As I noted back in July 2024, classifying just what “is” and “is not” a “planet” is something of a minefield, with the entire debate going back to the 1800s. However, what really ignited the modern debate was – ironically – the search for the so-called “Planet 9” (or “Planet X” as it was then known), a body believed to be somewhere between 2 and 4 times the size of Earth and around 5 times its mass (see: Space Sunday: of “planet” and planets).

That hunt lead to the discovery of numerous bodies far out in the solar system’s Kuiper Belt which share similar characteristics to Pluto (size, mass, albedo, etc), such as Eris (which has at least one moon) Makemake, Haumea (which has two moons), Sedna, Gonggong and Quaoar (surrounded by its own ring of matter), all of which, like Pluto, appear to have reach a hydrostatic equilibrium (aka “nearly round shape”).

The discovery of this tiny worlds led to an increasing risk that the more we looked into the solar system, so the number of planets would require updating, causing confusion. So, in 2006, the IAU sought to address the issue by drawing up a definition of the term “planet” which would enable all these little planet-like bodies to be acknowledged without upsetting things too much. In the process, Pluto was relegated to the status of “dwarf planet”, in keeping with the likes of Ceres in the inner solar system, Eris, Makemake et al. This make sense – but that’s not to say it didn’t cause considerable upset.

The definition was also flawed from the outset in a couple of ways. Firstly, if taken strictly, the criteria the IAU had chosen meant that Saturn Jupiter, Mars and Earth were actually not planets, because all of them have not “cleared the neighbourhood around [their] orbit[s]”: all of them have gatherings of asteroids skipping around the Sun in the same orbit (notably some 10,000 for Earth and 100,000 for Jupiter).

Secondly, that body has to be “in orbit around the Sun” pretty much rules out calling called planet-like bodies orbiting other stars “planets”; something which given all the exoplanet discoveries by Kepler and TESS et al has become something of a bite in the bum for the IAU. As a result, the “pro-Pluto is a planet” brigade have felt justified in continuing their calls for Pluto to regain its planetary status.

Several attempts have been made to try to rectify matters in a way that enables the IAU to keep dwarf planets as a recognised class of object (including Pluto) and which addresses the issues of things like exoplanets. The most recent attempt to refine the IAU’s definition took place in August 2024, at the 32nd IAU General Assembly, when a proposal offering a new set of criteria was put forward in order for a celestial body to be defined as a planet.

Unfortunately, the proposal rang headlong into yet more objections. The “Pluto is a planet” die-hards complained the new proposal was slanted against Pluto because it only considered mass, and not mass and hydrostatic equilibrium, while others got pedantic over the fact that while the proposal allowed for exoplanets, it excluded “rogue” planets – those no longer bound to their star of origin but wandering through the Galaxy on their own – from being called “planets”. Impasse ensued, and the proposal failed.

In the meantime, astronomers continue to discover distant bodies that might be classified as dwarf planets, naturally strengthening that term as a classification of star system bodies. This last week saw confirmation that another is wandering around the Sun – and a very lonely one at that.

Called 2017 OF201 (the 2017 indicating it was first spotted in that year), it sits well within the size domain specified for dwarf planets, being an estimated 500-850 metres across, and may have achieved hydrostatic equilibrium (although at this point in time that is not certain). Referred to as an Extreme Trans-Neptunian Object (ETNO, a term which can be applied to dwarf planets and asteroids ), it orbits the Sun once every 25,000 years, coming to 45 AU at perihelion before receding to 1,700 AU at aphelion (an AU – or astronomical unit – being the average distance between Earth and the Sun).

As well as strengthening the classification of dwarf planets (and keeping Pluto identified as such), 2017 OF201 potentially adds weight to the argument against “Planet 9”, the original cause for the last 20 years of arguing over Pluto’s status.

To explain. Many of ETNOs and Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) occupy very similar orbits to one another, as if they’ve somehow been clustered together. For example, Sedna has a number of other TNOs in orbits which closely match its own, leading the group as a whole to be referenced informally as “sednoids”. Among “Planet 9” proponents, this is taken as evidence for its existence, the argument being that only the influence of a large planetary body far out beyond Neptune could shepherd these ETNOs and TNOs into clusters of similar orbits.

However, by extension, this also means that 2017 OF201 – together with 2013 SY99 and 2019-EU5 should have also fallen to the same influence – but none of them have, orbiting the Sun quite independently of any clusters. This potentially suggests that rather than any mysterious planet hiding way out in the solar system and causing the clustering of groups of TNO orbits, such grouping are the result of the passing influence of Neptune’s gravity well, together with the ever-present galactic tide.

Thus, the news concerning 2017 OF201 confirmation as a Sun-orbiting, dwarf planet-sized ETNO both ups the ante for Pluto remaining a dwarf planet and simultaneously potentially negating the existence of “Planet 9”.

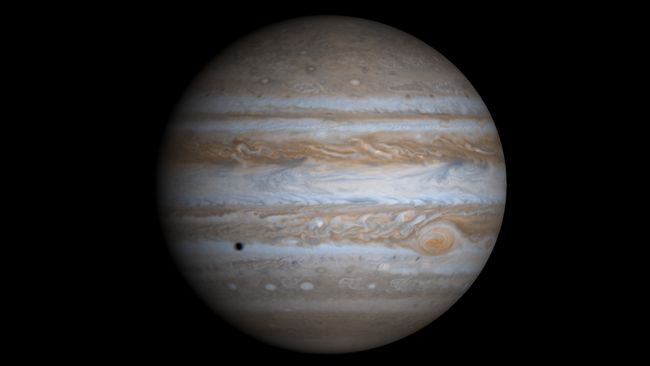

Jupiter: Only Half the Size it Once Was?

Definitions and classifications aside, Jupiter is undoubtedly the planetary king of the solar system. It has a mass more than 2.5 times the total mass of all the other planetary bodies in the solar system (but is still only one-thousandth the mass of the Sun!) and has a volume 1,321 times that of Earth. It is also believed to have been the first planet to form in the solar system; possibly as little as one million years after the Sun itself was born, with Saturn following it shortly thereafter.

Jupiter is an important planet not just because of its dominance and age, but because of the role it and Saturn played in the overall formation of the solar system, although much of this is subject to contention. The primary concept of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s voyage through the solar is referenced as the “grand tack hypothesis“, on account of the two giants migrating through the solar system in the first few millions of years after they form.

Under this theory, Jupiter formed around 3.5 AU from the Sun, rapidly accreting a solid core and gaining mass to a point where it reach around 20 times Earth’s mass (although Earth would not form for another 45-50 million years). At this point, it’s mass and size (and those of Saturn) were such that they entered into a complex series of interactions with one another and the Sun, with both migrating towards the Sun, likely destroying a number of smaller proto-planets (all of them larger than Earth) along the way. At some point, these interactions reversed, and both infant planet started migrating away from the Sun again, clearing the way for the remnants of the smaller proto-planets they’d wrecked to gradually accrete to form what we now know to be the inner planets, as Jupiter and Saturn continued outwards to what are now their present orbits.

Believed to have occurred over between 4 to 6 million years, the “grand tack hypothesis” is contentious, as noted, and there are alternate theories concerning Jupiter’s formation and the early history of the solar system. Because of this, astronomers Konstantin Batygin (who, coincidentally, is one of the proponents of the “Planet 9” theory) and Fred C. Adams used complex computer modelling to try to better understand Jupiter’s formation and early history, in order to try to better determine how it may have behaved and affected the earliest years of the solar system’s formation.

In order to do this, and not be swayed by any existing assumptions concerning Jupiter’s formation, they decided to try to model Jupiter’s size during the first few million years after its accretion started. They did this using the orbital dynamics of Jupiter’s moons – notably Amalthea and Thebe, together with Io, Jupiter’s innermost large moon – and the conservation of the planet’s angular momentum, as these are all quantities that are directly measurable.

Taken as a whole, their modelling appears to show a clear snapshot of Jupiter at the moment the surrounding solar nebula evaporated, a pivotal transition point when the building materials for planet formation disappeared and the primordial architecture of the solar system was locked in. Specifically, it reveals Jupiter grew far more rapidly and to a much larger size than we see today, being around twice its current size and with a magnetic field more than 50 times greater than it now is and a volume 2,000 times greater than present-day Earth.

Having such a precise model now potentially allows astronomers to better determine exactly what went on during those first few million years of planetary formation, and what mechanisms were at work to give us the solar system we see today. This includes those mechanisms which caused Jupiter to shrink in size to its present size (simple heat loss? heat loss and other factors?) and calm its massive magnetic field, and the time span over which these events occurred.

Yeah. Finding Life is Hard

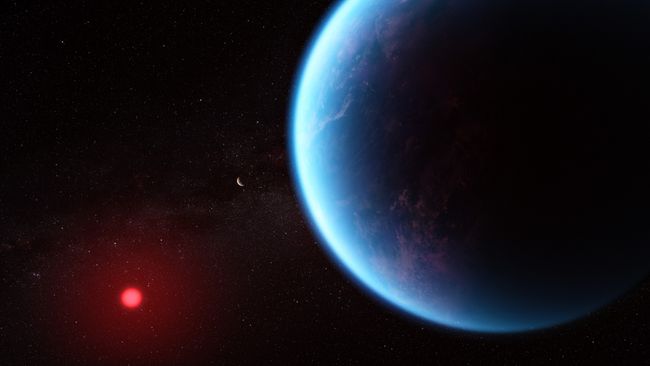

In March, I reported on a possible new means to discover evidence of biosigns on worlds orbiting other stars by looking for evidence of methyl halides in their atmospheres (see: Space Sunday: home again, a “good night”, and seeking biosigns). In that reported, I noted that astronomers had potentially found traces of another element associated with organics, dimethyl sulphide (DMS) , within the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18b, a hycean (water) world.

This is the strongest evidence yet there is possibly life out there. I can realistically say that we can confirm this signal within one to two years. The amount we estimate of this gas in the atmosphere is thousands of times higher than what we have on Earth. So, if the association with life is real, then this planet will be teeming with life.

– Prof Nikku Madhusudhan, lead investigator into the study of the atmosphere of K2-18b and the apparent discovery of dimethyl sulphide.

Now in fairness, the team behind the discovery did note that it needed wider study and confirmation. Extraordinary claims requiring extraordinary proof and all that. And this is indeed what has happened since, and the findings tend to throw cold water (if you forgive the pun) on that potentially wet world 124 light-years away, having dimethyl sulphide or its close relative, dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) in anywhere near detectable levels.

The more recent findings come from a team at the University of Chicago led by Rafael Luque and Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb. Like Madhusudhan and his team at Cambridge University, the Chicago team used data on K2-18b gathered by the James Webb Space telescope (JWST). However, in a departure from the Cambridge team, Luque and his colleagues studied the data on the planet gathered by three separate instruments: the Fine Guidance Sensor and Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (FGS-NIRISS), the Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) – the latter being the sole source of data used by the Cambridge team.

Combing the data from all three instruments helps ensure a consistent, planet-wide interpretation of K2-18b’s atmospheric spectrum, something that cannot be obtained simply by referencing the data from a single instrument. And in this case it appears that by only focusing on MIRI, the Cambridge team inferred a little too much in their study.

We reanalyzed the same JWST data used in the study published earlier this year, but in combination with other JWST observations of the same planet … We found that the stronger signal claimed in the 2025 observations is much weaker when all the data are combined. We never saw more than insignificant hints of either DMS or DMDS, and even these hints were not present in all data reductions.

Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb

Most particularly, the much broader set of spectrographic data gathered from the three instruments points to some of the results observed by Madhusudhan’s team could actually be produced entirely abiotically, without any DMS being present. The Chicago paper has yet to be peer-reviewed, but their methodology appears sufficient to roll back on any claims of organic activities taking place on K2-18b or within its atmosphere.

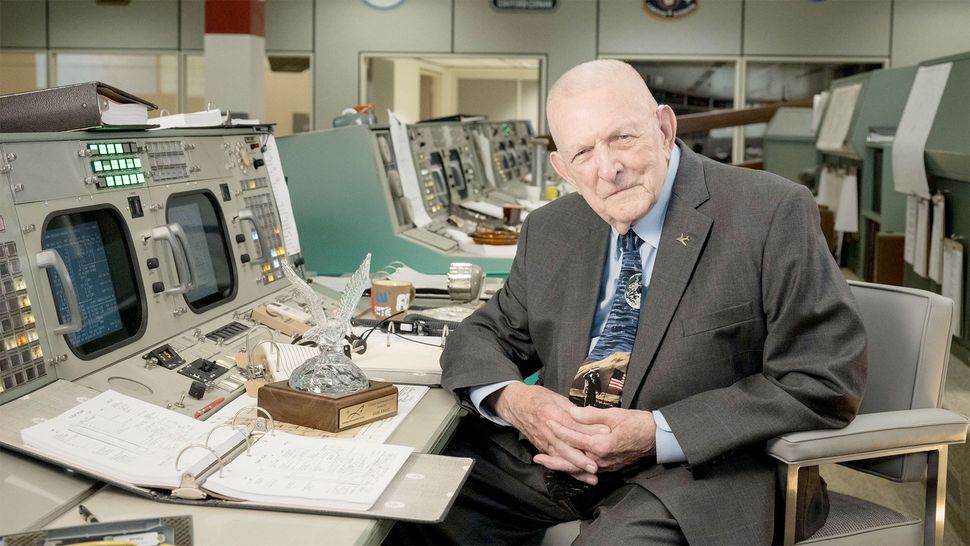

AAS Recognises Gene Kranz

Eugene Francis “Gene” Kranz is a genuine NASA legend. He may never have flown in space, but he played a crucial role – along with the late Christopher C. Kraft (also see: Space Sunday: a legend, TESS and a rocket flight), John Hodge and Glynn Lunney (also see: Space Sunday: more from Mars and recalling a NASA legend) – in formulating how NASA runs it manned / crewed spaceflights out of their Mission Operations Control Centre, Houston.

He is particularly most well-known for his leadership of his White Team during the Apollo 11 Moon landing in 1969, and for leading the work to get the crew of Apollo 13 back to Earth safely when that mission faced disaster. As a result of the latter, Kranz and his entire White Team received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1970 as well as being immortalised in film and television (although the line “Failure is not an option” was not something Kranz ever said – he instead used it as the title for his 2000 autobiography; the quote was purely fiction and used in the 1995 Ron Howard film Apollo 13, which saw Ed Harris play Kranz).

His career at NASA ran from 1960 through 1994, during which he rose from Mission Control Procedures Officer to Director of Mission Operations. As a result, he has been the recipient of NASA’s own Distinguish Service Medal, Outstanding Leadership Medal and Exceptional Service Medal.

And he has now been similarly recognised by the American Astronautical Society, which on May 21st, 2025, named him the recipient of their 2024 Lifetime Achievement Award. Only presented every 10 years, the award recognises Kranz for his “exemplary leadership and a ‘must-never-fail’ style that ensured historic mission successes, empowered human space exploration, saved lives and inspired individuals around the world.”

The ceremony took place at the Johnson Space Centre, Houston, Texas, where Kranz was also able to revisit the place where he and his teams and colleagues made so much history: the Apollo Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR – pronounced Mo-kerr – NASA has to have an acronym for everything 🙂 ).

The latter had been recently restored as a direct result of a project initiated and driven by Kranz in 2017 in memory of Apollo and so many of his colleagues who have since passed away (the most recent, sadly, being Robert Edwin “Ed” Smylie whose team worked alongside Kranz’s White Team to make sure the Apollo 13 astronauts returned to Earth safely, and who passed away on April 21st, 2025). Fully deserving of the AAS award, Gene Kranz remains one of the stalwarts of NASA’s pioneering heydays.