Back in 2021 I wrote about Space Perspective, a (then) relatively new entry to the field of sub-orbital space tourism and – if I’m honest – the one I’d really like to try (see: Space Sunday: balloons to space, Mars movies and alien water clouds).

At a time when Blue Origin are lobbing place to the edge of space in ballistic capsules and Virgin Galactic has been (although currently on hiatus) chucking them not-quite-so-high on rocket planes, Space Perspective came up with an altogether more sedate – and longer duration approach to giving people a taste of space: send them up in a balloon.

When I first wrote about the endeavour, Space Perspective planned to offer flights for up to 8 passengers and 2 crew starting on land, using a purpose-built balloon with a luxury capsule slung beneath it to carry them up to around 30-32 km altitude (not high enough to qualify for astronaut wings but more than enough to witness the curvature of the Earth and see it passing below as the 6-hour flight heads out to sea) before descending to a splashdown and a return to dry land aboard a luxury boat.

Since then things have changed somewhat. Whilst the overall goal remains the same – and the prototype capsule for the flights, called Neptune, has made a number of demonstration flights, once the system is approved and operational, the entire flight will commence and end at sea, launched and recovered via a purpose-equipped vessel.

The MS (Marine Spaceport) Voyager, as the vessel is known, is a former 3,100 tonne displacement oil platform support vessel (OSV) measuring 90 metres in length, 61 metres of which is a flat working deck which has been specifically outfitted for the launch and recovery of the company’s balloons and capsules. The term “Marine Spaceport” replaces the more usual usage of MS (“Motor Vessel”) to indicate the ship is intended to be a fully ocean-going launch and recovery vessel. Initially it will operate of the United States Space Coast, Florida, but Space Perspective is already eyeing the potential to offer flights out of the Caribbean and other wealthy tourist retreats, thus bringing the thrill of edge-of-space flight to the potential travellers, rather than making them travel to the launch pad.

The name Voyager was chosen in direct reference to NASA’s Voyager mission programme, and specifically Voyager 1. Billed as the “first” in its class and operated by specialist marine and aerospace recovery company Guice Offshore on behalf of Space Perspective, both companies have hinted further vessels (Voyager 2?) might be made available in the future.

The capability to launch and retrieve the Neptune capsule at sea creates worldwide scalability along with an unprecedented closure of the routine operations safety case. We are proud to bring a new spaceflight capability to Port Canaveral and the Space Coast.

– Taber MacCallum, founder and co-CEO of Space Perspective

Whilst no dates have been given, Space Perspective has indicated the next phase of work is to test launch and recovery operations using the Neptune capsule. After these, the company expects to move towards obtaining a commercial license for passenger operations and then to offering flights.

Tickets for the latter have already been offered by the company at US $125,000 per head – far less than either Virgin Galactic or Blue Origin, although both of the latter do offer periods in microgravity, which Space Perspectives cannot provide. The company has not revealed how many tickets it has sold in advance of commencing operations.

The Great Lake of Mars

Mars is a small world when compared to Earth, but it likes to do things big. There’s Olympus Mons, the massive shield volcano , rising almost 22km above the Mars datum (compared to Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea rising some 9-10km above the sea floor on Earth), and covering an area as much as 300,000 sq km in size (compared to the10,430 sq km of the Island of Hawaii). Or there’s the 4,000+ km length of the Vallis Marineris, in places 7 km deep and more than capable of regarding the 447 km long and 1.6 km deep Grand Canyon as a mere tributary.

Both of these feature are very well known to people even with just a passing interest in Mars. But there is another remarkable – if less obvious – feature on Mars which has been the subject of extended study by Europe’s 20-year Mars orbiting veteran, Mars Express.

Located in the planet’s southern hemisphere, and badly scarred and weathered by impact craters and the passage of time, are the remnants of a vast lake – or perhaps sea might be a better description – that at some point in the ancient Martian past may have been up to 1 km deep, a depth similar to the extent of the southern end of the Caspian Sea, Earth’s largest inland sea. However, where the latter covers an area of some 386,400 sq km, Eridania Lake on Mars once covered an area of some 1.1 million square km – big enough to hold three times the volume of water by volume than the Caspian Sea. And if you’re wondering about how this compares to the Great Lakes in North America, the largest bodies of freshwater on Earth, they “merely” cover an area of some 244,100 sq km with a maximum depth of around 406 metres.

However, like the Great Lakes, Lake Eridana consists of several interconnected basins, all of which likely held water as a common lake between 4.1 and 3 billion years ago. These basins are still visible on the surface of Mars today and, and are now officially called the Ariadnes Colles (“hills”), Coralis Chaos, Atlantis Chaos, Simois Colles, and Gorgonum Chaos.

What is particularly interesting about this region is not the fact it was once a vast lake, but that it is exceptionally mineral and clay rich (the clay deposits being up to 2 km thick), with many of the detected minerals showing clear signs of volcanic origins. This means that the lake bed could once have been home to hydrothermal vents; thus Eridana potentially offered everything life needed to bring itself into being back in the Martian pre-history: the right chemicals and minerals, a source of water, and a source of heat / energy.

The clearest evidence for the region being subject to the effects of volcanism is not so much in the presences of ancient volcanic peaks, but from the presence of significant fault lines collectively called the Sirenum Fossae. Over 2,700 km in length, these fault lines sit either side of a trough of land which dropped below the mean surface level to form a graben as the land either side of the faults was pulled apart. It’s believed this occurred when the crust of the planet was under enormous strain as the massive Tharsis bulge with its three huge volcanoes was forcing itself upwards half a world away, allowing liquid magma to channel its way up to the heat the lake bed, giving rise in turn to the hydrothermal venting.

The hills of Ariadnes and Simois Colles are thought to have been mounds of material deposited within the lake during the early-to-mid Noachain period, when Mars is thought to have been most abundant in liquid water. As the water began to recede in the latter part of the Noachian period (round 3.8 to 3.7 billion years ago), material was exposed to the Martian weather and subject to sculpting into mounds.

Then, in the Hesperian period (3.7 to around 3.0 billion years ago), the region of the lake were subject to perhaps multiple periods of flood and clearing (along with other parts of the planet) as volcanism took more widespread hold on the planet and the likes of Olympus Mons formed, whilst the volcanoes of Tharsis and Elysium added their voices to the choir of eruptions and disruptions. This ebb and flow of water further shaped the vast fields of mounds before they were again exposed to the (much calmer by this time) Martian winds, which have been shaping them ever since.

Such is the wealth of potential science there that the region was proposed as a possible landing zone for NASA’s Mars 2020 rover Perseverance.

Despite the fact that Eridania floor has been mapped as a volcanic ridged plain, several sedimentary mineralogies have been recognised there corroborating i) a low-energy and long-lasting (Late Noachian to Early Hesperian) depositional environment characterised by the presence of ponding water, and ii) a warm Martian paleoclimate with a stable highland water table more than ∼3.5 billion years ago.

For all the above reasons, the Eridania surface provides great potential to search for prebiotic chemistry and past exobiological life: thus we are proposing this region as the Mars 2020 landing site.

– Pajola et al, 2016: Eridania Basin: An ancient paleolake floor as the next landing site for the Mars 2020 rover

Ultimately, and for a variety of reasons, the region was passed over in favour of other locations and, eventually, Jezero Crater was selected as the landing zone for Perseverance. However, the continuing study of Eridania is again awakening calls for a robotic mission there – if a suitable landing zone can be located. Not only does the region offer a fascinating mineralogical history of Mars and the potential for studies into both prebiotic chemistry and potential past biological activity, the richness of the minerals and compounds identified within the clays of the region could potentially preserve the characteristics of the ancient atmosphere and climate. Thus studying them even in the absence of any evidence for organic activities within the clays of the region could do much to further unlock the ancient history of Mars.

Starliner to Remain, Crew-9 Delayed and Embarrassment Rises

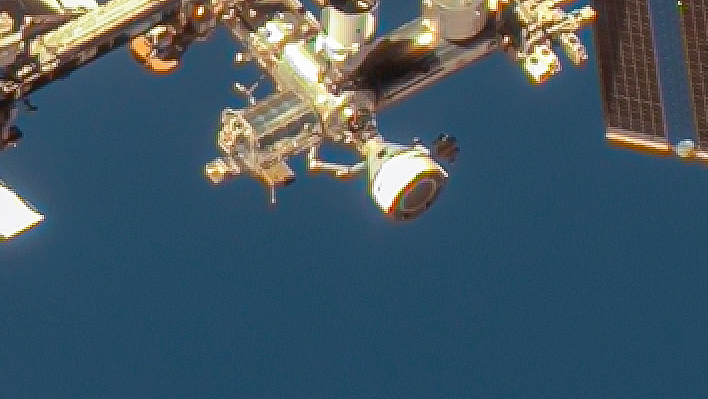

So the Starliner saga continues. As noted last time out, the decision on when (and how) to return Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner to Earth was awaiting further review of data on the end-of-July “hot fire” tests of the vehicle’s thrusters systems both on Earth and on the International Space Station (ISS).

At the time of that update, things looked good from both a Boeing and a NASA perspective, but NASA delayed detailed commentary on the results for a week to allow further reviews of the data. These have been carried out, and appear to show there are still issues which may or may not be related to the overheating problem. As the precise cause of the additional issues cannot be determined, NASA announced on August 7th that the Starliner vehicle, comprising the reusable capsule Calypso and its non-reusable service module, will remain at the ISS until mid-August at least.

This announcement came a day after NASA indicated that the Crew 9 mission due to launch to the ISS on August 18th would be delayed until no earlier than September 24th (something I indicated might be the case in my last update). However, during the August 7thbriefing, NASA did make the admission they are now looking at alternate ways to potentially bring the Starliner’s crew of Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams home, if necessary.

The most likely scenario for this would launching the Crew 9 mission with only two people on board – most likely Commander Zena Cardman and Pilot Nick Hague, leaving 2 seats free for Williams and Wilmore (although their space suits are different to those used by SpaceX, so this would have to be worked through). Wilmore and Williams would then remain aboard the ISS as a part of the Crew 9 rotation (Expedition 72), returning to Earth with Cardman and Hague in March 2025. As veterans of previous ISS crews (Wilmore as a part of the Expedition 41 rotation in 2014 and Williams as part of both the 2006/7 Expedition 14 and Expedition 32 rotations in 2012), they are more than qualified for such an extended stay.

If the case, this would not be the first time a crew has faced an extended stay on the ISS – as many commentators seem to have forgotten.

In September 2022 cosmonauts Sergey Prokopyev, Dmitry Petelin and NASA astronaut Frank Rubio arrived aboard the ISS for a 6-month rotation. Three months into their stay, their space vehicle, Soyuz MS-22 suffered a major coolant leak, rendering it unfit for crewed flight. Instead, in February 2023, Russia launched Soyuz MS-23 to the space station without its crew of three. Rubio, Petelin and Prokopyev then remained on the ISS through the end of September 2023, carrying the work planned for the original MS-23 crew.

However, this would then require the Starliner to make an automated return to Earth. In theory, Starliner is fully capable of doing this (unlike SpaceX Dragon), having a fully automated flight control software suite. This was demonstrated in May 2022 with the unscrewed Orbital flight Test 2 in May 2022. The problem here being that Calypso was launched without some (or all) of the necessary software (notably, the software required for the vehicle to automated undock and move away from the ISS).

While this is partially understandable – this flight was, after all, intended to test the vehicle under human control – it is nevertheless highly embarrassing that neither Boeing nor NASA sought to ensure the automated flight software was available on Calypso just in case it was needed. Instead, the software would have to be uploaded, configured and tested – a process that could take up to 4 weeks to complete.

This lead to something of a public tiff between company and agency, Boeing aggressively stating the craft is fully capable of a crewed return to Earth. NASA, however, isn’t (rightly) open to taking chances with its personnel – so for now the saga will continue.