The first all-European crewed space mission is currently underway at the International Space Station (ISS) – albeit through the auspices of two US-based companies and NASA.

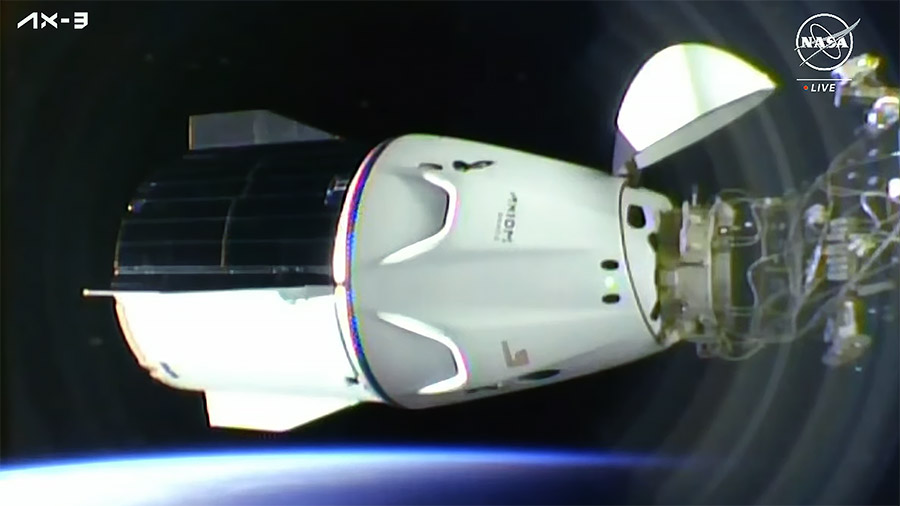

The Axiom AX-3 mission lifted-off from Launch complex 39A at Kennedy Space Centre, Florida at 21:49 UTC on January 18th, carrying a crew of four aboard the Crew Dragon Freedom. As its name suggests, the mission is the third crewed flight to the ISS undertaken on a private basis by Axiom Space, utilising the launch capabilities of the SpaceX Falcon 9 booster and Crew Dragon capsule.

Delayed by 24 hours to allow for additional pre-flight checks, the launch was perfect, carrying mission commander and former NASA astronaut Michael López-Alegría, representing Spain, his nation of birth (he holds dual Spanish and American citizenry), vehicle pilot Walter Villadei of the Italian Air Force, making his first fully orbital flight into space, having previously flown as a member of Italy’s sub-orbital flight with Virgin Galactic, and mission specialists Marcus Wandt, a reservist in the European Astronaut Corps, and Turk Alper Gezeravcı who becomes his country’s first astronaut.

Following launch, the Falcon 9’s first stage made a successful landing at Cape Canaveral Space Force Base south of Kennedy Space Centre, whilst the dragon went on to a successful orbital insertion and separation from the booster’s upper stage, to start a 36-hour gentle rendezvous with the ISS, the Crew Dragon gently raising its orbital altitude to match that of the ISS before closing to dock with the station.

The latter took place at 10:42 UTC on Saturday, January 20th, 2024, when Freedom latched on to the forward docking port on the station’s Harmony module and pulled into for a hard dock. 90 minutes later, with post-flight checks completed and the AX-3 crew able to change from their pressure suits to less restrictive flight wear, the hatches between station and capsule were opened, and López-Alegría led his crew out to be greeted 7 members of ISS Expedition 70.

The mission – which is due to last some 14 days at the station – marks the sixth orbital flight for López-Alegría. He first flew in 1995 on the second mission of the US microgravity laboratory, a research module carried within the payload bay of the space shuttle prior to the development of the ISS. He subsequently flew on STS-92 and STS-113 whilst the ISS was being constructed, prior to serving as ISS mission commander for the Expedition 14 rotation in 2006-2007. He also served as the head of NASA’s ISS Crew Operations office (1995-2000) and is also a former NASA aquanaut, serving on the first NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO) crew aboard the Aquarius underwater laboratory, in October 2001. Having joined Axiom in 2017, he first flew aboard Crew Dragon in the AX-1 mission in April 2022.

The remaining three AX-3 crew are all orbital rookies making their first stay in space. However, their presence on the ISS means that the station now has its largest ever international crew, with two US citizens, three Russians, a Dane, and a Japanese astronaut making up the ISS expedition crew.

We’ve got so many nationalities represented on board, and this is really symbolic of what we’re trying to do to open it up not only to other nations, also to individuals to researchers to continue the great work that’s been going on onboard the ISS for the last two decades plus.

– Michael López-Alegría

While aboard, Ax-3 crewmembers will live and work alongside the station’s current residents, performing experiments and research started with the first two Axiom missions, with a focus on human spaceflight and habitability in microgravity environments, a goal very much in keeping with international research on the station and of particular interest to Axiom Space, which plans to operate its own orbital facilities, initially docked their own modules with the ISS prior to separating them to become a dedicated orbital facility when the ISS is decommissioned in 2030.

In addition, the AX-3 crew will conduct research into AI and human health – the mission includes an experiment from Turkey called Vokalkord, which uses AI algorithms to diagnose several dozen diseases by analysing a cough or someone’s speech -; experiments with high-strength alloys, with implications for in-space construction and assemblies as well as other biology and physics-related work.

China’s SpaceX? Sort-of, But Not Exactly

A glance at the image above might initially suggest it is one from the history books: an early flight test of the Falcon 9 reusable first stage out of SpaceX’s flight test centre at McGregor, Texas. However, the landscape isn’t entirely in keeping with that of McLennan and Coryell counties, Texas, whilst a closer look at the booster might reveal something of the truth, thanks to the large red flag painted thereon.

The craft is in fact the Zhuque-3 vertical take-off, vertical landing unit 1 (VTVL-1), a test article developed by Chinese private sector launch start-up Landspace. It is intended to pave the way for a semi-reusable launch vehicle called Zhuque-3 (“Vermillion bird-3”), which is intended to have the same overall launch capabilities as Falcon 9 (up to some 21 tonnes to low-Earth orbit (LEO) when flown fully expendable, and between 12.5 and 18.4 tonnes when the first stage is to be re-used). However, to call it an outright “Falcon 9 clone”, or a “copy” of SpaceX’s work would not be strictly accurate.

Whilst there is much about Falcon 9 which likely influenced the Zhuque-3 design, the fact is that its looks are as much about the old axiom, form follows function, as much as any “copying” of SpaceX; the overall design and appearance of the booster and its landing legs are simply the result of their form being the most logical to meet the requirements of their functionality (hence why, in aircraft design, for example, vehicles designed for a specific task by different nations can often end up appearing quite similar, even if not direct copies).

Similarly, and while SpaceX fans have pointed to Landspace also “copying “SpaceX in the use of stainless steel for the rocket and the use of methlox – liquid methane/liquid oxygen – engines (all of which are used by SpaceX in their Starship / Super Heavy combination), the fact is that the Chinese commercial space sector has been dabbling in methlox propellants since around 2015, pre-dated Starship development, whilst the use of stainless steel in the Zhuque-3 rocket is perhaps more the result of Landspace already having experience in fabricating rocket cores out of it via their operational Zheque-2 launch vehicle than any attempt to copy someone else’s work. While also is not to say that SpaceX haven’t cut a path that other companies around the world can follow.

The first (expendable) launch of Zhuque-3 is expected in 2025, and will mark a further expansion of China’s commercial space sector, in which Landspace is just one of a number of companies developing or operating launch systems and developing semi-reusable launchers. Just how much competition there is already in the market is perhaps illustrated by the fact that some news agencies reported on the Zhuque-3 test flight by using video footage of the second test carried out by China’s iSpace company of their Hyperbola-2 VTVL test vehicle, which took place in December 2023!

Such is the broad and rapid pace of reusable booter development in China’s commercial space sector, footage similar to this video showing the first VTVL test of the iSpace Hyperbola-2 booster VTVL test article (and which I covered at the time), was mistakenly used by some news outlets to report on the January 19th Zhuque-3 VTVL test. Video credit: iSpace via SciNews

Overall, the Chinese commercial market is as richly diverse as the developing commercial space sector in the US, and with China enjoying good trade relations with a number of Asian countries looking to develop space-based capabilities, there is good potentially for interest in using these vehicles to gain something of an international footprint.

Three Mini Mission Updates

Peregrine Mission One

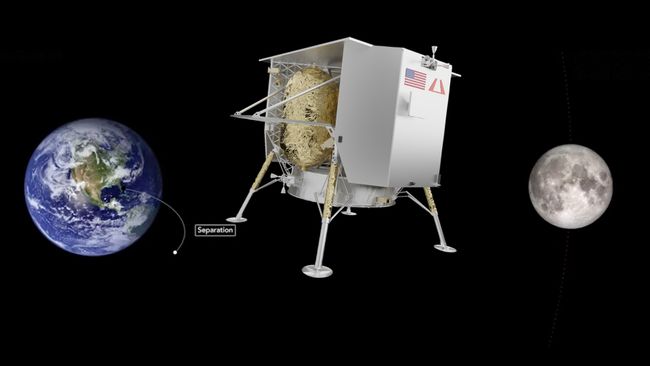

Astrobotic’s Peregrine Mission One (aka Peregrine or Peregrine One), is now officially over. As I’ve previously reported, the NASA-funded private mission to put a lander on the surface of the Moon under the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, got off to a flying start with a January 8th, 2024 ride to TLI (trans-lunar injection) aboard the maiden flight of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket. However, some time after the separation of the lander from the rocket’s Centaur upper stage, a propellant leak occurred which resulted in the lander entering an uncontrolled tumble, shifting it away from its rendezvous with the Moon and starving it of the propellants needed to make a landing even if it could get there.

On January 14th, the lander crossed the orbital path of the Moon, and shortly after that, gravity took over and started pulling it back towards Earth. As a result, on January 18th, 2024, the craft re-entered the atmosphere over the South Pacific, where it proceeded to burn-up. However, analysis of data returned by the craft as it headed back to Earth revealed a possible cause of the propellant system failure, as related by Astrobotic CEO John Thornton during a press briefing on January 18th:

The valve separating the helium and oxidiser in the lander’s propulsion system did not re-seal properly. This allowed a rush of helium to enter the oxidiser tank, raising the pressure to the point where the tank ruptured.

This knowledge actually helped in securing the lander’s final demise: by characterising the nature and direction of the leak, together with the rate of loss of remaining gases, flight engineers were able to put the lander into a more controlled entry into the atmosphere, pushing itself farther over the South Pacific to avoid the risk of any components surviving re-entry from falling over land masses.

Despite the loss, Astrobotic remain upbeat about their next lunar mission – again supported by NASA – which will hopefully see the company’s Griffin lander deliver NASA’s VIPER rover to the Moon in 2024.

Japan’s “Sniper” Achieves Lunar Landing But Not Without Issues

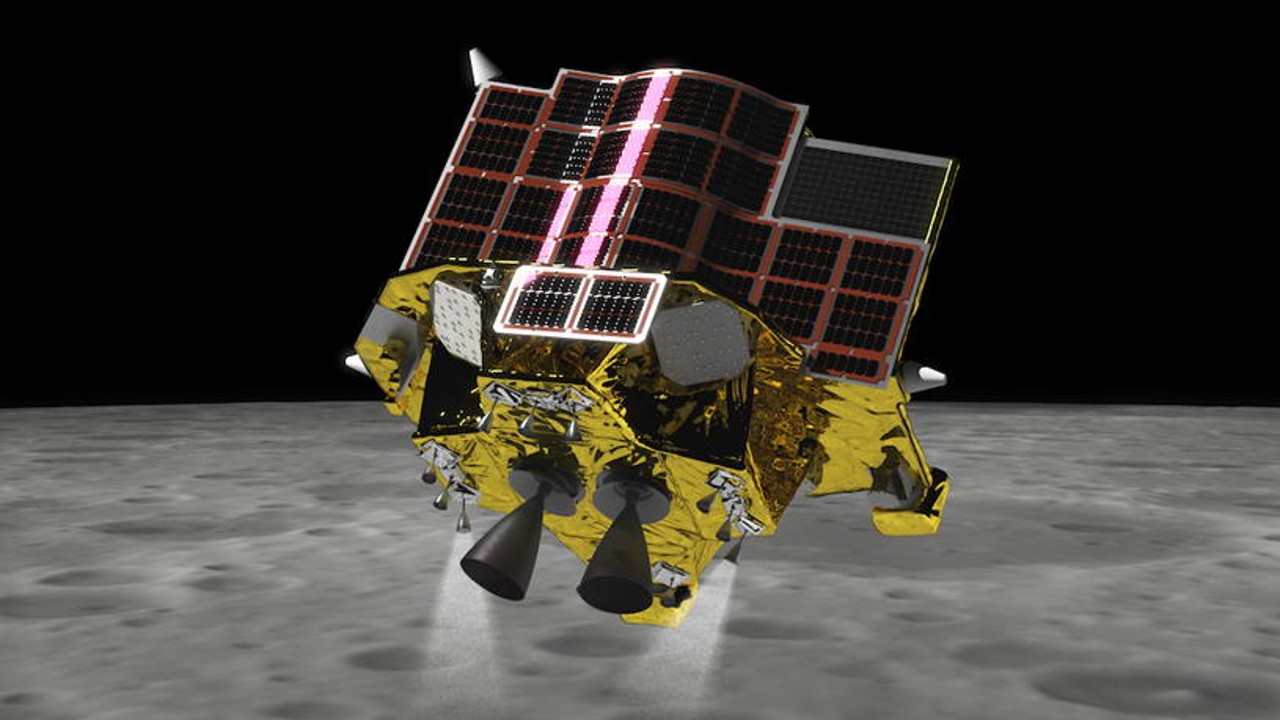

Meanwhile, Japan became the 5th country to successfully land a spacecraft on the Moon when their Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) touched-down near Shoji Crater close the Moon’s equator at 15:20 UTC on January 19th, 2024 (00:20 on January 20th, Tokyo time).

Launched in September 2023 alongside Japan’s X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM), SLIM – nicknamed “Moon Sniper” – took a leisurely trip to the Moon, spiralling slowly away from Earth to enter lunar orbit on Christmas Day 2023, orbiting the Moon at an altitude of just under 600 km. The orbit was then eased down to around 50 km, and than further reduced to a point just 20 km above the lunar surface, where the descent proper began, curving the lander in towards its target zone. At 5 km above the Moon, the descent became vertical, with livestream telemetry showing everything to be spot-on.

At 50 metres above the surface, the vehicle translated in flight, moving horizontally to position itself directly over a pre-planned landing point, before descending to a successful soft-landing. It was this final manoeuvre which formed one of the key goals for the mission. Usually, landing zones for robot vehicles are planned well in advance and encompass elliptical areas around 10 km wide and a couple of dozen in length. However, SLIM carried modified facial recognition software which allowing it to monitor its descent and adjust its position autonomously by matching surface features scanned by its cameras with high-resolution images of the landing site stored in its navigation system. At 50 metres, the craft was able to confirm its desired landing point – an area just 100 metres across by contrast to normal landing zones and then manoeuvre itself to a landing with it.

But while the landing was successful, it became clear something was wrong; there was no sign that the battery system powering the craft was receiving energy from the lander’s solar array. After investigating the issue for a number of hours, engineers at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) concluded that while SLIM had landed within the desired zone, for some reason its wasn’t correctly oriented for its solar array to receive sunlight, leaving it trapped on battery power, which would expire within hours.

Prior to completely exhausting the battery, attempts were made to put the lander in a dormant mode, the hope being that as the Moon moves in its orbit over the next few days, sunlight will fall onto the lander’s solar array, and power will start to be generated, allowing to to wake itself up and start surface operations.

While both of the mini-rovers – LEV-1 and LEV-2 are thought to have successfully reached the surface of the Moon, at the time of writing, their status is unknown.

Even if the lander cannot recover itself with the aid of sunlight, SLIM is a very successful mission: demonstrating the means to make landings on other bodies with near pinpoint accuracy will be of vital importance in unfolding efforts to explore and develop the Moon and to further explore Mars both robotically and (eventually) with human missions.

Ingenuity Suffers Communications Glitch

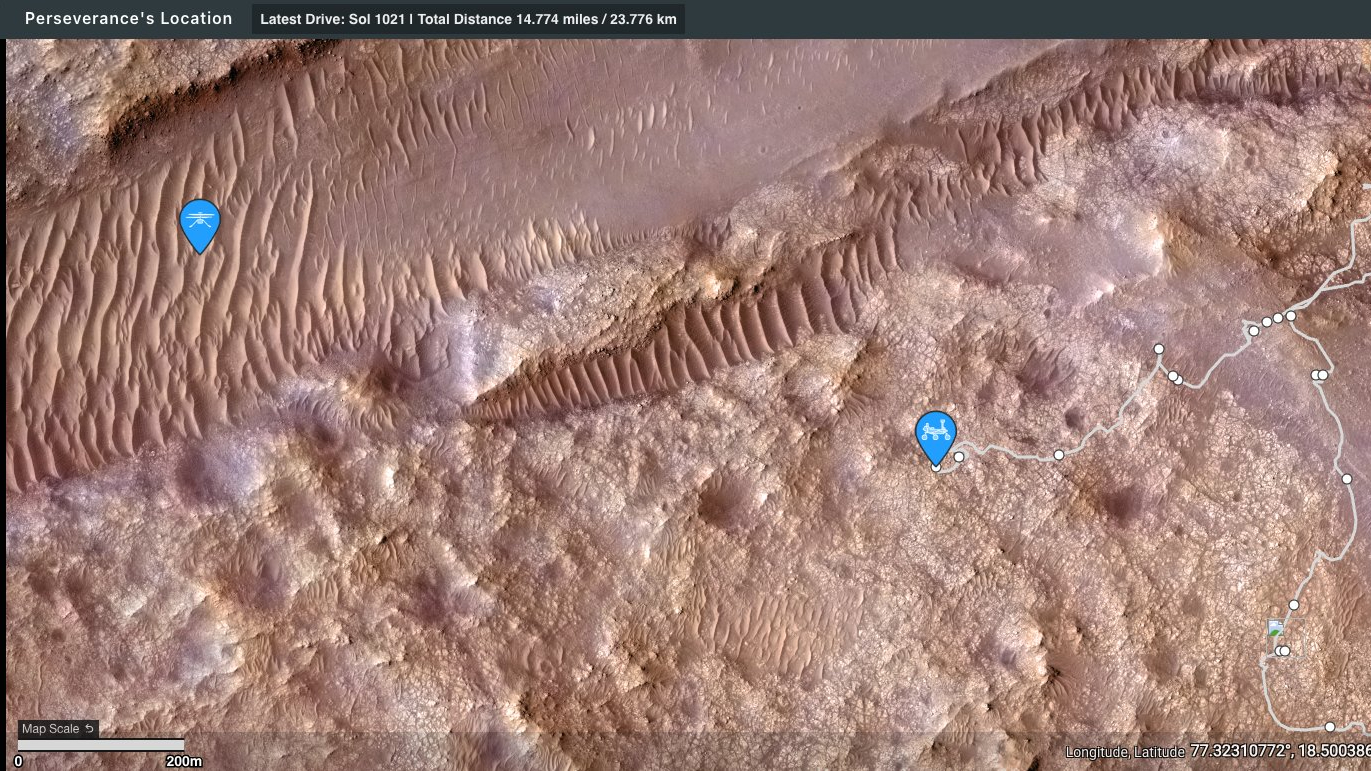

NASA’s Mars Helicopter Ingenuity completed its 72nd flight on January 18th, 2024, but not without incident. Lifting-off from sand dunes some 800-900 metres from the Mars 2020 rover Perseverance, the helicopter was engaged in a brief “pop-up” test flight intended to see it climb vertically to 12 metres altitude, hover, and then descend back to a landing.

Telemetry received via the rover indicated that the first elements of the flight were successful – but all contact was lost during the descent phase. For a time it was unclear if the use was a communications drop-out, or something more drastic, and with Perseverance out of direct line-of-sight with the helicopter, determining which was initially difficult.

In recent flights Ingenuity has been ranging ahead of the rover, acting as an airborne scout for possible driving routes. At the end of its 71st flight, the helicopter suffered a slight issue, causing a premature landing somewhat further than planned from the rover; as a result this flight was to confirm all flight systems and software were operating nominally, prior to resuming normal operations and allowing the helicopter to come back closer to the rover.

Following the loss of signal, telemetry was reviewed to see if it revealed any indication of a serious issue and possible vehicle loss. None was found, so engineers determined it was likely a comms problem and ordered Perseverance to change its communications parameters and lengthen the time periods it listens for Ingenuity’s transmissions.

As a result, in the early hours of January 21st (UTC), communications were once again established, allowing more data on the final phase of the flight to be relayed to Earth for study. Currently, Ingenuity remains grounded, and mission planners are considering ordering Perseverance to drive a point where it can see Ingenuity to allow for a visual inspection of the helicopter.