Billionaire Jared Isaacman was confirmed by the US Senate as NASA’s new Administrator under the Trump administration – more than half a year after his appointment had originally been expected. The delay in the confirmation was the result of Trump himself, who withdrew Isaacman’s nomination virtually on the eve of his initially expected confirmation, possibly as a result of Trump’s public falling-out with the CEO of SpaceX, with whom Isaacman has close ties.

Those ties were a cause of concern back in April 2025, and rose again in the December hearings on Isaacman’s re-nomination, with some within the Senate questioning how unbiased he might be when it comes to making decisions around NASA’s human space efforts – particularly with regards to the Artemis Programme. In particular, questions have been raised over Isaacman’s financial ties to SpaceX – a company he has twice used for private-venture launches which have seen him gain almost 8 days experience in orbit with two crews. Isaacman himself has remained opaque on his precise financial ties with SpaceX, stating NDAs prevent him being more candid, whilst offering – at least prior to his confirmation – to seek release from his obligations by SpaceX to disclose them.

Another cause for concern over her appointment lay in the form of the 62-page Project Athena document. Penned by Isaacman and his team earlier in the year, this outlined a radical direction for NASA which many saw as not particularly in the agency’s best interests. Within it, Isaacman pushes for various aspects of NASA’s research work to be handed over to the private sector whilst also seeking to continue the – contentious, as I’ve noted in these pages in the recent past – work of apparently winding down the many functions and much of the work of the Goddard Space Flight Centre (GSFC) by either transferring them (e.g. to the Johnson Space Centre) or “deleting” them.

Whilst there is nothing wrong with commercialisation where it can be carried out properly and with the right supervision, history has already shown that when it comes to R&D and development, it doesn’t always work out.

Boeing’s Starliner is perhaps the most identifiable case in point here, even allowing for the company having to absorb the majority of the cost over-runs; however, it also overlooks SpaceX, which remains the greatest benefactor of NASA funding with absolutely no return to the American taxpayer. Without NASA’s intervention in the early 2000s, SpaceX would have failed completely with the Falcon 1 rocket, NASA effectively covering the lion’s share of development costs associated with Falcon 9, and with both the Dragon and Crew Dragon vehicles.

For his part, Isaacman has continued to deflect from the Athena document, calling it a set of “ideas” and “thoughts” rather than an actionable plan – this despite the fact that a) it is actually entitled a “strategic plan” for NASA, and b) it lays down a pretty clear roadmap that is heavily biased towards commercialisation, even in areas where it is difficult to see commercial entities being willing to engage unless assured of significant government financing.

However, all of this might now by a side note in terms was to what happens at NASA next, given that on the very day Isaacman took up his new post at NASA, December 18th, 2025, Trump issued an executive order outlining much of NASA’s immediate future priorities – and in places, quite ironically so.

Trump’s New Executive Order for “American Superiority” In Space

Whilst not including anything Earth-shatteringly new, the December 18th executive order focus on four areas: expanding America’s human exploration of space, but with the focus confined to the Moon and Earth orbit; expanding America’s strategic and national security needs in space; “growing a commercial space economy”; and “developing and deploying” advanced technologies “to enable the next century of space achievements”.

Specifically with regards to NASA, the order calls for:

- Returning Americans to the Moon by 2028 via Artemis.

- Establishing the initial elements of a Lunar South Pole outpost by 2030.

- Enabling the use of nuclear power in Earth orbit and on the surface of the Moon.

- Further NASA’s reliance on commercial launch vehicles and providers.

- Streamline NASA’s procurement processes, again with a bias towards buying-in rather than in developing.

- Offset costs by decommissioning the International Space Station (ISS) in 2030, and moving to private sector space research and orbital facilities.

In addition, the Executive Order requires that in his first 90 days, Isaacman must submit a report on how the above – and other goals impacting NASA, such as financing commercial space activities – are to be achieved.

The goal of landing humans on the Moon by 2028 remains something of a reach. As was noted by Acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy – and despite the SpaceX CEO’s protestations otherwise – it is very hard to see the SpaceX Human Landing System – the vehicle needed to get crews from cislunar space to the surface of the Moon and back again – and its many complex requirements being anywhere near ready and fully tested by 2028.And while Blue Origin, with their slightly less complicated Blue Moon Mark 2 HLS apparently well ahead of the curve in terms of development – including active astronaut testing of various elements of the vehicle as well as having a launch vehicle proven to be able to reach Earth orbit with a payload in place – it is not without complexities of its own which could yet impact on its ability to overtake the SpaceX Starship-derived system.

Perhaps the biggest issue facing both of these vehicles is NASA’s own insistence that they use cryogenic propellants. This makes both vehicles massively more complex than the likes of the Apollo Lunar Lander, which used a hypergolic motor system and thus it required no complex turbopumps or other systems in its engines, and the propellants did not require an external ignition source (they would ignite on contact) and could be stored relatively compactly.

Cryogenic propulsion, whilst providing a potentially greater bang, does require more complex engines, an ignition source, and substantial storage as they are bulky. Ergo, for either of the two HLS systems NASA plans to employ, there exists a requirement to be able to “refuel” the HLS vehicle when on-orbit, with the SpaceX HLS requiring substantially more in the way of propellant reloading than Blue Moon.

Further, and as the name suggests, cryogenics propellants require very low temperatures in order to remain in a liquid state (essential for reducing their bulk and enabling their flow). That’s hard enough when on Earth; in space, where either HLS vehicle will spend much of its time in the full blazing heat of the Sun, it’s much harder.

Thus, for both HLS vehicles to work, SpaceX and Blue Origin must be able to develop and test a reliable system to transfer tonnes (hundreds in the case of SpaceX HLS) of propellants between craft, and develop a means to minimise potential boil-off and loss through gaseous venting of side cryogenics. Again, neither company is anywhere near achieving either of these milestones.

Establishing the elements of a lunar outpost by 2030 is at best an ambiguous goal within the executive order, in that no effort is made to expand on whether this means on the surface of the Moon or just in cislunar space, such as by the positioning of initial elements of the Lunar Gateway station.

Gateway is a further questionably element of Artemis, with critics pointing to the fact that it is not actually needed for any return to the Moon by America. And while NASA promotes it as a “command and control centre” for lunar operations and a potential “safe haven” in emergencies, the fact remains that it is anything but.

When deployed, the station will likely occupy a 7-day near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) around the Moon, making its closest passes (1,500 km altitude) over the lunar North Pole, and extending out as far as 70,000 km from the lunar South Pole, the area selected for surface operations, thus limiting its ability to respond to any surface emergency.

That said, the lack of any indicators as to what is meant in terms of a lunar outpost within the executive order does give Isaacman a relatively free hand with his response.

Similarly, the reference to the use of nuclear power is somewhat ambiguous. While there have been studies and proposals on using compact nuclear plants on the surface of the Moon (see: Space Sunday: propulsion, planets and pictures), nothing concrete has been put forward for Artemis, which gives Isaacman some room. However, in terms of propulsion systems (if these are included in the order’s reach), it is interesting to note that the joint DARPA-NASA DRACO project, which would have potentially seen a nuclear propulsion demonstrator flown in 2027, was cancelled earlier in 2025 because – irony – the Trump administration was looking to cancel it anyway under the 2026 budget proposal.

Looking to leverage more commercial launch services is something that fits with Isaacman’s Athena document, as mentioned above. Also as mentioned, there is nothing wrong with this if it s done right, but this is harder to achieve than might otherwise appear to be the case (again, note the comments vis Boeing / Starliner and SpaceX Starship), and too much reliance on commercial entities can led to delays and issues as much as seen with SLS, simply because commercial entitles can have their own goals and requirements which can come at a higher priority.

Again, part – not all, given the fubar over the Artemis space suits – of the fact that Artemis 3 slipped from a 2026 date to 2028 is down to SpaceX consistently failing to prove Starship can do what is promised of it. This includes statements from the company’s CEO that a Starship would fly around the Moon with a crew of 8 in 2023, and the HLS version would make an unscrewed demonstration landing on the Moon in 2024. As such, there is much to be cautious about when it comes to any off-loading of capabilities to commercial entities.

The ISS retirement is easier to rationalise. Like it or not, the entire structure is aging and much of it is passing its planned operational lifespan. Even the most recent large Russian module to join the ISS – Nauka, launched in 2021, started construction in the early 1990s, marking its core structure older than its planned operational lifespan of 30 years. But the Russian modules are not alone, the US Unity module was constructed in the 1990s and launched in 1998, and thus is sitting on top of its 30-year planned lifespan.

As such, while there is no reason much of the ISS could continue beyond 2030, it is not without increasing risks and / or rising issues. Thus, decommissioning it does, sadly make a degree of sense.

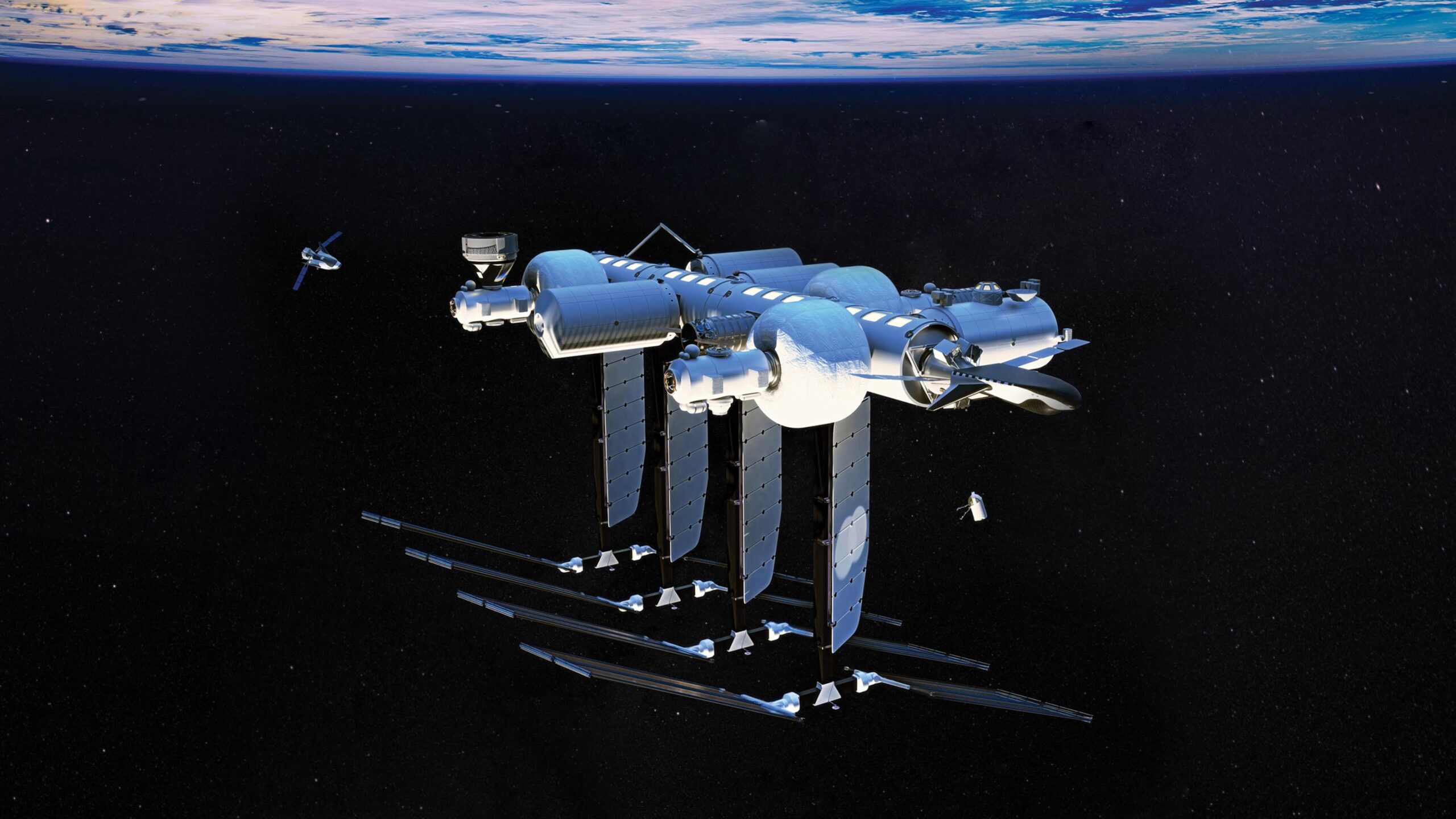

What does not make sense, however, is the failure to plan for any real replacement for it in Earth orbit and simply relying on “commercial entities” to continue the tradition of research and science established by the ISS. The latter, as a government operation, does not have to generate a return on investment and is ideally suited by its governing articles to be a centre of research and study. Commercial entities, however, will be driven by a need to be profitable – hence why, while there are a number of commercial space stations is development (take Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef as an example, being perhaps the largest), their focus leans far more towards orbital tourism, their operators intending them to become resorts in space for those who can afford a ticket. Using them as a centre of research sits some way behind this, and will not be without a range of its own costs, both in terms of getting to / from a station and in actually spending time aboard it, as well as the time researchers might be permitted to stay.

Another risk in ending the ISS and not supporting any form of replacement potentially undermines the Trump administration’s desire (and the concerns of Congress and the Senate) to curtail (or at least slow) China’s growing ascendency on the international stage. With the ISS gone, Tiangong will become the only large-scale and potentially expandable orbital research facility – thus it could become the hub of international space-based research.

Which is a long way of saying that Jared Isaacman has come into NASA at a time of potential turmoil and with a possible agenda which could do much to completely alter the agency. But whether this is to its betterment or not will have to be seen in time.