ISS Updates

In a further sign that the International Space Station is in its final decade of operations, NASA is seeking to extend the current contracts for re-supply missions to the station from the period January 2027 through December 2030, in what is referred to as a “final” contract period.

In March 2022, NASA awarded additional contracts for ISS re-supply missions through until the end of 2026 to SpaceX (Cargo Dragon) Northrop Grumman (Cygnus) and Sierra Space (Dream Chaser Cargo). Under the extension, all three companies will be allowed to bid on remaining re-supply mission slots through until December 2030, but contract opportunities will not be issued to additional companies beyond these three.

Under the current contract, SpaceX are required to fly a total of 15 resupply missions through until the end of 2026, at an average of US $157 million per flight; Northrop Grumman 14 Cygnus flights at an average of US $150 million; and Sierra Space three Dream Chaser Cargo flights at US $367 apiece. It is not clear if any additional flights granted between January 2027 and December 2030 will be at the current rates or whether the three companies will seek to raise their fees – with the 2018 contract extension, SpaceX hiked their fees by 50%.

No further re-supply missions to ISS to be scheduled beyond 2030, that is the year the station is to be decommissioned and the majority of it de-orbited to burn up in the atmosphere, with any surviving elements crashing into the Pacific Ocean at Point Nemo – the area of that ocean furthest of land in any direction. However, modules due to be delivered to the ISS by Axiom Space starting in 2025 will be detached to form the nucleus of a new private-sector space station.

Currently, it is not clear whether Russia plans to remain with the ISS programme through until 2030 or withdraw some time before. In 2022, the country announced plans to withdraw “after 2024” (which many pundits took to mean “from 2025”) in order to focus on a national space station – the Russian Orbital Service Station. The power module for this new station had originally been slated for 2024, with the core module targeting 2025. However, the power module will now not launch before 2027, and the core module “no earlier” than 2028, so it would seem likely Russia will remain engaged in ISS operations through until at least then.

In the interim, there was a degree of excitement aboard the ISS in the past week. At 12:42 UTC on Monday, March 6th, 2023, the ISS has to use the thrusters on the Progress M-22 re-supply vehicle currently docked at the station’s Zvezda module to avoid a potential collision with an orbiting satellite.

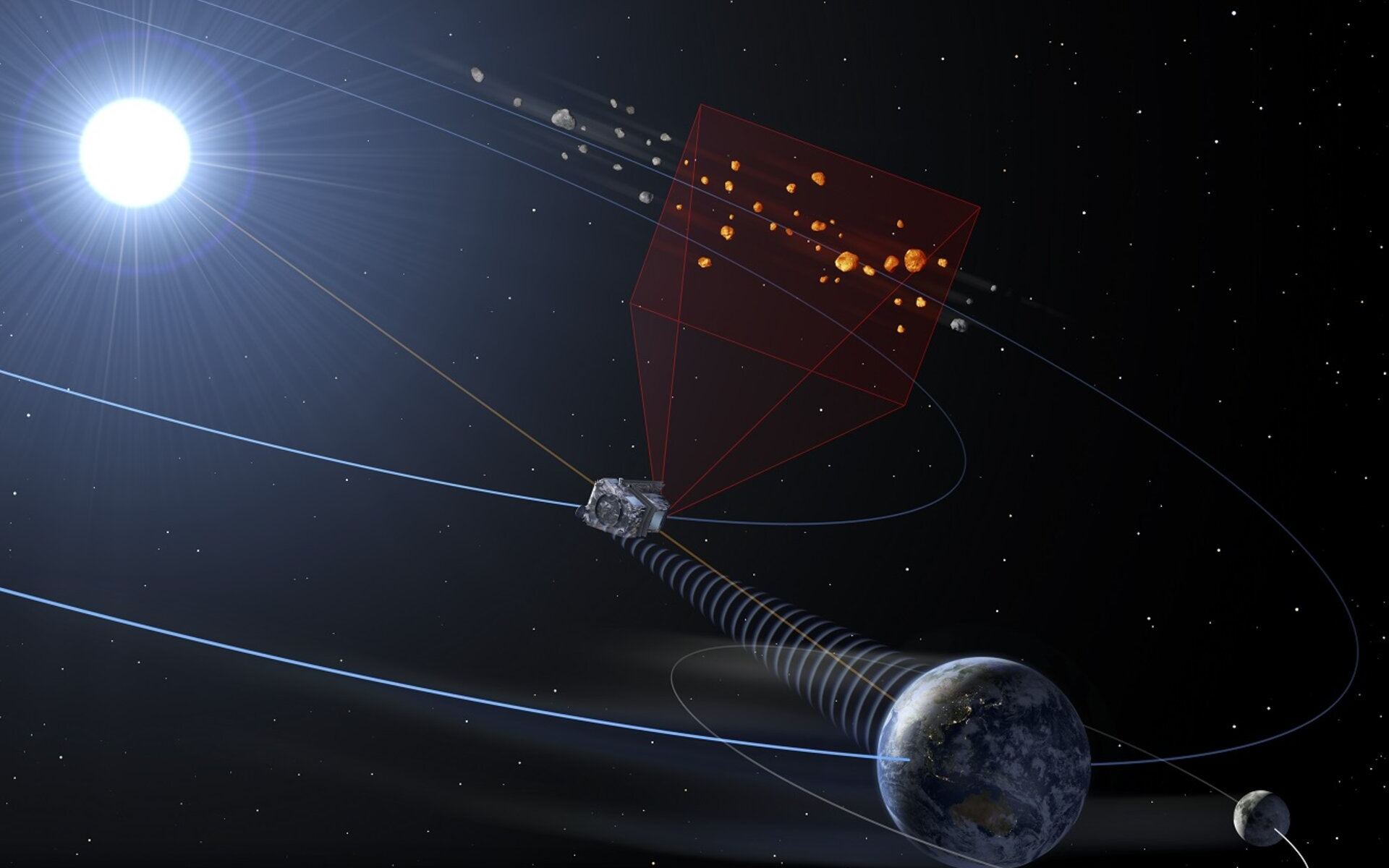

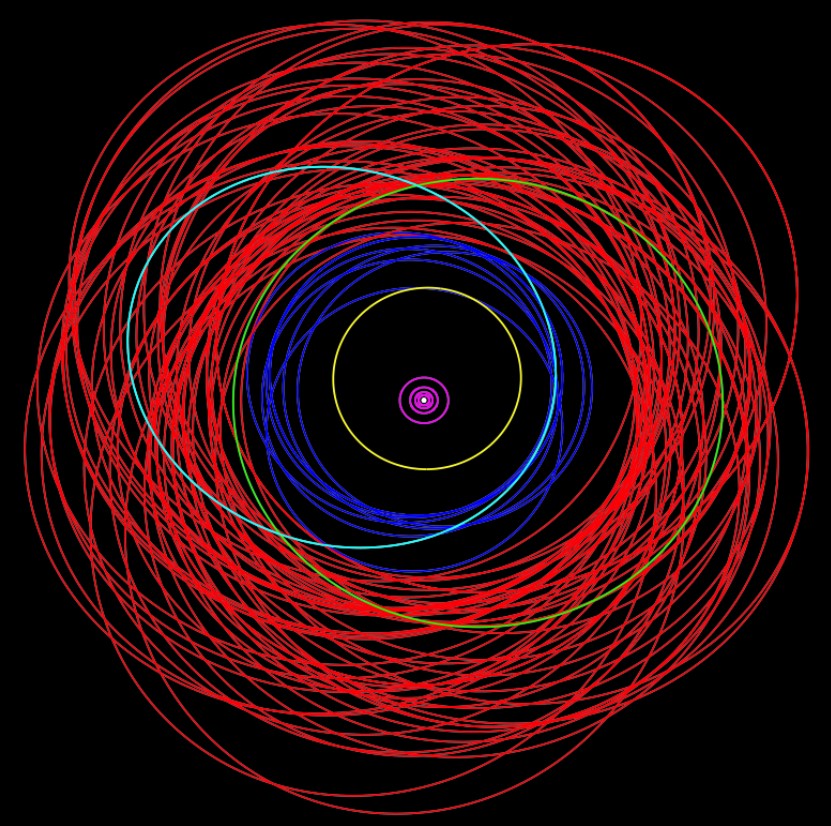

The satellite in question – believed to be Nusat-17, part of an Argentinean earth observation constellation, the majority of which were launched in the 2020s, and all ten satellites in the network are in orbits deteriorating towards that of the ISS. The potential for collision was known in advance, allowing the orbital boost – called a pre-determined avoidance manoeuvre (PDAM) – to be completed with the minimum of fuss, the Progress firing its thrusters for 6 minutes and without disruption to overall ISS operations.

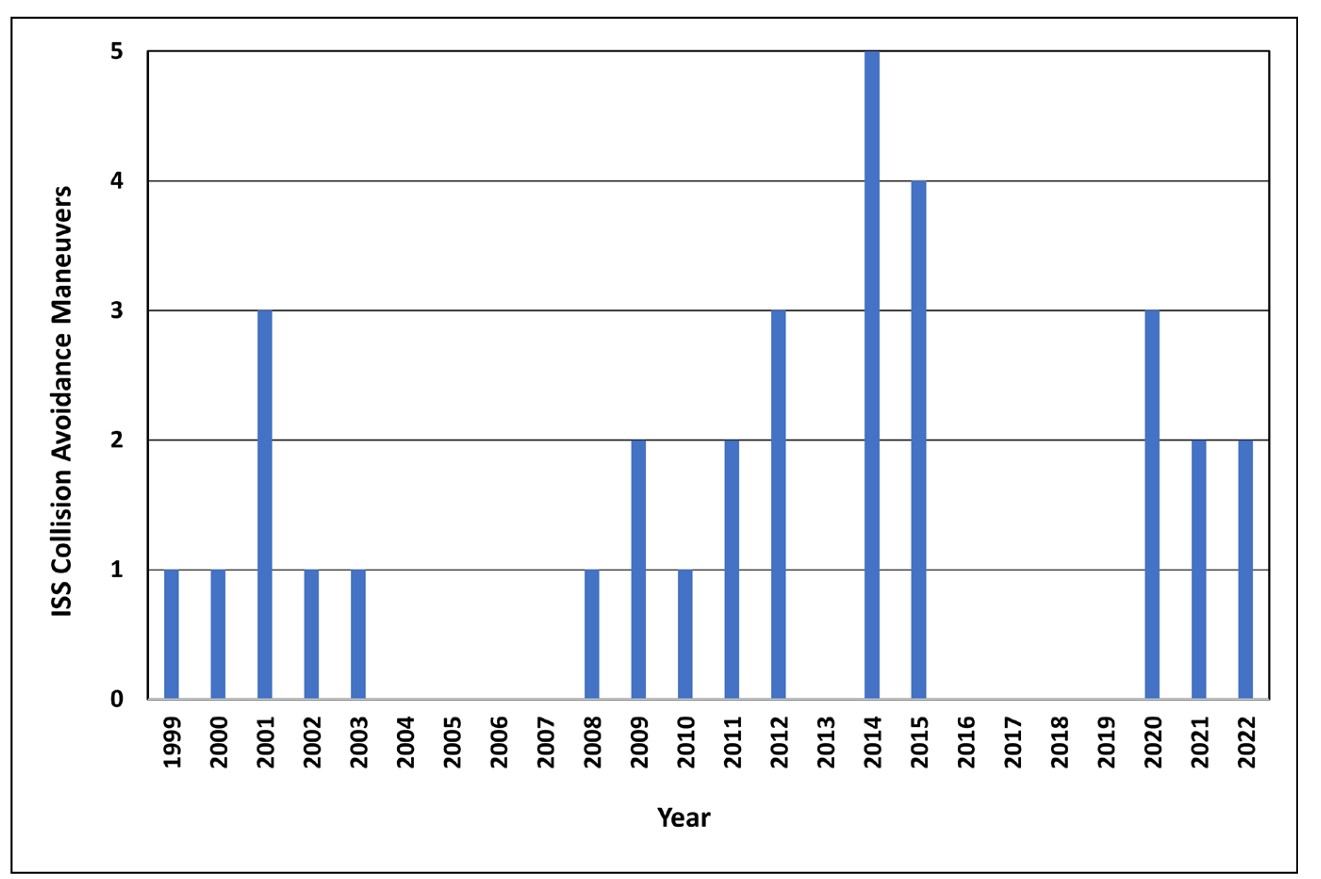

The manoeuvre marked the 33rd such change to the station’s orbital track resulting from the risk of collision since 1999, and there is mounting concern that the greater use of low-altitude constellations of satellites such as those operated by SpaceX Starlink and the UK’s OneWeb could see the ISS facing greater exposure to potential collisions over the next 7-8 years.

The distraction of the manoeuvre was not enough to delay preparations for the return of NASA’s Crew 5 mission from the ISS aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon Endurance, with the vehicle departing the ISS on Saturday, March 11th, 2023 at 0720 UTC. Aboard were NASA astronauts Josh Cassada and Nicole Mann, together the Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata and cosmonaut Anna Kikina of Russia, returning home after 157 days on-orbit aboard the ISS, and having completed a hand-over to the personnel of Crew 6, who arrived at the ISS on March 3rd.

After undocking, Endurance performed a series of orbital manoeuvres throughout the day, prior to completing re-entry to splashdown off the Florida coast at 02:02 UTC on Sunday, March 12th, bringing to an end a mission marked by firsts: Mann being the first Native American to reach orbit; Kikina the first Russian national to fly on a private US space vehicle, and Wakata setting the record for the longest cumulative time a Japanese astronaut has spent in space thus far – 505 days in total. He is also the only Japanese astronaut to fly into space in three different space craft: the US space shuttle (4 times), Soyuz (once) and Crew Dragon (once).

The Russian space agency Roscosmos is turning its eyes to the that the recent coolant leaks which left the crew of Soyuz MS-22 without a ride back to Earth and also affected Progress MS-21 towards a manufacturing fault.

Russian mission managers initially blamed a micrometeoroid strike on the leak which crippled Soyuz MS-22 on December 14th, 2022. However, when the Progress vehicle (referred to as Progress 82 by NASA) suffered a similar, but lesser rupture in its coolant loop, questions started to be asked as to whether something else was to blame – the Soyuz and Progress vehicles are essentially the same vehicles using the same systems, with the exception that Progress had none of the crew facilities or life support systems, instead being equipped for carrying cargo; they are also without any heat shield, so the entire vehicle burns-up on re-entering the atmosphere.

With Progress MS-21, Roscosmos stated the leak, which occurred in February, was the result of a launch incident five months before the vehicle docked with the ISS. However, Roscosmos has now joined with Soyuz / Progress manufacturer Energia to investigate a possible manufacturing issue affecting both vehicles – particularly given the failures occurred after both craft had been in space for roughly the same amount of time, suggesting some form of related failure.

As I noted in my previous Space Sunday update, Soyuz MS-22 has been replaced at the International Space Station (ISS) by MS-23, which is intended to provide the crew of Frank Rubio (NASA) and cosmonauts Sergey Prokopyev and Dmitry Petelin with a ride home in September 2023. However, NASA in particular is monitoring it and Progress MS-22 (launched in February 2023) for any signs of problems as the vehicles remain at the station.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: space stations, Vulcans, rockets”