Curiosity, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover, arrived on Mars in 2012 – and helped kick-off Space Sunday in this blog. Since then, the mission has been a resounding success; even now the rover continues climbing the flank of “Mount Sharp” (officially designated Aeolis Mons), the 5km high mound of sedimentary and other material towards the centre of Gale Crater where it landed, revealing more and more of the planet’s secrets.

Curiosity, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover, arrived on Mars in 2012 – and helped kick-off Space Sunday in this blog. Since then, the mission has been a resounding success; even now the rover continues climbing the flank of “Mount Sharp” (officially designated Aeolis Mons), the 5km high mound of sedimentary and other material towards the centre of Gale Crater where it landed, revealing more and more of the planet’s secrets.

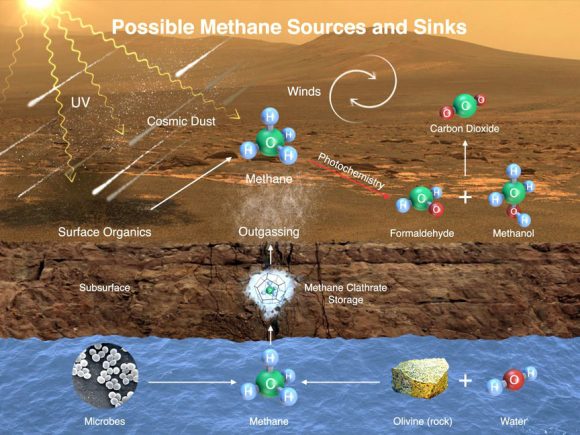

However, there has been one long-running mystery about Curiosity’s findings as it has traversed Gale Crater and climbed “Mount Sharp”. As it has been exploring, the rover has at times been sensing methane in the immediate atmosphere around it. Methane can be produced by both organic (life-related) and inorganic means – so understanding its origins is an important area of study. Unfortunately, Curiosity is ill-equipped to easily detect and investigate potential sources of the gas; that’s more a job for its sibling, Perseverance. As such, the overall cause of the methane Curiosity has detected remains a mystery.

And it is a mystery compounded in several ways. For example: the methane often only seems to “come out” at night; the amount being detected seems to fluctuate with the seasons, suggesting it might be linked to the local environmental changes; but then, and for no apparent reason, Curiosity can sometimes sniff it in concentrations up to 40 times greater than it had a short time before – or after. A further mystery is that whilst Curiosity detects methane in the atmosphere around it, it is the only vehicle on Mars to thus far do so to any significant extent.

Further, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), a vehicle specifically designed to sniff out trace gases like methane throughout the Martian atmosphere has, since 2018 when it started operations, almost totally failed to do so. All of which suggests that whatever Curiosity is encountering is unique to the environment of Gale Crater – and possibly to “Mount Sharp” itself.

Given this, scientists have been trying to determine the source of methane, but so far, they haven’t come up with a specific answer. However, current thinking is that it has something to do with subsurface geological processes involving water – with one avenue of research suggesting that it is curiosity itself that is in part responsible for its release, particularly when it comes to the sudden bursts of methane it detects.

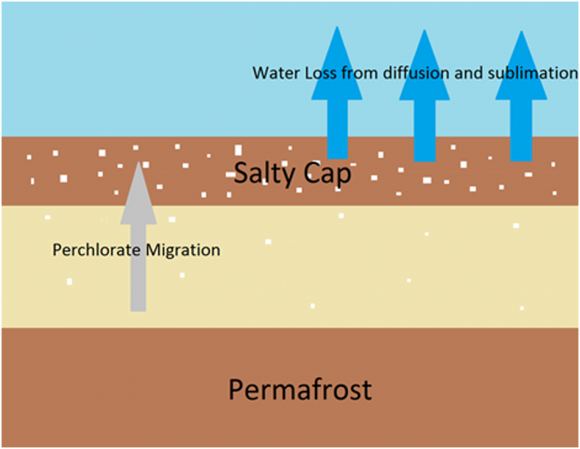

A recent study by planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre has demonstrated that any methane within Gale Crater, whether produced by organic or inorganic means, might actually be following the path outlined in the diagram above – but is getting trapped within the regolith by salt deposits before it can ever be outgassed. However, this was not the original intent of the study, which first started in 2017.

At that time, a team of researchers at NASA’s Goddard Research Centre led by Alexander Pavlov, were investigating whether or not bacteria could survive in an analogue of the kind of regolith Curiosity has encountered across Gale Crater and within environmental conditions the rover has recorded. Their results were inclusive in terms of organic survivability, but they did find that the processes thought to be at work within Gale Crater could lead to the formation of solidified salty lumps within their analogue of Martian regolith.

And there the matter might have rested, but for a report Pavlov read in 2019, as he noted in discussing the results of his team’s more recent work.

We didn’t think much of it at the moment. But then MSL Curiosity detected unexplained bursts of methane on Mars in 2019. That’s when it clicked in my mind. We began testing conditions that could form the hardened salt seals and then break them open to see what might happen.

– Alexander Pavlov, Planetary Scientist, NASA Goddard Research Centre

As a result, Pavlov and his team went back to their work, looking at the nature of the sedimentary layers of “Mount Sharp”, the amount of water ice they might contain, etc., and started testing more regolith analogues to see what might happen with different concentrations of perchlorates within the water ice. Starting with around a 10% suspension (much hight than has ever been found on Mars), the team gradually worked down to under 5% (closer to Curiosity’s findings, but still admittedly high). In all cases, they found that not only did the perchlorates leach out of the escaping water vapour as it passed through the reoglith analogue to form frozen lumps, it tended to do so at a fairly uniform depth the lumps combining over time – an average of 10 days – to form what is called a “duricrust” layer.

Duricrusts are extensive (in terms of the area they might cover) layers of frozen minerals trapped within the Martian regolith. They were first noted in detail during the NASA InSight lander mission (operational on the surface of Mars between November 2018 and December 2022), significantly impacting the effectiveness of the lander’s HP3 science instrument, which included a tethered “mole” designed to burrow down into the Martian regolith. However, the “mole” kept encountering duricrust layers which, as it broke through, would surround its pencil-like body with a cushion of very loose, fine material which completely absorbed the spring-loaded action of its burrowing mechanism, preventing it from driving itself forward.

In their tests, Pavlov and his team found that the perchlorate duricrust formed in their tests would not only spread across a sample container, it was very effective in trapping neon gas (their methane analogue). Further, when the samples were exposed to the kind of natural expansion and contraction regolith on Mars would experience during a day / night cycle, they found the gas could indeed escape through cracks in the duricrust into the chamber’s atmosphere and be detected – just as with the methane around Curiosity. They also found that if a sample were subject to a pressure analogous to that of the wheel of a 1-tonne rover passing over it, it could be crushed and allow a sudden concentrated venting of any gas under it – again in the manner Curiosity has sometimes encountered.

Whether or not this is what is happening in Gale Crater, however, is open to question – as Pavlov notes. Firm conclusions cannot be drawn from his team’s work simply because scientist have no idea how much methane might actually be trapped within Gale Crater’s regolith, or whether it is being renewed by some source. As already noted, Curiosity is ill-quipped to study methane concentrations in the regolith and rock samples it gathers, because when the one instrument which could do so – the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument – was designed, it was believed any methane trapped within Mars would be so deep as to be beyond the rover’s reach, and it thus wasn’t considered as something that would require analysis. While SAM can be configured for the work, it takes considerable time and effort to do so – and that is time and effort taken away from its primary science work, which is more-or-less constant as it handles both rock and atmospheric samples gathered by the rover.

Even so, the Goddard work is compelling for a number of reasons; it points to the fact that howsoever any methane within Gale Crater might be produced (organically or minerally), there is a good chance it is becoming mostly trapped within the regolith, and possibly in concentrated pockets. If this can be shown to be the case, and if these pockets could be localised and reached by a future mission, they might some day give up the secret to their formation – including the potential they are the result of colonies of tiny Martian microbes munching and farting (so so speak!).

Starliner CFT Delayed – Twice More

The first crewed flight test of the issue-prone Boeing CST-100 Starliner capsule has been further delayed.

As I reported in my previous Space Sunday update, the vehicle had to be rolled off the pad on May 8th to fix a problem with valves on the Centaur upper stage of the launch vehicle. As a result, the launch was reset for May 17th lift-off. However, whilst the work on the Centaur stage was successfully completed, a helium leak was discovered within the Service Module responsible for supplying power and propulsion to the Starliner capsule when in orbit.

The leak was small but significant; the service module has four “doghouse” thrusters assembles mounted on it, these contain thrusters which are used to manoeuvre the vehicle in space and used hypergolics – propellants which spontaneously combust on contact. These are common practice in spacecraft, but in Starliner’s case, helium is used to both help “push” the propellants into the thruster combustion chambers and flush the chambers between firings in order to avoid premature combustion the next time the thrusters are used, causing a sudden loss of vehicle control. Ergo, not having a helium leak is a good idea.

The leak was detected on May 15th, and the launch initially moved back from May 17th to May 21st so it could be dealt with. But on May 17th, further tests were carried out which revealed the issue had not been completely resolved. As a result, NASA indicated the launch will now proceed no earlier than Saturday, May 25th, to allow repairs to be completed and the system checked prior to rolling the vehicle and its launcher back to the pad a Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

Mercury’s BepiColumbo Mission Angst

Launched in October 2018 (see: BepiColombo and giant planets), the joint European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) mission to Mercury, BepiColombo, is causing some anxiety among the mission managers and engineers.

As I noted in covering the launch, getting to the inner planets of the solar system is as hard – if not harder – than getting to the outer planets with our currently technology. In BepiColumbo’s case more energy has to be imparted to the vehicle to reach its target than NASA’s New Horizons space vehicle required to reach and fly past (2015) Pluto; in fact, and in terms of thrust, the vehicle is equipped with the most powerful ion propulsion system yet flown in space.

This propulsion system performs two roles: it helps accelerate the craft as it performs the necessary fly-bys of Earth (1), Venus (2) and Mercury (6 – with three remaining in September and December 2024, and one in January 2025) in order to reach a point where it can enter orbit around Mercury (in December 2025), and to act as a low-thrust, long-duration brake to slow the vehicle in its final months of flight (mid-to-late 2025) so that it can be captured by Mercury’s weak gravity.

In addition, the thruster system is required for a series of “mid-course” corrections designed to keep the vehicle on track while en-route to Mercury and to counter the gravitational influences of the planets as it flies past them and that of the Sun. One of these corrections took place on April 26th, 2024 – but the Mercury Transfer Module (MTM), the power and propulsion unit on the spacecraft, failed to deliver 100% of the electrical power required for the manoeuvre.

This prompted engineers to start investigating the issue and try to ensure adequate power was being routed to the propulsion system. By May 7th, they had managed to bring the available power for the propulsion system up to 90% of its full requirement – but as of the time of writing, have been unable to restore the full requirement needed by the ion thrusters.

However, the mission is not currently in any immediate danger- 90% of thrust was sufficient for the mission team to order an additional mid-course correction to get the spacecraft back on track for its September 2024 fly-by of Mercury. It is entirely possible that if the issue cannot be fully resolved, and propellant reserves allowing, additional corrective burns can be added to the mission to help keep the spacecraft on course during its final fly-bys of Mercury, with a longer braking burning then being used to get the vehicle into orbit.

The overall goal of the mission is to carry out the most comprehensive study of Mercury to date, examining its magnetic field, magnetosphere, interior structure and surface. In addition, during the flight, BepiColombo will make the most precise measurements of the orbits of the Earth and Mercury around the Sun made to date as a part of further investigations of Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Once in orbit, the vehicle will split into two separate units: the 1.1 tonne, ESA-built, Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) will remain attached to the MTM for powering its 11-instrument science payload. The smaller (285 kg), spin-stabilised (meaning that prior to detaching from MPO, it will be set spinning at 15 rpm so it can remain stable) JAXA-built Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO, also called Mio) will separate so that it can enter a polar orbit over Mercury. Both craft will have a primary orbital mission around the planet of one terrestrial year.