China became the first nation to successfully return samples gathered from the Moon’s far side to the Earth on June 25th, when the capsule carrying those samples made a successful soft-landing on the plains of Inner Mongolia.

The capsule had been launched to the Moon on May 3rd as part of the Chang’e 6 mission (see: Space Sunday: Starliners and samples), which targeted an area within the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin, where both the United States and China plan to lead separate international projects to establish permanent bases on the Moon. The craft initially entered a distant lunar orbit on May 8th, taking around 12 hours to complete a single pass around the Moon. The orbital was then gradually lowered of a period of several days prior to the mission settling into a period of observation of the landing site from an altitude of just over 200 km, allowing mission planners on Earth the opportunity to further confirm the proposed area of landing was suitable for the lander.

Then, on May 30th, the lander vehicle with is cargo of sample-gathering tools, ascent vehicle with sample canister and mini-rover detached from the orbiter / return craft and gently eased into its own obit some 200 km above the Moon, from which it could make its final descent.

Landing occurred 22:06 UTC, the vehicle using its on-board autonomous landing system to avoid any land minute hazards and bring itself down to just a couple of metres above the lunar surface. At this point, the decent motors were shut off in order to avoid their exhausts containing the surface material from which samples would be obtained, and the lander dropped into a landing, the shock of impact at 22:23 UTC absorbed by cushioning systems in its landing legs.

The surface mission then proceeded relatively rapidly thereafter. The mini-rover, was deployed not long after landing. Described as a “camera platform” rather than a fully-fledged mini-rover like the Yutu vehicles China has previously operated on the Moon. Once deploy, the rover trundled away from the lander to take a series of images to help ensure it was fit for purpose post-landing. The rover was also able to observe the deployment of the lander’s robot arm with its sample-gathering system, and make remote measurements of surface conditions around the lander.

It’s not clear precisely when the samples were gathered, but at 23:38 UTC on June 3rd, the ascender vehicle with just under 2 kg of samples of both surface material and material cored by a drill from up to two metres below the surface, lifted-off from the back of the lander and successfully entered lunar orbit, rendezvousing and docking with the return vehicle at 06:48 UTC on June 6th. The transfer of the sample capsule to the return vehicle took place shortly thereafter, and the ascender was then jettisoned.

Throughout most of the rest of June, China remained largely quiet about the mission. However, based on orbital calculations and observations by amateurs, it appears likely the return vehicle fired its engines to break out of lunar orbit on June 21st, then fired them again to place itself into a trans-Earth injection (TEI) flight path, the vehicle closing on Earth on June 25th. As it did so, the 300 kg Earth Return unit separated and performed a non-ballistic “skip” re-entry.

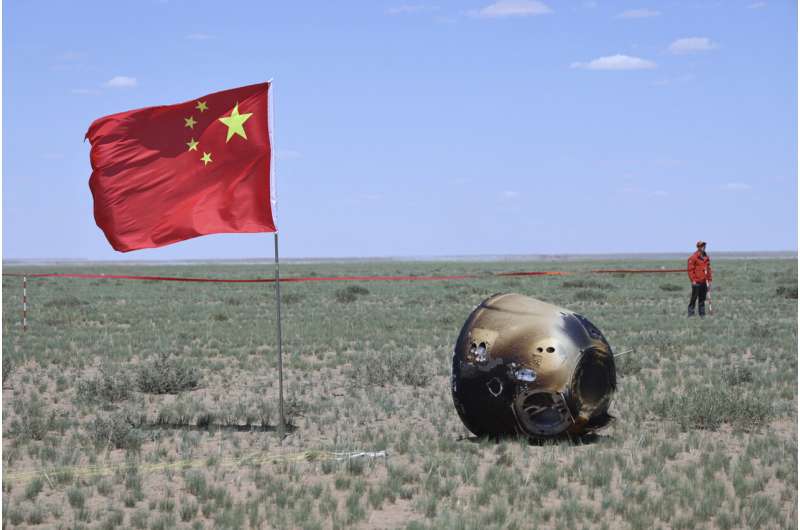

This is a manoeuvre in which a spacecraft reduces the heating loads placed on it when entering the atmosphere by doing so twice; the fist manoeuvre see it skim just deep enough into the denser atmosphere to shed a good deal of its velocity before it rises back up again, cooling itself in sub-orbital ballistic cruise, at the end of which it drops back into the denser atmosphere for re-entry proper. Doing things in this way means that spacecraft returning from places like the Moon do not have to have hugely mass-intensive heat shields, making them more mass-efficient. For Chang’e 6, the skip was performed over the Atlantic, the ballistic cruise took place over northern Europe and Asia before it re-entered again over China and then dropped to parachute deployment height for a touchdown within the Siziwang Banner spacecraft landing area in Inner Mongolia, the traditional landing zone for Chinese missions returning from space.

Following recovery, the capsule was airlifted to the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) in Beijing. Then, on June 27th during a live television broadcast, the capsule was opened and sample canister very carefully removed so it could be transferred to a secure and sterile facility for future opening. Afterwards, Chinese officials responsible for the mission gave an international press briefing in which scientists, agencies and research centres from around the world were invited to request samples of the 1.935 kg of material gathered by the probe, the invitation made along much the same lines as made following the rear of the Chang’e 5 samples in 2020.

What makes these samples particularly enticing to scientists is that they are far a part of the Moon very different in terms of morphology and geology to that of the lunar near side, from where all sample of material have thus far been gathered. As such, the Chang’e 6 samples are of significant interest not only because of what they might reveal about the region where humans will – in theory – one day be living and working, but also for what they might reveal about what is currently a genuinely unknown geology and morphology on the Moon, as thus further reveal secrets about it’s formation.

However, one agency which may not directly benefit from China’s offer is NASA. The 2011 Wolf Amendment prohibits the US space agency and its research centres to use government funds or resources to engage in direct, bilateral cooperation with agencies of the government of the People’s Republic of China, or any affiliated organisations thereof, without the explicit authorisation from both the FBI and Congress. Such authorisation was not granted in the wake of the Chang’e 5 sample return mission, and so it seems unlikely it will be given for this mission, no matter what the scientific import of the samples.

That said, the Wolf amendment does not prevent non-NASA affiliated US scientists and organisations from being involved in studying samples from the mission. Following Chang’e 5, for example, US scientists joined with colleagues from the UK, Australia and Sweden in a consortium which obtained samples from that mission, allowing several US universities to be involved in studying them. This is something that could happen with regards to the Chang’e 6 samples, once they start being made available by China.

Russian Satellite Break-Up Prompt ISS Shelter In Place – Including Starliner

Despite efforts by NASA, much of the media incorrectly continues to present the idea that two NASA astronauts – Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams are “stranded” on the International Space Station (ISS) due to issues with their Boeing CST-100 Starliner Calypso. However, as I noted in my previous Space Sunday article, this is simply not the case (see: Space Sunday: capsules, spaceplanes and missions). Yes, NASA is being cautious around the Starliner vehicle’s issues, but this does not mean the vehicle “cannot” return to Earth.

In fact, practical evidence of NASA’s confidence in the vehicle to make a safe return to Earth came on June 27th, when the entire crew of the ISS were ordered to prepare for s sudden evacuation of the station.

The emergency procedure – referred to as shelter in place – was triggered when the destruction of a decommissioned polar-orbiting Russia satellite was detected by debris-tracking organisation LeoLabs. Producing a cloud of around 180 trackable pieces of debris, the event was traced to the orbit of the 6.5 tonne Russian Resurs P1 spacecraft.

Orbiting at some 470 km, the orbit of the satellite periodically intersected that of the ISS. As the explosion had caused a new orbital track for the resultant debris, it was necessary for the US Space Command to re-assess the passage of both the ISS and the growing debris cloud to ensure there would be no “conjunction” (that’s “collision” to you and me). As a precaution against this being the case, at 02:00 UTC, the entire Expedition crew were ordered into their spacesuit and then into their vehicles and power them up ready for a rapid departure, but not actually seal hatches and undock – and this included Williams and Wilmore on the Starliner.

While all this sounds dramatic, it is not; shelter in place has been the order on a number of occasions when there has been the risk of a collision with debris. Perhaps the most famous up until now came in 2021, after some idiot in the Kremlin ordered an unannounced test of an anti-satellite (A-SAT) missile, resulting in the destruction of another decommissioned Russian polar-orbiting satellite, this one causing a debris cloud of almost 2,000 trackable fragments at an orbital altitude close to that of the ISS.

As news broke of the June 27th event, there was some short-lived concern the same A-SAT foolishness had occurred with Resurs P1; however, this was quickly ruled out by the United States Space Command, as a review of data showed there was no evidence of any missile firing in the period ahead of the satellite disintegrating. After analysis of the debris cloud’s orbit and period aby both USSC and LeoLab, the New Zealand based debris tracking agency which initially reported the loss of Resurs P1, it was determined there was no threat to the ISS, and the crew were informed they could secure their spacecraft and return to the station after around an hour.

It is currently believed the destruction of the Russian satellite was due to it not undergoing “passivation” when it was decommissioned at the end of 2021. Whilst not mandatory or 100% effective, “passivation” has been common since the 1980s and involves the removal of any potentially energetic elements of a decommissioned satellite to reduce the risk of future break-up as a result of an explosion or similar. Typically, batteries are ejected so they will eventually burn-up in the atmosphere, whilst remaining propellants are vented into space.