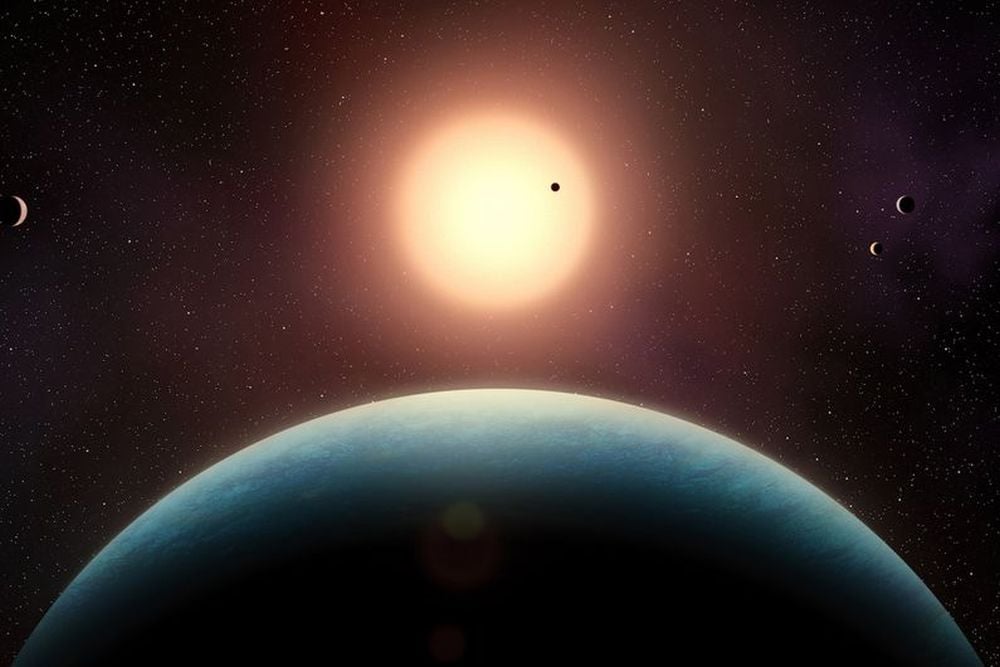

Multi-planet star systems are of considerable interest to astronomers, as they offer opportunities for comparative study which might answer questions about the formation and development of solar systems like our own. They can also help astronomers better understand star system architectures in general, help us gain more understanding of the nature of other planetary systems and the potential for life elsewhere in the galaxy, and so on.

This is why the discovery of the seven planet TRAPPIST-1 system caused such interest in 2016 onwards (see here for more), together with the Kepler-90 system (see: Space update special: the 8-exoplanet system and AI). Now there is confirmation of a further candidate for intriguing study, the rather boringly-called L 98-59.

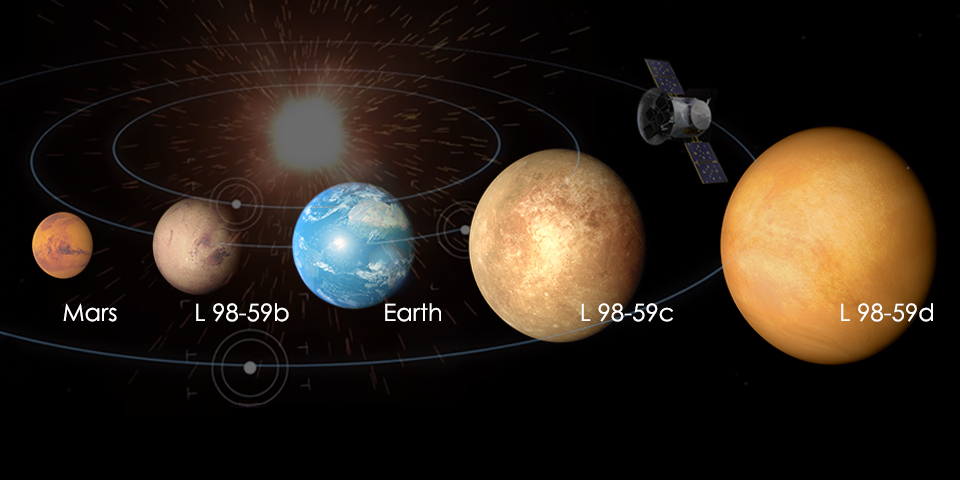

Located in the southern hemisphere sky, within the constellation of Volans, L 98-59 is some 34.6 light-years from our Sun. An M3 red dwarf star with around 0.3 solar masses, it measures approximately 0.31 solar radii. This week it was confirmed as being the home to a family of at least five planets. Three of these – L 98-59 b, c, and d were located by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS); then in 2021 a fourth non-transiting planet (i.e. one orbiting a star but which does not cross directly between the star and our solar system was located, with hints of a second potentially orbiting the star.

The fourth planet, labelled L 98-59 e was confirmed using the transit timings method and the ESO ESPRESSO system, with the fifth planet –L 98-59 f was finally confirmed this year, using the ESO HARPS system and the radical velocity method – which also suggested a sixth planet might be lurking in the system.

Given the size of their parent star, all of the planets occupy orbits very close to it. L 98-59 b orbits its parent every 2.25 terrestrial days and has an Earth-like density; but is only about 84% Earth’s mass and half its size. L 98-59 c is slightly larger than Earth, its radius being around 1.3 that of Earth, with approximately twice the mass; it orbits its star every 3.7 terrestrial days. The fourth planet, L 98-59 e is roughly the same size as L 98-59 c, but with 2.8 Earth masses and takes 12.8 terrestrial days to complete an orbit. All three of these worlds suggest they are rocky and potentially volcanic in nature, although they do not appear to have significant atmospheres.

Sitting between L 98-59 c and e, and orbiting its parent every 7.4 days, is L98-59 d, which is believed to be a hycean (water) world with around 30% of its total mass made up of water. Reports on its atmosphere vary, and it is around 1.6 Earth radii in size and has 1.6 Earth masses. The newly-confirmed planet, L 98-59 f, is in the optimistic habitable zone of the star. It has a minimum mass of about 2.80 Earth masses, about 1.4 Earth radii, and follows a 28 day orbit.

One of the most interesting things about this system is that all the planets follow near circular orbits. This means they’re amenable to atmospheric spectroscopic studies by the JWST or other telescopes. Their comparative sizes also offer an opportunity to answer some key question, such as: what are super-Earths and sub-Neptunes made of? Do planets form differently around small stars? Can rocky planets around red dwarfs retain atmospheres over time? The fact that there appears to be both a hycean world and a world located within the star’s nominal habitable zone presents opportunities for studying potentially habitable worlds orbiting low-mass stars.

This latter aspect is of significance, as habitable environments within planets orbits low-mass stars like L 98-59 (and indeed, those around the likes of TRAPPIST-1) is highly contentious. Firstly, while they are long-lived and can enter into a stable maturity, red dwarf stars can also be subject to massive solar flares which, given how closely their planets orbit them, could easily rip away atmospheres make it that much harder for life to gain a toe-hold.

Additionally, because of their close proximity to their parent star, these planets are liable to be tidally locked, always keeping the same side pointing towards the star. This could play havoc with any atmosphere such a planet might have, the star super-heating the side facing it whilst the planet’s far side remains frigid and dark, potentially limited any habitable zone on the planet to the pole-to-pole terminator between the two sides of the world.

Joining a select group of relatively nearby planetary systems, L 98-59 is to become the focus of some intense study through the likes of the James Webb Space Telescope.

Skyfall: Dropping Helicopters on Mars?

Building on the success of the Ingenuity helicopter delivered to Mars as a part of NASA’s Mars 2020 exploration programme (and covered extensively in these pages), Skyfall is a new mission concept being proposed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and their principal partner with Ingenuity, AeroVironment.

Were it to develop into a mission, Skyfall would see a total of six Ingenuity-class helicopter drones delivered to Mars and deployed in a manner indirectly drawing on the Skycrane system used to deliver the Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity and the Mars 2020 rover Perseverance to the surface of Mars.

Skyfall would see the six helicopters carried to Mars within a protective aeroshell and heat shield. Once within the Martian atmosphere and descending under a parachute, the heat shield will be jettisoned and a “launch tower” extended below the aeroshell, allowing the helicopters to start their motors and fly clear of the aeroshell to start six individual but parallel missions.

By releasing the helicopters in the air, the mission avoids the need for a complex landing and deployment system, in theory reducing both mission complexity and cost – although there are obvious challenges involved in making aerial launches from under a descending platform.

The six drones would be enhanced versions of Ingenuity, charged with a variety of tasks including recording and transmitting high-resolution surface images back to Earth, using ground-penetrating radar to investigating what lies under the surface they overfly – such as potential pockets of water ice that could greatly assist future surface operations -, and identifying possible landing sites for future human missions to the Red Planet.

Like Ingenuity, the six drones would be capable of landing in order to use solar arrays to recharge their battery systems. However, exactly how far each vehicle will be able to fly between landings has not been defined, nor has their total mass, or the portion of that mass given over to science instruments and battery packs. If the concept progresses, these details will doubtless be defined and made public. As it is, AeroVironment has begun internal investments and coordination with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to facilitate a potential 2028 launch of Skyfall.

NASA to Lose 3,900 Personnel and Gains a new Acting Administrator

For the last couple of weeks, rumours have been circulating that a large number of NASA personnel has applied to take the Trump administration’s “deferred resignation” offer, by which staff can go on paid administrative leave until such time as an actual departure date can be agreed.

The numbers had been put at somewhere between 3,500 and 4,000 personnel – many from senior management and leadership roles. Some of the rumours had been played down by the current temporary NASA senior administrator, but on July 25th, the date the offer of “deferred resignation” closed, NASA News Chief Cheryl Warner confirmed a total of around 3,900 personnel – 20% of the total workforce – have, or will be departing.

The figure might yet be subject to adjustment (up or down) as a post-offer analysis is carried out to ensure that those applying for deferred resignation do not impact the agency’s focus on safety and the Trump-demanded focus on sending humans to the Moon and Mars.

At the same time as the rumours of the workforce cuts started circulating earlier in July, the Trump Administration further caught NASA off-guard by announcing that secretary of transportation Sean Duffy will be taking over as interim NASA Administrator until a permanent appointment can be made. The announcement came just days after Trump abruptly withdrew nominee Jared Isaacman from the running just ahead of his expected confirmation, allegedly as a result of Trump’s public spat with Elon Musk.

No-one at NASA headquarters was informed of the decision ahead of Trump’s social media announcement. It had been expected that existing acting administrator, Janet Petro, would remain in place until a suitable nominee was put forward in Isaacman’s stead. Whilst not a part of the Trump administration, Petro has tended to move in the direction the administration wants with regards to NASA – such as encouraging workforce reduction through early retirements, etc., – and had been regarded within the agency as a safe pair of hands.

A television presenter turned prosecutor turned politician, Duffy is primarily known as a vocal supporter of Donald Trump and his various policies, notably in the areas of decrying climate change, and diversity and equality in employment.

Some have attempted to paint his appointment positively, stating he could bring NASA the kind of direct access to the White House Petro lacks. However, others seen his appointment as a means of forcing through changes at NASA that are in line with Trump’s goals of reducing spending on science and R&D, and focusing only on human missions to the Moon and Mars.

Spain to the Rescue?

The Thirty Metre Telescope (TMT) has been in development since the early 2000s – and if it ever gets built, it will be the second largest optical / infrared telescope in the world, with an effective primary mirror diameter of 30 metres. Only the European-led Extremely Large Telescope – ELT – will be larger, with a primary mirror effectively 39 metres across.

Primarily a US-led project but with strong international involvement from Europe, Canada, Japan, India and even China, the TMT has been beset by problems. Most notably, these have involved protests over the proposed location for the observatory – on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, within the area designated the Mauna Kea Observatories Grounds, and home to 13 other astronomical facilities. However, Mauna Kea is also a sacred site and largely conservation land, and the telescope, coupled with all the environmental impact that it would bring, was seen as a step too far by many, and a battle has been waged back and forth for some 16 years, preventing any construction from proceeding.

In 2019, a proposal was made to have the TMT built in Las Palma in the Canary Islands. This was initially approved by the Spanish authorities, but has also been subject to objections. Some of these again relate to the environmental impact of such a massive construction project, but there are also astronomical objections as well; in particular, La Palma does not have the same elevation as Mauna Kea, meaning that high atmosphere water vapour could limit much of the telescope’s infrared operations (water vapour tends to absorb light in the mid-infrared spectrum).

Most recently, TMT has been under threat due to the Trump Administration’s cuts to the National Science Foundation’s budget (the NSF having the remit of oversee the construction and operation of the TMT), with the telescope directly singled-out for cancellation – and this despite the fact that China and India have agreed to meet the lion’s share of the estimated US $1 billion construction cost, and Canada offering to contribute US $24.3 million a year over ten years for the telescope’s operation.

Now the government of Spain has stepped in, offering to commit US $471 million (400 million Euros) towards the telescope’s operating costs – if the US agrees to have the facility located on La Palma. It’s not clear how the US will respond to the offer – or what can be done over the possible limitations of TMT’s infrared mission. However, TMT is also seen as critical to providing very large optical telescope coverage of the whole sky, with the TMT covering northern skies and the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), based in Chile to cover the southern skies, with the two intended to work in collaboration and with Europe’s ELT (also in the southern hemisphere).

GMT has a significant advantage over TMT in that its location is not controversial, allowing construction to go ahead to a point where the National Science Foundation has given the Trump administration a guarantee the project can be completed to reach operational status without the need for additional funding in 2026. Thus there have been no calls for its cancellation.