International work on near-Earth asteroid detection systems is again ramping up as, coincidentally, a very small asteroid caused a stir in northern Europe and the UK.

2023 CX1 (originally known as Star2667 prior to its impact) was broadly similar in nature to the type of object such systems would attempt to seek out, in that it was entirely unknown to astronomers the world over until a mere seven hours before it entered Earth’s atmosphere on February 13th, 2023. Fortunately, it was small enough and light enough – estimated to be around 1 metre across its largest dimension and weighing about 1 kilogramme – to pose no direct threat, although its demise was seen from France, the southern UK, Belgium, The Netherlands and northern Spain.

Thus far, over 30,600 asteroids and comets of various classes have been identified as having some risk of striking Earth’s atmosphere, with around 8% know to be of a size (+100m across) large enough to result in significant regional damage should it to so. However, even asteroids and comet fragments of just 20-40m across could cause considerable damage / loss of life were one to explode in the atmosphere over a population centre, whilst the total number of potential threats remains unknown.

A major problem in identifying these objects from Earth’s surface using visual or infra-red means is that the Sun tends to sharply limit where and when we can look for them, whilst radar has to be able to work around 150,000 satellites and all debris and junk we have put in orbit (excluding military satellites and “constellations” of small satellites such as SpaceX Starlink and OneWeb).

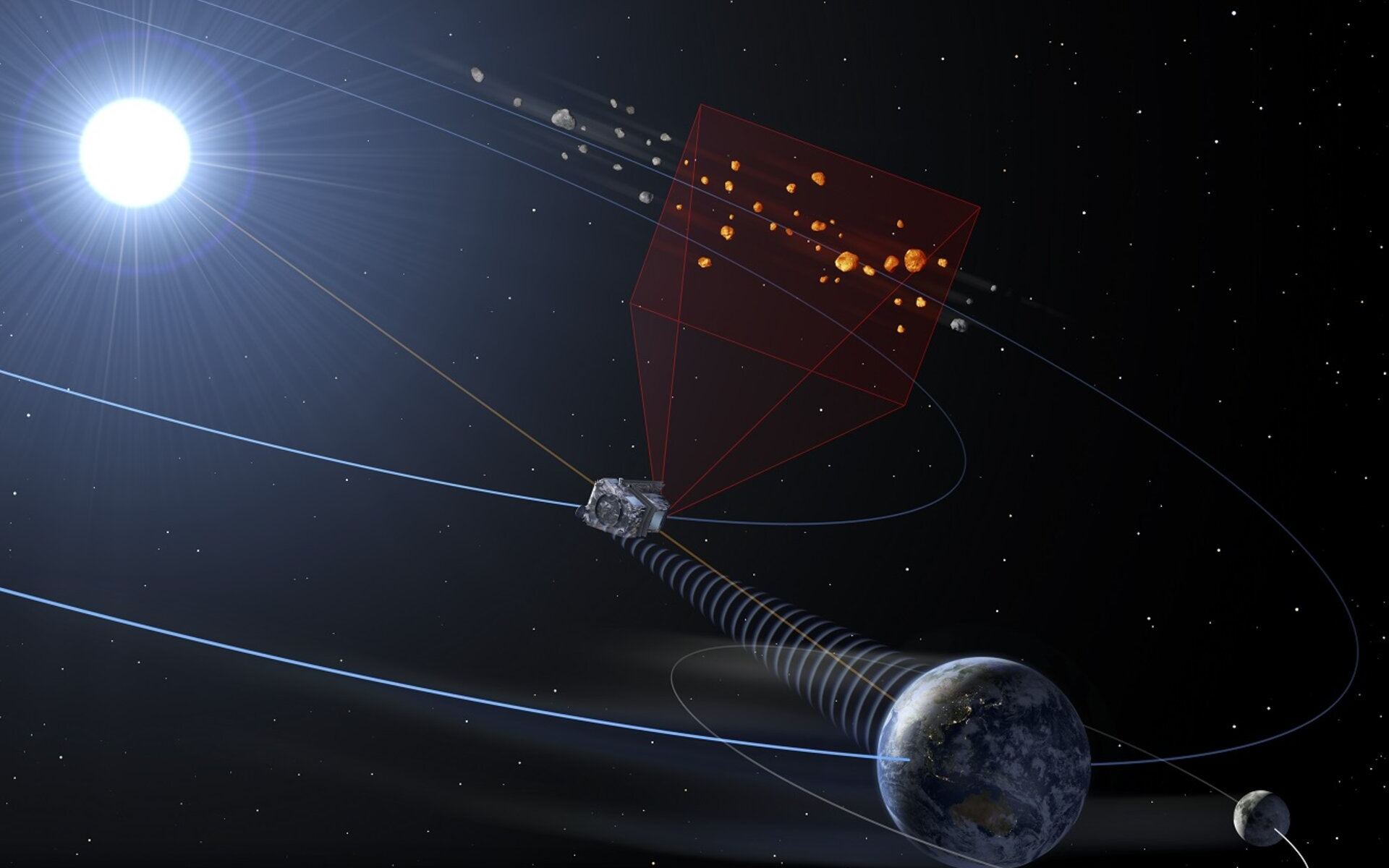

To bypass such problems, the European Space Agency plans to deploy NEOMIR, the Near-Earth Object Mission in the Infra-Red, a spacecraft carrying a compact telescope and placed at the L1 Lagrange point between Earth and the Sun (where the gravitational attraction of the two essentially “cancel each other out”, making it easier for a craft occupying the region to maintain its position). From here, Earth and the space around it would be in perpetual sunlight and the Sun would be “behind” the satellite, meaning that any objects in orbit around Earth or passing close to it will also be warmed by the Sun (and so visible in the infra-red), whilst sunlight would not be able to “blind” the satellite’s ability to see them.

The half-metre telescope carried by NEOMIR will be able to identify asteroids as small as 20m in size, and would generally be able to provide a minimum of 3 weeks notice of a potential impact with Earth’s atmosphere for objects of that size (although under very specific edge-cases the warning could be as little as 3 days), with significantly longer periods of warning for larger objects.

Currently, NEOMIR is in the design review phase, and if all goes well, it will be launched in 2030. In doing so, it will help plug a “gap” in plans to address the threat of NEO collisions with Earth: NASA’s NEO Surveyor mission, planned for launch in 2026, will also operate from the L1 position – but is only designed to spot and track objects in excess of 140m in diameter. Thus, NEOMIR and NEO Surveyor will between them provide more complete coverage.

At the same time as an update on NEOMIR’s development was made, China announced construction of its Earth-based Fuyan (“faceted eye”, but generally referred to as the “China Compound Eye”) radar system for detecting potential asteroid threats is entering a new phase of development.

The first phase of the system – comprising four purpose-built 16m diameter radar dishes – was completed in December 2022 within the Chongqing district of south-west China. Since then, the system has been pinging signals off of the Moon to verify the system and its key technologies.

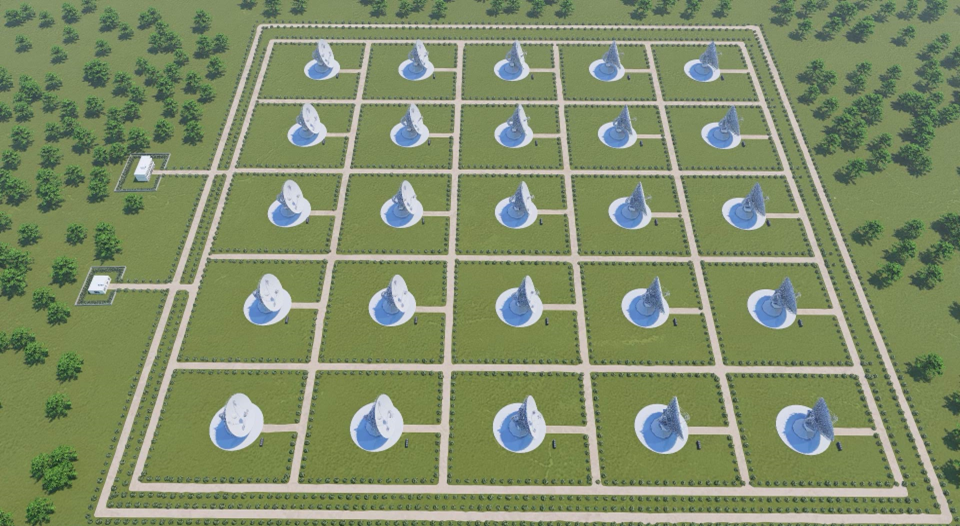

The new phase of work will see the construction of 25 radar dishes of 30m diameter, arranged in a grid. When they enter service in 2025, they will work in concert to try to detect asteroids from around 20-30m across at distances of up to 10 million km from Earth, determining their orbit, composition, rotational speed, and calculate possible deflections required to ensure any on a collision course with Earth do not actually strike the atmosphere.

As this second phase of Fuyan is commissioned, a third phase of the network will be constructed to extend detection range out to 150 million km beyond Earth. At the same time, China is planning to run its own asteroid deflection test similar to the NASA Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission, although the precise timeline for this mission is not clear.

In the meantime, 2023 CX1 was of the common type of near-Earth asteroids to regularly strike Earth’s atmosphere (at the rate of one impact every other week). It was discovered by Hungarian astronomer Krisztián Sárneczky, at Konkoly Observatory’s Piszkéstető Station within the Mátra Mountains, less than 7 hours before impact.

At the time of its discovery it was 233,000 km from Earth (some 60% of the average distance between Earth and the Moon), and travelling at a velocity 9 km per second. It took Sárneczky a further hour to confirm it would collide with Earth, marking 2023 CX1 as only the 7th asteroid determined to be on a collision with Earth prior to its actual impact.

The object – at that time still designated Star2667 – was tracked by multiple centres following Sárneczky’s initial alert, allowing for its potential entry into and passage through the upper atmosphere to be identified as being along the line of the English Channel, close to the coast of Normandy. It was successfully tracked until it entered Earth’s shadow at around 02:50 UTC on February 13th, just 9 minutes before it entered the upper atmosphere

As both the media and public were alerted to the asteroid’s approach, it’s demise was caught on camera from both sides of the English channel. It entered the atmosphere at 14.5 km/s at an inclination 40–50° relative to the vertical. As atmospheric drag increased, it started to burn up at an altitude of 89 km, becoming a visible meteor. At 29 km altitude it started to fragment, completely breaking apart at 28 km altitude as a bright flash as its fragments vaporised, finally vanishing from view at 20 km altitude, although meteorites fell to Earth in a strewn field spanning Dieppe to Doudeville on the French coast, sparking a hunt for fragments to enable characterisation of the object.

At the time of flash-fragmentation, the object released sufficient kinetic energy to generate a shock wave which was heard by people along the French coast closest to the path of the meteor and recorded by French seismographs.

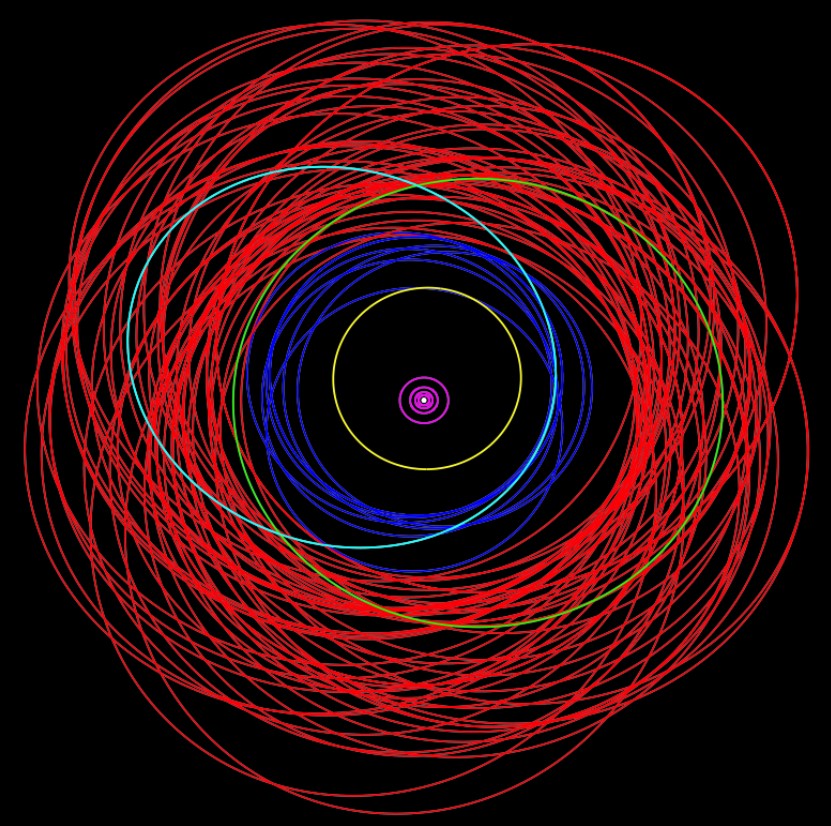

Following its impact, study of 2023 CX1 s orbital track revealed it to be an Apollo-type asteroid, crossing the orbits of Earth and Mars whilst orbiting the Sun at an average distance of 1.63 AU with a period 2.08 years. It last reached perihelion on 13th February 2021, ad would have done so again on March 15th, 2023 had it not swung into a collision path with Earth in the interim.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: asteroid impacts; ISS update”