On October 1st, 1958 the National Aeronautics and Space Administration officially commenced operations, just two months after then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the US National Aeronautics and Space Act into law.

NASA’s birth essentially arose out of what would become known as the “Sputnik crisis”. In October 1957 Russia launched Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite. Worse, just a month later, they launched Sputnik 2, which not only carried a living animal into orbit (the dog Laika, doomed to expire in orbit as the technology did not exist for the craft to re-enter the atmosphere and land safely), it demonstrated Russia had a launch system vehicle could be used relatively rapidly. This put US space launch efforts – activities largely split between the three branches of the military – into something of a tailspin, with the realisation that any civilian / science space programme could not be reliant on competing military programmes.

To this end, it was decided to place military space development under the auspices of a new agency within the US Department of Defense: the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA – now the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA), which was also charged with managing all aspects of emerging technologies research as they related to military use. Meanwhile, civilian space research would be placed in the hands of a new agency, with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) charged with coming up with a structure for that organisation.

Further haste was given to the need to determine the best direction of the US civilian space programme in May 1958, when Russia launched Sputnik-3 to mark the International Geophysical Year. Massing 1.3 tonnes, or 100 times that of the US satellite launched 3 months earlier with the same goal, Sputnik-3 demonstrated Russia had a payload to orbit capability well beyond anything within the United States, and a technical capability to fly large suites of science instruments on a single vehicle (12 instruments in the case of Sptnik-3).

In being instructed to study options for a new civilian space agency, the NACA was uniquely placed. Founded in 1915, it had (at that time) been at the forefront of aviation development in the United States for more than forty years, and following the end of the Second World War, it had become increasingly involved in aerospace research. For example, NACA was responsible for the initial design concept of what would become the X-15 hypersonic aircraft after developing and flying a number of supersonic craft during the early 1950s, and worked with the US Air Force to develop the vehicle from 1954 through until the establishment of NASA in October 1958.

After due consideration, NACA submitted a report and after reading it, James Killian, the then-chair of the Science Advisory Committee realised that NACA was not only well-placed to recommend what form the new space agency should take, it was ideally placed to become the foundation of the new organisation, informing Eisenhower via a memorandum the to Eisenhower stating the new agency should be formed out of a “strengthened and re-designated NACA, a going Federal research agency with 7,500 employees and $300 million worth of facilities” and which could expand its role “with a minimum of delay”. His suggestion was accepted and incorporated into the National Aeronautics and Space Act.

As a result of the decision to transition NACA into NASA, the new agency was able to hit the ground running, gaining three major research centres – Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, and Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, and the NACA budget and staff. In the months immediately following NASA’s establishment, those elements of the US Army and US Navy trying to build and operate orbital rocket systems were transitioned over to the new agency (including the US Army team utilising Wernher von Braun and other former German rocket engineers), together with the California Institute of Technology’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which has become world-famous as the developmental and mission operations centre for the majority of NASA’s robotic deep space missions.

As a part of its very first research activities, NASA took over the hypersonic X-15 programme mentioned above, overseeing all 199 flights of that craft along with the US Air Force. At that time NASA came into existence, the NACA and the USAF had been collaborating on the idea of extending the X-15 into an orbit-capable vehicle to be launched vehicle a family of modified missiles, thus allowing the US to gain valuable insight into the design requirements and operating nature of space-capable aircraft, which were even at that time being seen as the future of manned spaceflight.

In particular, the USAF was keen to gather data to help with a concept for a multi-role “space glider” which would evolved into the X-20 Dyna-Soar project of the early 1960s (although this was ultimately cancelled in 1963). However, NASA’s new leadership preferred a more cautious approach to putting men in space, determining primates should be flown first and recovered for post-flight study. Therefore, the X-15B concept, with its need for a skilled pilot at the controls, was rules out in favour of the less capable but easier to fly Mercury capsule. Thus was NASA’s manned spaceflight programme born.

Today, whilst still a relatively small organisation in terms of manpower when it comes of federal agencies (the Federal Aviation Administration, for example, numbers 48,000 employees to NASA’s 18,000), and with a modest budget (less than US $26 billion from the US mandatory federal budget of US $4.1 trillion – which admittedly and conversely is still around 4.5 times more than the FAA’s), NASA is an incredibly diverse and far-reaching organisation.

Not only does it manage all of America’s civilian space activities through ten major research and operations centres across the United States (as well as numerous smaller facilities and centres), it continues to carry out wide-ranging aeronautical research and development in what is a continuance of the cutting-edge work started by the NACA more than 100 years ago.

In addition, NASA is involved in R&D and operations across many disciplines and areas of research, including communications; vehicle and transportation safety; environmental monitoring (climate and weather in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); pollution control, environmental management, global land use, deforestation monitoring, agricultural monitoring, etc (much in partnership with the US Geological Survey, or USGS); research into alterative and sustainable energy systems; nuclear research; multiple avenues of general science research as they pertain to the planet and to healthcare; and in promoting education, science, mathematics and the harnessing of technology through a range of STEM initiatives in the US and around the world.

So, happy anniversary NASA. You may be at retirement age in human terms – but here’s to many more!

Updates

OSIRIS-REx Samples

Previously on Space Sunday (as they say on TV shows) NASA’s ORISIS-REx mission returned to Earth samples captured from 101955 Bennu, a carbonaceous near-Earth asteroid. As we left that story, the sealed capsule containing the estimated 250 grams of material was pending a transfer to NASA’s Johnson Space Centre (JSC), Texas.

That transfer occurred on Tuesday, September 26th, 2023, with the sample capsule being airlifted from the US Army’s Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, some 31 kilometres from where it landed, to Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base near Houston, Texas. From here the special transpiration container with the capsule inside was move by road to the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science (ARES) centre at JSC.

ARES is home to the world’s largest collection of “astromaterials” (samples returned from space), and is usually the first US centre to examine such samples brought to Earth by US space missions. As such, it is the ideal permanent home for the OSIRIS-REx samples, and will be the centre that carries out an initial sample analysis and then divvy it up for distribution to research centres around the world and to museums.

How it should have gone – the OSIRIS-REx TAGSAM “touch-and-go” mechanism recovering samples from the surface of asteroid 101955 Bennu in 2020. As it turned out, the asteroid’s surface was so brittle, the sample head and arm smashed through it to a depth of around 50cm.

In preparation for this, ARES established a dedicated clean room for the mission, and the sample capsule was delivered directly to that facility following its arrival in Texas. Once inside, the capsule was moved to a custom-built glove box for unsealing and recovery of the samples.

This recovery comprised a multi-step process, commencing on September 27th with a partial disassembly of the sample return capsule to expose the mechanism in which the TAGSAM head and samples are sealed. Following this, the lid of the this mechanism was carefully unbolted from the capsule and lifted clear to expose the TAGSAM head itself, thus allowing it to be disassembled and the sample canisters reached. These steps were conducted methodically and cautiously, with each piece of hardware being checked for material from the asteroid, prior to being catalogued and stored for its own examination and analysis following their 7-year round-trip through space and searing entry back into the Earth’s atmosphere.

Once accessed, the sample containers were to be checked to ensure they were properly sealed, prior to prepped for opening and having their contents removed for initial examination, cataloguing and characterisation. If all goes to plan, NASA will announce the results of this initial review together with images and video of the sample unpacking at 15:00 UTC on October 11th.

The End of an Unexpected Stay

At: 11:17 UTC on Wednesday, September 27th, 2023, Soyuz capsule MS-23, fired its braking rockets to help cushion its return to Earth within its designated landing zone in Kazakhstan. Thumping down, the landing brought to an end to the unexpectedly long visit the three men on board had made to the International Space Station (ISS).

Roscosmos cosmonauts Sergey Prokopyev and Dmitri Petelin and NASA astronaut Frank Rubio had departed Earth for the ISS on September 21st, 2022 for a planned 6-month stay on the ISS. However, a major hole was – literally – punched through their mission schedule when on Thursday, December 24th, 2022, their Soyuz MS-22 vehicle, due to return them to Earth in March 2023, suffered a crippling coolant leak, rendering it unsafe for any crewed return flight other than in an emergency.

Shortly after the accident and confirmation the capsule could not support a crew of three through entry into Earth’s atmosphere, it was decided to bring forward the launch of the Soyuz M-23 mission, and send that vehicle to the ISS without a crew so that Rubio and his colleagues to use it to come home. However, the wrinkle in the plan was that all three men would have to remain on the station for an additional 6 months and perform the work planned for the crew would have otherwise flown to the station in March 2023 to replace them (that crew – redesignated the crew of MS-24 – arrived at the ISS on September 15th), paving the way for Rubio, Petelin and Prokopyev to finally depart the ISS and come home.

As a result, the three MS-22/23 crew spent a total 371 days in space, the third-longest spaceflight after the 438 days spent by Valeri Polyakov in 1994 and 1995 and 380 days spent by Sergei Avdeyev in 1998 and 1999, both aboard the Mir space station. However, Rubio, Petelin and Prokopyev now hold the joint record for the longest stay on the ISS, whilst Rubio taken the record for the American with the longest time space in space during a single mission, surpassing the 355 days set by Mark Vande Hei in 2021 and 2022.

Besides allowing the three to complete the mission earmarked for the original crew of MS-23, the extended stay on the station by Rubio and his colleagues helped gather further information, notably that of the psychological impact – given doubling their stay on the ISS away from family and loved was not something the three men nor their families has either trained for or expected -, of a long duration space mission can have on a single crew working together for an extended period.

Chandrayaan 3 Remains Silent as the Lunar Day Rapidly Passes

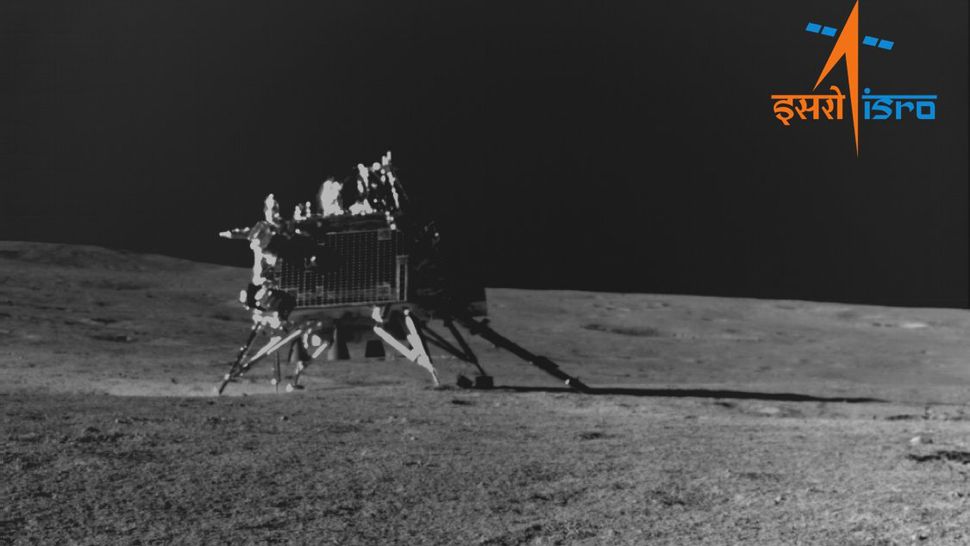

India’s Vikram lunar lander and its attendant Pragyaan rover – together forming the Chandrayaan-3 mission – remain dormant, despite the return of sunlight to their landing site within the Lunar South Polar Region.

Following a 14 terrestrial day period without sunlight in which it had been hoped the two craft would be able to withstand very low temperatures by relying on the heat generated by their batteries to keep their electronics warm (neither having any dedicated heating systems for this due to size / mass constraints), attempts were initially made to contact the lander and the rover after the Sun has again risen over their landing site on September 22nd. However, by September 28th – effectively noon at the landing site – no response had been received, and while the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is not quite ready to state the mission is ended, the likelihood of receiving any response is rapidly diminishing.

Which is not to say the mission is a failure – as I previously noted, both Vikram and Pragyaan completed all their primary mission objective ahead of schedule, allow both to enjoy a period where they could use the last of the sunlight before the long lunar night set in to recharge their batteries to full capacity in the hopes of riding out the night and remaining operational through at least another lunar day.