3D printing may be a relatively new technology, but it is one that is revolutionising may sectors of industry and commerce – and that includes space exploration. I’ve already covered the work of Relatively Space to manufacture and operate the world’s first 3D printed rocket systems in the form of the (now retired after it maiden launch failure) Terran 1, and the highly ambitious, semi-reusable Tarran R. However, NASA has actually been charting the potential for 3D printing in space and on Earth for almost a decade.

As an example of this; the first 3D printing system installed on the ISS arrived in 2014. It was a modest affair primarily designed to research whether or not practical, plastic-based 3D printing could be used in the microgravity of space. As the analysis of the printed parts demonstrated, there were no weaknesses or deficiencies in their construction when compared to identical items produced on Earth using the same process. Thus, the initial project was expanded to encompass the production of usable items – a wrench, plastic brackets, parts of an antenna system, for example – using a variety of industrial-grade plastic filaments.

The capability was then enhanced with the arrival of ReFabricator – a system which could take plastics used on the ISS and recycle them into plastic filament for use by the printer, with Recycler later adding the ability to do the same with other “waste” materials on the station.

In 2023, the European Space Agency and Airbus Industries went a stage further with Metal3D, a printer capable of producing metal and alloy parts for use on the ISS. It is part of a broader project to develop in-situ orbital and lunar 3D printing systems capable of manufacturing everything from replacement parts to entire assemblies such as radiation shields, vehicle trusses, etc. ESA plan to use an enhanced Metal3D system to use lunar regolith as its raw material in the production of equipment and components.

Meanwhile, NASA has also been busy on Earth with a range of 3D printing projects and studies, one of which – RAMFIRE – which earlier in the year had its (quite literal) baptism of fire.

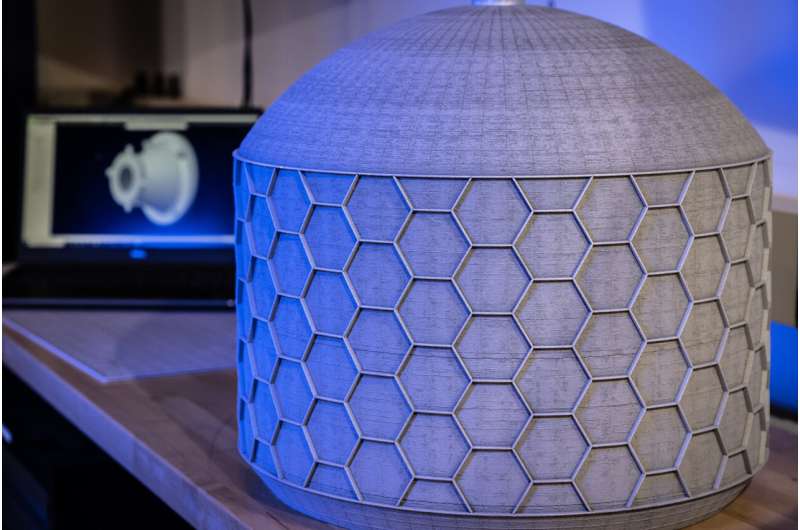

Standing for the Reactive Additive Manufacturing for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, RAMFIRE is a unique process which combines an entirely new aluminium alloy called 6061-RAM and 3D printing to create rocket nozzles for space vehicles. To understand why it is potentially so revolutionary, three points need to be understood:

- As a rule, aluminium is a poor choice for rocket engine (and particularly engine nozzle) construction as it has a rather nasty habit of melting when exposed to high temperatures – such as those generated by a rocket engine nozzle.

- While aluminium can be strengthened to withstand higher temperatures through the use of additives, the additives themselves can make it susceptible to cracking and microfractures if the aluminium has to be wield to itself or other items as is again required in the production of rocket nozzles.

- At the same time, being able to print an entire engine nozzle as a single unit and in aluminium, has the potential of both greatly simplifying the process of rocket engine production (as the nozzle now comprises a single part, rather than up to 1,000 individual parts as is currently the case, and for the engine to be significantly lighter without any reduction in thrust, allowing for a potentially large payload to be carried.

Using 6061-RAM with a 3D printing process developed in partnership with Colorado-based Elementum 3D, NASA has been able to produce single-piece aluminium rocket nozzles which, by a combination of the additives used in the alloy and a series of special cooling channels printed into the nozzles, both withstand the heat of combustion in their chambers and also passively cool themselves in the process.

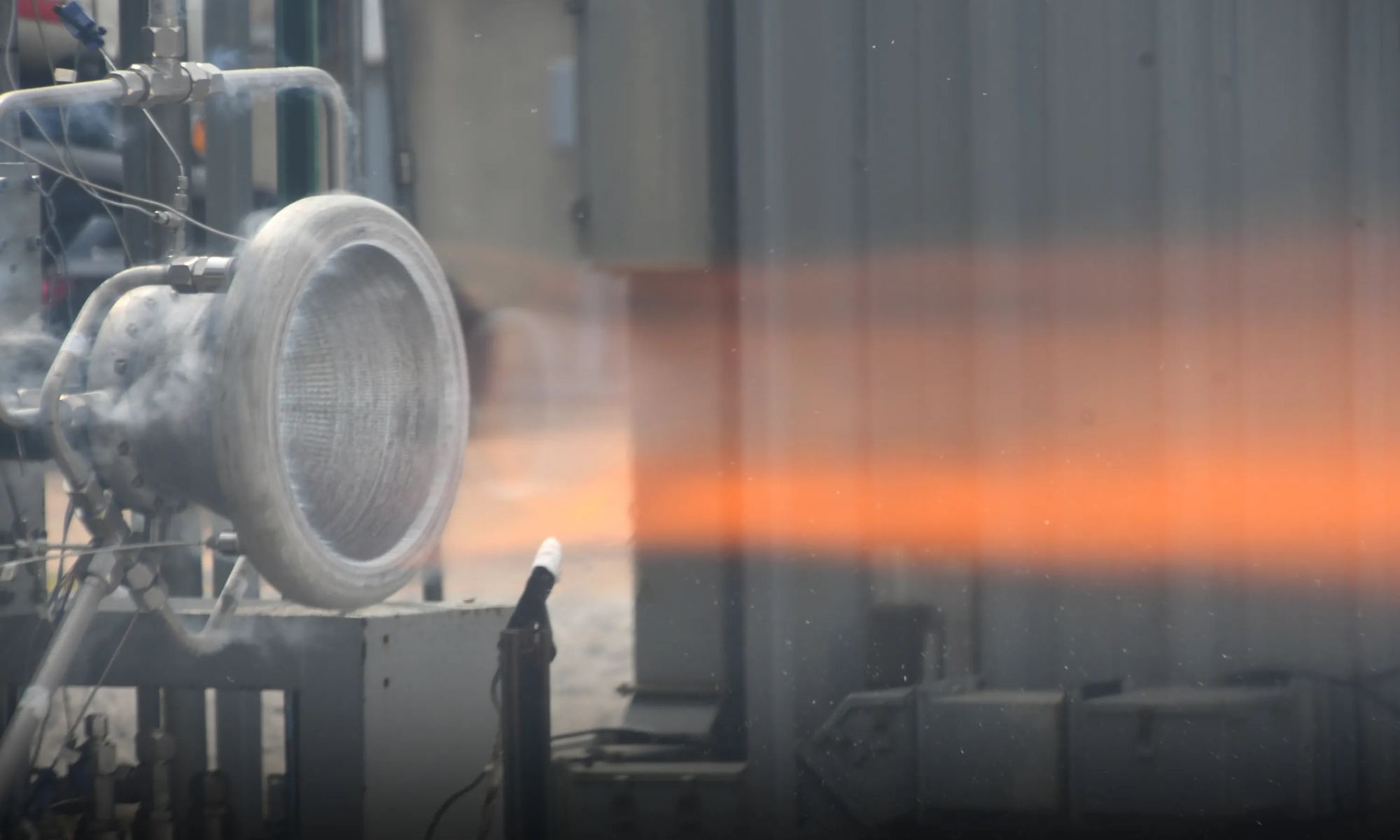

Over the summer period, two small-scale RAMFIRE nozzles were put through their paces at NASA’s Marshall Space Centre in a series of hot fire tests, the results of which were published by NASA on October 16th. The nozzles were tested using two cryogenic propellant mixes – liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen in one batch of tests, and liquid oxygen and liquid methane in the other. It had been anticipated the nozzles would manage a pressure of up to 625 psi in their chambers, and run for a handful of minutes apiece. As it turned out, they functioned above the anticipated pressure without damage and racked up a cumulative burn time of almost 10 minutes.

This level of burn time and pressure is well in excess of the major requirement for such engine nozzles: within cargo transports carrying payloads to the surface of the Moon and landing them safely, bore lifting off again for the return trip to Earth to collect more cargo. However, the technology being developed by NASA and Elementum 3D has the potential to be used in a wide range of space vehicle applications, from propellant tank manufacture through to providing a means to provide very lightweight, thrust-efficient aerospike engines, one of the holy grails of space transportation systems.

There is still further R&D to go with RAMFIRE, but NASA and Elementum 3D are already looking at licensing 6061-RAM and the printing process to commercial organisations interested in adapting it for use in their space-based efforts – and possibly further afield in aerospace research sectors.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: 3D printing for space, and asteroids”