China continues to grow and expand its astronomy and space aspirations. In a series of announcements, the country has indicated its aims for Earth-based astronomy, the expansion of its space station, international co-operation and more on it plans for a presence on the Moon.

With the Tiangong station only having recently been “completed” in terms of its pressurised modules with the arrival of the Mengtian science module in October, China had originally indicated that the only remaining module awaiting delivery to the station was the Xuntian space telescope, capable of docking with the station for maintenance, but designed to operate as a free-flying automated platform to be launched in 2023.

However, Wang Xiang, director of space station systems at the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST), has indicated China is considering adding a second “core” module to Tiangong. If this goes ahead, it will be mated to the axial port of the current docking hub at the forward end of the Tinahe-1 module.

According to Wang, the new module will provide a larger and more comfortable living environment for crews, and would include its own docking hub capable of supporting two further modules as well as accepting vehicles docking at its the axial port. This would allow the station to double in size and support larger crew numbers, as well as allowing it to operate for considerably longer than the planned 10-year time frame.

In addition, CAST has announced China is working with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and other Gulf states to reach partnership agreements which could see these states working alongside China aboard Tiangong, developing a human presence on the Moon and in deep-space astronomy and robotic exploration.

Among other aspects of the agreement is the potential to establish a China-GCC (Gulf Cooperating Council – comprising Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, Bahrain, Oman, and Kuwait) joint centre for lunar exploration, which would also oversee the selection and training of tiakonauts from GCC member states.

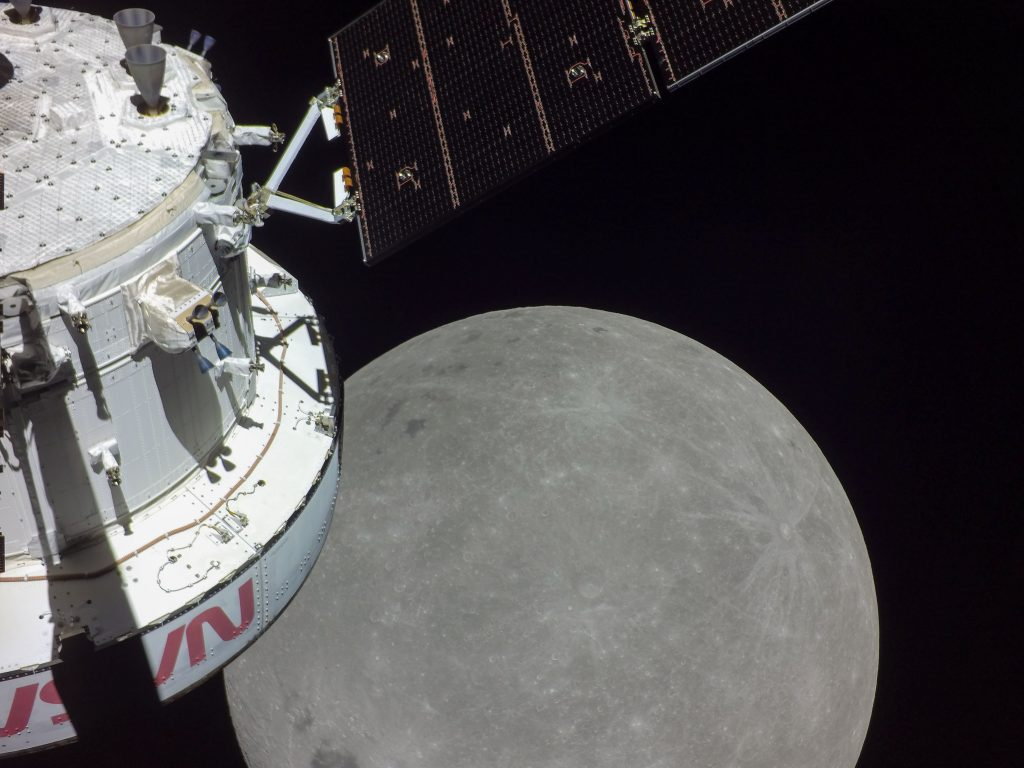

In terms of the latter, China is keen to gain international partners in its vision for lunar exploration in order to match the Artemis Accords. The latter is a set of a non-binding agreements that (to date) has seen 23 nations agree to support the US-led return to the Moon with personnel, materiel and scientific endeavours.

China’s lunar aspirations are seen by some as potentially kicking-off a new “space race”, given both it and the United States have identified the Moon’s south polar regions as the most likely location for establishing bases, given the relative accessibility of water ice within craters there. Whether this proves to be the case remains to be seen; certainly, there is a degree of chaffing within China at being excluded from all international space efforts involving the United States; however, the country has been developing its own approach to space exploration for decades without feeling the need to be seen as directly competing with the US in a manner akin to the US / Soviet space race.

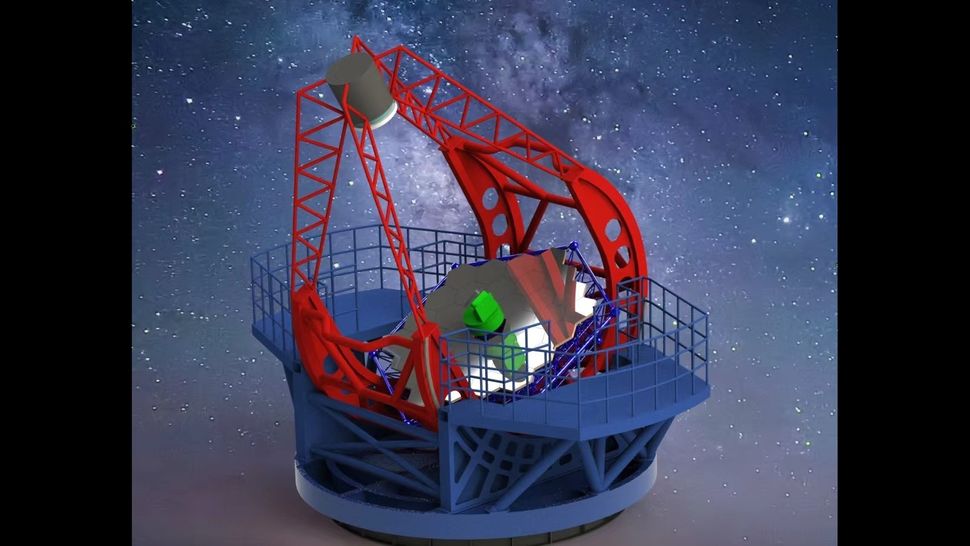

With regards to astronomy, China is also looking to build its own version of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with the first phase of the observatory being operational by 2024, and the completed facility operational by around 2030.

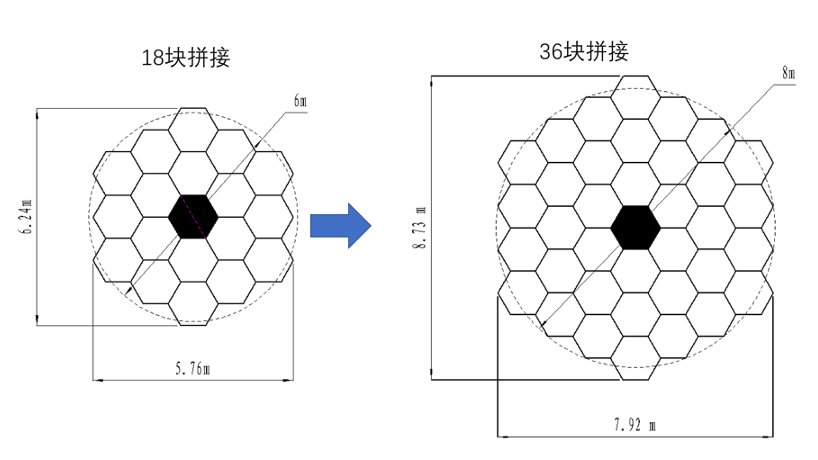

The project is to be led by the Peking University, but rather than being launched into space, this observatory will be Earth-based. Referred to as the Expanding Aperture Segmented Telescope (EAST), the observatory will have a primary mirror similar to that of JWST, a 6-metre diameter made up of 18 individual hexagonal mirrors which work both individually and collectively to focus the light they gather into the secondary mirror for transfer back into the telescope and its instruments.

The site for the observatory is Saishiteng Mountain within the Qinghai Province on the Tibetan plateau, 4.2 kilometres above sea-level, well above the majority of the denser atmosphere, making it much easier for the telescope to also compensate for the distorting influence of that atmosphere.

But that’s not all; as an Earth-based telescope, EAST will be constructed in two phases. Once the 6-metre primary mirror system has been completed, and as funding allows, the addition of a further 18 mirror segments, increasing the mirror’s diameter to almost 8 metres; 1/3 as big again as JWST.

The cost estimate for the first phase of the observatory’s construction has been put at a mere US $69 million, with the expansion work – to be completed by 2030, as noted, to cost around a further US $20 million, compared to JWST’s estimated US $9 billion construction cost – although in fairness, EAST is an optical, rather than infra-red telescope, and so doesn’t require the need to operate at extremely lower temperatures, making it a lot less complex. When completed, EAST will be the largest optical telescope in the eastern hemisphere.

NASA Issues RFI Regarding Hubble Reboost

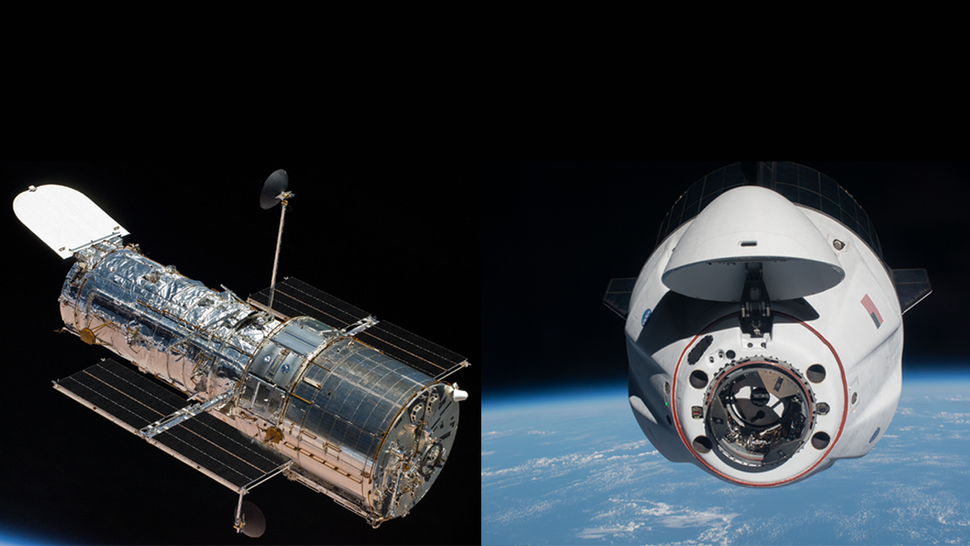

Since its launch in to a 540 km orbit above Earth in 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) has required regular “reboosting” as drag caused by friction contact with the tenuous upper atmosphere caused its orbit to decay. Up until 2009, these operations were completed by the US space shuttle as a part of scheduled HST servicing missions, with the very last mission serving to push HST to its highest orbit in anticipation of the shuttle being retired from active duty in 2011.

However, since then, atmospheric drag has reduced its orbit by some 60 km, and unless countered, it will force NASA to de-orbit HST in 2029/30 to ensure it burns-up safely and any surviving debris falls into the Pacific Ocean. By contrast, a re-boost mission could extend Hubble’s operational life by another 20 years.

To this end, in September 2022, SpaceX and billionaire Jared Isaacman – who has already funded one private mission to space using a Crew Dragon vehicle (Inspiration4) and is currently planning a further series of flights under the Polaris mission banner – started work on an unofficial mission outline to rendezvous with HST and then boost its orbit. NASA then joined in these discussions on a non-exclusive basis or commitment to manage any reboost mission.

On December 22nd, NASA issued a formal request for information (RFI) based on those discussions and exercising their non-exclusive nature to invite any interested parties to propose how a reboost mission might be completed, whether or not it expressly uses SpaceX hardware or some other, likely automated, booster vehicle. The RFI period is short, closing on January 24th, 2023, and the information gathered from respondents will be assessed over a further 6-month period and alongside the SpaceX / Polaris study to determine the best means of carrying out such a mission.

In this, there are both challenges and opportunities: HST is primarily designed to be serviced by shuttle, so by default it does have the capability to dock with the likes of SpaceX Dragon or other craft without the risk of damage. However, during the 2009 servicing mission, it was equipped with a Soft Capture Mechanism (SCM), a device primarily designed to allow a small automated vehicle attach itself to Hubble as part of a de-orbit mission. But with a suitable adapter, it might be used by a vehicle the size of Dragon to safely mate with HST and then ease it to a higher orbit.

Soyuz MS-22 Leak Update

The Russian space agency, Roscosmos, has stated it will conclude its investigation in to the status of Soyuz MS-22 towards the end of January 2023.

As I’ve reported in recent Space Sunday updates, the vehicle was used to carry cosmonauts Sergey Prokopyev and Dmitry Petelin and NASA astronaut Francisco Rubio up to the ISS in September 2022, where it has been docked ever since. However, on December 14th, 2022, the vehicle suffered an extensive ammonia coolant leak, potentially crippling it.

The exact cause of the leak has yet to be determined, although Roscosmos remains convinced it was the result of either meteor dust or a tiny piece of space debris impacting the Soyuz coolant radiator, puncturing it. However, their focus has not been on determining the cause of the leak, but in trying to determine whether or not the vehicle is capable of returning the three crew to Earth safely, or if a replacement vehicle will be required.

As I noted in my previous Space Sunday update, should Roscosmos decide a replacement vehicle is required to return Prokopyev, Petelin and Rubio to Earth, it will likely be Soyuz MS-23, which would be launched in February 2023 to make an automated rendezvous with the space station. However, it is now being reported that NASA has also contacted SpaceX to assess the feasibility of using Crew Dragon to return some or all of the MS-22 crew to Earth.

In this, it is unclear as to precisely what NASA has requested of SpaceX, and neither party is commenting. One theory is that the request is to determine whether the current Crew Dragon vehicle currently docked at ISS could carry additional personnel to Earth, if required. Another is NASA wishes to access the potential of launching an uncrewed Dragon to the station as a means to act as an emergency back-up for evacuation of the station – should it be required – prior to MS-23 being available to launch.

Both options are long-shots; getting Crew Dragon vehicle and its Falcon 9 rocket ready for launch in advance of MS-23 – a mission already in preparation, regardless of whether it flies with its planned crewed or uncrewed – is not an easy task. Further Dragon isn’t equipped to handle Russian space suits, the kind used by Prokopyev, Petelin and Rubio. As such, to even consider Crew Dragon as temporary lifeboat – much less a replacement for MS-23 to bring the three crew back to Earth – would require not small modification to its support systems. Similarly, while the Crew 5 vehicle might be able to return one or two of the MS-22 crew to Earth should it be necessary to do so, there is also the no insignificant matter of getting its life support systems to work with the Russian space suits.

One particular area of concern is that a number of experts outside of NASA / Roscosmos have opined that whatever Roscosmos may announce at the end of January, MS-22 is unlikely to be safe to bring its crew home. Therefore, should Roscosmos opt to do so, NASA might opt to look to other means to return astronaut Rubio to Earth as a matter of safety.