NASA finally got its flagship Europa Clipper mission away on Monday, October 14th, with the lift-off of its Falcon Heavy booster having been delayed four days, courtesy of Hurricane Milton.

The launch occurred at 16:06 UTC from the SpaceX launch facilities at LC-39A, Kennedy Space Centre. It marked the start of a 5.5 year flight to Jupiter for the spacecraft, which as I covered in a recent Space Sunday article will study Jupiter’s icy moon of Europa for about 4 years. It will be joined in this effort by Europe’s JUICE mission, which although launched 18 months ahead of the NASA mission, will arrive a year after it, and will also study Jupiter’s two other “icy world” moons: Ganymede and Callisto.

Once at Jupiter, Europa Clipper – the spacecraft – will orbit the planet, not the moon, making periodic fly-bys of the latter. As I previously explained, this is to both minimise its exposure to the extremely harsh radiation regime immediately surrounding Jupiter (and enclosing Europa) which would burn-out the vehicle’s electrical systems in about 6 months, and also to maximise the time available for it (between 7 and 10 days, rather than mere minutes were it orbiting Europa) to transmit the data gathered during each fly-by back to Earth.

The mission is one of NASA’s most expensive robotic undertakings yet, with an estimated total lifecycle cost (including the four years of operations studying Europa) of US $5.2 billion.

Following launch, none of the three core stages of the rocket – all of them Falcon 9 first stages – were slated for recovery, and five minutes after lift-off the upper stage of the rocket separated and fired its engine whilst also jettisoning the payload shroud protecting the Europa Clipper spacecraft, as it continue to carry the latter up to an initial orbit.

This parking orbit was used to carry out checkouts on the space vehicle as it coasted around the Earth for some 40 minutes prior to the upper stage motor re-lighting for a three minute burn to push its payload onto its initial trajectory away from Earth. Payload separation then came just over an hour after launch, temporarily breaking communications with the spacecraft which had up until that point been using the communications relay on the Falcon upper stage to report its status.

Signal acquisition took five minutes as the spacecraft had to first “warm up” its communications systems via its onboard batteries. Once the signal had been obtained, initial flight data information and vehicle operating telemetry were returned to mission control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California, the latter revealing a minor problem in the spacecraft’s propulsion system, but which was not interfering with general operations.

We could not be more excited for the incredible and unprecedented science NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will deliver in the generations to come. Everything in NASA science is interconnected, and Europa Clipper’s scientific discoveries will build upon the legacy that our other missions exploring Jupiter — including Juno, Galileo, and Voyager — created in our search for habitable worlds beyond our home planet.

– Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters, Washington

With the initial check-out complete, the command was sent for the vehicle to start unfurling its two huge solar array “wings”, the largest NASA has ever flown on a deep space mission (with a total vehicle/ array span just slightly smaller than that of Europe’s Rosetta mission). This was a gentle operation, finally completed some 6 hours after launch, allowing the craft to start generating up to 600 watts of electrical output.

The spacecraft is now heading away from Earth on a heliocentric orbit which will allow it to fly-by Mars in March 2025 prior to a return to Earth in December 2026. It will use Earth’s gravity to assist it on its way to Jupiter, which it will reach in April 2030.

Skyrora First UK Vertical Launch?

Scottish rocket start-up, Skyrora Now looks to be taking pole position in the race to be the first entity to launch a commercial rocket from British soil. In October, the company announced that after months of delay – not all of them related to itself – it expects to receive a launch vehicle license from the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) in December 2024 or January 2025. This will allow its first launch to take place in the spring of 2025, from the UK’s SaxaVord Spaceport located on the Lamba Ness peninsula of Unst, the most northerly of the inhabited Shetland Islands.

Based in Edinburgh, Scotland, Skyrora has been operating since 2017, and already has something of an impressive record, developing two sub-orbital test bed vehicles Skylark Nano and Skylark Micro, which helped pave the way for their Skylark L two-stage sub-orbital rocket, capable of lifting payloads of up to 60 Kg to attitudes of around 100km for micro-gravity research.

The company is also working on the tree-stage version of the vehicle, called the Skylark XL, capable of placing payloads of up to 315 kg into a 500-km low-Earth orbit (LEO). In addition, Skyrora has also been developing its own 3D printed engines for its rockets, and plans to offer a “space tug” vehicle along with Skylark XL. This tug will be capable of remaining in orbit post-launch and used to either remove space debris from orbit, and / or replace / maintain satellites in orbit by giving them a little boost.

I’ve covered Skyrora a couple of times in this column, notably in October 2022, when the company attempted its first Skylark L launch. This actually took place from Iceland (as regulatory approval for hosting launches from UK soil had not at that time been granted), and whilst it was ultimately unsuccessful as a result of a software error, it did demonstrate a further unique aspect of Skylark L: a fully mobile launch platform and control facility allows the company to ship a rocket and its launch systems pretty much anywhere in the world and complete a launch without the need for any permanent supporting launch infrastructure.

As well as flying the Skylark L from SaxaVord, Skyrora also intend to use the facilities at the spaceport for its Skaylark XL original launcher, thus becoming one of a number of commercial ventures set to use SaxaVord, which gained its operator’s license from the CAA in May 2024.

In fact, at the time the license was granted, it was widely anticipated that Germany’s Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA) would be the first to launch from the site. Holding a long-term lease on the facilities most northerly launch pad – called Freddo – RFA commence static fire tests of the first stage of the rocket they hoped to fly, in June 2024, with an initial test of 4 of the nine motors. They then planned a further test of all nine engines in August 2024, with the aim of then assembling the entire vehicle and launching at the end of summer. Unfortunately, and as I reported at the time, the second static fire test resulted in the complete loss of the stage 38 second after motor ignition. RFA now expect to make their first launch attempt from SaxaVord in August 2025.

Starliner: 1st Operational Flight Postponed

Following the uncrewed return for Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner Calypso at the end of a frustrating Crew Flight Test (CFT) which saw significant issues with the vehicle’s service module and its propulsion systems, NASA has confirmed it will not have the vehicle participate in either of the planned crew rotation flights planned for 2025.

The news is hardly surprising; NASA wants to give Boeing and their propulsion system partner Aerojet Rocketdyne as much time as possible to fully diagnose and correct a multitude of problems with the service module propulsions systems – from overheating, through leaks in purge systems to unexpected wear-and-tear on valves – and then determine how best to get the system properly certified for operational use.

In July 2024, prior to Calypso returned to Earth, the US Space Agency made an initial decision to swap the planned crew flights for 2025. Originally, Starliner 1, carrying a crew of four to the ISS, had been due to fly in February 2025 – but NASA swapped that out in favour of SpaceX Crew 10. This left Starliner 1 occupying the late July / early August slot; however, as well as swapping the slots over, NASA also instructed SpaceX to bring forward preparations for its 2026 Crew 11 flight, thus allowing the agency to to seamlessly swap to flying a crew on SpaceX Crew Dragon if Starliner was not in a position to fly a full mission.

Now, in the wake of further deliberation, NASA has opted to fly the July/August 2025 mission using SpaceX Crew 11, meaning the earliest Starliner is likely to fly an operational mission to the ISS will be 2026. However, this does not mean Starliner will not fly at all in 2025; rather it means that NASA have given themselves and Boeing additional space in which to fly a further Crew Flight Test of the vehicle, should the agency decided one is warranted ahead of any final vehicle certification, and to be able to plan and fly any such mission again with minimal disruption to existing schedules.

Space Debris and Re-Entry: Hazards and Pollution

There is an estimated 150 million pieces of space junk / debris orbiting the Earth ranging in size from around 1 cm across to entire satellites and spent rocket stages, all of which constitutes a growing hazard for space operations, crewed and uncrewed. An increasing number of operational satellites routinely have to change altitude / velocity to avoid collisions with such objects – or at least, with those that can be accurately tracked.

On top of that there are hundreds of millions of pieces of debris in the millimetre(-ish) range zipping around the Earth we simply cannot track, but which pose and equal amount of danger – witness what happened to Soyuz MS-22 in December 2022, which what is believe to be a millimetre-sized piece of Micrometeoroid and Orbital Debris (MMODs) punched its way through a vital cooling system radiator.

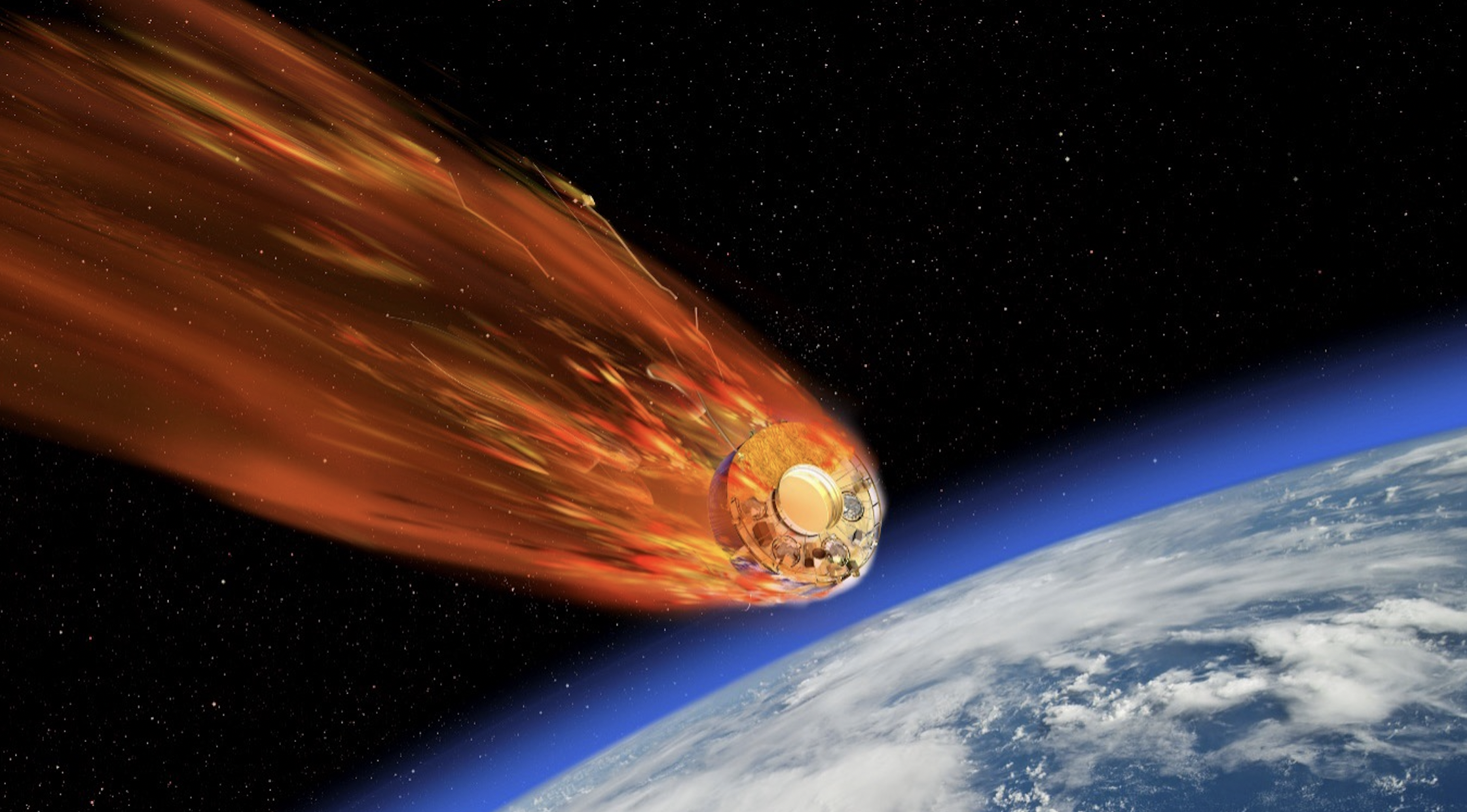

Things like MMODs are really hard to mitigate, and while getting rid of larger debris is a problem multiple companies are actively working on, by far the most common means of disposing of unwanted satellites and used bits of rockets and spacecraft is to push them back into the upper atmosphere and let them burn up. However, there is now growing evidence that this approach is neither wise or sustainable, with studies revealing increasing signs that doing so beginning to have a lasting detrimental impact on the atmosphere, and by extension, the climate, both of which are already subject to other aspects of space launch activities.

In just 10 years, the volume of satellites and rocket elements burning-up in the upper atmosphere has doubled. In their wake they leave soot from engine exhausts, aluminium oxides capable of altering the planet’s thermal balance in favour of faster greenhouse warming (as well as the return of ozone destruction). In particular, three separate studies have shown that concentrations of aluminium oxides in the mesosphere and stratosphere — the two atmospheric layers above the lowest layer, the troposphere have been measurably rising in the same period. One of these reports goes so far as to note that if the current rate of disposal of space junk through atmospheric burn-up continues for as little as 20-30 more years, the volume of aluminium oxides in the upper atmosphere could increase by 650%.

And this rate of disposal is not to much likely to continue in the next couple of decades – but increase, thanks to the ever increasing number of “megaconstallations” of thousands of satellites in low Earth orbit.

To take Starlink as an example (and as cited by UK-based Space Forge). Since 2019, SpaceX has launch thousands of Starlink satellites which are supposed to be able to remain in orbit for 5 years before re-entering the atmosphere. However, such has been the pace of development, SpaceX has been actively disposing its older, unwanted Starlink units by de-orbiting them to to make space for newer units, reaching a point where they are now responsible for some 40% of all debris re-entering the Earth atmosphere and being incinerated. This equates to half a tonne of incinerated trash – much of it aluminium oxide – being dumped in the mesosphere and stratosphere every day, just by Starlink. And that’s just with an operational fleet of 6,000 satellites; what – researchers ask – will it be like if SpaceX are allowed their requested 40,000 units in orbit?

And while they are singled-out, SpaceX are not alone, both One Web and Amazon are deploying their own (admittedly fewer in number) constellations which will also likely go through the same continuous evolution at Starlink; then there are military constellations, European constellations and the potential huge Chinese Thousand Sails megaconstellation. Thus, the issue is not going to be diminishing any time soon.

Already researchers have calculated that the amount of ozone depletion directly related to space launch operations is slowly increasing. Not only are there far more satellites being pushed back into the atmosphere – there are more rocket stages going the same way, filled with soot, aluminium oxides, alumina particles in general and chlorine, which are all being dispersed in the upper atmosphere. Again, to take SpaceX as an example: they are performing some 100 launches a year when less than a decade ago the total number of global launches was maybe two dozen. That’s 100 extra upper stages burning up in the atmosphere – from just one company. Add that to the pollutants pushing into the atmosphere during launch from the liquid kerosine SpaceX uses with Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, and it is understandable why researchers pin around 12% of ozone depletion from space related activities just on SpaceX.

But again, the company is hardly alone – and through a switch to methane (which despite itself being a greenhouse gas, burns so cleanly in rocket motors so as to produce very little measurable pollution in the scheme of things), they are attempting to reduce that aspect of their footprint. ESA, Roscosmos, JAXA, ULA, NASA, the Indian space industry – even the likes of Virgin Galactic – continue to dumping harmful waste products into the atmosphere through their use of solid rocket motors and hybrid propellants in their launch vehicles / space planes. These perhaps doe the most significant damage to the atmosphere each and every time they are used.

The problem here, of course is how to regulate without suffocating. And it that, the issue of atmospheric pollution as a result re-entry burn-up is particularly thorny. For while there are multiple national requirements and international agreements relating to environmental protection in countries operating launch services, none of them extend to protecting the atmosphere against the potential harmful impact of using it as a convenient trash incinerator.