It is perhaps the unsung hero of space launch capabilities. Whilst the media focuses on its darling Falcon 9 – a vehicle which, to be sure, is innovative, successful and highly flexible -, or reflects on Russia’s veritable (if sometimes troublesome) Soyuz family, Europe’s Ariane 5 has quietly gone about the business of lifting payloads to various orbits and a deep space missions for 28 years, barely coming to prominence in the news, unless in exceptional circumstances. Such as on the occasion of its final flight, as has been the case this past week. This is a shame, because the Ariane 5 project has been remarkably successful.

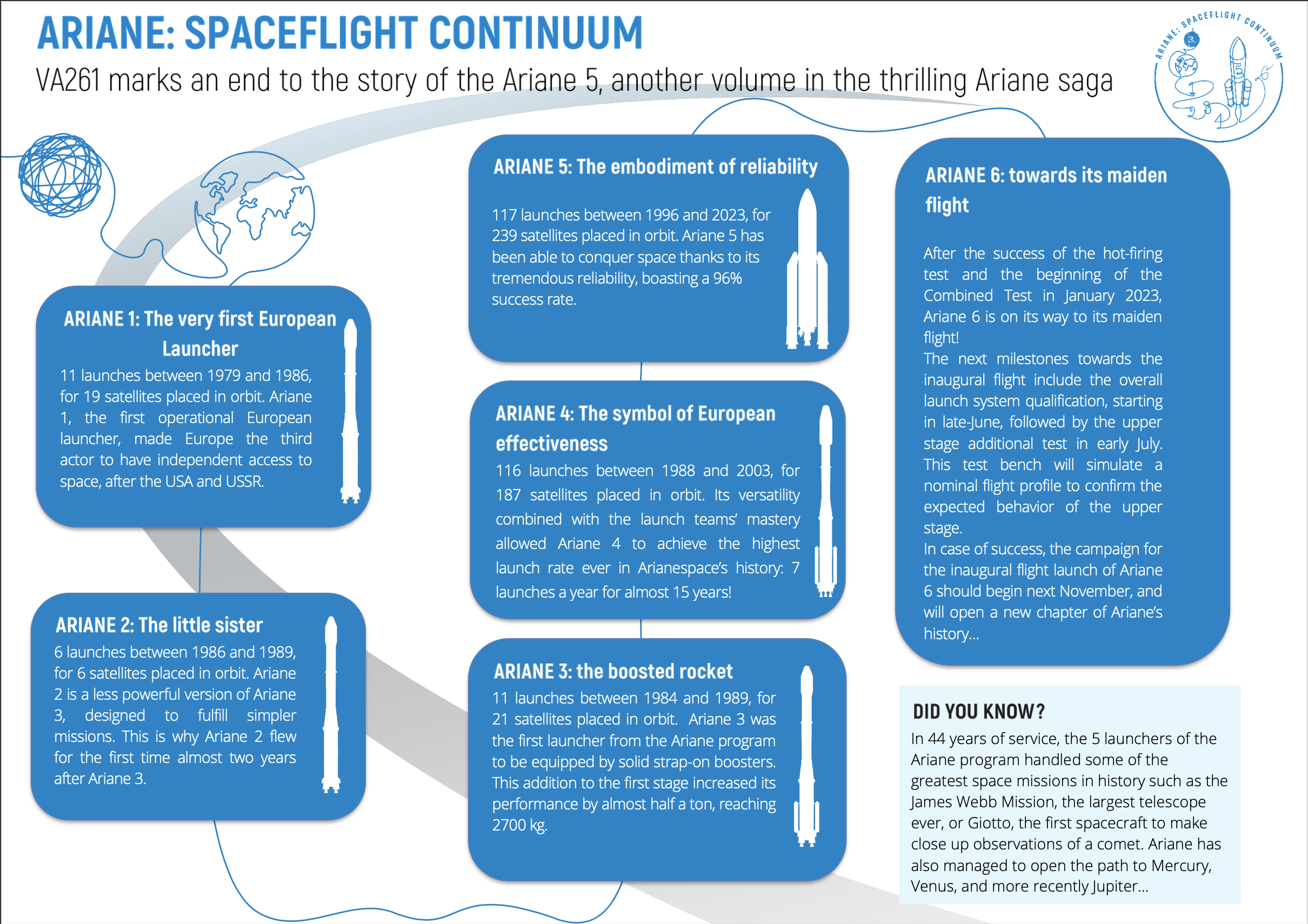

First flown in 1996 as the latest iteration of the Ariane family, the rocket’s history goes back to the 1970s, when an Anglo-French-German project was established to develop a new commercial launch vehicle for Western Europe. Christened “Ariane” – the French spelling of the mythological character Ariadne – the project became largely French-driven but within the auspices of the European Space Agency (ESA). The latter charged Airbus Defence and Space with the development of all Ariane vehicles and all related testing facilities, whilst CNES, the French national space agency, spun-up a commercial operation called Arianespace – in which they retain around a 32.5% stake – to handle production, operations, marketing and launches of the Ariane family, the latter being made out of Europe’s Spaceport, aka the Guiana Space Centre at Kourou in French Guiana.

Arianespace was the world’s first commercial launch provider, initially offering customer launches atop the evolving family of Ariane vehicles, commencing with Ariane 1 in 1979. Then, from 2003 through 2019, then partnership with Russia to provide medium-lift launch capabilities utilising the Soyuz-ST payload carrier under the Arianespace Soyuz programme, becoming the only facility to operate Soyuz vehicles outside of Russia (until the latter’s invasion of Ukraine brought the partnership to an end). In 2012, Arianespace further supplement its range of capabilities by adding the Italian-led Vega small payloads vehicle to their launch vehicle catalogue.

Ariane 5 was first launched in June 1996 in what was called the G(eneric) variant, capable of lifting 16 tonnes to low Earth orbit (LEO) or up to 6.95 tonnes to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). Over the coming years, it iterated through four evolutions – G+, GS, ECA, and ES – each bringing about a range of performance and other improvements which raised the vehicle’s maximum lift capabilities to 21 tonnes of payload to LEO and 10.86 tonnes to GTO whilst also allowing Arianespace to lower launch fees to customers. In addition – and while it was never used in such a capacity – Ariane 5 is the only member of the Ariane family to be designed for crewed launches, in part being designed to carry the Hermes space plane to orbit (of which more below).

In all, Ariane 5 flew a total of 117 launches from 1996 onwards, suffering three partial and two complete failures to deliver payloads as intended, with an maximum launch cadence of 7 per year. Notable among these launches are:

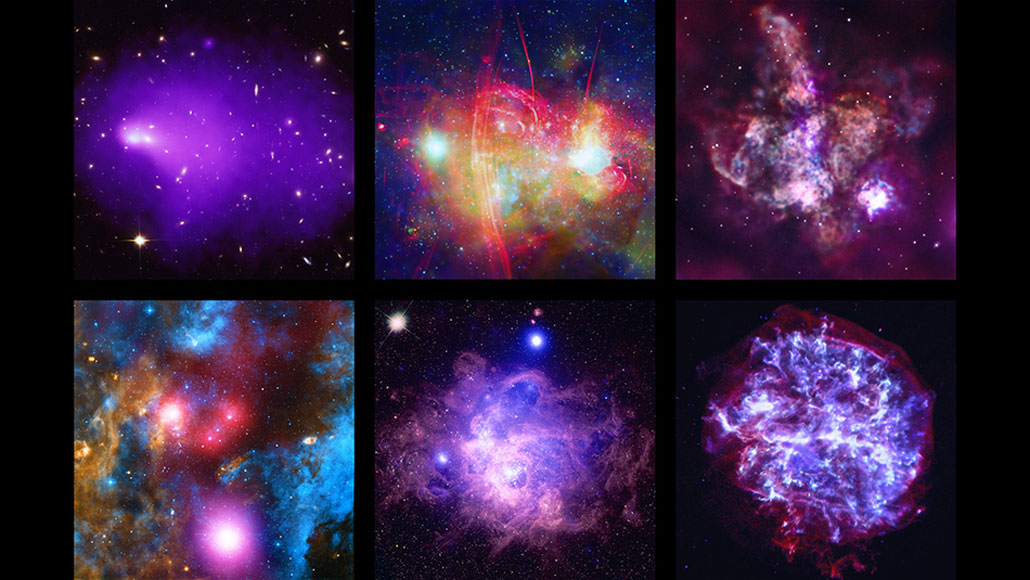

December 10th, 1999: the X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission (XMM-Newton). Itself an oft-overlooked mission when compared to NASA’s Great Observatories programme, XMM-Newton was one of the four “cornerstone” missions of the Horizon 2000 chapter of ESA’s science missions.

Named for English physicist and astronomer Sir Isaac Newton, the spacecraft comprises 3 X-ray telescopes feeding a range of science instruments and imaging systems. Its primary mission is the study of interstellar X-ray sources in both narrow- and broad-range spectroscopy, and performing the first simultaneous imaging of objects in both X-ray and optical (visible + ultraviolet) wavelengths. The programme was initially funded for two years, but its most recent mission extension will see it funded through until the end of 2026 – with the potential (vehicle conditions allowing) – for it to be extended up to the launch of its “replacement” mission, the Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics (ATHENA), due to commence operations in 2035/6. As of May 2018, XMM had generated more than 5,600 research papers.

March 2nd 2004: Rosetta. Another Horizon 2000 “cornerstone” mission, Rosetta spent 10 years using the inner solar system to allow it to rendezvous with the nucleus of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko – the first space vehicle to enter orbit around a comet following its arrival on August 6th, 2014.

For two years, the vehicle revealed an enormous amount about the comet, although it was perhaps overshadowed in the public consciousness by the adventures of the little Philae lander Rosetta dispatched to the surface of the comet, and which captured hearts and minds with its struggles.

May 14th, 2009: Herschel Space Observatory and Planck Observatory. These two ground-breaking missions were delivered to the Erath-Sun Lagrange L2 position (yes, the one also used by the James Webb Space Telescope – JWST -, and the one the Euclid mission will utilise where it arrives in an extended halo orbit around it in August 2023). Whilst separate missions, both spacecraft were launched on the same Ariane 5 booster and each utilised a service module built to a common design.

Initially planned for a 15-month primary mission, Planck – named for German physicist Max Planck – ran for just under 4.5 years, concluding in 2013 after on-board supplies of liquid helium were exhausted, and the primary instruments could longer be cooled to their required operating temperatures. As fuel remained for the craft’s manoeuvring thrusters, Planck was ordered to move away from the L2 position and into a heliocentric orbit, where its systems were decommissioned and the vehicle shut down.

The Herschel Space Observatory, meanwhile, operated for just over 4 years, and was the largest infrared telescope ever launched until the James Webb Space Telescope. It was yet another “cornerstone” mission for Horizon 2000, and was named for Sir William Herschel, the discoverer of the infrared spectrum. Its primary objectives comprised investigating clues for the formation of galaxies in the early universe, the nature of molecular chemistry across the universe, the interaction of star formation with the interstellar medium and, closer to home, the chemical composition of atmospheres and surfaces of planets, moons and comets within our solar system. In this regard, the observatory amassed more the 25,000 hours of science data used by 600 different science programmes.

October 20th, 2018: BepiColumbo. Undertaken by ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), BepiColumbo is the overall mission title given to two vehicles and their transfer bus, all launched as a “stack” via Ariane 5, in a mission to carry out a comprehensive study Mercury, the innermost planet of the solar system. It is named after Italian scientist and mathematician Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo.

Despite its orbit being relative close to Earth (when compared to the outer planets of the solar system that is), Mercury’s is one of the most technically complex to reach. “Bepi” Columbo calculated a vehicle could use a solar orbit and multiple fly-bys of the inner planets to reach Mercury in an energy-efficient manner – and it is this style of approach the mission is using to reach its destination. It has already completed five gravity assist manoeuvres (1 around Earth in 2020, two around Venus in 2020 and 2021 and 2 around Mercury in 2021 and 2022). A further fiver fly-bys of Mercury will occur in 2024/25 to bring the mission to its primary science orbit around the planet at the end of 2025.

At that time the vehicles will separate, the transfer bus, called the Mercury Transfer Module being discarded to allow the 1.1 tonne ESA-built Mercury Planetary Orbited (MPO) to commence what is expected to be at least one terrestrial year of operations studying the planet. During the initial phase of this mission, MPO will in turn deploy the Japanese-built Mio vehicle into its own orbit around Mercury, where it is also expected to operate for at least a terrestrial year.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: saying adieu to Ariane 5 and recalling Hermes”