Update: October 6th: Two hours after this article was published, NASA announced launch operations for the Europa Clipper mission are standing down, and the launch postponed due to Hurricane Milton. A new target launch data will be announced once the hurricane has cleared the Florida Space Coast and any damage to facilities at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s SLC-41 launch pad assessed.

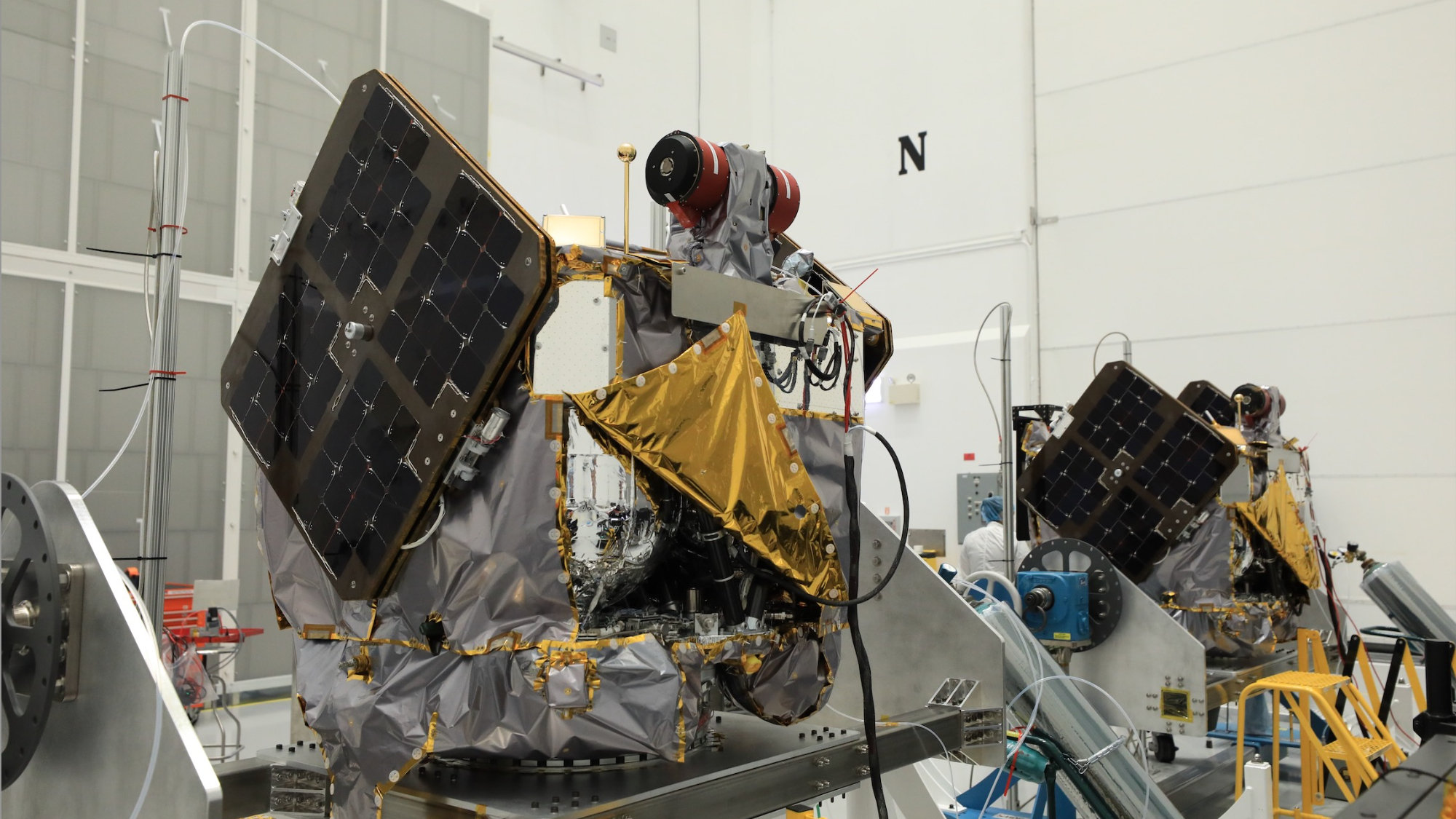

If all goes according to plan, October 10th should see the launch of the second of NASA’s Large Strategic Science Missions of the 21st century (formerly called Flagship missions, and the first having been the James Webb Space Telescope): Europa Clipper.

The launch will see a SpaceX Falcon Heavy carry a NASA space probe bearing the same name as the mission on the first leg of a 5.5 year journey to Jupiter to study the Galilean moon of Europa. In order to achieve this goal, the spacecraft will be directed towards Mars, which it will reach in February 2025. Using the Martian gravity as a brake, the spacecraft will fall back toward the Sun and encounter Earth again in December 2026, using our planet’s gravity to fling it out on a trajectory to reach Jupiter in April 2030.

On arrival at Jupiter, the vehicle will enter an initial orbit that will then be refined, allowing it to make some 44 fly-bys of Europa varying between just 25 km above the surface and 2,700 km. The reason fly-bys will be made rather than the craft entering orbit around Europa directly is large due to radiation. Europa lies well within Jupiter’s extreme and intense radiation belts, an environment so harsh that it would fry the spacecraft’s electronics and electrical component – notably the huge solar arrays which generate its power – in just a few months after its arrival.

In addition, the spacecraft is carrying a significant science payload which can gather data much faster than the communications system can transmit it to Earth; were it to be placed in orbit around Europa, the opportunities to transmit the data its has would be subject to a a range of limitations (such a when Jupiter is between the probe and Earth), risking data loss due to existing data being overwritten before it could be transmitted.

By taking up an orbit around Jupiter and simply swinging by Europa, the space craft may lose opportunities for gathering data, but it increases the time available for the successful transmission of the data it does collect safely. Rather than having mere minutes or hours in which to send information, the probe will have between 7 and 10 days at a time. Further, by orbiting Jupiter rather than Europa, the spacecraft “dips” in and out of the harshest radiation, rather than being subjected to it all the time, thus preserving its electronics for much longer, and allowing it a primary science mission of an initial 3.5 years.

To assist it whilst orbiting Jupiter, Europa Clipper will use 24 thrusters connected to a hypergolic propulsion system with 2.7 tonnes of propellants. Up to 60% of this mass will be used during the initial orbital insertion phase around Jupiter in April 2030, with the rest used in stabilising the spacecraft and orienting it during Europa fly-bys and communication periods with Earth to maximise data gathering and transmission.

The suite of nine instruments on the vehicle will be used to study Europa’s interior and ocean, geology, chemistry, and habitability. The science payload accounts for some 82 kg of the vehicle’s mass and includes a pair of imaging cameras operating in visible light wavelengths, and both a thermal imaging system and a near-infrared imaging system which will search for the likes of dynamic activity on the icy-covered surface of Europa (e.g. vents venting water and sub-surface material into space) and the distribution of organic material across the moon’s surface.

The vehicle also carries an instrument called REASON – the Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (NASA still reign supreme in the acronym stakes!) – an ice-penetrating radar designed to characterise the 10-30 km (estimated) thick ice crust of the moon, seeking information on its composition and any indications of water pockets within it, any exosphere existing just above it as a result of venting, and – hopefully – reveal something of the nature of the upper limits of the liquid water ocean sitting under the lowest extent of the ice, between it and Europa’s rocky mantle.

Whilst it has launched some 18 months after ESA’s JuICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer – see: Space Sunday: a bit of JUICE, a flight test & celebrating 50) mission, Europa Clipper will arrive in Jupiter orbit more than a year ahead of it by virtue of being launched atop a more powerful launch vehicle. In doing so, it will take over from the Juno mission as NASA’s lone research spacecraft orbiting Jupiter (the Juno mission is expected to come to an end in September 2025, the vehicle having exhausted the vast majority of its propellants, leaving only sufficient for it to make a controlled entry into Jupiter’s upper atmosphere and burn-up).

During its fly-bys of Jupiter, the Juno spacecraft has also been able to study the Galilean moons as well, and while the mission’s overall science goals have been very different to those of the Europa Clipper and JuICE missions, they are nevertheless somewhat foundational, helping both NASA and ESA better understand the environment in preparation for JuICE and Europa Clipper. Once both craft are in orbit around Jupiter, the respective science teams will work closely together, JuICE being tasked with studying Europa as well as the other two potentially water-bearing moons of Jupiter, Ganymede and Callisto.

In all, should the October 10th launch opportunity be missed (e.g. due to weather), the Europa Clipper launch window will remain open for a further 20 days.

Vulcan Triumphs despite SRB Anomaly

United Launch Alliance (ULA) completed the second launch of its new Vulcan Centaur rocket on Friday, October 4th, and despite a significant issue with one of its Northrop Grumman GEM-63XL solid rocket boosters (SRBs), the vehicle went on to ace the flight.

Vulcan Centaur is a ULA’s replacement for both the veritable Atlas and Delta families of launchers, and like them it is currently fully expendable. I covered its successful maiden flight for the vehicle, sending the ill-fated private lunar lander Peregrine One by in January 2024 (see: Space Sunday: lunar losses and delays; strings and rings). Following that flight, ULA had hoped to launch Vulcan again in April 2024, carrying aloft Tenacity the first of the Dream Chaser cargo space planes being developed by Sierra Space; however, delays with Tenacity’s final preparations now means this launch has been pushed back until at least March 2025. Instead, ULA decided to go ahead with flight designed to certify it for DoD launches, using a payload mass simulator in place of an actual payload.

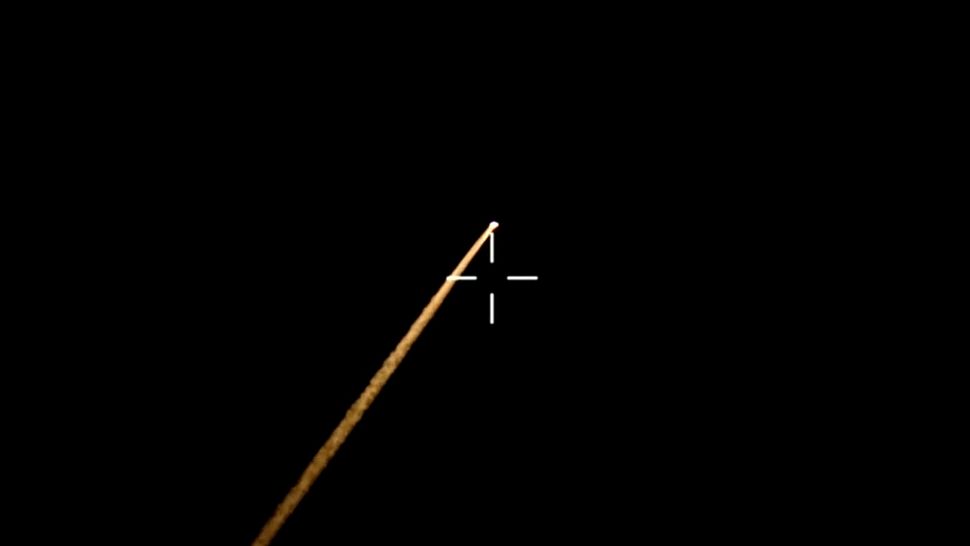

Launch came at 11:25 UTC on October 4th, the vehicle lifting-off from Launch Complex 41 (SLC-41) at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in after around a 30-minute delay. After clearing the tower, it became obvious that the right-side GEM-63XL booster was suffering an anomaly: the exhaust plume was broader than it should have been and it appeared that ignited propellants might have been escaping the SRB just above the engine bell. Then, roughly 37 seconds into the launch as the vehicle was about to commence its roll programme to pitch itself out over the Atlantic, and just before passing through clouds, the base of the right-side SRB disintegrated.

On emerging from the cloud, cameras revealed the damaged SRB now had a very “off-nominal” exhaust plume, with pieces falling away as the launch vehicle continued its ascent. And here is where the overall robustness of the GEM-63XL came into play and the superb flight avionics and capabilities of the Vulcan Centaur were demonstrated. Rather than simply unzipping and exploding, taking out the entire rocket, as might reasonably be expected with the rocket was entering and passing through “max Q”, the period when it faces the maximum dynamic stresses imposed on its structure during ascent, the GEM-63XL held together and continued to provide at least some semblance of thrust all the way up to the engine cut-off point.

Meanwhile, the Vulcan Centaur sense the asymmetric thrust pushing it off of its flight trajectory and commenced compensating for it by gimballing the two Blue Origin BE-4 engines of the first stage and adjusting their thrust. At the same time, the vehicle started looking downrange and recalculating flight parameters in order to achieve a successful orbital insertion for its upper stage and payload. This entirely automated response also included calculating the likely drop-zone for the two SRBs following separation as a result of the off-nominal performance of the right side SRB.

This actually resulted in the rocket “holding on” to the two SRBs for 20 seconds beyond their expected release time. In doing so, this pretty much ensured both SRBs had sufficient upward momentum to complete their ballistic trajectory and then fall back to the Atlantic Ocean without exceeding any downrange parameters. Similarly, the rocket performed a recalculation of the required burn time on its main engines, and for the same reason.

Thus, the two BE-2 motors ran for an additional 6-7 seconds beyond their designated cut-off time. This was enough to ensure the Centaur upper stage received the kick it needed and the first stage to also remain within the parameters of its specified descent trajectory into its targeted (and shipping-free) splashdown area. Once separated, the Centaur stage was able to light its motor and go on to deliver its mass simulator almost exactly in the centre of the “bull’s-eye” of its intended orbital track.

And that is a remarkable success, all things considered. Sadly it did not stop some SpaceX cultists proclaiming FAA “bias” against SpaceX because a) Vulcan has not been “grounded” following the “failure” and b) the FAA signalled no requirement for a Mishap investigation on the grounds that, despite the SRB issue, the vehicle performed precisely as called for within its flight plan, and at no time exceeded the limits of it launch license.

Obviously, the GM-63XL failure needs to be thoroughly investigated by Northrop Grumman (potentially with FAA oversight) and the causes understood together with any significant issues – if found – rectified. However, this in itself require a “grounding” of Vulcan Centaur nor does it illustrate any kind of “bias” towards SpaceX on the part of the FAA. Why? Firstly, because the conflict between SpaceX and the FAA relate pretty much to the later exceeding the limitations imposed in the launch licenses issued to it by the latter. That’s not the case with the Vulcan Centaur flight.

More to the point, Vulcan Centaur’s launch cadence is fairly relaxed; the next launch will not occur until mid-November, for example. Ergo, there is more than enough time for the SRB issue to be investigated and a decision taken as to whether there is any kind of fault endemic to the GEM-63XL which precludes further Vulcan Centaur launches until such time as the problem has been rectified, and without the need for the FAA weigh-in on the matter pre-emptively.

Voyager 2 Loses Further Science Instrument

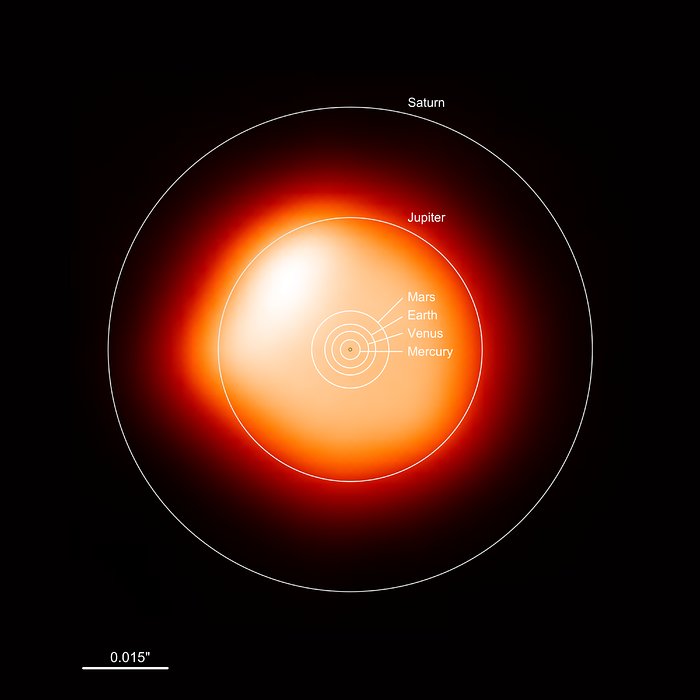

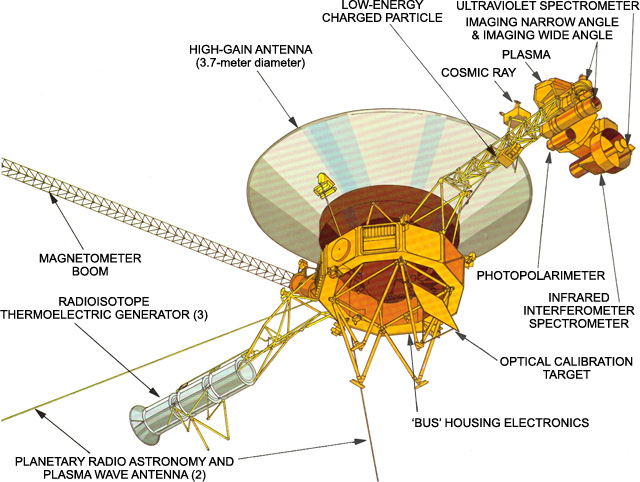

The two Voyager mission spacecraft have been hurling themselves away from Earth since their launches in 1977. In doing so, they are the first human-made craft to reach interstellar space, and are truly voyaging into the unknown. But even though both are powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) – essentially “nuclear batteries” generating electricity through the decay of plutonium 238 – their ability to produce the electricity they need to operate is constantly declining.

At launch the three RTGs on each of the Voyager vehicles generated some 470 watts of electrical power on a continuous basis. However, by 2011, that had been reduced to just 268 watts per vehicle. To combat the loss of electricity production NASA has, since 1998, been gradually turning off systems and instruments that are no longer essential to either vehicle’s mission.

For example, in 1998, NASA turned off the imaging system on the two spacecraft because the amount of light reaching them was insufficient for them to be able to produce meaningful images. Over time, this policy has continued to the point were, at the start of October 2024, of the 11 instruments aboard each of the vehicles, Voyager 1 had just four operating and Voyager 2 had just five, all dedicated to examining the interstellar space through which both vehicles are travelling.

However, on October 2nd, 2024, NASA announced that a further instrument on Voyager 2, the Plasma Spectrometer, has now been turned off, again to meet the dwindling amount of energy the RTGs are producing. This means that both craft are now operating the same four instruments each, allowing for solid comparative science to be carried out as they continue to move out into interstellar space. These instrument comprise a magnetometer gathering data on the interplanetary magnetic field; a low energy charged particle instrument for measuring the distributions of ions and electrons in the interstellar medium; a cosmic ray system that determines the origin of interstellar cosmic rays; and a plasma wave detector.

Unfortunately, overall power issues mean that the rate at which instruments must be turned off is likely to accelerate over the next few years, and that by 2030 it is likely the last science instrument on both Voyagers will be turned off, although there may be sufficient power for the communications systems to continue to transmit system reports beyond that, if NASA opt to allow them. But even if this is the case, by 2036, the signals from the two spacecraft will be so weak, they will not be heard by facilities on Earth.

But the loss of communications, when it eventually comes, will not be the end of the voyage for either of the spacecraft: in 300 years they should reach the “inner edge” of the theorised Oort cloud. It will take each of them some 30,000 years to cross it and arrive at the cosmographic boundary of the solar system. Ten thousand years after that, Voyager 2 will pass “just” 1.7 light-years away from the first star relatively close to its trajectory since departing the Sun: Ross 248. At roughly the same time, Voyager 1 will pass within 1.6 light-years of the star Gliese 445.

If you want to keep abreast of the Voyager mission status then check the official “where are they now” page for the mission.