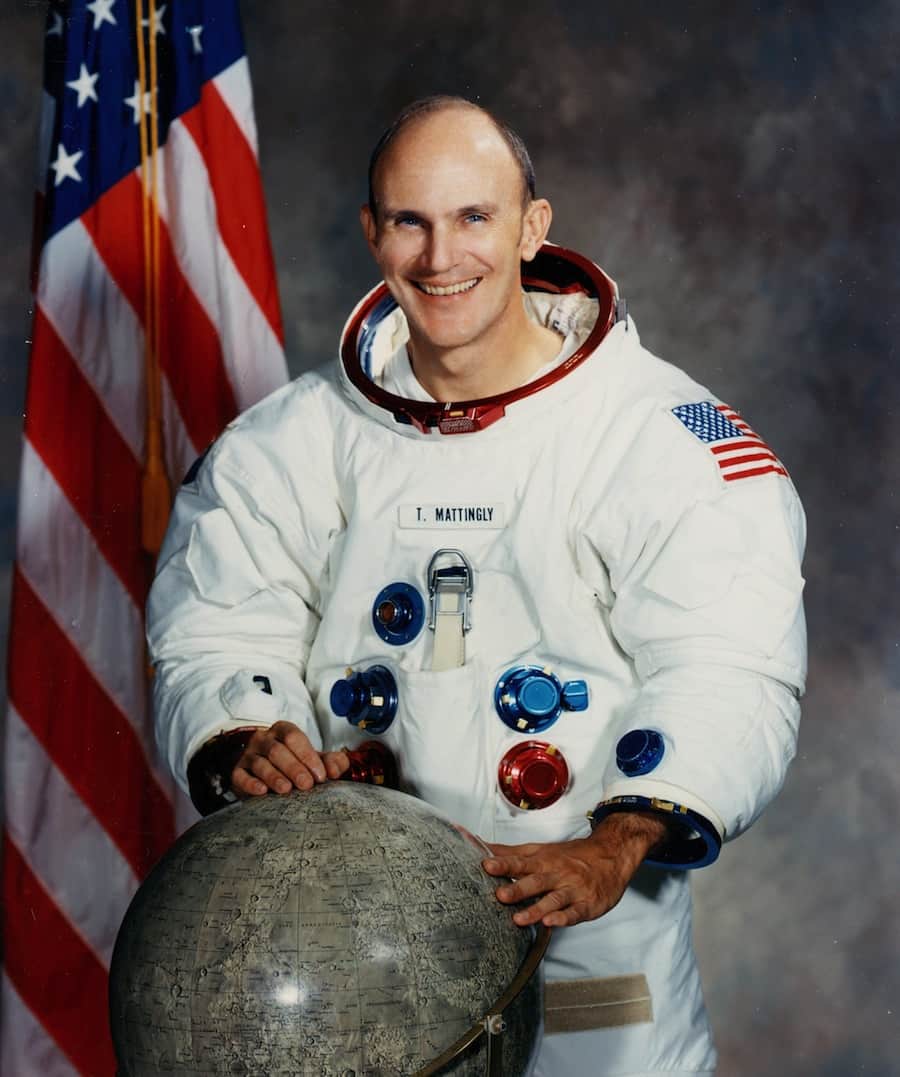

On November 3rd 2023, NASA announced that Apollo and shuttle era astronaut Thomas Kenneth “Ken” Mattingly II, had passed away on October 31st, 2023 at the age of 87.

Perhaps best known, courtesy of Ron Howard’s film and his portrayal by Gary Sinise, for the mission he never actually flew, that of Apollo 13, Mattingly did participate in the penultimate Apollo mission to the Moon – Apollo 16 – and also flew two space shuttle missions in the 1980s.

Born on March 17, 1936, in Chicago, Illinois, Mattingly grew up with aviation in his blood, his father being employed by Eastern Airlines, and came to see it as a natural choice of career, opting to study for and achieve a BSc in aeronautical engineering prior to joining the US Navy in 1958 and applying for flight school.

Graduating as an attack aircraft pilot in 1960, Mattingly served first in VA-35 based out of Virginia, with an at-sea rotation aboard the USS Saratoga. Following this he was assigned to the heavy attack / reconnaissance squadron VAH-11 with his rotations split between the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt and Naval Air Station Sanford, Florida. It was whilst at the latter that Mattingly accepted an invitation to share a flight an a fellow aviator in his squadron had been ordered to take in order to gather aerial photographs of the launch of Gemini 3 out of Cape Canaveral in March 1965.

Shortly after this, and having being refused admission into the Navy’s Test Pilot School due to his assignment at VAH-11 finishing after the class of ’65 had commenced, he accepted a slot with the US Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School. While primarily a USAF school, this also took on pilots from both the Navy and the civilian sector for courses, and in joining, Mattingly found himself training alongside future astronauts “Ed” Mitchell and Karol Bobko whilst receiving instruction under future astronauts Charles Duke and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield Jr.

All of this had an impact on Mattingly, who applied for and was accepted into the NASA Group 5 astronaut intake of 1966. Coincidentally, his final selection interview was chaired by John W. “Jim” Young – one of the crew of the Gemini 3 mission he had watched launch whilst riding the photographic mission – and Michael Collins. It was an event he didn’t feel he’d fared well at, thinking he annoyed Collins and felt “perplexed” by Young’s attitude.

Following initial training, Mattingly was selected as part of the back-up crew for Apollo 8 and served as CapCom (capsule communicator – the individual charged with communicating directly with a crew in space) for that mission. He then worked with Michael Collins during the training cycle for Apollo 11, having being assigned as Collins’ “second” back-up after Bill Anders. As there was a risk that the mission could slip from July 1969 and into August – and Anders would be leaving NASA during that month – Mattingly was put on the back-up roster and training in case the mission did slip beyond Anders’ departure and Collins was unable to fly for some reason.

That he was assigned the joint back-up position on Apollo 11 also meant Mattingly took over Anders’ spot as Command Module pilot for Apollo 13, continuing the loose partnership started with Jim Lovell (Apollo 13 commander) and Fred Haise (Lunar Module pilot). They formed a particularly good team together, but plans had to change three days ahead of the launch after Mattingly revealed he’s be exposed to someone with rubella. Standard policy called for his back-up for the mission (John “Jack” Swigert) to replace him to avoid any complications caused should he fall ill during the mission.

As a result of this, Mattingly was on the ground following the explosion which crippled Apollo 13’s Service Module. He immediately joined the teams ordered to recover the mission, using his knowledge of various simulations to suggest who could be called upon to provide specific expertise – such as cobbling together an air circulation system between command module and lunar lander.

After the command module had to be completely powered-down in the hope of conserving the battery power it would need in order to successfully re-enter the atmosphere and deploy its parachutes, Mattingly was assigned to the team charged with working out exactly how to re-start the command module’s electrical and guidance systems, given this was part of their design parameters – and to do so with a very limited power budget.

In the film Apollo 13 this saw Mattingly – as played by Gary Sinise largely leading the way in this work and bouncing in and out of the simulator. However, as the real Mattingly was quick to point out after seeing the film, reality was a lot less dramatic, comprising working through reams of documentation and data on the Command Module with a team led by Flight Controller John Aaron, and using the information to slowly and methodically write-up a clear set of procedures to bring the Command Module back to life. Only after this was all done was there any simulator hopping

We said, “Let’s get somebody cold to go run the procedures.” So I think it was [Thomas P.] Stafford, [Joe H.] Engle — I don’t know who was the third person, might have been [Stuart A.] Roosa. But anyhow, they went to the simulator there at JSC and we handed them these big written procedures and said, “Here. We’re going to call these out to you, and we want you to go through, just like Jack will. We’ll read it up to you. See if there are nomenclatures that we have made confusing or whatever. Just wring it out. See if there’s anything in the process that doesn’t work

– Ken Mattingly on developing the restart procedures for the Apollo 13 Command Module

That the vetting of the procedures went smoothly and afterwards, Fred Haise on Apollo 13 was able to receive them over the radio and follow them without major hiccup is testament to the speed and care with which Mattingly, Aaron and their team were able to work, bringing together the final vital part of the puzzle together in order to bring the crew home.Mattingly finally got to orbit the Moon in April 1972 as the Command Module pilot for Apollo 16. By another of the quirks of fate which seemed to mark his entire career, his commander for that mission was Jim Young and the Lunar module Pilot was fellow Aerospace Research Pilot School instructor Charles Duke. While the latter went down to the surface of the Moon, Mattingly remained in orbit, performing a battery of experiments – some of which required he complete a EVA during the return leg to Earth in order to collect film and data packages from equipment in the science bay of the Service Module.

Opting to remain with NASA as Apollo’s lunar missions were rapidly wound-down (causing a number of his colleagues to depart the agency to go back to their military careers or the private sector), Mattingly rotated through a number of key positions in managing the development of the space shuttle. This led to his first shuttle mission assignment as commander of STS-4 in 1982.

This was a week-long mission – the final in a series of four so-called “test flights” – timed to end on Independence Day 1982, with the landing at Edwards Air Force Base, California serving as the backdrop for then President Ronald Regan to announce the Space Transportation System was to henceforth be regarded as “operational”. In another twist of fate the man selected to fly with Mattingly as the vehicle’s pilot, was none other the Hank Hartsfield, Mattingly’s other instructor from the Aerospace Research Pilot School and who was now subservient to Mattingly’s overall command (confusingly, and in difference to aviation, the pilot on most NASA missions is not the commander for the mission but rather the “co-pilot”).

Mattingly’s last flight to orbit came in January 1985, when he commanded the shuttle Discovery on mission, STS-51-C. This flight is chiefly remembered for two reasons: it was the first shuttle flight to be classified by the US Department of Defense, and it is the shortest shuttle mission on record – just 3 days. However, it also has two haunting links with the loss of the shuttle Challenger on mission STS-51-L just a year later. The first being that 51-C was the first (and tragically last) on-orbit mission for Ellison S. Onizuka, one of those killed during 51-L.

The second was that 51-C revealed the dangers inherent in launching a shuttle during extremely cold weather – if people had been willing to see the signs for what they were. At the time of its launch, Discovery lifted-off in the coldest temperatures recorded for a shuttle flight up to that time: just 12 ºC. Following the recovery of the mission’s solid rocket boosters, it was found that all of the o-rings on both boosters showed signed of charring as a result of exposure to flame – with one of the primary rings entirely burnt through and its secondary badly burnt.

Tests subsequently showed that in low temperatures, this rings – designed to seal the joints between the major segments of the solid rocket boosters – both lose their ability to flex in response to dynamic pressures exerted both from within the boosters as they burn their propellants and from the surround air through which the shuttle system is trying to punch its way, and they become brittle and subject to burn-through. Despite these findings, Challenger was allowed to launch on mission 51-L after it had been exposed to temperatures fifteen degrees lower than those experienced at the launch of STS-51-C – and tragedy followed.

After completing his third space flight and at the age of 49, Mattingly opted to retire from NASA and return to the Navy, having been promoted to Captain whilst on secondment to the space agency. He then retired from the Navy just over a year later, having reached the rank of Rear admiral (upper half), and perused a career in the private sector, where his expertise in fight systems was much sought after by major NASA and defence contractors, allowing him to work for several – including Lockheed Martin

At Lockheed, he was charged with overseeing the attempted development of a technology demonstrator – the X-33 – intended to be the forerunner of a new single-stage to orbit vehicle called VentureStar. Unfortunately, the X-33 proved to be a little too ambitious in its use of advanced materials, with NASA cancelling the programme which supported it in 2001, with the VentureStar programme at Lockheed going the same way. Having reached the age of 65, Mattingly opted to retire from business.

Mattingly remained modest about his career as an astronaut, largely eschewing the limelight and avoiding memoirs – although he would attend events and give talks in order to inspire young people to entire the sciences. At the time of his death, he and his wife Elizabeth, whom he had married in 1970 and with whom he had a daughter, were residing in Arlington, Virginia. In officially announcing his passing, NASA released a statement from Administrator Bill Nelson, which in part paid this tribute:

NASA astronaut Thomas K (TK) Mattingly was key to the success of our Apollo Programme, and his shining personality will ensure he is remembered throughout history. TK’s contributions have allowed for advancements in our learning beyond that of space. As a leader in exploratory missions, TK will be remembered for braving the unknown.

– NASA Administrator Bill Nelson.

China Demonstrates Reusable Rocket Stage in Remarkable Test

On November 2nd, 2023, a Chinese commercial rocket system developer, Beijing Interstellar Glory Space Technology Ltd – more generally (and less pompously) referring to itself as i-Space† – demonstrated it is well on the way to developing a semi-reusable launch vehicle which is due to commence orbital flights in 2025.

The company – formed in 2016 – is aggressively perusing space flight on a number of fronts, from offering a smallsat launcher in the form of its Hyperbola 1 rocket (aka Shuang Quxian-1), capable of lifting up to 300 kg to low-Earth orbit (LEO), and which has seen admittedly mixed results – from the first Chinese privately-operated rocket to successfully place payloads in orbit to three back-to-back failures; to designs for a sub-orbital space plane with which it hopes to enter the space tourism sector.

However, it is in the field of reusable rocket systems that i-Space is particularly focused. They have already developed two liquid methane / liquid oxygen (“methlox”) rocket motors which are capable of variable thrust and of shutting down and restarting. The first of these motors was to have been used on their Hyperbola 2 rocket, but such have been the results gained from static fire tests of both that motor, the JD-1, and the larger Focus-1, i-Space announced in July 2023 that it was scrapping the Hyperbola 2 and pushing ahead with Hyperbola 3.

This is a medium-lift, semi-reusable rocket which might be thought of as the “little Chinese cousin” to SpaceX’s Falcon 9, being capable of placing payloads up to “at least” 8.5 tonnes to LEO with the first stage reused, and up to “at least” 13.4 to LEO if the first stage is expended. Also, and like Falcon 9, Hyperbola 3 will be capable of having three first stages strapped together to form a “heavy” variant akin to Falcon Heavy, with a payload-to-LEO capability of “at least” 15 tonnes. The company intends for the rocket to enter service in its expendable form in 2025, with the launches where the first stage is returned to Earth and re-used commencing in 2026.

The November 2nd flight test saw a 17-metre tall test article called Hyperbola 2Y and equipped with a Focus-1 engine undertake the latest in a series of iterative development tests. In it, the vehicle went from a standing start to full thrust, lifting itself to an altitude of 178 metres – marking the vehicle’s first free flight – hovering for a second or two, and then gently lowering itself back down over the pad at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre, where it again hovered just a metre or so off the ground before gently touching down. The entire flight lasted just 51 seconds, but was an impressive display of the engine’s capabilities, and those of the on-bord guidance system in manoeuvring the rocket and in countering wind forces to maintain its position over the test stand so it could land almost directly on the spot from which it took off.

It is not clear as yet as to if / when i-Space will carry out further flights of this nature, but given their approach of rinse, wash, repeat in order to gather a broad range of data from multiple engine static fire tests over the last couple of years, it would seem likely more flights like this, possibly to higher altitudes, might expected.

† Not to be confused with the Japanese company ispace Inc, which is primarily focused on the development of robotic craft for use on the Moon.