Due to launch in just under 2 months, on or shortly after October 5th, 2023, NASA’s Pysche mission is intended to explore the origin of planetary cores by studying the metallic asteroid of the same name.

The 14th mission in NASA’s Discovery programme, the spacecraft is currently going through the last of its pre-launch preparations, the latest being the installation and folding of its massive solar arrays.

With a total span of almost 25 metres and covering a total area of 75 square metres, these are among the largest arrays used on a NASA deep-space mission. They will be capable of generating 20 kilowatts of power during the early phases of the mission as the spacecraft departs Earth, where they will be primarily used for the purposes of vehicle thrust. However, Psyche is so far from the Sun that by the time the craft arrives, they will only be able to generate around 2 kilowatts – enough to boil two kettles side-by-side.

For propulsion, the spacecraft will use four Hall-effect thrusters (HETs). Based on the discovery by Edwin Hall after whom they are named, these are a form of ion propulsion in which the propellant – most often xenon or krypton gas – is accelerated by an electric field. They provide an efficient thrust-to-propellant load ratio, allowing the spacecraft utilise a minimum propellant load – around a tonne – for the 5 year 10 months transit to asteroid 16 Psyche and the 21-month primary science mission.

The overall thrust produced by the HETs is equivalent to holding a single AA battery in the hand. However, as they can run for extended periods, they will be able to gently accelerate the spacecraft to 200,000 km/h during the 4 billion kilometre cruise out to the asteroid belt. They will also provide sufficient thrust to allow the spacecraft to slow itself and enter orbit around the asteroid in readiness to start its science mission.

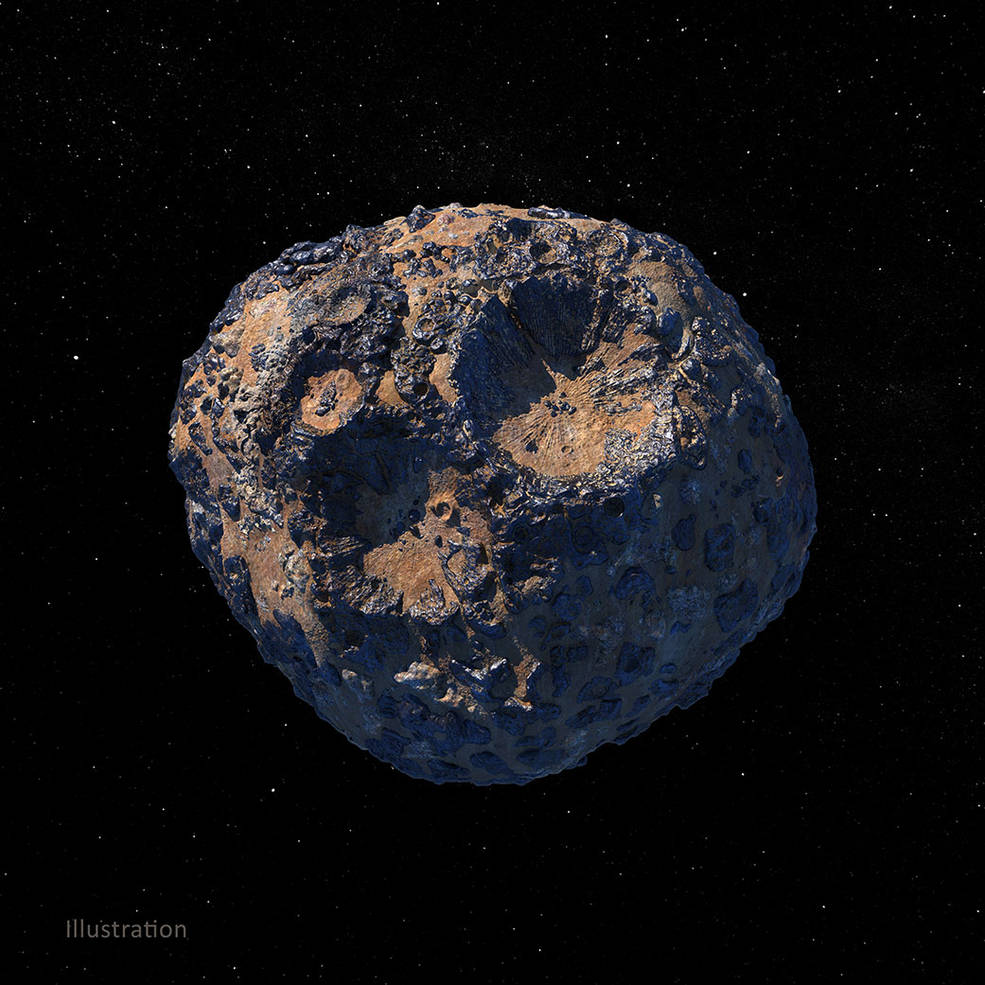

16 Psyche is the heaviest known M-type asteroid – those with higher concentrations of metal phases (e.g. iron-nickel) than other asteroids – in the solar system. It was in 1852 by Italian astronomer Annibale de Gasparis, who named it for the Greek goddess Psyche, with the “16” prefix indicating it was the sixteenth minor planet to be discovered.

Initially, it was thought that asteroid was the exposed iron core of a protoplanet, exposed after a violent collision with another object that stripped off its mantle and crust. However, more recent studies lean heavily towards ruling this out – but it still might be a fragment of a planetesimal smashed part in the very earliest days of the solar system’s creation. As such, studying the asteroid might answer questions about planetary cores and the formation of our own planet.With the solar arrays installed and stowed, the next significant milestone for the mission will be the loading of the xenon propellant, which will occur over a two-week period starting in mid-August. This will be followed by the spacecraft being mated with its payload mount and then integrated into the upper stage of the SpaceX Falcon Heavy which will launch the mission from Kennedy Space Centre’s Pad 39B.

Euclid Arrives at L2 and Starts Commissioning Tests

The European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Euclid space telescope has arrived in orbit around the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, and commissioning of its science instruments has commenced.

As I noted in Space Sunday: a “dark” mission, recycling water and a round-up, Euclid is a mission intended to aid understanding of both dark matter and dark energy – neither of which should be confused with the other. Euclid will do this by creating a “3D” map of the cosmos around us, plotting the position of some two billion galaxies in terms of their position relative to the telescope and the redshift evident in their motion.

From this, astronomers will be able to study the clustering effects of dark matter, the cosmic expansion of dark energy, and how cosmic structure has changed over time. It will be the largest and most detailed survey of the deep and dark cosmos ever done.

Following a 30-day transit from Earth, Euclid entered into orbit around the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, 1.5 million km from Earth, at the end of July, and commissioning of its instruments – which had undergone power tests whilst en-route – commenced almost at once, with early result being released.

Over the next 6 years, Euclid will observe the extragalactic sky (the sky facing away from the bulk of our own galaxy) in what is called a “step and stare” method: identifying a section of sky and training both of its camera systems, one of which images in visible wavelengths and the other in infrared, before moving on to the next, generating “strips” on imaged squares.

In doing so, Euclid will capture light from galaxies that has taken up to 10 billion of the universe’s estimated 13.8 billion-year lifespan to reach us. In doing so, it will measure their shape and the degree of red shift evident, whilst also using the effects of gravitational lensing on some to reveal more data about them.

The data gathered is intended to help astrophysicists construct a model to explain how the universe is expanding which might both explain the nature and force of dark energy and potentially offer clues as to the actual nature of dark matter – the mass of which must be having some impact on dark energy as it pushes a the galaxies.

In all, it is anticipated that Euclid will produce more than 170 petabytes of raw images and data during its primary 6-year mission, representing billions of stars within the galaxies observed. This data will form a huge database that will be made available globally to astronomers and researchers to help increase our understanding of the cosmos and in support for current and future missions studying the universe.

Curiosity Celebrates 11 Years on Mars by Completing Tough Challenge

Since arriving on Mars in February 2021, the Mars 2020 mission with Perseverance and Ingenuity has tended to overshadow NASA’s other operational rover mission on Mars, that of the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity, which arrived within Gale Crater on August 6th, 2011.

In that time, the mission has scored success after success, doing much to reveal the water-rich history of the crafter – and the history of Mars as a whole. For the last several years the rover has been slowly climbing “Mount Sharp” – the 5 km tall mound at the centre of the crater – and officially called Aeolis Mons – revealing how it is the result of the crater being the home of several lakes during Mars’ ancient history.

Most recently, the rover has faced its toughest challenge yet: attempting to ascend a ridgeline setting between it and an area of geological interest dubbed “Jau”. From orbit, the ridge appeared to be difficult, but not impossible for the rover. However, it combined three obstacles which proved troublesome: a steep slope averaging 23o and which comprises a mix of sand dunes and boulders large enough to pose a threat to the rover’s already battered wheels.

Initial attempts to get over this ridge in April and June resulted in the rover hitting “faults”: stoppages triggered automatically as the wheels start slipping, either as a result of the ground beneath them being too soft to offer traction meeting a resistance such as a too-large boulder they could not overcome. These forced the mission team to take a chance on a 300 metre diversion to try a point on the ridge which appeared to be less challenging.

The diversion proved worthwhile; despite taking several weeks to plan and execute, Curiosity managed to reach “Jau” – an area of multiple impact craters in close proximity to one another – in early July, and has been studying it at length.

Overcoming the ridge is a significant achievement for the rover, and clearly it means Curiosity should have something of a smoother passage to its next destination.