyager craft were launched in reverse order, with Voyager 2 lifting-off on August 20th, 1977 and Voyager 1 following on September 5th, 1977. The reason for this ordering was simple: during the development of the mission, Saturn’s moon Titan, known to have an atmosphere, was identified as a primary target for fly-by investigation, and so was assigned to Voyager 1.

However, in order to reach the moon, the vehicle would have to follow a course that would carry it over Saturn’s northern reaches, and throw it “down” and out of the plane of the ecliptic and away from any chance of reaching the outer planets. Instead, Voyager 2 was tasked with completing the “grand tour” of the major planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, and in order to achieve this, it would have to be launched first.

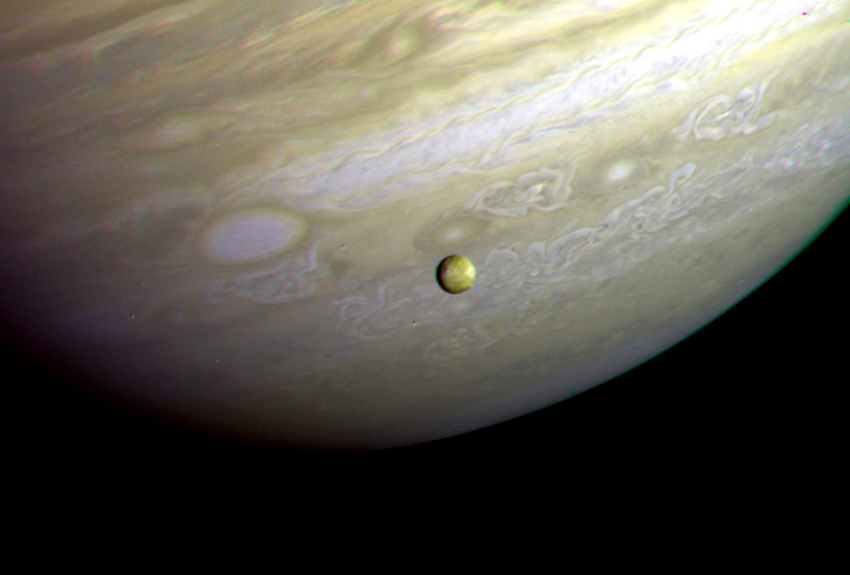

Even so, thanks to the nature of orbital mechanics requiring Voyager 2 to be thrown out on a more circular, “indirect” path towards Jupiter whilst Voyager 1 could be launched more directly towards Jupiter meant it could reach the gas giant first, arriving in January 1979, having “overtaken” Voyager 2 in December 1977. . Its passage through the Jovian system revolutionised our appreciation of the Galilean moons of the system, after which it travelled on to its November 1980 encounter with Saturn and then Titan.

Voyager 2’s more circular trajectory meant it did not reach Jupiter until July 1979, six months behind Voyager 1, but its route allowed it to make a much closer fly-by of Europa, the ice-covered Galilean moon, giving scientists the first hint of the nature of the mechanisms at work deep within the moon.

From here the vehicle journeyed on to an August 1981 encounter with Saturn and then Uranus in 1986 and then Neptune in August 1989, whilst Voyager 1 continued onwards toward the heliopause, all of which I covered in Space Sunday: Voyager at 40.

In 2010, Voyager 1 commenced a two-year transition from the space dominated by the Sun and its outward flow of radiation, and the realm of interstellar space. The first indications that it was beyond the influence of the Sun’s radiation came in later 2012 – although it was not until March 2013 that this was empirically confirmed through analysis of multiple data returned by the vehicle.

Voyager 2 commenced its voyage through the heliopause in 2013; however, as it was still travelling within the plane of the ecliptic, it was effectively travelling through a “thicker” part of the “bubble wall” of the heliosphere, so it did not enter interstellar space until November 2018.

Even so, and possibly confusingly, neither craft have actually departed the solar system per se. This is because the “size” of the solar system is measured in two ways: the influence of the Sun’s outward flow of radiation and by the influence of its. Despite having passed through the former, both craft are sill within space affected by the latter, and neither will reach the Oort Cloud – the source region of long-period comets and seen as marking the outer limits of the Sun’s gravitational influence – for another 300 years.

As such, both of the nuclear-powered vehicles are now engaged in a multi-vehicle mission (having been joined in it by the likes of the New Horizons spacecraft, the Parker Solar Probe and others) referred to as the Heliophysics Mission.

The Heliophysics Mission fleet provides invaluable insights into our Sun, from understanding the corona or the outermost part of the sun’s atmosphere, to examining the sun’s impacts throughout the solar system, including here on Earth, in our atmosphere, and on into interstellar space. Over the last 45 years, the Voyager missions have been integral in providing this knowledge and have helped change our understanding of the sun and its influence in ways no other spacecraft can.

– Nicola Fox, director of the NASA’s Heliophysics Division

Today, as both Voyagers explore interstellar space, they are providing humanity with observations of uncharted territory. This is the first time we’ve been able to directly study how a star, our sun, interacts with the particles and magnetic fields outside our heliosphere, helping scientists understand the local neighbourhood between the stars, upending some of the theories about this region, and providing key information for future missions.

– Linda Spilker, Voyager’s deputy project scientist at JPL

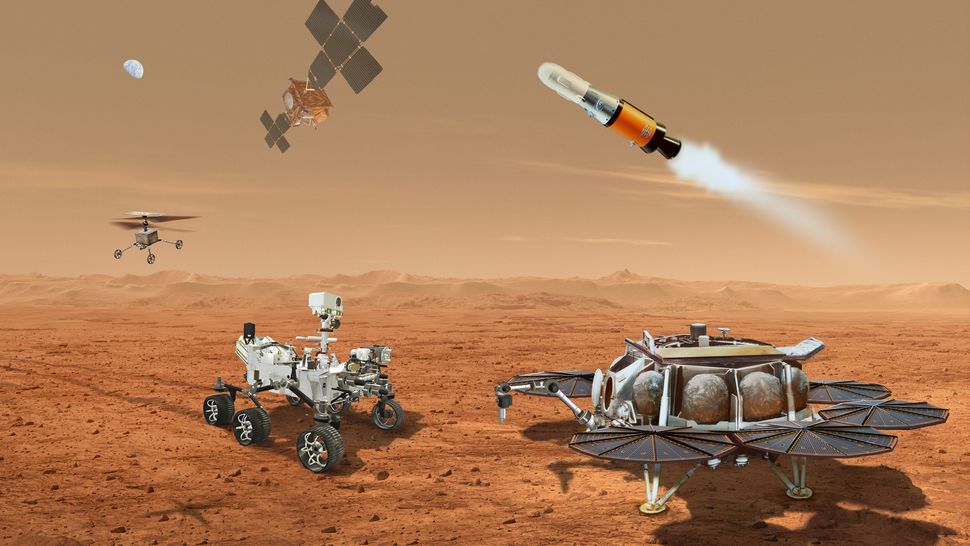

Ten years ago, on August 6th, 2012, the world held its breath as a capsule the size of a small truck slammed into the Martian atmosphere at the start of 7-minute descent referred to as the “seven minutes from hell”.

Ten years ago, on August 6th, 2012, the world held its breath as a capsule the size of a small truck slammed into the Martian atmosphere at the start of 7-minute descent referred to as the “seven minutes from hell”.