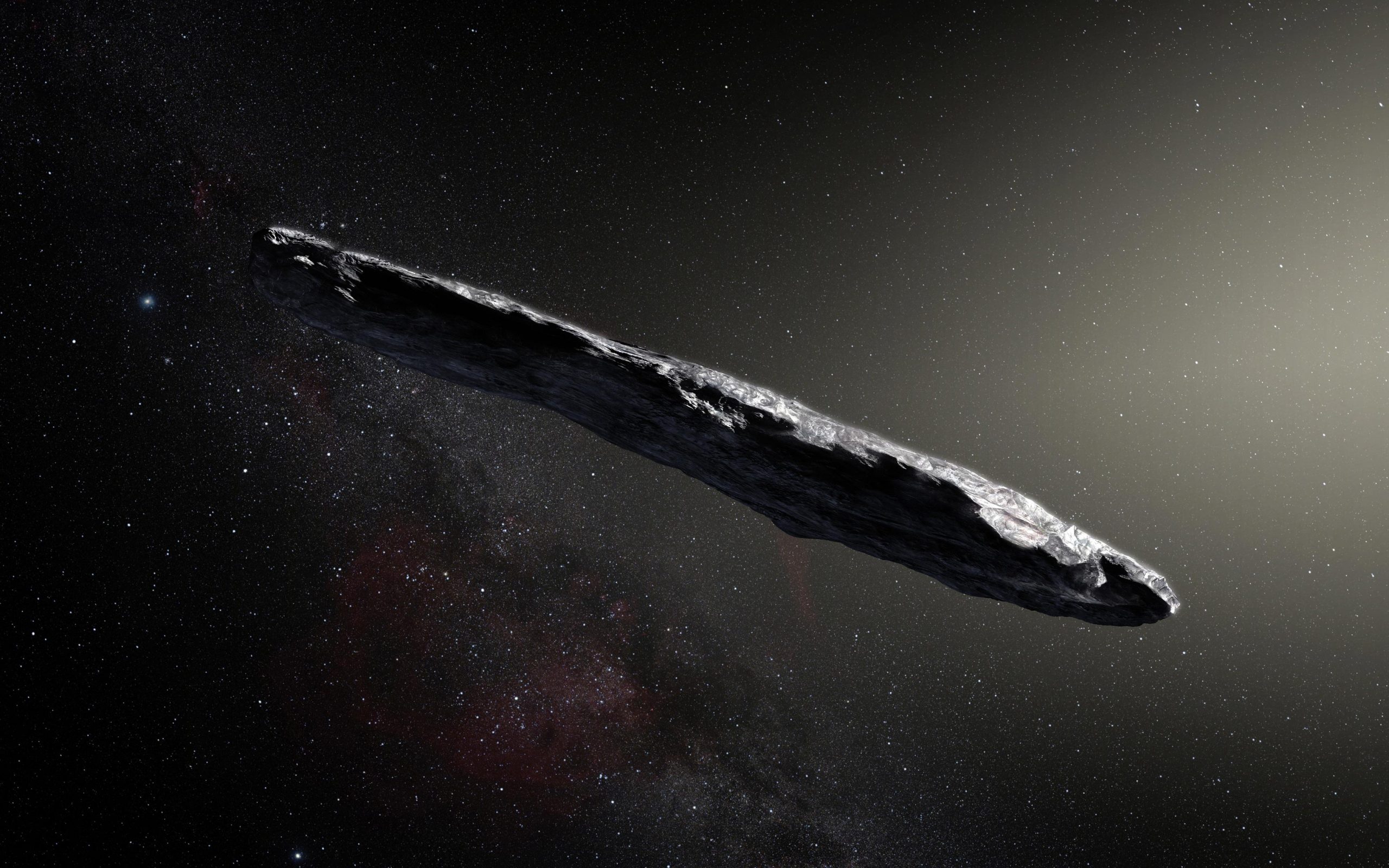

Well, that didn’t take long. A couple of weeks back I reported on 3I/ATLAS, the latest interstellar wanderer to be located passing through the solar system after 1I/ʻOumuamua (discovered in October 2017) and 2I/Borisov (discovered in August 2019), and as with both of those events, theories are surfacing that 3I/ATLAS is actually alien technology.

Most of this speculation around is easy to ignore as it has bubbled up within the morass of conspiracy theories and bots-gone-wild vacuum once called “Twitter”. These “ideas” include notions that the alien intelligences behind these “probes” are actually trying to study / bombard Mars, simply because two out of the three objects (2I/Borisov and 3I/ATLAS) happen to (have) pass(ed) somewhat close to Mars). There’s also the claim that the object “must” be of alien origin because it “comes unusually close to Venus, Mars and Jupiter”.

Similarly, the idea that it is a comet fragment has been pooh-poohed by the conspiracy theorists on the grounds “it has no tail” – despite the fact that the even in the blurred images thus far captured of the object indicate it is surrounded by a cloud of outgassed material, albeit it one without major volatiles – as yet.

However, the reason most of the claims are now being made about 3I/ATLAS relate to a paper co-authored by “noted Harvard astronomer” Avi Loeb, and which appeared on the (non-peer reviewed) preprint server arXiv. In it, Loeb and his co-authors claim – without substantive evidence – that it could be alien tech on a potentially hostile mission to spy on Earth.

This is not the first time Loeb has made such claims: he did pretty much the same when 1I/ʻOumuamua passed through the solar system. He also led a 2023 expedition to the Pacific Ocean that claimed to have recovered pieces of possible alien technology left by an unconfirmed “interstellar meteorite” – claims which have been largely debunked since.

One of the biggest issues with this theory – outside of the fact that Loeb and his colleagues offer no substantive evidence for their claims other than speculation worthy of science fiction – is that if 3I/ATLAS is intended to spy on Earth, it’s doing so in an odd way: at perihelion, for example, Earth is pretty much on the opposite side of the Sun to the object, meaning that while it will be brightly lit, that same sunlight will practically blind any instruments on the object from making meaningful optical observations of Earth across the majority of the light spectrum when 3I/ATLAS is at its closest to Earth.

In a blog post following the appearance of the paper on arXiv, Loeb’s responded to this critique by proposing that passing on the opposite side of the Sun relative to Earth is intentional on the part of the “probe’s” builders, as it allows them to deposit “gadgets” around Venus, Mars and Jupiter “unseen” from Earth, and these gadgets could then make their way to Earth undetected, and carry out their planned missions.

Most of the scientific community has responded to these claims in an appropriate manner: with a loud collective raspberry; a response which has caused to Loeb, again in his blog post to concede that, “By far, the most likely outcome will be that 3I/ATLAS is a completely natural interstellar object, probably a comet”, thereby largely deflating the “theories” put forward in his own paper.

Astronomers all around the world have been thrilled at the arrival of 3I/ATLAS, collaborating to use advanced telescopes to learn about this visitor. Any suggestion that it’s artificial is nonsense on stilts, and is an insult to the exciting work going on to understand this object.

– Chris Lintott, Professor of Astrophysics, University of Oxford,

co-researcher into the origins of 3I/ATLAS

Smithsonian Pushes Back Against Proposed Shuttle Move

The so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) from the Trump administration contains hundreds of provisions, many of which might best be described as controversial and damaging – such as causing 10.9 million middle Americans to lose health insurance coverage, increasing the US budget deficit by US $2.8 trillion and further exacerbate inequality among the American population by creating the largest upward transfer of wealth to the rich in US history.

Given all this, it seems trivial that the OBBBA is stirring up a potential fight between the Smithsonian Institution on one side, and Congress and the White House on the other. But that’s precisely what is now unfolding.

At the heart of the issue is the space shuttle Discovery, OV-103. The third of NASA’s former fleet of shuttles, Discovery is perhaps the most famous, having flown 39 times in a career spanning more than 27 years and aggregating more spaceflights than any other spacecraft as of the end of 2024.

Following the Columbia tragedy of February 1st, 2003, the decision was made to retire the three remaining operational orbiter vehicles – Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour – in 2011 and offer them up to institutions interested in displaying them as a part of America’s heritage. As a part of the arrangement it was agreed that those institutions awarded one of the vehicles would house their vehicle in a suitable climate-controlled indoor display space built at their own expense, and meet the US $28.8 million cost of decontaminating one of the vehicles and preparing it for both transportation to, and display within, said space.

In March 2011, NASA announced the Smithsonian Institute had been selected to receive Discovery, which would be displayed at its Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Centre alongside Washington’s Dulles International Airport. Later that year NASA confirmed that Atlantis would remain with NASA and and installed within a purpose-built facility at the Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex, whilst Endeavour would be transferred to the California Science Centre in Los Angeles.

During the entire competition, NASA’s Johnson Space Centre (JSC), Houston, Texas, demonstrated little interest in obtaining any of the vehicles, and nor did any major museum institution within Texas. Now, Texas senators Ted Cruz and John Cornyn want to change that in what they see as a vote-gaining (for Cornyn) and populist move to wrest Discovery from the Smithsonian and plonk it down at the Space Centre Houston Museum adjacent to the Johnson Space Centre.

The two launched their effort in April 2025 with their wildly misnamed Bring the Space Shuttle Home Act in April 2025 (if anywhere is “home” for a shuttle orbiter, it is either Kennedy Space Centre – which, as noted, already has Atlantis – or possibly Palmdale, just north of Los Angeles, California where the orbiters were built – and again, Los Angeles has the Endeavour). So popular was the bill in the Senate that it practically vanished without a trace, until the Trump administration kindly folded it into a provision within the OBBBA for reasons unknown.

Under the OBBBA provision, US $85 million is set aside for the transfer of a “space vehicle” to Texas, with Acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy ordered to nominate which vehicle no later that August 4th, 2025, with the transfer to be completed by January 2027. Whilst Discovery is not specifically named in the provision, there is little doubt at the Smithsonian or elsewhere that it is the “space vehicle” in question.

For its part, the management at the Smithsonian Institute noted that under the agreements to display the orbiter vehicles, NASA ceded all rights, title, interests and ownership for the vehicles to the institutions responsible for their future care. Ergo, they state, Sean Duffy has no legal mandate to arbitrarily reclaim and transfer any of the vehicles – a position supported by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), a nonpartisan arm of the U.S. Library of Congress. And while the Smithsonian is partially funded via Congressional appropriations, it sits as distinct from all federal agencies, allowing it to operate independently and without congressional intervention, a long-standing legal precedent having established that artefacts donated to the Institution are not federal property, even if they were originally government funded.

However, legal precedent has been shown to mean little to the Trump Administration. Nor does the Smithsonian’s management have a final say in matters. That resides with the 17-strong Board of Regents. This comprises the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (John Roberts), the Vice President of the United States, and three political appointments from the Senate and the House, and nine so-called citizen regents (appointed by the President). Given the political weight within the Board of Regents leans towards the Republican side of things (five to three), the nine citizen regents are seen as having the final say in whether or not the Smithsonian accedes to any demand to give up Discovery for relocation, or is willing to go to court over the matter.

At the time of writing, it was unknown as to which way the Board will go. However, there are some significant challenges facing any potential move of the orbiter, some of which could put it at risk of sever damage or require extensive (and potentially costly) logistics.

First is the problem of actually physically moving Discovery from Washington to Houston. During their service life, shuttle orbiters were moved across large distances using a pair of heavily modified 747 airliners called Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA). However, both of these aircraft were retired in 2012. The first, N905NA is no longer flightworthy, and has spent 13 years as part of a static display with the orbiter mock-up Independence on its back, outside the Visitor Centre at JSC. The second, N911NA, a 747-100SR, was initially transferred to NASA’s Dryden Flight Centre, where it provided spare parts for NASA’s airborne Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), with the shell of the aircraft later given on long-term loan to the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark in Palmdale, California.

Thus, in order to move Discovery by air, one of these aircraft would have to be fully refurbished, flight-tested and re-certified – which is not going to be a short-term or low-cost undertaking. As an alternative, it has been suggested that Discovery could be transferred by sea.

However, this introduces multiple issues. Even the coastal waters of the North Atlantic are hardly noted for the gentleness of their weather, so Discovery would require the use of a special barge with a suitable (and purpose-built) structure to protect the orbiter from the elements. No suitable commercial barge currently exists within US, and while the US military does have one barge that is large enough, it would require extensive modifications in order to carry Discovery safely. The CRS estimates that the cost of this could amount to some US $50 million.

On top of this are the uses of getting Discovery from Dulles International Airport to a suitable barge embarkation point, and again from the debarkation point in Texas to JSC. This would have to be done by road – and is no trivial matter. When Endeavour was moved just 19 kilometres by road from Los Angeles International Airport to the California Science Centre in 2012, the move took over a year to plan and six days to execute at a cost of US $14 million in today’s terms.

By contrast, moving Discovery from Dulles to a suitable barge embarkation point would require a road journey of between 48 and 160 kilometres, depending on which embarkation point would prove the most feasible for the use of said barge, potentially adding between US $30 to $110 million to the transport costs. Assuming the barge could be brought to the Baywater Container Terminal, Houston, and Discovery safely off-loaded there, a further road journey of some 14 km would then be required to get it to JSC.

Finally, none of this includes the cost of actually constructing a suitable building in which to display Discovery, which CRS estimates is liable to cost the US taxpayer at least US $325 million. All of which adds up to spending a lot to essentially appease a couple of political egos by an administration that is allegedly trying to reduce government fiscal expenditure; particularly when Discovery already has a more than adequate home.