China’s space programme is perhaps the most aggressive in the world in terms of ambitions and speed of development. In the last two decades, the country has been embarked on one of the most forward-thinking human spaceflight programmes, quickly moving from two small orbital laboratories to a fully-fledged space station whilst setting its eyes firmly on the Moon. At the same time, it has shown itself to be the equal of both the United States and Europe in the field of robotic exploration of the Moon and Mars, whilst also seeking to match the United States in pioneering the use of uncrewed reusable vehicles.

Most notably in this latter regard has been the Shenlong orbital vehicle, which I first wrote about in 2023, and which completed its second 200+ day orbital mission September 2024. Whilst not as long in duration as those of America’s X-37B, which it matches in terms of size and secrecy, Shenlong could be broadly as capable. And it will soon be joined by a second Chinese automated spaceplane, one with a similar purpose to America’s upcoming Dream Chaser vehicle.

Called Haolong, this new vehicle is one of two finalists in an 18-month selection process initiated by the China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) to determine the next generation of resupply vehicles intended to support the country’s Tiangong space station. In May 2023, CMSEO sought proposals from government agencies and China’s growing private sector space industry for vehicles capable of delivering a minimum of 1.8 tonnes of materiel to the Tiangong space station at a cost of no more than US$172 million per tonne. From the 10, in September 2023 four were selected to move forward to a more intensive design and review phase lasting just over a year, with the potential for two of them to be picked for full vehicle development.

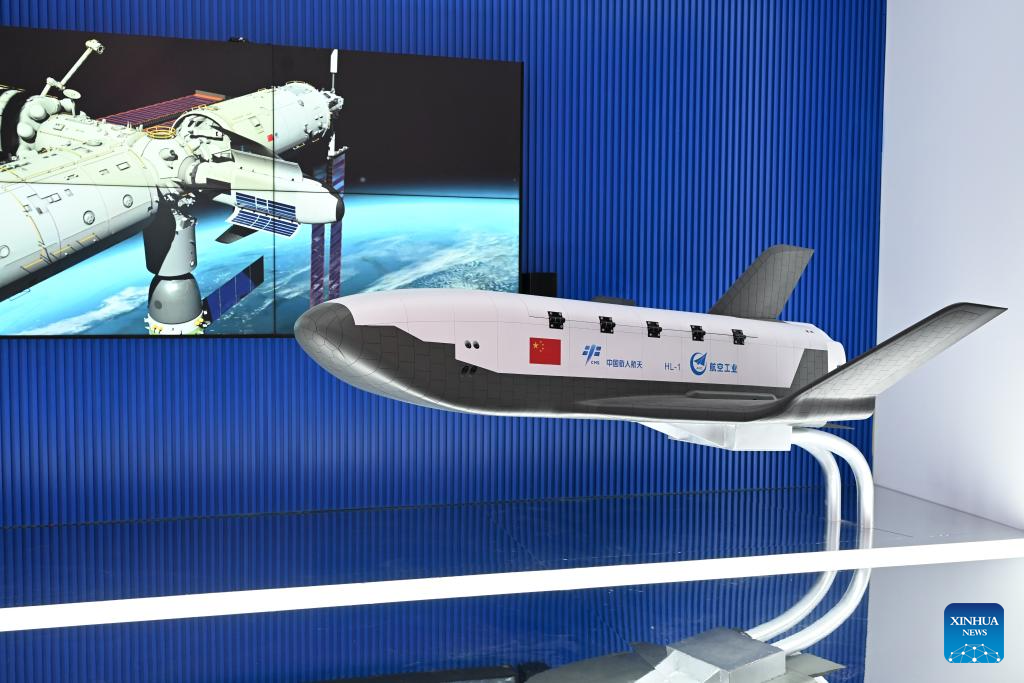

On October 29th, 2024, the winning proposals were announced, with the Haolong spaceplane immediately gaining the the most interest due to its nature and the fact it was heavily promoted at China’s annual Zhuhai Air Show, complete with videos showing it in operation and images showing the full-size proof-of-concept development model.

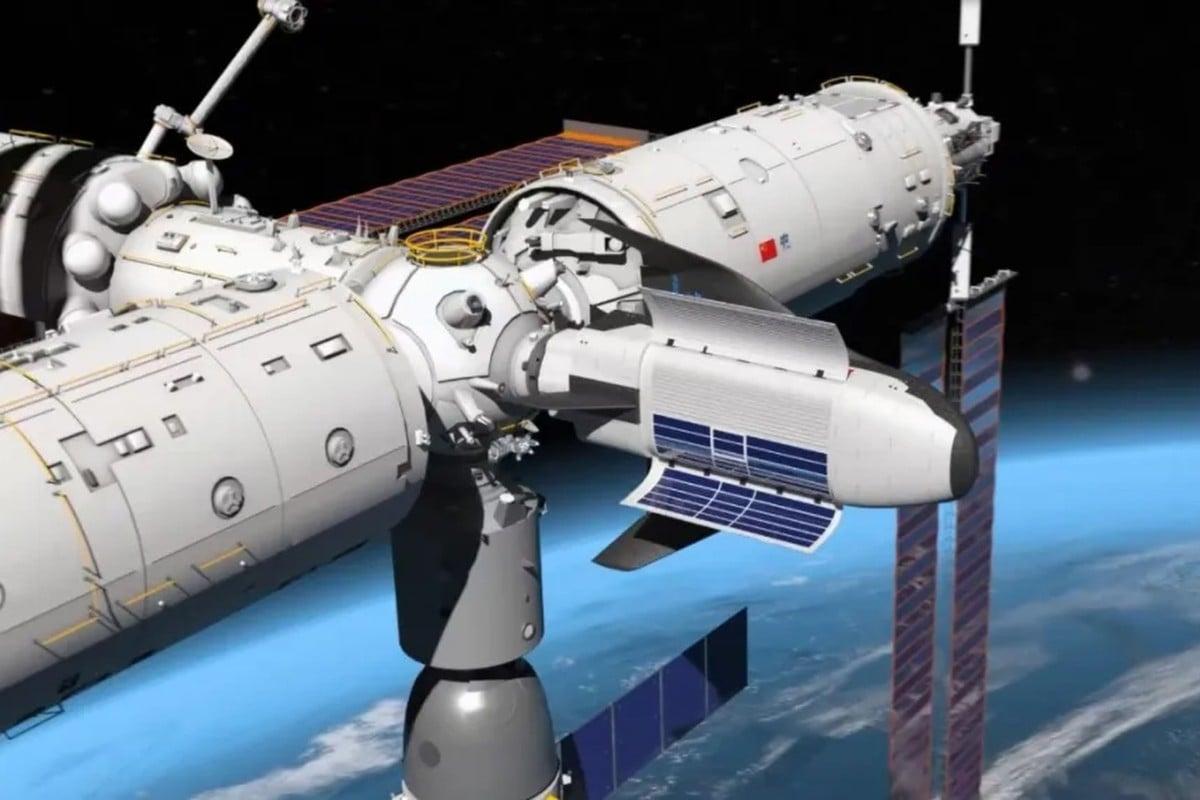

Haolong’s development is being undertaken by an unlikely source: the Chengdu Aircraft Design and Research Institute, operated by the state-owned Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC). Neither Chengdu, which is largely responsible for military aircraft development, nor AVIC has been involved in space vehicle development until now. At a length of 10 metres and a span of 8 metres with its wings deployed, Haolong is very slightly longer and wider than America’s Dream Chaser (9 metres long with a 7-metre span). Like the American vehicle, Haolong is designed to be vertically launched via a rocket, its wings folded to fit within a payload fairing, ready to be deployed once it reaches orbit and separates from its carrier rocket.

Exactly what to overall payload capability for the vehicle might be is unclear; Chengdu have only confirmed it will be able to lift the required 1.8 tonnes to orbit. This is less than one-third the total load carried by the current automated (and completely expendable) Tianzhou resupply vehicle, which can carry up to 6 tonnes to orbit – a capacity Dream Chaser can match.

However, given Haolong’s size and pressurised cargo space – coupled with the fact that the CMSEO requirement included a provision the new resupply vehicles can dispose of / return to Earth up to 2 tonnes of waste / materiel – it would seem likely Haolong’s all-up payload capability is liable to be above the 1.8 tonne minimum should it ever be required to fly heavier loads.

But even if this isn’t the case, Haolong still scores over Tianzhou, as it’s all-up mass is expected to be less than half that of the older vehicle, potentially enabling it to be launched by a selection of Chinese rockets rather than being restricted to the expensive Long March 7. It could, for example even come to be launched atop the semi-reusable Long March 2F (if this enters production), or the rumoured semi-reusable variants of either the Long March 8 or long March 12B, as well as the expendable versions of Long March 2.

Details of the second vehicle to be selected, the Qingzhou cargo spacecraft, are somewhat scant, including its overall reusability. However, it will be launched via the upcoming Lijian-2 rocket being developed by CAS Space. The latter is commercial off-shoot of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, so technically its use as the launch vehicle for a space station resupply craft marks the first time a commercial entity will participate directly in China’s national space programme.

Long March 9: China’s Answer to Starship / Super Heavy?

Also present at the Zhuhai Air Show were further models of China’s in-development super heavy launch vehicle, the Long March 9 (Changzheng 9 or CZ-9) booster, together with the first models of China’s answer to (or near-clone of, if you prefer) the SpaceX Starship vehicle.

First announced in 2011, Long March 9 has been through a number of iterations and design overhauls. As first envisaged, the vehicle would comprise a 10-metre diameter core stage supported by up to four 5-metre diameter liquid-fuelled boosters (essentially Long March 10 first stages), giving it the ability to lift an upper stage with a payload capacity up to 140 tonnes to low-Earth orbit (LEO). With minor variations, this remained pretty much the baseline design until around 2019.

A substantial redesign then appeared in 2021. This saw the elimination of the strap-on boosters and the first stage diameter increased 10.6 metres. To compensate for the loss of the strap-on boosters, the first stage of the vehicle had its original four engines replaced by 16 kerosene / liquid oxygen (LOX) motors, each one generating some 300 tonnes of thrust at sea level, allowing it to haul up to 160 tonnes of payload up to LEO.

Then in 2022, the decision was made to make the first stage of the rocket reusable. The LOX / kerosene motors were swapped for 26 of the more efficient YF-135 methane / LOX motors, the exact number compensating for the reduction in overall thrust. However, as 26 main engines required an 11-metre diameter first stage to fit them and their additional propellants, the design was then scaled back to keep the 10.6 metre diameter, and the number of motors reduced to 24 first stage engines. A further change at this point small the vehicle’s optional third stage increased in diameter from 7.5 metres to 10.6 metre as well, unifying all three stages.

This design carried over to 2023, where it was displayed at that year’s Zhuhai Air Show. However, the engine configuration had again changed for the first stage, with 30 of the more compact YF-215 motors now being used. In this configuration, Long March 9 was touted as being capable of delivering somewhere over 100 tonnes but less than 160 tonnes of payload to LEO in a two-stage variant and between 35 and 50 tonnes of payload to the Moon in a 3-stage version.

Also revealed at the 2023 Air Show were drawings of CALT’s take on the SpaceX Starship. At the time, the idea was defined as a “possible” iteration of the Long March 9 design, and unlikely to be ready for use – if pursued – until the 2040s. However, at the 2024 Air Show held in early November, it was clear CALT is invested in making a fully reusable Long March 9 launch system; on display were a set of models, one showing the Long March reusable first stage with the “starship” vehicle sitting on top of it, with two smaller models showing the “starship” vehicle on the lunar surface and a Long March 9 first stage resting on its “catch gantry” at the end of a flight.

According to CALT representatives at the show, work has now commenced on fabricating the first Long March 9 test vehicle, indicating the core design for the rocket’s first stage is now largely finalised, and the focus will initially be on developing this and the expendable second and third stages, with the first launch of an integrated rocket targeted for 2030. However, the representatives also indicated that the development of the reusable upper stage vehicle is seen as more integral to China’s lunar aspirations, and that they are looking to introduce it possibly as soon as the mid-to-late 2030s.

While making no secret of the fact they are directly emulating SpaceX with their design, CALT noted their vehicle would be more flexible in its application. As well as being able to deliver 100 tonnes to LEO, it was suggested it will be able to deliver smaller payloads to other orbits – such as MEO, GEO, GTO and SSO, and deliver as much as 50 tonnes to TLI, all apparently without the need for on-orbit refuelling (which Starship currently requires in all these cases).

If the lack of refuelling is accurate, then it suggests CALT are considering different internal layouts for their “starship”, such as utilising payload space for additional propellant tanks to enable their vehicle a wider range of operational capabilities; however, until CALT are more forthcoming on exactly how they envisage vehicle operations to work, this is purely speculative.

Reaction Engines in Administration

Reaching orbit using rockets – even reusable ones – is a costly business. Rockets require complex, high-performance (and costly) motors, have to carry a lot of propellants to feed them, and require a lot of specialised infrastructure to operate them. Because of this, one of the holy grails of access to space has been the SSTO – single stage to orbit – vehicle; a craft capable of taking off in a manner akin to that of an aircraft, reaching orbit and then returning to Earth and again landing like a conventional aircraft.

In the 1980s, Britain in particular worked on an SSTO concept called HOTOL (Horizontal Take-Off and Landing), an uncrewed vehicle roughly the size of an MD-80 airliner. It would have utilised a unique air-breathing engine underdevelopment by Rolls Royce (the RB-545) to carry up to 8 tonnes of payload to orbit , using the air around it as an oxidiser for its rocket motors, mixing it with on-board supplies of liquid hydrogen until the atmosphere became too rarefied for this, and the engines would switch to using on-board LOX with the liquid hydrogen. But despite initial government backing, interest from the European Space Agency and the United States, HOTOL floundered and ultimately died in 1989, and Rolls Royce shelved development of the RB-545.

Undeterred by this, one of HOTOL’s originators, Alan Bond, co-founded Reaction Engines Ltd (REL), a company dedicated to developing both a new air-breathing engine to supersede the RB545 and a new SSTO spaceplane to use it. The motor, called SABRE (Synergetic Air Breathing Rocket Engine) and the vehicle, called Skylon, have been in development ever since, with SABRE in particular seeing much progress and both national and international interest. In fact, as recently as 2019, things looked remarkably rosy for SABRE and Reaction Engines.

This is why the announcement that REL had entered administration, with all staff laid-off, is deeply saddening. An eight-week process has commenced to either restructure or sell the company; if neither proves viable, it will enter liquidation and all assets sold-off. No formal reason for the company’s failure to continue to gain funding has been given; however, it has been suggested that the fact SABRE and Skylon would only be able to operate from specially reinforced runways, rather than any suitably-equipped airport facility, may have been a contributing factor.

NASA and Roscosmos at Loggerheads over ISS Leak

For the last five years the International Space Station (ISS) has been suffering from an atmospheric leak within one of its oldest modules, the Russian Zvezda Service Module. Launched in 2000 as the third major element of the space station, Zvezda is actually approaching its 40th birthday, the core frame and structure having been completed in 1985 when Russia was still engaged in its Mir space station programme.

As such, the unit is well beyond its operational warranty period, and since 2019, the short airlock tunnel connecting the Zvezda’s primary working space with the aft docking port has been suffering an increasing number of microscopic cracks that have allowed the station’s atmosphere to constantly leak out. Whilst the overall volume of atmosphere lost is small, by April 2024 it had reached a point where attempts to patch some of the cracks were made. While this did reduce the amount of air being lost for a short time, the volume has once again be rising of late.

Whilst the leaks are still far short of being any risk to the station’s crew, NASA and Roscosmos cannot reach an agreement on either their root cause or their potential to become a significant hazard. Roscosmos remains of the opinion that the cracks are purely down to thermal contraction as the module expands and contracts as it passes in and out of the Sun’s light and heat, and therefore no different to the thermal wear on all other parts of the station.

However, while agreeing agreeing thermal expansion and contraction has a role to play in the leaks, NASA does not agree that it is the only cause. Instead, they see the continued use of the aft docking port – primarily used to receive Progress resupply vehicles – as putting additional stress on the tunnel’s walls, and this, couple with the aging of the module in general and the thermal expansion / contraction is causing the cracks. What’s more, NASA is concerned that if use of the after docking port continues, it is elevating the risk of a high-rick failure within the tunnel which could seriously compromise station operations.

Given this, NASA would like to see Roscosmos discontinue the use of the docking port – which Roscosmos argues is not necessary. While both agree the issue is unlikely to result in a complete and catastrophic failure within the tunnel culminating in a lost of the station as a whole; NASA engineers and mission controllers are concerned that any failure within the tunnel could impact operations throughout the station. As such, they have ordered the hatch between the Russian elements of the ISS and the US / international modules to be kept closed other than during crew passage between the two sections of the station.