On Monday January 8th, 2024 United Launch Alliance completed the maiden launch of their Vulcan Centaur rocket with complete success, silencing critics and demonstrating that the caution and most recent delays around the launch (outside of those coming from the payload side) were worth it.

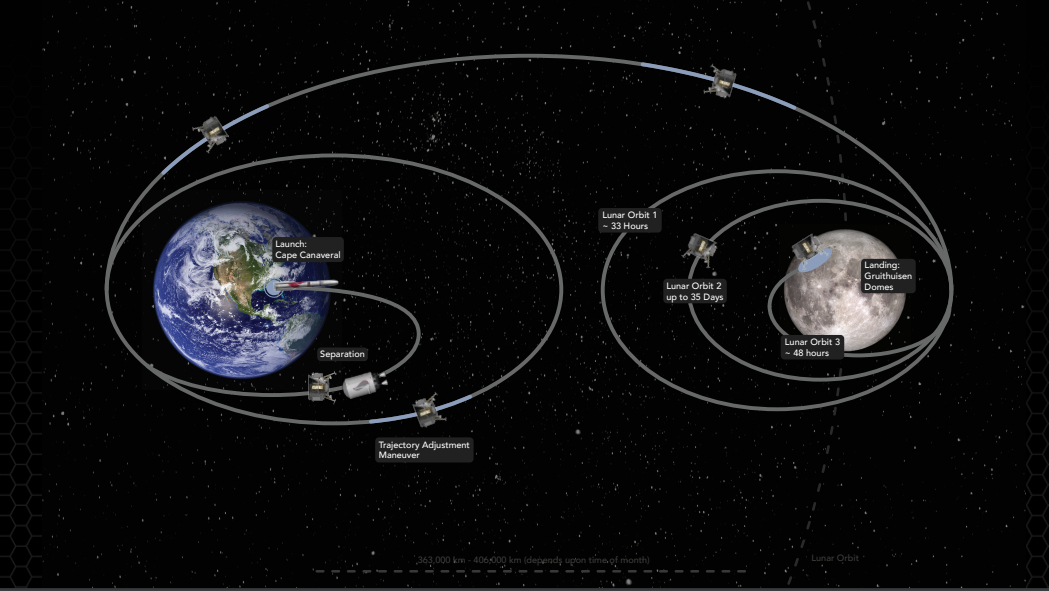

Lift-off came at 07:18 UTC as the two Blue Origin BE-4 motors of the 62-metre tall vehicle’s core stage ignited together with the two solid rocket boosters strapped on either side of it, lighting up the sky at Cape Canaveral Space Force station as the rocket climbed into a pitch-black sky. At 2 minutes into the flight, their job done, the solid rocket boosters shutdown and separated, leaving the rocket’s core to continue to power it upwards for a further three minutes before its liquid propellants were expended, and it separated to fall back into the Atlantic Ocean. The Centaur upper stage coasted for some 15 seconds before igniting it own pair of RL-10 motors in the first of three burns to place the vehicle and its payload into a trans-lunar injection (TLI) orbit and the first phase of what was hoped would be a looping trip to the lunar surface.

As I’ve previously noted, Vulcan Centaur is slated to replace ULA’s Atlas and Delta workhorses as a highly-capable, multi-mission mode payload launch vehicle in both the medium and heavy lift market places. Initially fully expendable, the vehicle may evolve into a semi-reusable form in the future, ULA having designed it such that the engine module of the core stage could in theory be recovered. It is also intended to become a human-rated launch vehicle. The Centaur upper stage is also designed with enhancement in mind, with ULA indicating that future variants might be capable of orbiting on an automated basis as space tugs or similar, once in orbit.

Whilst the vehicle carried a critical payload, the flight was actually regarded as a certification flight rather than an operational launch; one designed to gather critical performance and other data on the rocket which can be feed back into any improvements which might be required to make the vehicle even more efficient, etc.

A second certification flight is due to take place in April 2024, again with a critical payload – this one in the form of Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser cargo vehicle Tenacity, the first in a number of these fully reusable spacecraft which will help to keep the International Space Station (ISS) supplied with consumables and equipment, as well as helping in the removal of garbage from the station and the return of instruments and experiments to Earth.

While the launch of the Vulcan Centaur was a complete success – doing much too potentially boost ULA’s position as it seeks a buyer – the same cannot be said for its primary payload, which now looks set to make an unwanted return to Earth.

Peregrine Mission One (or simply Peregrine One), was to have been America’s first mission to land on the surface of the Moon since Apollo 17 in 1972. Financed in a large part via NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, this mission is nevertheless regarded as a private lunar mission, carrying some 20 experiments and instruments allowing it to operate in support of NASA’s broader lunar goals.

At first everything seemed to be going well with the mission. The lander rode the Vulcan Centaur to orbit before it powered-up its own flight systems and ‘phoned home to say it was in good shape. Then, some 50 minutes after launch, and the Centaur upper stage having completed its final burn to set the lander on its looping course to the Moon, Peregrine One separated from its carrier.

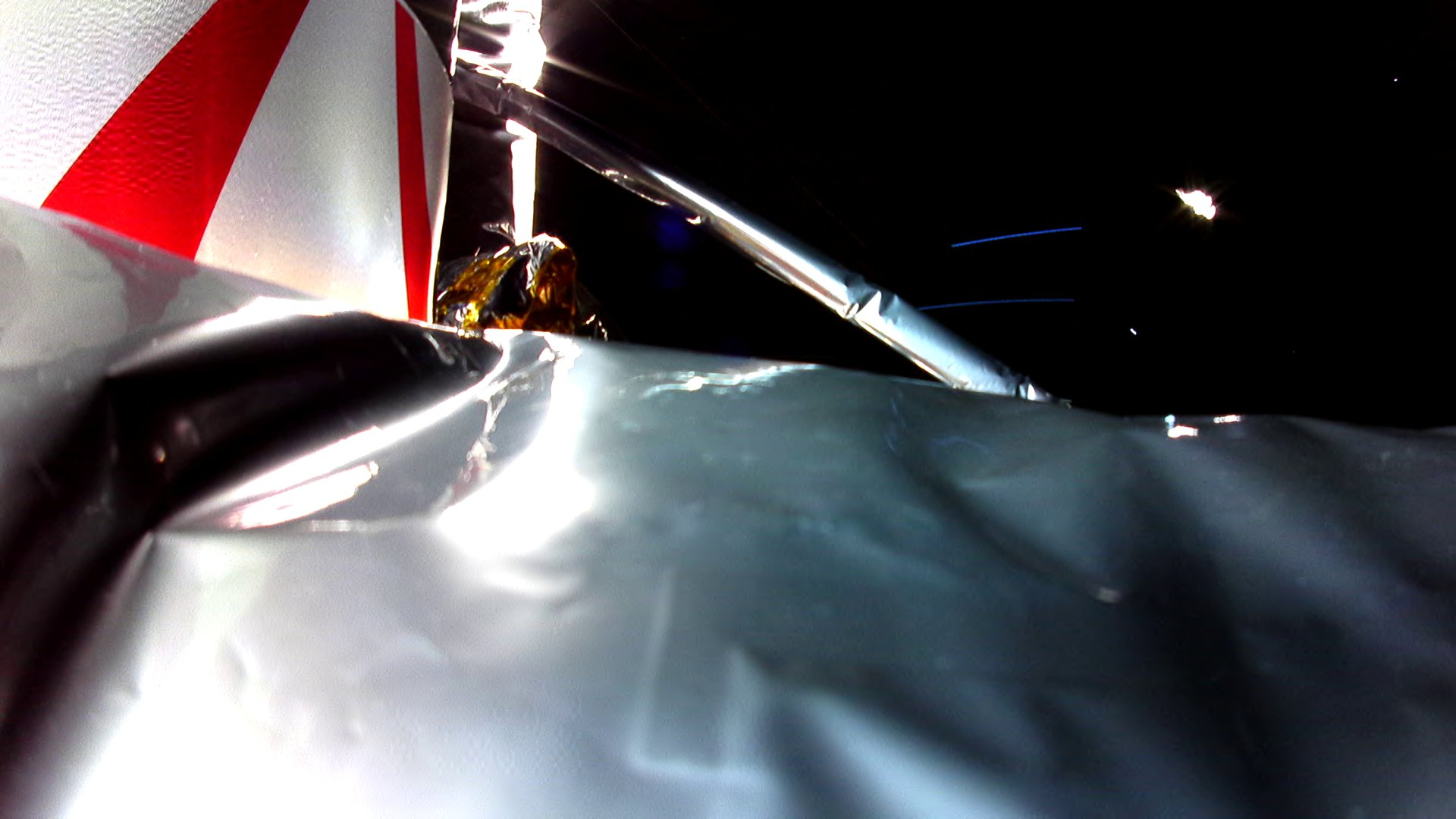

All appeared to go well in the hours immediately following separation, but following an attitude adjustment, telemetry started being received suggesting the craft was in difficulties and was unable to correctly orient itself. It was not initially clear what was wrong with the lander, and in an attempt to find out, Astrobotic – the company responsible for designing and building it – ordered camera mounted on the lander’s exterior to image its outer surfaces for signs of damage. The very first image returned showed an area of the craft’s insulation around the propulsion system – required to make the descent and soft-landing on the Moon – had suffered extensive damage, with propellants leaking into space from around it.

This, coupled with the telemetry gathered from the lander caused Astrobotic to determine that one of the vehicle’s attitude control system (ACS) thrusters was still firing well beyond expected limits, most likely due to a failed / stuck valve, placing the vehicle in an uncontrollable tumble.

If the thrusters can continue to operate, we believe the spacecraft could continue in a stable sun-pointing state for approximately 40 hours, based on current fuel consumption. At this time, the goal is to get Peregrine as close to lunar distance as we can before it loses the ability to maintain its sun-pointing position and subsequently loses power.

– Astrobotic statement, Monday, January 8th

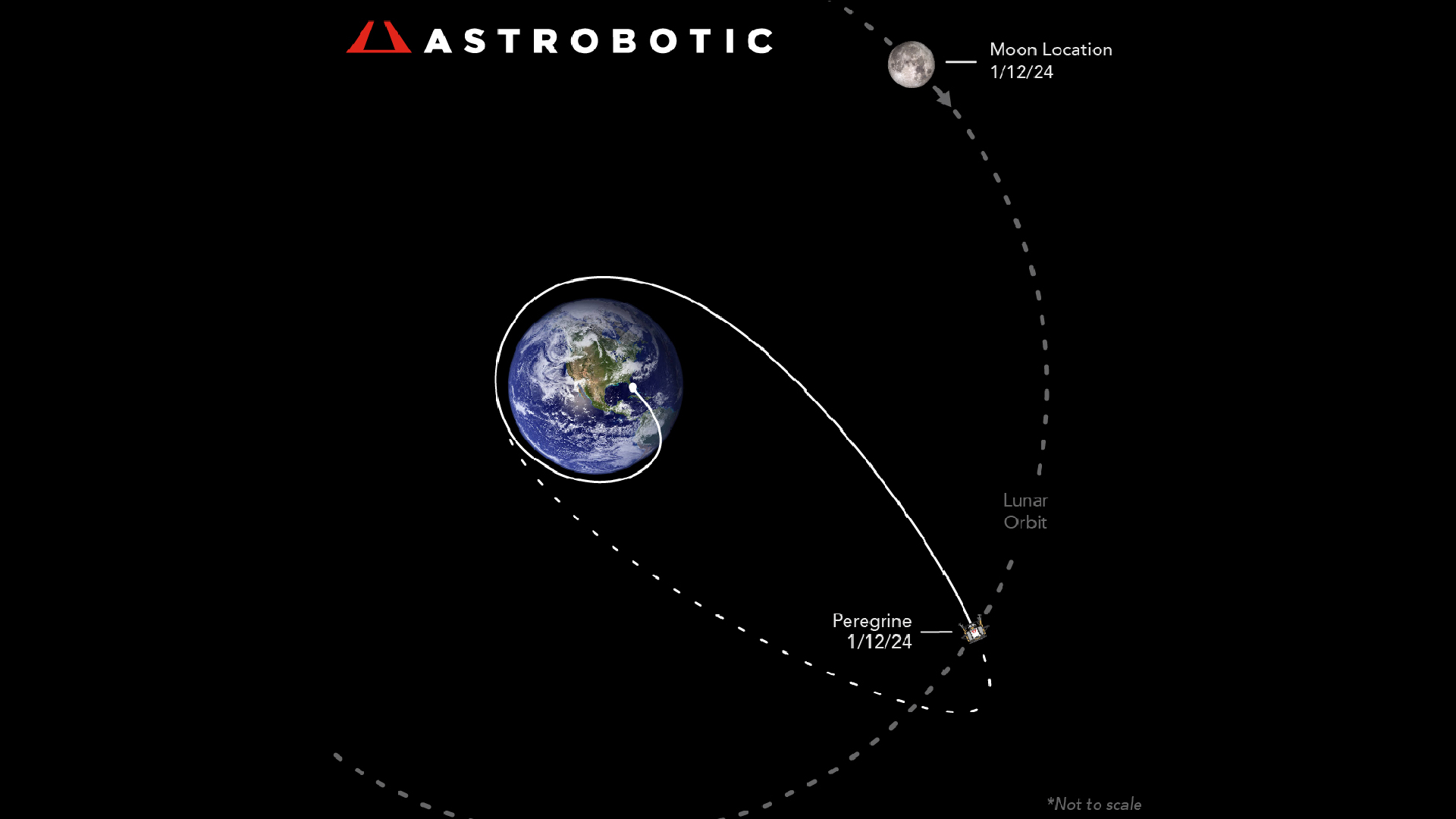

Initially, it had been hoped that the craft would still reach the Moon and make what is euphemistically called a “hard landing” (that is, crash into it) around the time of the planned landing date of February 23rd, engineers having calculated that by then, even if the rete of propellant loss slowed over several days and ceased, the craft would have insufficient reserves to make a controlled landing. However, by mid-week it was clear even this would not be the case; the leak had put Peregrine One on a much more direct path towards the Moon’s orbit than had been intended such that on January 12th, an status update from the company noted:

Peregrine remains operational about 238,000 miles from Earth, which means we have reached lunar distance! Unfortunately, the Moon is not where the spacecraft is now, as our original trajectory had us reaching this point 15 days after launch, when the Moon would have been at the same place.

– Astrobotic statement, Friday, January 12th

However, the one “good” piece of news through the week was that as time progressed, the propellant leak deceased, and some steps to help stabilise the vehicle – and maintain its orientation to the Sun such that its solar arrays could continue to received energy and power the vehicle’s systems – could be taken. These in turn allowed a number of the experiments on the lander to be powered-up. While they are not operating in their intended modes (or location), it is hoped that they will still be able to gather data on the radiation environment in interplanetary space around the Earth and the Moon.

The most recent projections from Astrobotic (January 14th) suggest that as the Lander has in sufficient velocity to complete escape Earth’s gravity well, it will likely start to “fall back” to Earth in the coming weeks, and orbital mechanics being what they area, most probably slam into the upper atmosphere and burn-up.

Given Peregrine One’s involvement in the CLPS programme, NASA has been monitoring the Peregrine One situation closely, and on January 18th the agency and Astrobotic are due to convene a telecon in order to review Astrobotic’s efforts to recover the craft and what they have learned. In the meantime, agency officials have noted that the failure of Peregrine One to successfully achieve a lunar landing will not in any way impact CLPS.

Artemis 2 and 3 Slip

On January 9th, 2024, NASA announced America’s return to the Moon with crewed missions at the head of Project Artemis is to be further delayed.

In the announcement, made in part by NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, it was indicated that the upcoming Artemis 2 mission around the Moon and back, and intended to take place in November 2024, will now not take place before September 2025. Meanwhile, the first US crewed mission to the surface of the Moon will now occur no sooner than September 2026.

The reasons given for the delays relate most directly to Artemis 2. In particular, there are a number of new systems and capabilities in development as a part of the overall Artemis programme which are now far enough along that it makes sense to delay Artemis 2 to leverage them, as they offer increased safety at the pad and prior to launch – such as improved means for crew egress from the launch vehicle in an emergency, and faster propellant loading capabilities.

Another cause for the delay is on-going concerns about the performance of the ablative heat shield on the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MCPV). Whiles the shield did its job and protected the unscrewed capsule of Artemis 1 during its passage back into the Earth’s atmosphere at the end of that mission in November 2022, it still showed signs that rather than charring in place, some of the material actually peeled away from the vehicle as it charred, which is not supposed to happen.

Finally, concerns have recently been raised about the electrical system managing the crew abort system rockets, designed to haul the Orion capsule and its crew clear of the SLS rocket if the latter suffers a serious failure during the initial ascent to orbit. As a result, further tests have been requested on that system.

I want to emphasize that safety is our number one priority. And as we prepare to send our friends and colleagues on this mission, we’re committed to launching as safely as possible. And we will launch, when we’re ready.

– Jim Free, NASA’s Associate Administrator

The announcement was, oddly, seen as a cause for vindication among some SpaceX fans – the private launch company has been cited as a potential reason for delaying the Artemis 3 programme, given they are still a long way from demonstrating they have the ability to supply NASA with an operational lunar landing vehicle and the means to get it to lunar orbit.

However, even the addition of a further 11 months to the Artemis schedule still leaves SpaceX with precious little time to achieve those goals in a manner which meets NASA’s safety requirements. As such, the concerns about SpaceX being able to meet current Artemis time faces, as highlighted (again) in 2023 by the US Government Accountability Office (which has an uncannily accurate eye for predicting programme slippages and their causes) still remain valid.

Of Strings and Rings

The Standard Model of cosmology, also known as the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (shortened to Lambda-CDM or ΛCDM) model, is the mathematical model of the Big Bang theory – the most accepted theory explaining the creation and continued expansion of the universe (and its potential demise). It has a lot going for it, in that much of what we observe in the universe around us tends to conform to it, and other cosmological theories and laws – such as the Hubble–Lemaître law – appear to be in lockstep with it.

However, it is not entirely without holes, and these appear to be on the increase, leading to the Standard Model to be increasingly challenged. In the last few years, for example, two extraordinary cosmological structures have been found, which between them offer both direct and indirect challenges to the Standard Model as we currently define / understand it.

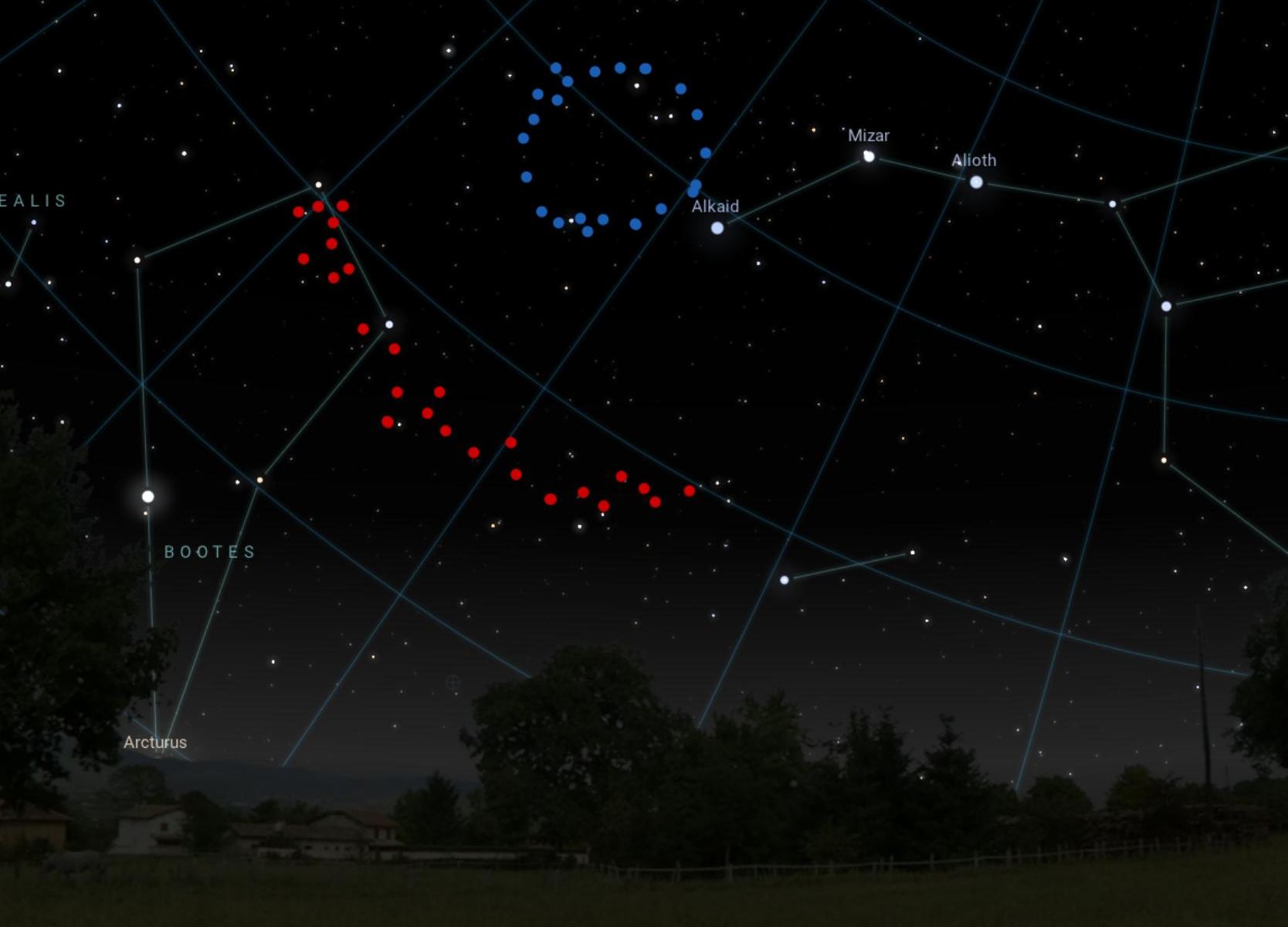

In 2021, astronomers studying other galaxies happened across a gigantic arc of galaxies 3.3 billion light years across, all of them some 9.2 billion light years from Earth and all of them existing in the same two-dimensional plane, thus confirming them as a genuine string crossing our skies close to the constellation of Boötes the Herdsman. Far too faint to see, the string was discovered accidentally, and called in typical imaginative astronomical fashion, the Great Arc.

On its own, it was unique and curious enough. Only it turns out it is not alone. In 2023, whiles studying the same region of sky on an unrelated matter, astronomers from the University of Central Lancashire have discovered a second massive structure of ancient and faint galaxies, these forming a huge ring at least 1.5 billion light years across. What’s more, analysis of various light and mineral wavelengths have again not only revealed the galaxies within it really do form a ring (and its not some line-of-sight trick), but that they are collectively the same distance from us as the Great Arc.

Which is quite a coincidence. But that’s not the really interesting thing. The really interesting thing is that according to the Standard Model, if we go back 9.2 billion years, no structure of this kind of form could exceed 1.2 billion light years across – less than both the Great Ring and the – wait for it – Big Ring (while the Standard Model does allow for some structures larger than 1.2 billion years across a) these would have originated as “bubbles” created by pressure and sound in the earliest moments of the universe, and b) would be spherical in shape, not 2-deminsional strings or rings).

Thus, both of these strange, distant artefacts must have been created by some other mechanism. This would suggest that either astronomers and astrophysicists are missing something within the Standard Model – or the universe might not conform to the Big Bang theory as closely as is believed, or possibly – if very remotely – at all.

But if not the Big Bang, then what is behind the universe? Well there are some other models out there. One of these is Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC), which has actually been undergoing something of s resurgence of study and theorising, thanks to the likes of Sir Roger Penrose. Like the Big Bang (and its associated Big Crunch), CCC postulates the universe goes through a series of unending cycles. However, whereas the Big Bang / Big Crunch requires that nothing of the previous cycle remains prior to the start of the next cycle, CCC allows for remnants of past cycles to continue to exist through- and even inform – the creation of the next cycle. Thus, it would allow for the existence of both the Great Arc and the Big Ring.

The problem here however, is that CCC explains even less about the observable universe than does the Standard Model – so no-one is serious suggesting the latter get thrown out with the bath water just yet. But, the last two decades have seen a number of holes poked into the Standard Model, and the Big Ring and Great Arc might yet prove to be another such hole. As such, they do perhaps stand as a reminder – to paraphrase the late Douglas Adams – that the cosmos is not only stranger than we imagine – it’s stranger than we can imagine.

As always, Inara, kudos for your exemplary piece on “space news”. It’s actually weird reading about these things. On one hand, we have extraordinary technology able to see so far away (and back in time!) in the Universe that it’s almost uncanny — and leads us to question everything we know, over and over again, as newer generations of telescopes and other arrays of far-reaching instrumentation gives us a wealth of new, fresh data to analyse — and possibly rethink all our theories.

But on the flip side of the coin, we observe the struggle that NASA has to go through to essentially replicate what was already done half a century ago, with roughly the same crude technology — essentially, a controlled explosion of a huge bomb placed beneath a capsule containing a handful of human beings. All of that is roughly the kind of technology we had a century ago — obviously, engineered to a different scale, but nevertheless it’s the “same old tech” in a new wrapping. And yet, all missions tend to get delayed further and further in time because of some essential item — apparently trivial but of devastating consequences if it gets ignored — fails to meet specifications, or, when it does, and put to trial, it fails unexpectedly with the worst possible consequences.

There is something fundamentally wrong with the whole approach. Aye, I’m aware that there are few environments as hostile to human life as Space, and thus the immense scale of technological difficulties to overcome to make s short trip to the Moon in 2026 slightly safer than it was in 1969 or 1972, while giving the crew a little more breathing room (literally so!) and possibly even a place where they can stretch their legs.

Nevertheless, I’m still surprised at the incredibly slow pace of development.

By now, we should have advanced our materials technology to the point that we would be able to set up a space elevator to place cargo directly in orbit — something insanely expensive to build, but which would instantly pay for itself in a few years (or less). This would at least allow us to pre-build all sorts of modules, no matter what their size and weight might be, to assemble them easily in orbit, and move it around with a small but efficient ion drive (powered by a safe thermonuclear power generator). Once reaching the Moon, another space elevator (much shorter and far cheaper to build) would safely place the cargo on the Moon’s surface, and that would be it.

Ion drives could also push a relatively large structure across space until it reaches Mars and use essentially the same approach to deliver cargo there as well. In essence, all future “visits” to extraterrestrial planets (and their moons) could be accomplished using a similar approach. The space elevators would not even require human builders — just “assembly robots”, working together to place all modules in their right places with nanometer accuracy. Once a space elevator is finished on one planet or moon, the whole swarm of robots would go back to their “mothership”, move on to the next one in line, and build a new space elevator on the next — and so forth, until we manage to cover a substantial part of all visitable celestial bodies up to and including Jupiter’s orbit (or, who knows, even reaching Saturn and its intriguing collection of moons — not to mention its rings, of course).

This approach would make total sense for the 2020s and 2030s, leveraging on technology that couldn’t even be imagined a generation or two ago, much less implemented.

I mean, in 1969, the on-board computer on the Apollo 11 just had 16 Kbytes of RAM (later models had a bit more — up to 64 Kbytes I think). You could do an emulator of that software to run inside a browser with JavaScript — and still have plenty of computing power left to do so much more.

Yet, in spite of all these advances, they seem to be impossible to conciliate with contemporary rocket design and its tiringly slow pace of development. No matter how skillfully engineered, this tech continues to look outrageously outdated, clumsy, kludgy, and undeserving of the billions put into it for such poor results…

Oh well. I used to be much more optimistic in the 1980s, with the arrival of Space Shuttle and the amazing leaps in materials engineering by the end of the millennium. Alas, all that tech didn’t end up in sending humans to the stars, but rather in the pockets of the construction industry, which loved all those inventions and put them to good use,,,

LikeLiked by 1 person

We already have ion propulsion systems – although as you note, they really need nuclear power sources if they are to push large masses around the solar system. Plus, NASA / DARPA should be testing a nuclear thermal propulsion system around 2030 (if not a little sooner), and companies like Rolls Royce are working on very compact fission reactor systems for use in space for propulsion / power purposes. Obviously we have to first get them out out of Earth’s gravity well, and like it or not, chemical propulsion remains the most effective way of doing so.

The space elevator idea has been around a long time – since Tsiolkovsky, in fact – although it was another Russian in the form of Yuri N. Artsutanov who first proposed a practical, tensile-based means of building such a mechanism. The problem is that as much as might be wished and despite the amount of research being pumped into it, materials processing has not advanced to the point of producing a super-strong, super-light material which could be used to build the two 36,000 km-long structures required by an elevator (one to reach down to the surface of the Earth, the other to reach out to the counterweight required to maintain the tensile strength of the the entire structure). and able to withstand all of the forces it would face. While it has been suggested that carbon nanotubes (CNTs) might one day be capable of handling the stresses such a structure would face and be light enough to make it genuinely feasible, we’re still far short of reaching that point in their development.

However, one area where CNTs could have a significant impact is with space vehicles themselves: the use of CNTs with a crewed vehicle’s structure – say something like a Mars cycler – could not only help with the vehicle’s structural strength for comparatively less mass than other materials they could be used a shielding mechanism against galactic cosmic rays (GCRs), which are in many respects far more a threat to the health of crew in deep space than solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs), in that they cannot be easily shielded against.

LikeLiked by 1 person