A little over a year ago, NASA released a statement on a find made by the Mars 2020 rover Perseverance as it continued to explore an ancient river outflow delta within Jezero Crater on Mars. It related to an unusual arrowhead-like rock NASA dubbed “Cheyava Falls”, and which showed both white veins of calcium sulphate – minerals that precipitate out of water – running across it, and tiny mineral “leopard spots”, whitish splotches ringed by black material.

These spots, together with black marks referred to as ”poppy seeds”, are common on Earth rocks when organic molecules react with hematite, or rusted iron, creating compounds that can power microbial life. “Cheyava Falls” was the first time such formations had been located and imaged on Mars, and marked the rock, roughly a metre in length and half a metre wide to become the target for more detailed study before the rover eventually moved on.

This study resulted in more discoveries hinting at the potential for organic processes to have perhaps once been at work within the rock, as I noted in Space Sunday: Mars Rocks and Space Taxis. However, the matter was complicated both because “leopard spots” can also be the result of an abiotic chemical reaction rather than the result of any organic interaction, and the further examination of the rock revealed the presence of olivine mineral.

The latter is no friend to organics, as it generally forms within magma at temperatures deadly to organic material. This suggest it and the phosphates and other organic-friendly minerals within the rock may have been deposited at temperatures which would have killed off any organics present long before they could have resulted in the “leopard spots” forming, leaving the latter’s formation purely a matter of inorganic reactions.

But the matter is complicated, and for all of its capabilities, the science laboratory aboard Perseverance is limited in how much it can do. What is really required is for the samples gathered from “Cheyava Falls” to be returned to Earth and subject to far more extensive study – something which in the current political climate in the United States, isn’t going to happen in the near-term.

Considerable caution needs to be taken when discussing matters of microbial life on Mars. The planet is a highly complex environment, and while there are many indicators that it may have once been a far warmer, wetter and cosier environment which may have formed a cradle for the basics of life, that period might also have been extremely brief in terms of the Mars’ very early history. And therein lies another twist with “Cheyava Falls”; the rock appears to have formed some time after that period in the planet’s history.

If nothing else, the likes of ALH84001 – the meteorite fragment discovered in the Allen Hills of Antarctica in 1984 and shown to have originated on Mars – encourage a lot of caution is required when it comes to trying to determine whether or not something is indicative of organic interactions having once been present on Mars.

In that particular case, the team studying the fragment in 1996 reported they may have found trace evidence of past microscopic life from Mars. Unfortunately, their findings were over-amplified by an excited press to the point where even in the face of increasingly strong evidence that what they had discovered – what appeared to be tiny fossilised microbes embedded in the rock – was actually the result of entirely inorganic processes, members of the science team involved in the ALH84001 study became increasingly adamant they had for evidence of long-dead Martian microbes. It wasn’t until around 2022 that the debate over this piece of rock was apparently settled (see: Space Sunday: pebbles, ALH84001 and a supernova).

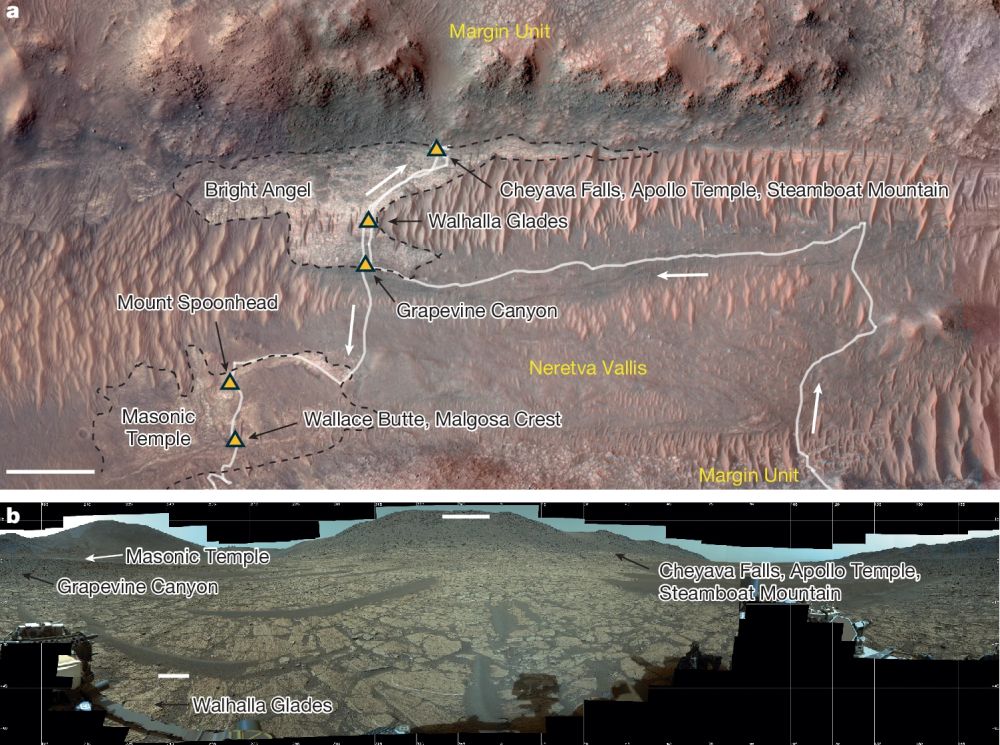

With this in mind, an international team set out to subject the data and images gathered from “Cheyava Falls” and its immediate surroundings, referred to as “Bright Angel”, and where other samples were taken for analysis by the rover, in an attempt to try to identify the processes at work which may have resulted in the formation of the “leopard spots” and “poppy seeds”. They published their findings on September 10th, 2025 – and those findings are potentially eyebrow-raising.

On Earth, all living organisms obtain energy through oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions, the transfer of electron particles from chemicals known as reductants to compounds named oxidants. An example of this is mitochondria found in animal cells which transfer electrons from glucose (a reductant) to oxygen (an oxidant). Some rock dwelling bacteria use other kinds of organic compound instead of glucose, and ferric iron instead of oxygen.

Ferric iron can be similarly reduced, resulting in water-soluble ferrous iron, which can be leached away or reacts to form new, lighter-coloured minerals, resulting in the “leopard spot” deposits very similar to those found on “Cheyava Falls”. In particular, these latter reactions can result in two iron-rich minerals, vivianite (hydrated iron phosphate) and greigite (iron sulphide). Again, on Earth the formation both of these minerals can involve organic interactions with microbes – and both vivianite and greigite appear to be present within the “Cheyava Falls” samples analysed by Perseverance.

However, as noted, above “leopard spots” – and by extension vivianite and greigite – can be formed through purely aboitic reactions. The most common means for this occurs when rock containing them is formed, due to the transfer of electrons from any organic matter (which is not necessarily living organisms) trapped in the rock to ferric iron and sulphate. But this process requires very high temperatures in order to occur – and given the age of “Cheyava Falls”, the required temperatures were unlikely to have played a role in its formation. However, the presence of living microbes in the rock could result in the spots and the phosphate and sulphide minerals found within them.

Given this, the research team focused on trying to find non-biological interactions which might produce the minerals in question – and they were unable to do so.

The combination of these minerals, which appear to have formed by electron-transfer reactions between the sediment and organic matter, is a potential fingerprint for microbial life, which would use these reactions to produce energy for growth.

– NASA statement of the mineral composition found within samples of the “Cheyava Falls” rock

So, does this mean evidence of ancient microbes having once existed on Mars? Well – not necessarily; nor do the research team suggest it is. As they note in their paper, while no entirely satisfying non-biological explanation accounts for the full suite of observations made by Perseverance, it doesn’t mean that there isn’t one; it’s just that while the rover’s on-board analysis capabilities are extensive, they are also limited. In this case, those limits prevent the kind of in-depth examination and analysis of the “Cheyava Falls” rock sample which might definitively determine whether or not microbial interaction or some currently unidentified inorganic process is responsible for the deposits.

The only way either of these options might be identified is for the samples to be returned to Earth so they can be subjected to in-depth investigation. But again, as noted, that’s unlikely to happen any time soon. A major flaw with the Mars 2020 mission has always been that the samples it gathers can only be returned by a separate Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. This has proven hard to put together thanks to the complexities of the mission being such that its design has cycled through several iterations and suffered spiralling costs, reaching US $11 billion by 2024 – with the timescales constantly being pushed back to the period 2035-40.

More recently, there have been more modest proposals put forward for the MSR mission, such as that from Peter Beck’s Rocket Lab, which offered a simplified approach to collecting the Perseverance samples in 2030/31 at a cost capped at US $4 billion. However, that is currently off the table as the entire idea of any MSR project is currently facing cancellation under the Trump Administration’s proposed cuts to NASA’s 2026 budget. Whether it remains so has yet to be seen.

Following the publication of the new “Cheyava Falls” study, NASA acting Administrator, Sean Duffy, has voiced a belief MSR could be carried out “better” and “faster” than current proposals – but failed to offer examples of how. Further, it’s not clear if his comment was a genuine desire to retrieve the Perseverance samples or bluster in response to China’s Tianwen 3 mission. Slated for launch in 2028, this is intended to obtain its own samples from Mars and return them to Earth by 2031.

New Study Complicates Search for Life on Enceladus

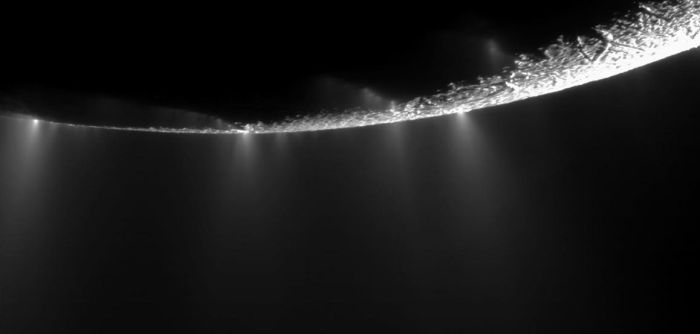

Enceladus, may be a small icy moon orbiting Saturn and just 500 km in diameter, but it has been the subject of intense speculation over the years as a potential location for life beyond Earth. Like Jupiter’s larger moon Europa, Enceladus has been imaged by space probes giving off plumes of water vapour through geysers, suggesting that under its icy surface it might have a liquid or semi-liquid ocean, warmed by tidal forces created by Saturn and its other moons.

These geysers have been shown to contain organic molecules, suggesting that the moon’s ocean might be habitable. However, new research presented during a planetary science conference hosted by Finland provides strong evidence for many of the organic molecules detected in the geysers are actually formed by interactions between radiation from Saturn’s magnetic field and the moon’s surface icy surface.

Specifically, a team based at Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics recreated conditions on the surface of Enceladus in miniature using an ice chamber and freezing samples of water, carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia – all constituents found within the ice covering Enceladus – down to -253ºC. Each sample was then bombarded with high-energy “water-group ions,” the same charged particles trapped around Saturn that constantly irradiate Enceladus, with the interaction monitored using infra-red spectroscopy.

In all five cases, the samples outgassed carbon monoxide, cyanate, and ammonium in varying amounts. These are the exactly the same core compounds as detected within the water plumes of Enceladus as detected by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in the early 2000s. Further, the five experiments all additionally produced more complex organics – carbamic acid, ammonium carbamate and potential amino acid precursors including methanol and ethanol, as well as molecules like acetylene, acetaldehyde and formamide – all of which were also detected in small quantities within the plumes escaping Enceladus, but which have never been recorded on the moon’s surface.

That all five samples produced broadly similar results in both basic and complex compounds can be taken as a strong indicator that the presence of those compounds within the Enceladus geysers could be as much due to the interaction of radiation from Saturn with the surface of the moon as much as anything organic that might be occurring in any ocean under the moon’s ice.

Although this doesn’t rule out the possibility that Enceladus’ ocean may be habitable, it does mean we need to be cautious in making that assumption just because of the composition of the plumes. [While] many of these products have not previously been detected on Enceladus’ surface, some have been detected in Enceladus’ plumes. This leads to questions about whether plume material is formed within the radiation-rich space environment or whether it originates in the subsurface ocean.

– Grace Richards, Enceladus study lead for EPSC-DPS2025.

The study also notes a further complication: the timescales necessary for radiation to drive these chemical reactions are comparable to how long ice remains exposed on Enceladus’ surface or in its plumes. This further blurs any ability to differentiate between any actual ocean-sourced organics with Enceladus’ plumes (if present) from those produced by the demonstrated surface-born interactions.

As with the “Cheyava Falls” rock samples, potentially the only way of really determining whether or not some of the organics in the geysers on Enceladus have a sub-surface / oceanic source is to go and collect samples. Again, this is not going to happen any time soon.

Currently, NASA has no current plans for a robotic surface mission to Enceladus; while the European Space Agency has outlined a complex mission to explore several of Saturn’s moons – Titan, Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus and Mimas, and which will release a lander vehicle to the south polar region of Enceladus in order to study the geysers and collect samples for in-situ analysis. However, if approved, this mission will not take place until the 2050s. The same goes for a three-part mission outlined by China’s Deep Space Exploration Laboratory (DSEL) to specifically map the surface of Enceladus and use a lander / robot drilling system in an attempt to drill down 5 km through the moon’s ice and directly sample the moon’s ocean at the ice-ocean boundary and seek out potential biosignatures. As such, any answers on the potential habitability (or otherwise) of any potential ocean within Enceladus are going to be a long time coming.

Wonderful post

LikeLike