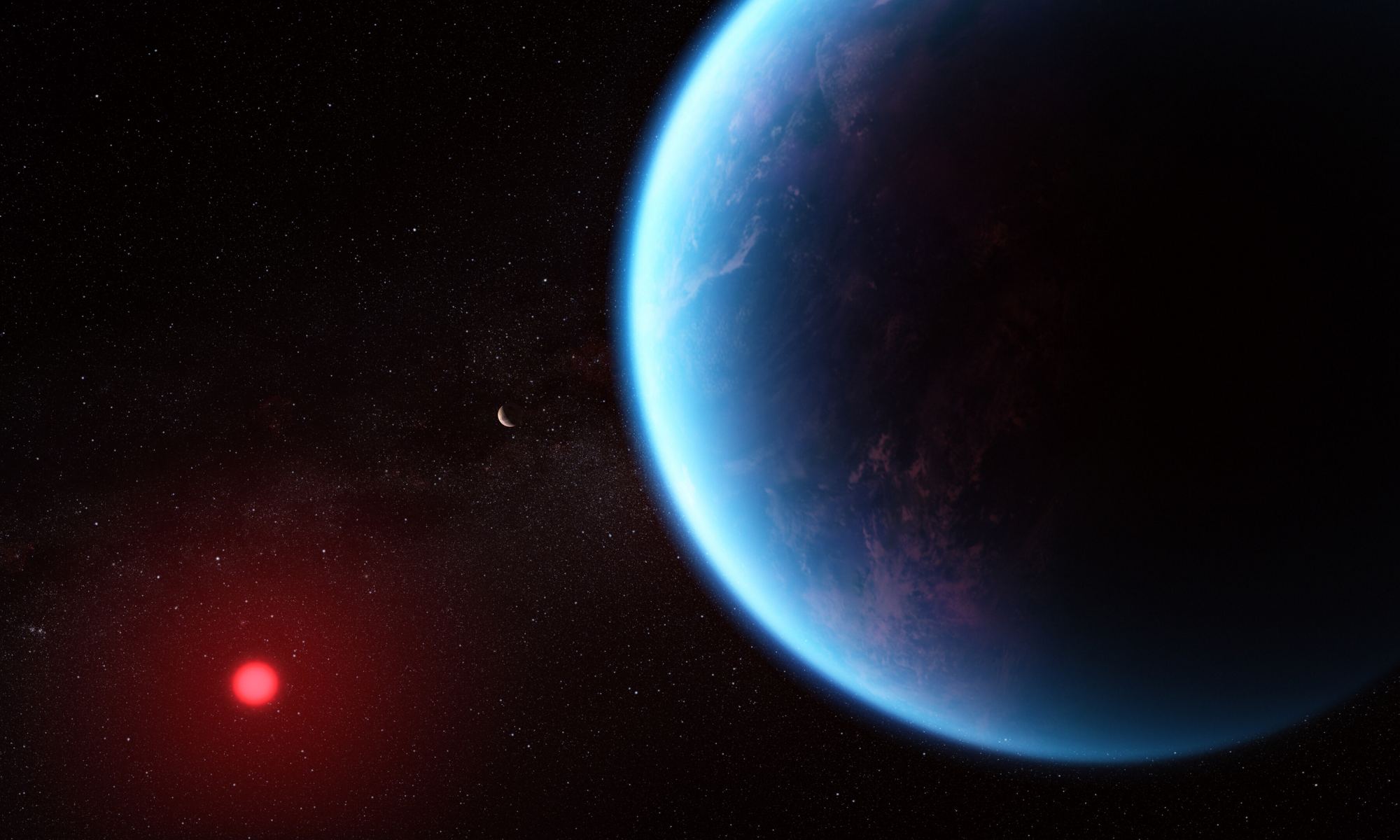

“Hycean world” may not be a term familiar to many. It refers to a type of hot, water-covered planet with a hydrogen atmosphere – “hycean” being a portmanteau from HYdrogen and oCEAN – sitting somewhere between Earth and Neptune in size, and which could be promising candidates for harbouring life, as they would be naturally warm and wet. However, there is a slight wrinkle in this theory: up until now, hycean planets have been purely hypothetical – although several contenders for the title have been identified.

One such contender is K2-18b, an exoplanet 124 light years away. It sits within the habitable zone of a relatively mild-mannered red dwarf star called K2-18 (and also EPIC 201912552), located within the constellation of Leo when viewed from Earth. First discovered by the Kepler mission in 2015, K2-18b is referred to as a “super Earth” because it is around 3 times the size and 9 times the mass of Earth, but smaller than Neptune (3.9 times the size and 17 times the mass of Earth).

From the start, it was known that K2-18b had an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen. Studies also showed that while it orbits in close proximity to its parent star, taking just 33 terrestrial days to complete an orbit – such is the star’s low energy output (just 2.3% that of the Sun), K2-18b receives a very similar amount of solar energy to the Earth: 1.22kW per square metre compared to our own average of 1.36kW per square metre. This means the planet likely has a global temperature range of between averages of −23°C at the poles and +27°C in the tropics, making it potentially ideal for hosting liquid water.

In 2019, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) found evidence that water vapour is present in K2-18b’s atmosphere, further edging it towards hycean status. However, the jury has remained out on the matter. The HST observations of 2019, for example, appeared to also find traces of ammonia and hydrocarbons – two elements which should not exist if there is also a large amount of liquid water present (as it would absorb them). Further, a 2021 study suggested that if K2-18b is tidally locked with its star (that is, always keeping the same side facing towards the star, which given their proximity to own another would seem likely), then any water on the sunward side of the planet would likely be in a supercritical state, making any form of liquid ocean impossible.

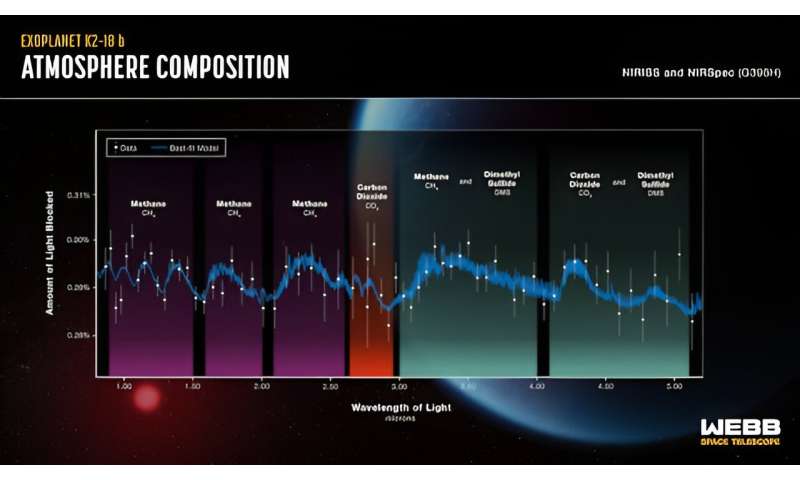

However, using the Near Infrared Spectrograph (NEARSpec) and Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) detectors on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) a team of astronomers from the UK and USA are attempting to build a comprehensive – if not yet complete – view of K2-18b’s atmospheric spectra. Their initial findings have been published in a new paper, and suggest that K2-18b might yet prove to be a hycean planet.

In particular, the paper confirms that HST did find water vapour in K2-18b’s atmosphere, it was wrong about the presence of ammonia and hydrocarbons; the team having found no trace of either – although they have found both methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, both of which also lean themselves to a potential for the planet having a liquid ocean.

More interestingly, the team also appear to have detected dimethyl sulphide, (CH3)2S – DMS for short. This is potentially a critical discovery, and so far as we know, DMS is the result of a wholly organic process: marine life and plankton giving vent to flatulence. If this is as true for K2-18b as for Earth, then the case for that planet having a liquid water ocean becomes pretty clear.

However, a note of caution needs to be struck here. As the researchers themselves make clear, the signal for DMS within K2-18b’s atmosphere is only 2 sigma. While this equates to a 98% confidence level in the instruments on JWST having correctly identified it, the results nevertheless fall far short of the 5 sigma (over 99.9% confidence) required by science to indicate the instruments have correctly identified the presence of a particular element within the atmosphere of another world. As such, further examinations of K2-18b’s atmosphere need to be made to see if that 5 sigma level can be achieved – or if the DMS traces fade away to nothing.

And even if the DMS readings prove to be correct, it again doesn’t automatically mean the planet is home to life. Whilst the sole cause for DMS here on Earth is that of marine life farts, the same may not be true for other places in the galaxy; it might yet be show the some strange geological or chemical cause might be responsible for its presence. Nevertheless, the data thus far obtained by JWST do suggest that K2-18b could be a warm, naturally wet planet – and potentially points the way to other such worlds existing within the galaxy.

Are Pollutants a way to find Industrial Civilisations?

Using the transit method of analysing the atmosphere of a planet, as with the case of K2-18b above, is one of the best ways we have at our disposal to determine its potential to support life. However, it might also be the means of detecting technological life itself – as pointed out by an international team led by Canadian–American astronomer and planetary scientist Sara Seager.

As we’re only too aware, humanity has developed a nasty habit of buggering up Earth’s atmosphere with pollutants. Some of these have very clear spectral signatures and cannot be produced in quantity by natural means. As such, looking for them elsewhere might be indicative of the worlds where they are found being home to industrial civilisations.

Take sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3), as Seager and colleagues suggest. These are two inorganic greenhouse gases (NF3 for example, is 17,000 times more effective at warming the atmosphere than CO2). Both are artificially created, and are used by a number of modern industries. What’s more, they have very distinctive spectral signatures and very long half-lives; as such they have the potential to make ideal “technosignatures” if they were to be detected in the atmosphere of an exoplanet.

Of course, this also requires that any extra-solar civilisation follows something of a similar development path as we are on, but it is an intriguing idea. In fact, and as Seager and her team note, whilst fluorine might be the 13th most abundant element on Earth, very little of it occurs naturally in any form; most of it is produced (and used) in industrial processes. So again, should the analysis of an exoplanet’s atmosphere reveal multiple fluorine elements, there’s a fair chance (again using Earth as a model) they might point to a technological civilisation being present.

Resuming the Hunt for “Planet Nine” – Or Its Economy Sized Version

I’ve covered the conundrum of Planet Nine – the Neptune-sized planet some believed to be orbiting the Sun at an average distance of around 460 AU and responsible for chucking a number of Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) into highly unusual orbits of their own well outside of the plane of the ecliptic – numerous times (see here, here, and here, for more).

Most vigorously proposed and pursued by Mike Brown, a leading planetary astronomer at the California Institute of Technology, it was a contentious idea – most notably because of the small data pool from which Brown and his colleagues drew on to establish the whole idea of “Planet Nine”. It was also one that quickly came into doubt as repeated attempts to locate the mystical world failed to do so and evidence against such a large planet existing continued to mount.

When I last wrote about this situation, back in June 2020, it was to cover the work of Professor ssistant professor of astronomy, University of Regina, Canada. Due in part to her involvement in the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS), coupled with models such as the Nice Model (as in the town in France, not “nice”) of planetary migration, she was able to demonstrate the vast majority of eccentric KBOs could be accounted for through purely natural gravitational interaction. Most, that is, but not all; as she noted in her findings, small groups of KBOs remain a outliers, defying explanation for their eccentricities.

Some of the latter lie within a sub-category of KBOs referred to as trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). These are objects with obits close enough to that of Neptune so as to be directly influenced by its gravity, which forces them into very defined modes of behaviour. However, a small percentage of TNOs (approx. 13% of the total) refuse to show any sign of being under Neptune’s influence, almost as if there is something else acting on them gravitationally and limiting Neptune’s ability to call them to heel; something perhaps like a yet-to-be discovered “Planet Nine”; albeit one on a much smaller scale than previously imagined – its economy-sized version, if you will.

The idea has grown out of unrelated research concerning the early development of the solar system. In running hundreds of simulations on how the solar system may have formed, and the planets – particularly the gas giants – migrated away from the Sun, researchers noted their models repeatedly formed multiple Earth-sized planets in the outer solar system. The exact number varied with each simulation, but they all shared the common fate of either being completely ejected from the solar system thanks to the outward migration of the gas giants, or – in the case of a small handful – being pushed into very distant orbits around the Sun where they have yet to be found.

Most interestingly, the researchers noted that if just one of these small planets – one with a mass around twice that of Earth – were to be pushed into a high inclination orbit – say 45º – and at an average distance of just 200 AU from the Sun, then it could have the potential to exert influence over the recalcitrant TNOs in a manner pretty close to their actually behaviour, and similarly affect other outlier KBOs.

Those behind the study are not proposing that there is a “mini-me” Planet Nine tap dancing its away around the Sun; merely that their work has thrown up some potentially interesting results. Nevertheless, in some quarters it has somewhat reinvigorated the whole idea of a distant planet (or even planets) still awaiting discovery as they make their way slowly around the Sun, and so the hunt may yet resume.