China is continuing to expand its space endeavours on both the public and private fronts – drawing some flak from SpaceX fans in the process.

On Wednesday, May 28th, a Long March 3B rocket lifted-off from the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre, southwest China at 17:31 UTC, carrying aloft the Tianwen-2 explorer, bound for 469219 Kamoʻoalewa (2016 HO3), an Apollo class, near-Earth object (NEO) and quasi-satellite of this planet.

A sample-return mission, Tianwen-2 is due to rendezvous with the 40-100 metre diameter asteroid in July 2026. It will spend some 7 months examining it and attempt to collect samples from its surface and sub-surface, using both touch-and-go (dropping briefly onto the asteroid in an attempt to gather samples before being pushed away using spring tension in the sample arm), and anchor-and-attach (literally hooking itself onto the asteroid). Departing the asteroid in April 2027, Tianwen-2 will then swing by Earth, dropping off gathered samples in a re-entry capsule in November of that year. In all, it is hoped that around 100 grams of material will be gathered from the surface and sub-surface environments of the asteroid. An interesting aspect of the mission is that Tianwen-2 will attempt to deploy a nano-rover onto the surface of 469219 Kamoʻoalewa, and place a nano-satellite in orbit around it.

The aim of the mission is to gain insight into 469219 Kamoʻoalewa, and either answer questions as to whether or not it is actually a chunk of the Moon blasted clear following an asteroid impact or, if not, it is hoped the mission will provide insight into the nature and characteristics of NEOs (particularly whether they also contain organic molecules), and allow comparative studies between the samples returns and those from Hayabush2 and OSIRIS-REx, furthering our understanding of asteroids and the role in the early solar system.

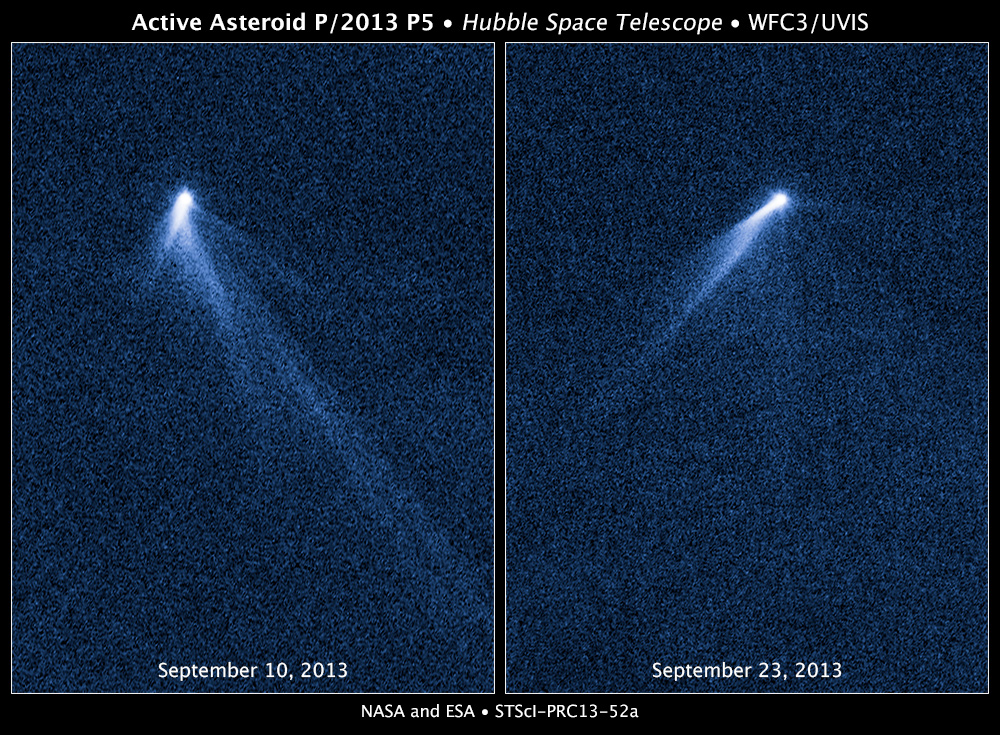

Returning the samples to earth will not be the end of Tianwen-2’s mission. Using Earth’s gravity after releasing the sample return capsule the vehicle to push itself onto a rendezvous 311P /PANSTARRS (aka P/2013 P5), which it will reach in 2031. This is an unusual object called an active asteroid – an object with an asteroid-like orbit, but exhibiting comet-like visual characteristics (such as having a tail). Estimated to be 240 metres across and with a sidereal period of 3.24 years, it was first located in 2013, and attracted attention due to its fuzzy, smudged appearance in initial images. Later that year, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed that the fuzziness was due to it having around 6 individual tails. These are thought to be the result of the asteroid is either spinning so fast, lose surface material is being thrown off of it, or that a series of “impulsive dust-ejection events” of unknown origin gave rise to a cloud of debris around the asteroid, which were then formed into the tails by solar radiation pressure.

Rather than just making a fly-by of 311P /PANSTARRS, the plan is for Tianwen-2 to use its solar-eclectic propulsion system to decelerate as it approaches the asteroid so that it can enter orbit and study it at length.

Also on May 28th, the private-venture launch company, Space Epoch, became the first Chinese company to make a sea-based vertical launch of a reusable rocket element and successfully recover it in a controlled splash-down.

The Yuanxingzhe-1 (YXZ-1 – also referred to a “Hiker 1”) is designed to be a reusable booster some 64 metres tall and capable for delivering 6.5 tonnes to a Sun-synchronous orbit (SSO). For the May 28th, flight, a test article standing 26.8 metres tall and using a single Longyun methane-liquid oxygen (methlox) motor and massing 57 tonnes, lifted-off from the sea-based Haiyang spaceport, Shandong province, at 20:40 UTC, climbing to an altitude of 2.5 km. The motor brought the vehicle to a hover before shutting down, allowing the vehicle to fall back towards the sea using four grid fins to maintain its vertical orientation. After a free descent, the motor then re-lit, slowing the vehicle and bringing it to a safe hover just a metre or so above the water. It then shut down, allowing the vehicle to gently enter the water and topple onto its side and await recovery. In all, the 125-second flight verified the broad operational parameters of the full-size Hiker-1, which will also splash-down at the end of its flights, rather than trying to land or be caught out of the air.

The flight, defined by Space Epoch as “100% successful”, immediately came under attack by SpaceX fans. The latter claimed China was merely “copying” SpaceX rather than innovating, particularly through the use of stainless steel in vehicle construction and methlox propellants, together the the use of four grid fins on the rocket for steerage / stability – as if SpaceX had any sole claim to these capabilities (they have not even patented the use of grid fins for rocket attitude control in an atmosphere).

A similar “they’re just copying!” came on May 29th, when another Chinese start-up, Astronstone, announced it has received sufficient initial funding to push ahead with its design for a reusable launch vehicle. Called the AS-1, this is intended to deliver up to 10 tonnes to low-Earth orbit (LEO) when being reused and up to 15.7 tonnes in fully expendable mode. It is to utilise methlox propulsion, stainless steel construction, grid fins for descent control and is to be designed to boost-back to its launch facilities and captured by “chopsticks” mounted on the launch tower.

In this, Astronstone is not shy about taking a leaf from the SpaceX book; the only difference is that of scale: AS-1 will be a modest 70 metres tall with a 4.2 metres main diameter (roughly the height of SpaceX Super Heavy, with half the diameter), while its 10-tonne reusable payload lift capacity is well in keeping with most modern commercial launch requirements. If successful, the company plan on offering the AS-2, capable of around two or three times the payload capacity of AS-1.

NASA: Budget Fears Confirmed; Administrator Nominee Removed

Earlier in May 2025, I covered the threats to NASA’s budget under cuts being considered by the Trump administration (see: Space Sunday: of budgets and proposed cuts and Space Sunday: more NASA budgets threats). At the time, the concerns were based on a so-called “skinny” budget document released by the administration, which outlined where the cuts would fall.

On May 31st, 2025, the administration quietly published a more detailed version of its federal budget proposal. This solidifies many of the threats to NASA’s mission. It confirms the intent to slash NASA’s budget by 24%, with the majority of the cuts coming within NASA’s space science, Earth sciences, aeronautic and education areas. In real terms, and adjusted for inflation, it sees the agency’s budget reduced to levels not seen since 1961, with the potential for 5,500 job losses and possible centre closures.

The science budget zeros-out 41 in-development or in-progress science missions. These Include:

- Many NASA Earth science programmes and missions, current and future, including the decadal survey Earth System Observatory missions; cancellation of most venture-class Earth science missions; and potentially impacts to the “cyclone watching” CGNSS network currently in operation.

- The in-development DAVINCI and VERITAS missions to Venus, and the Mars Sample Return Mission (MSR – not helped by NASA repeatedly shooting itself in the foot where this is concerned).

- The operational Mars Odyssey and MAVEN Mars orbiters (ending two valuable missions and limiting relay communications with other Mars missions); the New Horizons mission; OSIRIS-APEX – a mission extension to the highly-successful OSIRIS-REx, and intended to provide information on the Earth orbit crossing asteroid (and potential future impactor) 99942 Apophis.

- Multiple astrophysics programmes and missions, including the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and multiple, low-cost but highly effective Explorer-class missions.

The budget additional calls for an effective crippling of NASA’s biological and physical sciences, reducing its budget to just US $25 million from US $87 million, and ending cooperation with the European Space Agency on Venus and Mars missions. While the flagship Nancy Grace Roman Telescope survives cancellation, it receives just half its requested budget – US $156.6million – potentially impacting its ability to be launched in 2026.

In terms of human spaceflight, the Trump administration is apparently initiating a “bold mission of planting the American flag on Mars”, which sees some 6.38% of NASA’s total budget being steered into Mars-centric initiatives:

- US $864 million for a “Commercial Moon to Mars (M2M) Infrastructure and Transportation Program” (which as side-note, will replace SLS / Orion after Artemis 3 – assuming any such system is actually flying by then).

- A total of US $400 million to be put into a “near-term entry, descent, and landing demonstration for a human-class Mars lander”, and commercial payload deliveries to Mars.

Some of this will be offset by the cancellation of the Lunar Gateway boondoggle; however, it is hard not to see hints of the influence of the SpaceX CEO in these matters. He has been vocal in his opposition to anything other than his “grand vision” of colonising Mars, and these budget allocations, particularly the US $400 million appear to be directly tailored to SpaceX’s benefit, the company apparently prioritising landing a “human-class lander” as soon as possible, and then moving directly to cargo deliveries.

Isaacman Out

The budget details came alongside the shock announcement that the White House has withdrawn entrepreneur Jared Isaacman at its nominee to lead NASA.

Isaacman’s nomination caused mixed reactions when first announced. Whilst the majority were positive, there were also concerns over his ties to the SpaceX CEO, and the latter’s views on NASA’s future direction. During his Senate confirmation hearings, Isaacman handled the latter concerns directly, and indicated his own opposition to some of the proposals in the Trump NASA 2026 budget. As such, it was widely anticipated the Senate would confirm his appointment on June 3rd, 2025.

No reason has been given by the White House for withdrawing his nomination. Some have speculated it is as a result of the recent rift between the President and the SpaceX CEO, with whom Isaacman has a strong association. Also, Isaacman’s confirmation hearing also revealed he has been a past financial supporter of the Democratic Party – something hardly likely to endear him to the White House incumbent. In a statement on the withdrawal, White House assistant press secretary Liz Houston would only say:

The Administrator of NASA will help lead humanity into space and execute President Trump’s bold mission of planting the American flag on the planet Mars. It’s essential that the next leader of NASA is in complete alignment with President Trump’s America First agenda and a replacement will be announced directly by President Trump soon.

Again, the emphasis on Mars here is loud enough to be almost deafening – and in line with the goals of the SpaceX CEO. This is not to say the the latter will now be the likely pick to head-up NASA; it is highly unlikely he would survive Senate hearings even if nominated. However, it does perhaps indicate his push for having NASA effectively abandon the International Space Station and the Artemis programme in favour of Mars have been taken to heart by a President who is all about being “first” in everything.

Thus far, all of the Trump administration proposals for NASA’s budget have been met with widespread condemnation from the aerospace, science and educations sectors in the US. Many are hoping that Congress will stop this tear-down of NASA dead in its tracks when the budget comes before the Capitol later in the year. As to Isaacman being removed as nominee, this has been received with dismay and upset within the US space industry, and leaves NASA in a continuing state of limbo.

Starship IFT9: Up and Bang Again1

On Tuesday May 27th, 2025, SpaceX once again attempted to carry out their 9th integrated flight test (IFT-9) of their Starship / Super Heavy combination in the hope of getting the former into sub-orbital space to carry out a series of tests, and use the latter as a test article during its descent back to the Gulf of Mexico. As such, the flight had a number of distinct goals for both the booster and the starship vehicle.

- Booster (√ = success; Χ = failure):

- Re-fly a Super Heavy for the first time – the unit used in the January 2025 test article flight (with just 4 of its 33 Raptor 2 motors replaced) (√).

- Attempt a new “rollover” manoeuvre after starship separation (√).

- Test a new high angle of attack re-entry into the lower atmosphere in an attempt to use atmospheric drag to reduce velocity and reduce the need to carry propellants for propulsive braking (Χ).

- Carry out an updated engine braking burn (Χ).

- Splash-down in the Gulf of Mexico (Χ).

- Starship (√ = success; Χ = failure):

- Reach a sub-orbital trajectory (√).

- Deploy a set of 8 Starlink satellite simulators, testing the payload bay slot in the process (Χ).

- Carry out the re-start of a sea-level Raptor engine to test de-orbit burn capabilities (Χ).

- Make a successful re-entry into the atmosphere and test updates made to the thermal protection system and to hopefully reduce burn-through on the fore-and-aft aerodynamic flaps (Χ).

- Splash-down in the Indian Ocean (Χ).

Lift-off was at 23:37 UTC, from the SpaceX Starbase City facilities in Texas, and proceeded to a successful staging. The booster then performed its intended roll-over and carried out a good boost-back burn. It was lost 6 minutes 20 seconds after launch, as 13 of the engines were due to fire at the start of their braking burn.

The starship vehicle continued on to its sub-orbital trajectory and successfully shut-down its motors. The deployment of the payload simulators was due at 18 minutes into the flight, but was abandoned when the deployment slot door again failed. By 30 minutes into the flight the vehicle was pitching / rolling wildly, and SpaceX confirmed they had lost all attitude control, likely the result of a propellant system leak. The vehicle subsequently made an uncontrolled re-entry over the Indian Ocean 46 minutes after launch and largely burned-up.

Whilst subject to confirmation, the propellant leak potentially hints at a vulnerability in the starship design. Most space vehicles utilise hypergolic thrusters for attitude control and fine manoeuvring. Independent of the main propulsion system, these avoid the need for complicated propellant bumps, etc.. However, the propellants are high toxic, and such systems do add mass to a vehicle. By contrast, SpaceX effectively pumps boil-off gases from the main propellant tanks around the vehicle to so-called “cold thrusters” and their own small tanks. Doing so removes the need for the majority of the mass (and engineering space) used by hypergolic thruster systems and avoids the complications of handling toxic materials during vehicle refurbishment between flights. However, the plumbing used to deliver the gases around Starship and Super Heavy is all interconnected; thus – and possibly as demonstrated with IFT-9 – there is a risk of a single leak impacting multiple attitude control thrusters.

Both the booster and the starship came down within their designated hazard zones; however, the flight will be subject to an FAA-required mishap investigation.

- With apologies to the estate of J.R.R. Tolkien and Bilbo Baggins, Esq., formerly of The Shire