We are currently approaching the mid-point in Cycle 25 of the Sun’s 11-year cyclical solar magnetic activity. These are the periods in which observable changes in the solar radiation levels, sunspot activity, solar flare and the ejection of material from the surface of the Sun, etc., go from a fairly quiescent phase (“solar minimum”) to a very active phase (“solar maximum”) before declining back to a quiescent period once more to repeat the cycle again. The “11-year” element is the average length of such cycles, as they can be both a little shorter or a little longer, depending on the Sun’s mood. They’ve likely been occurring over much of the Sun’s life, although we only really started formally observing and recording them from 1755 onwards, which is why this cycle is Cycle 25.

This cycle started in December 2019, and is expected to reach its mid-point in July 2025, before declining away in terms of activity until the next cycle commences in around 2030. Predictions as to how active it might be varied widely during the first year or so, (2019-2021), with some anticipating a fair quite cycle similar to Cycle 24; others predicted it would be more active – and they’ve been largely shown to be correct. And in this past week, the Sun has been demonstrating that while it might be middle-aged, it can still get really active, giving rise to spectacular auroras visible from around the globe.

The cause of this activity carries the innocent name of AR3664 (“Active Region 3664”), a peppering of sunspots – dark patches on the solar surface where the magnetic field is abnormally strong (roughly 2,500 times stronger than Earth’s) – on the Sun, and one of several such groups active at this time. However, AR 3664 is no ordinary collection of sunspots. In a 3-day period between May 6th and May 9th, it underwent massive expansion, growing to over 15 Earth diameters in length (200,000 km), and at the time of writing is around 17 Earth diameters across.

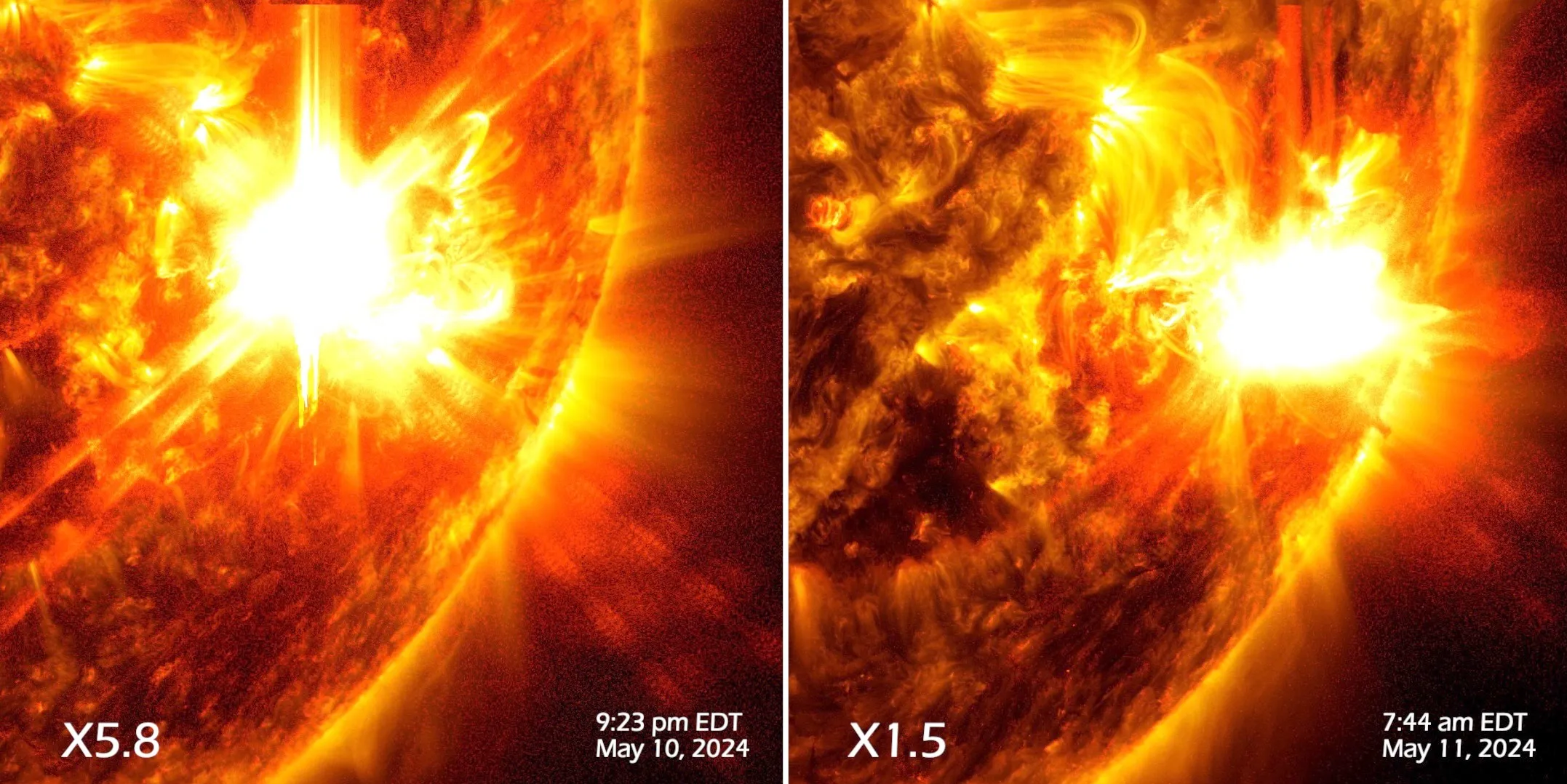

This rapid expansion gave rise to a series of huge dynamic solar flares on the 10th/11th May, with the first a massive X5.8 class flare – one of the most powerful types of solar flare the Sun can produce. Accompanying the flares have been interplanetary coronal mass ejections, which since Friday have been colliding with Earth’s magnetosphere, causing geomagnetic storms and auroras, giving people spectacular night skies.

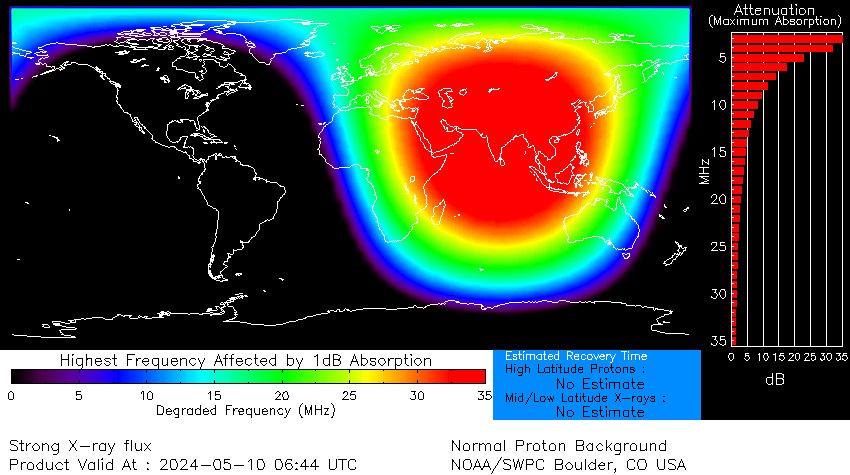

The first of these geomagnetic storms was classified G5 – the highest rating, and the first extreme storm of this type to strike our magnetosphere since October 2023, when damaged was caused to power infrastructure and services in several countries, including Sweden and South Africa. This event caused high-frequency radio blackouts throughout Asia, Eastern Europe and Eastern Africa, and disrupted GPS and other commercial satellite-directed services, although overall, the impact was fairly well managed.

Further storms were experienced through Friday, Saturday and Sunday (10-12th May), varying between G3 and G4 as a result of further CMEs from AR 3664, together with further solar flares in the X4 range. Storms and auroras are expected to continue through until Monday, May 13th, after which AR 3664 will slip around the limb of the Sun relative to Earth.

Thus far, cycle 25 has seen daily sunspot activity around 70% higher during the peak period when compared to Cycle 24, although most of the resultant flares and CMEs have tended to be well below the extreme levels of the last few days. Whether AR 664 marks the peak of events for this cycle, or whether we’ll have more is obviously a matter for the future – but if you’ve not had the opportunity to witness the aurora, the nights of the 12th/13th May might be a good opportunity to do so!

AR 3664 is, coincidentally, believed to be around the same size as the sunspot cluster thought to have been responsible for the 1859 Carrington Event, the most intense geomagnetic storm in recorded history (Cycle 10), resulting in global displays of aurora and geomagnetic storms, the latter of which massively disrupted telegraphic communications across Europe and North America (and lead to reports of telegraph operators getting electric shocks from their morse keys and still being able to send and receive messages even with their equipment disconnected from the local power supply!).

Take a Plunge into a Black Hole – Or Fly Around it

Black holes are mysterious (and oft misunderstood) objects. We all know the basics – they are regions on spacetime where gravity is so great that not even light can escape past a certain point (the event horizon) – but what would it be like to fall into one or pass into orbit around one?

In the case of the former, we may think we know the answer (stretching / spaghettification, death + a different perspective of time compare to those observing us from a safe distance), but this is not actually the case for all black holes; it comes down to the type you fall into.

In the case of stellar black holes, formed when massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle, it’s unlikely you’ll ever actually reach the event horizon, much less fall into it; the tidal forces well beyond the event horizon will rip you apart well in advance. But in the case of supermassive black holes (SMBHs), such as the one lying at the centre of our own galaxy (and called Sagittarius A*) things are a little different.

These black holes are so mind-bogglingly big that the gravity curve is somewhat “smoother” than that of a stellar black hole, with the tidal forces more predictable, possibly allowing the event horizon to be reached and crossed (giving rise to spaghettification). Even so, trying to define what goes on in and around them is still somewhat theoretical and based on abstracted concepts drawn from indirect observation and complex maths.

So, to try to get a better handle on what the maths and theories predict should happen around something like a SMBH – such as falling into the event horizon or being able to orbit and escape such a monster, NASA astrophysicist Jeremy Schnittman – who is one of the foremost US authorities on black holes – harnessed the power of NASA’s Discover supercomputer (with over 127,000 CPU cores capable of 8,100 trillion floating point operations per second), and used available data on Sagittarius A* to generate two visual models which make for a fascinating study.

In the first, the camera takes us on a ride from a distance of some 640 million km from the SMBH (a point at which its gravity is already warping our view of the galaxy), through the accretion disk and into a double orbit around the black hole before gravity is allowed to pull the camera in and across the event horizon. It provides a unique insight into how the galaxy around us would appear, how time and space are bent (and eventually broken), whilst also offering an enticing view of another black hole phenomenon: photon rings – particles of light which are travelling fast enough to fall into orbit around the black hole and loop around it more than once before escaping again.

I’ll say no more here, the video explains itself.

In the second video (below), the camera passes around the black hole for two orbits before breaking away, just like the light particles responsible for the photon rings. As well as the visualisation of the warping effect gravity that a black hole has on light, both videos also demonstrate the time dilation effect created by the SMBH’s gravity.

In the “orbital” video, eat loop around the black hole takes – from the camera’s perspective – 30 minutes to complete. However, from the perspective of someone watching from the video’s starting point, 640 million kilometres away, each orbit appears to take 3 hours and 18 minutes. Meanwhile, in the “fall” video, from the camera’s perspective, the drop from orbit to event horizon lasts 10 minutes. However, from anywhere beyond the black hole, it never ends; the object appears to “freeze” in place the moment it touched the event horizon (even though it is ripped apart nanoseconds after crossing the event horizon).

And these dilation effects assume the black hole is static; if it happened to be rotating – then in the case of camera orbiting the black hole and then braking free, mere hours may seem to have passed – but to the observers so far away, years will have seemed to pass.

Updates

Starliner CFT-1 Delayed

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner continues on the rocky road to flight status. As I reported in my last Space Sunday, CST-100 Calypso was due to head off to the International Space Station (ISS) on Monday, May 6th, carrying NASA astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams on a Crewed Flight Test (CFT) designed to pave the way for the spacecraft to be certified for operations carrying up to 4 people at a time to / from the ISS.

Only it didn’t; the launch was scrubbed some 2 hours ahead of lift-off due to issues in the flight hardware – although this time, thankfully, not with the vehicle itself. The fault lay within an oxygen relief valve in the Atlas V’s Centaur upper stage, of the Atlas V launch vehicle. The valve was cycling open and closed repeatedly and so rapidly that crew on the pad could hear it – describing is as a “buzzing” sound.

Initially, it had been hoped that the issue could be rectified without moving the vehicle back from the pad at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, and that a launch date of May 10th could be met. However, by May 8th, attempts to reset the valve via software and control intervention had failed, and ULA – the company responsible for the Atlas V and its upper stage (ironically, the Centaur is produced by Boeing, one of the two partners in ULA) – decided the stack of rocket and Starliner would have to be rolled back to the Vertical Integration Facility (VIF) close to the pad, so the entire valve mechanism can be replaced.

As a result, and at the time of writing, the launch is now scheduled to take place on Friday, May 17th, with a lift-off time targeting 23:16 UTC.

Hubble Back, TESS Down, Up, Down, Up

On April 28th, I reported that the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) had entered a “safe” mode following issues with one of its three remaining pointing gyroscopes. As noted in that piece, the gyroscopes are a vital part of HST’s pointing and steadying system, and while it generally requires three such units for Hubble to operate efficiently, it can get by at a reduced science capacity with only two – or even one, if absolutely necessary – functional gyro.

These gyros do naturally wear out – six brand new units were installed in 2009 (pairs of primary and back-up), but since then, three have permanently failed, and one of the remaining three has been having issues on-and-off since November 2023. Fortunately, in the case of that issue, and now with the April 23rd problem, engineers on Earth were able to coax the gyro back into working as expected. Thus, in the case of the latter, Hubble was back on science gathering duties with all instruments were operational on April 30th.

Quite coincidentally, another of NASA’s orbiting observatories – the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) – also entered a “safe” mode on April 23rd, 2024 – the second time in April its did so. On April 8th, 2024 TESS suddenly safed itself without any warning, and remained off-line for science operations through until April 17th, when the mission team managed to restore full service. However, what triggered the safe mode in the first place has yet to be identified; so when TESS slipped back into a safe mode on April 23rd, engineers looked to see if there was a connection. There, was – but not in the way they’d hoped.

In order to restore TESS to an operational status on April 17th, the mission team had to perform an “unloading” operation on the the flywheels used to orient and stabilise the observatory. This is a routine activity, but it requires the use of the propulsion system to correct for any excess momentum held by the flywheels that might get transferred directly to the spacecraft and cause it to lose alignment. This in turn requires the propulsion system to be properly pressurised. Unfortunately, this was not completed correctly, and the thrusters were left under-pressurised. As a result, a small amount of momentum was transferred to TESS’s orientation, gradually swinging it out of expected alignment until it reached a point where the main computer realised something was wrong, triggered the safe mode and ‘phoned home for help.

Given this, the fix was relatively simple: correctly pressurisation the propulsion system and gently nudge it to stabilise TESS once more so it is aligned in accordance with its science operations.