For the last few years, and as news arises, I’ve been covering the ambitious plans developed by a team at the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) of Johns Hopkins University (JHU) to send a flying rover vehicle to Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

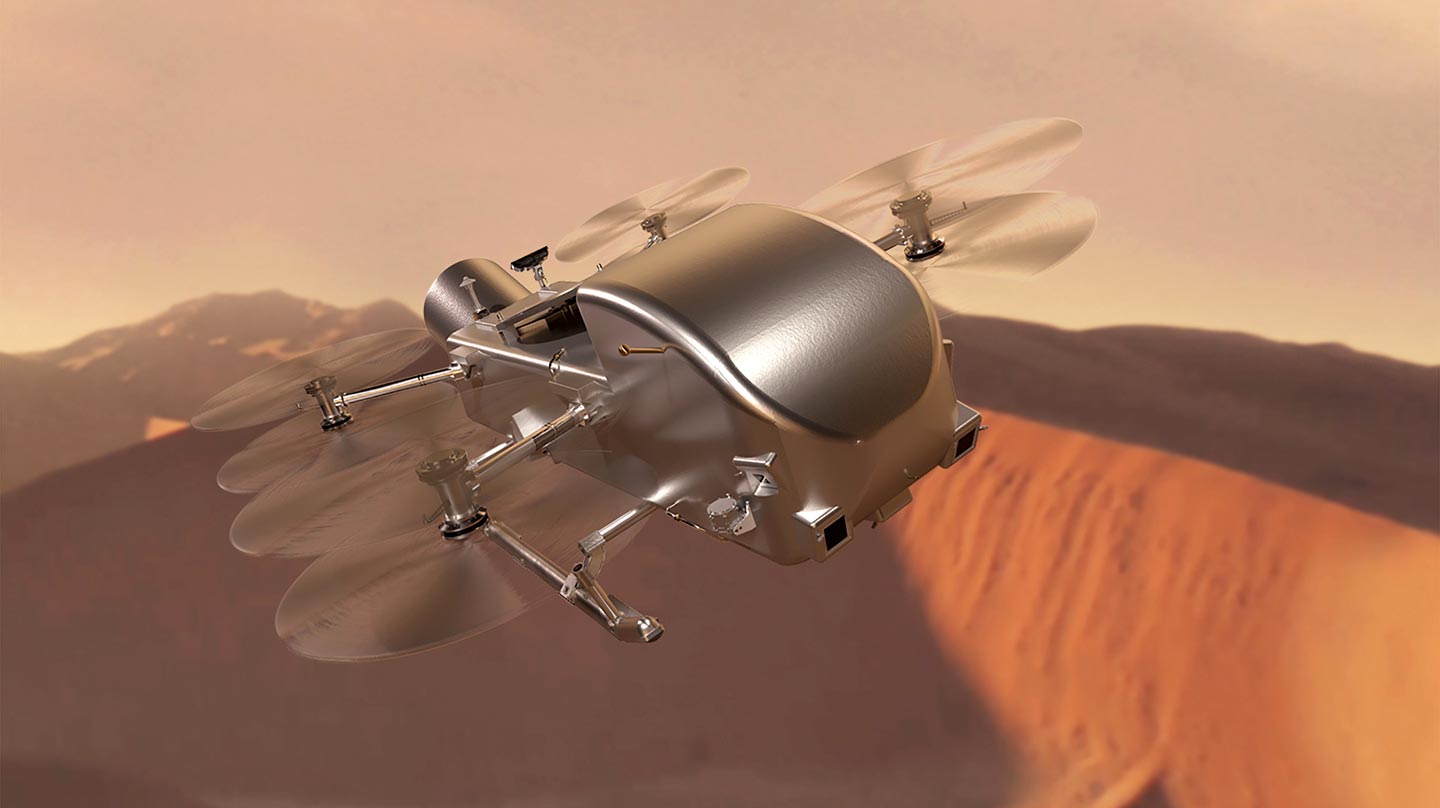

The mission, using a octocopter called Dragonfly has been in development for several years, being formally greenlit for full-scale development by NASA earlier in 2024 (see: Space Sunday: flying on Titan; bringing home samples from Mars), after initially selecting it for evaluation and conceptual development as a part of the space agency’s Frontiers programme in 2019.

The idea of sending a flying – or at least floating, as proposals have also included the potential use of balloons to explore Titan from within it dense atmosphere – has been around for some time. In fact, Ralph Lorenz, of JHU/APL, one of the proposers of the mission, first considered using rotary craft on Titan back in 2000. His idea then was to use a battery-powered rotor craft equipped with a radioisotope power source.

That vehicle would spend the daylight hours on Titan (equivalent to 8 terrestrial days) in flight or carrying out surface science. during the hours of darkness (again, lasting the equivalent of 8 terrestrial days), the vehicle would sit on the ground and use the radioisotope to both keep itself warm and recharge the batteries.

It is to this idea that Lorenz returned whilst having dinner with Jason W. Barnes of University of Idaho in 2017, with the two of them agreeing to work on a baseline proposal for a large rotorcraft capable of flying on Titan. Together, they formed a nucleus of a team of scientists largely from APL’s staff of space scientists, including Elizabeth “Zibi” Turtle, who would be the mission’s principal investigator, as well as expertise from both NASA and other universities and space science institutes such as Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS), another long-time NASA partner.

Their initial proposal was published in 2018, and pretty much laid out the entire concept. Put before NASA for consideration, the proposal went through a series of changes prior to acceptance as a Frontiers mission. Initially targeting a 2027 launch, the mission was hit (like most things) by the COVID 19 pandemic, with all parties agreeing to push back the launch until July 2028.

These delays actually pushed the Dragonfly mission outside of the parameters of the Frontiers guidelines – missions under its auspices are supposed to be developed and flown for no more that US $1 billion (including all launch operator costs); currently, Dragonfly is expected to hit a total cost of around $3.35 billion throughout its lifetime. In all, the primary mission is expected to last some 10 years, 3.3 years of which will by at Titan.

But why go so far and at such cost in the first place? Well, as I noted back in April:

Titan is a unique target for extended study for a number of reasons. Most notably, and as confirmed by ESA’s Huygens lander and NASA’s Cassini mission, it has an abundant, complex, and diverse carbon-rich chemistry, while its surface includes liquid hydrocarbon lakes and “seas”, together with (admittedly transient) liquid water and water ice, and likely has an interior liquid water ocean. All of this means it is an ideal focus for astrobiology and origin of life studies – the lakes of water / hydrocarbons potentially forming a prebiotic primordial soup similar to that which may have helped kick-start life here on Earth.

As both the Huygens lander and Cassini probe showed, Titan is similar to the very early Earth and can provide clues to how life may have arisen on Earth; it is also an aerodynamically benign world. Its dense atmosphere (around 1.45 times that of Earth’s) is ideally suited to the use of rotary vehicles – considered superior to balloons, dirigibles and aircraft because their ability to hover in place whilst carrying out ground observations and their VTOL (vertical take-off and landing) capabilities mean that can easily set down for surface science activities / at the onset of night. Further, Titan has low gravity (around 13.8% that of Earth) and little wind, making automated flight a lot easier.

Most crucially of all, flight allows the vehicle to move with relative ease between locations of interest for study, even if they are geographically widespread, separated by distances (and potential obstacles) a surface rover might find insurmountable.

Of course, we’re all now familiar with the idea of helicopter drones flying on other worlds, courtesy of NASA’s plucky little Ingenuity on Mars. However, The Dragonfly vehicle is something else all together. For a start, it is the size of a small car, and is expected to have an all-up mass of around 450kg. A good portion of that will be taken up by its Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), its large lithium-ion battery system and its four electric motors, each driving two pairs of 1.4 metre diameter contra-rotating rotor blades. When flying, the vehicle will be able to reach speeds of up to 36 km/h, with a maximum airborne time of 30 minutes at that speed.

Obviously, given the distances between Earth and Saturn / Titan render two-way real-time communications impossible without considerable lag, the vehicle will be equipped with a fully autonomous flight and navigation system capable of flying it along a selected flight path, making its own adjustments to account for local conditions whilst in flight, and with sensors capable of recording potential points of scientific interest along or to either side of its flight path, so the information can be relayed to Earth and factored into planning for future excursions. Flights over new terrain will likely be of an “out and back” scouting nature, the craft returning to its point of origin, allowing controllers on Earth to plan follow-up flights to locations where they might wish to set down and carry out ground-based science studies.

In terms of the latter, the vehicle will carry a number of science instruments, including two coring drills and hoses mounted within is landing skids, allowing it to gather tailings from the moon’s regolith and surface for on-board analysis by the vehicle’s on-board laboratory.

Most recently, as well a working on the full-scale development of the vehicle, APL has also been carrying out further tests with a half-scale flight-capable model, which has been used for the last year to help test and refine flight systems and avionics. This has seen the vehicle put through its paces at near-to-ground flight tests and at reasonable altitudes (but not as high as the four kilometres maximum ceiling the full-size version is expected to operate at during deployment!

In particular, this works builds on work carried out inside a special wind tunnel at NASA’s Langley Research Centre during 2023, which was used to simulate the aerodynamic loads that would likely be placed on the vehicle’s rotors and motors during a wide range of flight operations – ascending, descending, hovering – allowing engineers to determine things like the amount of rotor pitch required during different types of flight operations, providing data which can be fed into the final design requirements for the actual vehicle.

Much of this testing has been around flight hardware redundancy – APL plan to have the vehicle capable of sustained flight even if one set of rotors fails or even a motor supplying power to two sets of rotors dies. These tested have also allowed for direct assessment of the vehicle’s handling and determining where the centre of mass / centre of gravity should be placed (remembering that the drum-like thing at the back of the vehicle is a nuclear generator and all its associated shielding) to ensure good flight handling across a range of dynamic flight situations.

Also, on November 25th, 2024, NASA confirmed that SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch vehicle will be used to send Dragonfly on its way to Saturn. This caused some mis-reporting (notably among SpaceX fans) that the mission is somewhat a NASA / SpaceX venture, or has only been made possible by SpaceX, with some SpaceX-biased commentators going to so far as to call the decision “unexpected”. However, Falcon Heavy is the only launch vehicle currently certified for launching NASA high-value missions – particularly those carrying an MMRTG; United Launch Alliance (ULA) having retired both of its certified launch vehicles – Atlas and Delta – and have yet to achieve the required NASA certification with their Vulcan-Centaur (as is the case with Blue Origin’s New Glenn). As such, and with the prohibitive cost of using NASA’s own SLS rocket, Falcon Heavy has been the only real contender for the job.

At a cost of US $256.6 million, the contract to launch Dragonfly is significantly more than the $178 million NASA paid for the launch of the equally complex Europa Clipper, and the $117 million for the launch of the Psyche mission (although admittedly, that was agreed in 2020), both of which utilised Falcon Heavy. What was new with the announcement was the selected launch window and flight trajectory. The mission is slated to launch some time between July 5th and July 25th, 2028 (inclusive), in a window that will require the vehicle to make a fly-by of Earth in order to acquire the velocity required to reach Saturn in 2034. In this, the flight does differ from the originally planned 2027, which would likely have included a flyby of Jupiter, rather than Earth; however, for the 2028 launch, Jupiter will not be in a position to provide a gravity assist, hence the use of Earth, marking the mission as the first dedicated mission to the outer solar system to not use Jupiter in this way.

Progress MS-29 Update

In my previous Space Sunday update, I covered the detection of a “toxic smells” within the Russian section of the International Space Station (ISS), requiring the atmosphere throughout the station to be scrubbed. The first outlet to cover the news – as it was breaking – was the highly-reliable Russian Space Web, operated by respected space journalist and author, Anatoly Zak, and it was through that source I first read of the situation.

During the past week other outlets have taken up the story, but it is Anatoly who continues to lead with updates. While there was no immediate danger to any of the ISS crew, the hatches to the Progress vehicle were sealed and the atmosphere throughout the station scrubbed – on the international side of the station, the use of the Trace Contaminant Control Sub-assembly (TCCS) system was imitated after NASA astronaut Don Petit reported a “spray paint-like” smell in the Node 3 module of he station.

In Anatoly’s most recent update in the story, he confirmed that after recycling the atmosphere in the Progress vehicle, the hatches had been reopened between it and the Poisk module against which its docked and off-loading of supplies had commenced. Anatoly also noted the the current working hypothesis from Roscosmos is that the smell did not originate from within the Progress MS-29 vehicle.

Instead, the Russian space agency believe the smell came from within the docking mechanism on the Poisk module. The Russian docking mechanisms include fuel lines for both off-loading hypergolic propellant supplies from a newly-arrived resupply vehicle carrying them, and to transfer propellants to Soyuz vehicles to “top off” the tanks of their thrusters prior to making a return to Earth.

Because of this, and while docking operations involving Progress and Soyuz are automated, after any departure from the Russian section of the ISS, ground control should perform a purging of the inner chamber of a docking mechanism to ensure any leak of hypergolic propellant that have been in the feed lines at the time which might otherwise be contained within the chamber is removed. This appears not to have been done following the departure of the last vehicle to use this particular docking port, Progress MS-27, potentially leaving traces of highly toxic propellant caught between the newly-arrived MS-29 and the interior of the Poisk module, releasing them into the latter when the inner hatch was opened.