3D printing may be a relatively new technology, but it is one that is revolutionising may sectors of industry and commerce – and that includes space exploration. I’ve already covered the work of Relatively Space to manufacture and operate the world’s first 3D printed rocket systems in the form of the (now retired after it maiden launch failure) Terran 1, and the highly ambitious, semi-reusable Tarran R. However, NASA has actually been charting the potential for 3D printing in space and on Earth for almost a decade.

As an example of this; the first 3D printing system installed on the ISS arrived in 2014. It was a modest affair primarily designed to research whether or not practical, plastic-based 3D printing could be used in the microgravity of space. As the analysis of the printed parts demonstrated, there were no weaknesses or deficiencies in their construction when compared to identical items produced on Earth using the same process. Thus, the initial project was expanded to encompass the production of usable items – a wrench, plastic brackets, parts of an antenna system, for example – using a variety of industrial-grade plastic filaments.

The capability was then enhanced with the arrival of ReFabricator – a system which could take plastics used on the ISS and recycle them into plastic filament for use by the printer, with Recycler later adding the ability to do the same with other “waste” materials on the station.

In 2023, the European Space Agency and Airbus Industries went a stage further with Metal3D, a printer capable of producing metal and alloy parts for use on the ISS. It is part of a broader project to develop in-situ orbital and lunar 3D printing systems capable of manufacturing everything from replacement parts to entire assemblies such as radiation shields, vehicle trusses, etc. ESA plan to use an enhanced Metal3D system to use lunar regolith as its raw material in the production of equipment and components.

Meanwhile, NASA has also been busy on Earth with a range of 3D printing projects and studies, one of which – RAMFIRE – which earlier in the year had its (quite literal) baptism of fire.

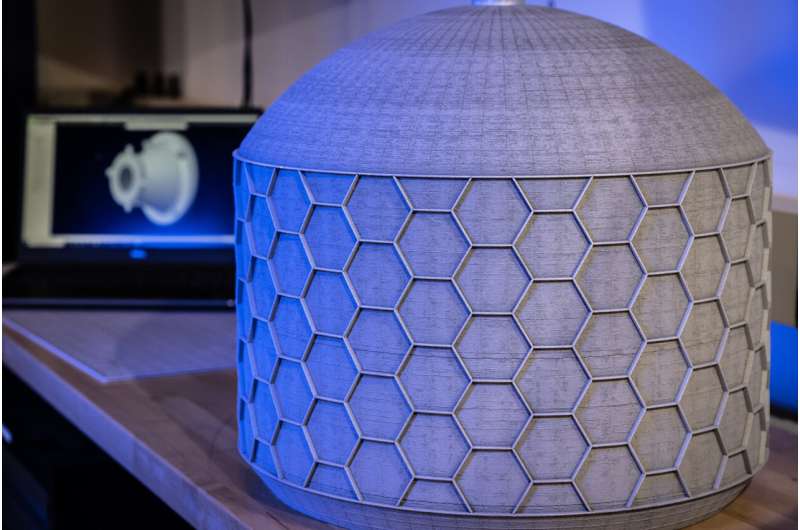

Standing for the Reactive Additive Manufacturing for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, RAMFIRE is a unique process which combines an entirely new aluminium alloy called 6061-RAM and 3D printing to create rocket nozzles for space vehicles. To understand why it is potentially so revolutionary, three points need to be understood:

- As a rule, aluminium is a poor choice for rocket engine (and particularly engine nozzle) construction as it has a rather nasty habit of melting when exposed to high temperatures – such as those generated by a rocket engine nozzle.

- While aluminium can be strengthened to withstand higher temperatures through the use of additives, the additives themselves can make it susceptible to cracking and microfractures if the aluminium has to be wield to itself or other items as is again required in the production of rocket nozzles.

- At the same time, being able to print an entire engine nozzle as a single unit and in aluminium, has the potential of both greatly simplifying the process of rocket engine production (as the nozzle now comprises a single part, rather than up to 1,000 individual parts as is currently the case, and for the engine to be significantly lighter without any reduction in thrust, allowing for a potentially large payload to be carried.

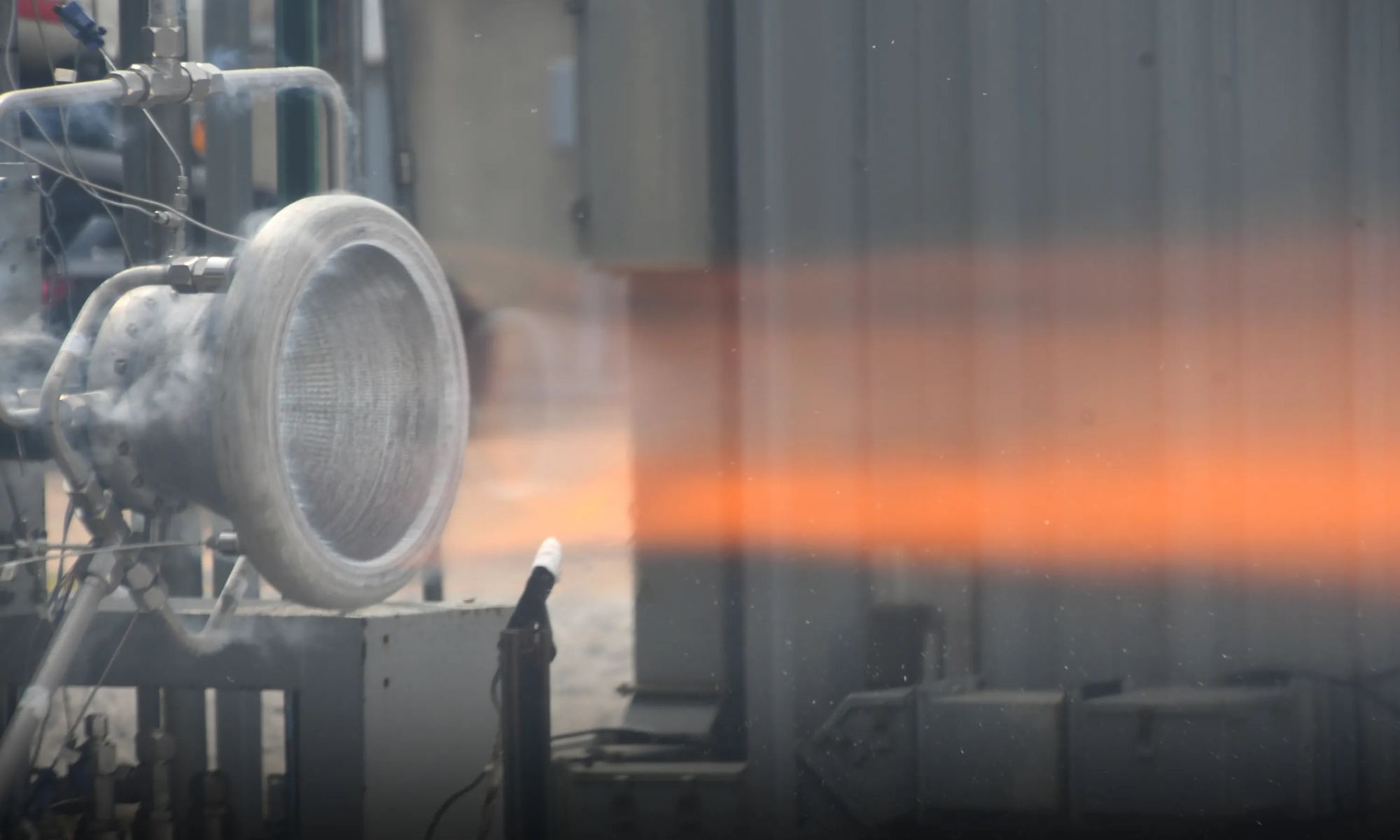

Using 6061-RAM with a 3D printing process developed in partnership with Colorado-based Elementum 3D, NASA has been able to produce single-piece aluminium rocket nozzles which, by a combination of the additives used in the alloy and a series of special cooling channels printed into the nozzles, both withstand the heat of combustion in their chambers and also passively cool themselves in the process.

Over the summer period, two small-scale RAMFIRE nozzles were put through their paces at NASA’s Marshall Space Centre in a series of hot fire tests, the results of which were published by NASA on October 16th. The nozzles were tested using two cryogenic propellant mixes – liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen in one batch of tests, and liquid oxygen and liquid methane in the other. It had been anticipated the nozzles would manage a pressure of up to 625 psi in their chambers, and run for a handful of minutes apiece. As it turned out, they functioned above the anticipated pressure without damage and racked up a cumulative burn time of almost 10 minutes.

This level of burn time and pressure is well in excess of the major requirement for such engine nozzles: within cargo transports carrying payloads to the surface of the Moon and landing them safely, bore lifting off again for the return trip to Earth to collect more cargo. However, the technology being developed by NASA and Elementum 3D has the potential to be used in a wide range of space vehicle applications, from propellant tank manufacture through to providing a means to provide very lightweight, thrust-efficient aerospike engines, one of the holy grails of space transportation systems.

There is still further R&D to go with RAMFIRE, but NASA and Elementum 3D are already looking at licensing 6061-RAM and the printing process to commercial organisations interested in adapting it for use in their space-based efforts – and possibly further afield in aerospace research sectors.

14,000 Ways to Smash a City (and 50 Ways To Do Far Worse)

The potential for an asteroid or other natural object orbiting the Sun to impact the Earth with devastating effect is a subject these pages have covered a number of times. Truth be told, our planet is constantly being bombard all manner of materials from space – but fortunately, the vast majority of it is far, far too small to do any damage whatsoever, burning up high up in the upper reached of the denser part of our atmosphere.

However, there are thousands of rocky chunks zipping around the Sun close enough to us such that were one of them to meet Earth head-on, the results could be catastrophic.

For example, in 1908 a fragment of rock roughly 50-60 metres across struck Earth’s atmosphere at a velocity of around 27 km/s. Enough of it survived to fall to an altitude of between 5 and 10 km before air pressure overcame it, and it explosively shattered with a 12 megaton force above the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in what is now known as Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. In doing so, it flattened an estimated 80 million trees covering an area of 2,150 sq km.

Now known as the Tunguska event, it generated a shockwave so powerful, it shattered windows hundreds of kilometres from the epicentre of the explosion, and left so much material in the atmosphere afterwards the skies from Europe to Asia were reported to glow at night due to the dust reflecting the Sun’s light long after it had set; so much so that in places like Scandinavia and Scotland, people were able to take outdoor photographs at night without needing flash systems for artificial illumination.

It must have been an awe-inspiring sight. But just think of what might have happened if that same fragment detonated 5-10 km above London or Paris or Moscow or Beijing or New York…

As a side note, the object responsible for that event came from a cloud of debris left after a comet believed to be around 40-km diameter was torn apart by the actions of solar and planetary gravity some 10,000 years ago. The Earth still passes through that cloud of debris as the paths of it and the debris cross one another annually as both circle the Sun, giving rising to the meteor showers we refer to as the Taurids.

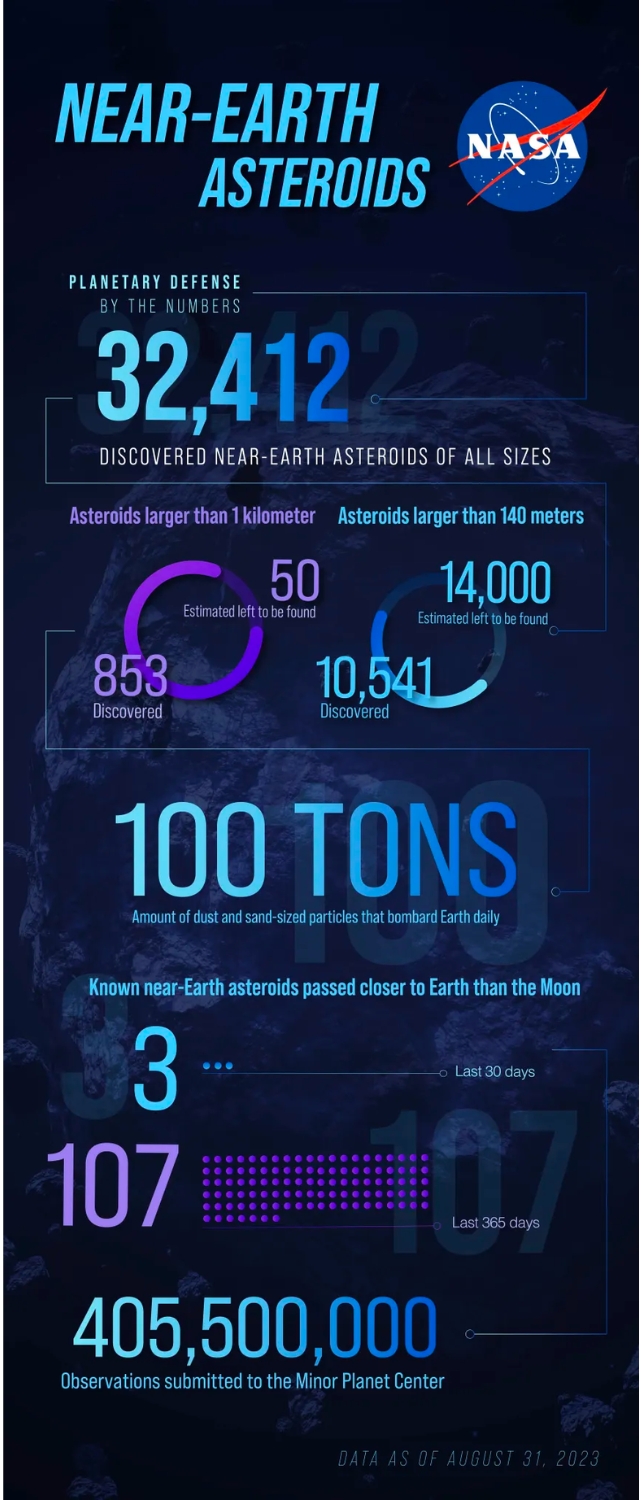

Over the last several decades, significant effort has been put into trying to locate asteroids and other rocky fragments with orbits around the Sun which bring them dangerously close to Earth and thus have the potential for a direct collision at some point in the future. NASA’s Minor Planet Centre is one of the major bodies tasked with cataloguing all of the observations and tracking of such objects, in on October 16th, they published an infographic intended to encourage more amateur and professional astronomers to join in with the work.

It reveals that to date, astronomers have been able to identify and track over 32,500 natural objects – which is an impressive figure. What’s more impressive is the fact it has taken over 405 million observations submitted to the Minor Planet Centre to enable these 32,500 objects to be positively identified and catalogued for routine observation, together with the fact that around 107 objects large enough to put a crimp in your day were one to strike near you, zip pass the Earth every year.

But what is possibly frightening in the infographic is that extrapolating the numbers, the Minor Planet Centre estimates there are some 24,500 such objects which 140 metres or larger in diameter – and we have thus far found less than half of them. So that’s 14,000 near-Earth objects (NEOs) at least two to three times the size of the Tunguska Event potential coming close enough to or actually crossing Earth’s orbit to offer the risk of a future collision. And that is a lot. Further, of those 14,000 an estimated 50-ish are believed to be a kilometre or more across; that’s large enough to wreak havoc on a global scale were one to strike us.

Of course, these figures are extrapolations – they could paint a picture than is bleaker than reality; but conversely, they could also be slightly over optimistic. Hence why NEO / asteroid hunting is such a global activity involving professionals and amateurs alike – and one where too many eyes making careful and precise observations night after night after night and reporting back to the Minor Planets Centre can never really be an issue.

Follow-Ups In Brief

India Aces Gaganyaan Crew Module Test

On October 21st, 2023, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) successfully completed a test of the crew escape system (CES) which will be used to pull crew-carrying versions of their new Gaganyaan space capsule system, as previewed in my last Space Sunday outing.

The rest saw a purpose-built rocket lift-off from Satish Dhawan Space Centre at 04:30 UTC, carrying an unpressurised test article of the Gaganyaan’s Earth return capsule. As it reached Mach 1.2 and at an altitude of 11.9 km, the rockets of the escape system fired, hauling the capsule away from the ascending rocket, some 61 seconds after launch.

Once the CES had powered the capsule clear of the rocket (as it would do in the event of a malfunction of a launch vehicle carrying a crew to orbit), it separated from the capsule, which continued on a ballistic arc, opening a drogue parachute to slow and stabilise its as it started on a descent back to Earth from a total altitude of over 17 km. At 2.5 km altitude, with the capsule suitably slowed enough, the main parachute deployed, allowing the capsule to make a successful splashdown some 10 km off the island of Sriharikota in the Bay of Bengal, where units from the Indian navy recovered it.

The test is one of two which will take place this year. They will pave the way for two uncrewed orbital tests of the entire Gaganyaan vehicle in 2024, which if successful will clear the way to the first crewed launch in 2025 which will mark India as the 4th nation to independently fly humans in orbit after Russia, America and China.

The test came in the wake of the Indian government announcing an aggressive crewed space programme over the next two decades. This will include flying the Bharatiya Antariksha Station, a modest (by ISS / Chinese standards) orbital facility massing around 20 tonnes and capable of supporting crews of 3 for up to 20 days at a time, plus an even more ambitious goal of independently landing a crew in the Moon “by 2040”.

Satellite Images “Gravy Stain” of Annular Eclipse

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite is an NNOAA / NASA mission to observe space weather and also the Earth’s climate. It sits within a halo orbit at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, 1.5 million km from Earth, and between the two. This offered it a grandstand seat to view the recent annular eclipse of the Sun – but in a rather unusual manner.

Looking back at Earth, the satellite was able to track the Moon’s shadow as the Moon slid between the Sun and Earth, allowing that shadow to slide across north and central America like a “gravy stain” oozing its way over an impermeable surface.

The satellite was one of several looking at Earth during the eclipse, but its position meant that it had perhaps the most unique and complete view as the event took place under its EPIC (Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera) eye.