This article is designed to be the second part of a short series offering personal thoughts on the broad state of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR, together with mixed reality, or MR) as they appear to stand at the end of 2018, and where they might be going over the course of the next few years.

In doing so, I’m not attempting to set myself up as any kind of “expert” or offer predictions per se; I’ve simply been gorging myself on a wide range of articles and reports on VR and AR/MR over the last few weeks to make sure I’m caught up on things. In part one, I covered VR; This part therefore examines AR/MR, with an emphasis on headset / eye wear, as it is these tools that particularly interest me.

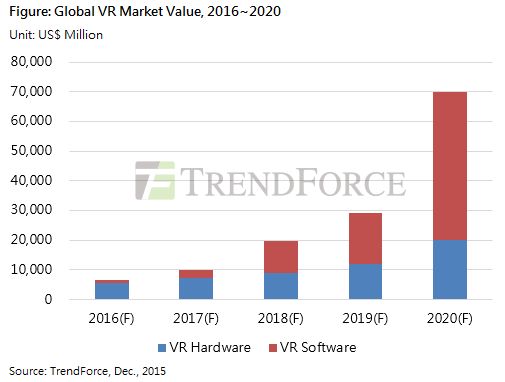

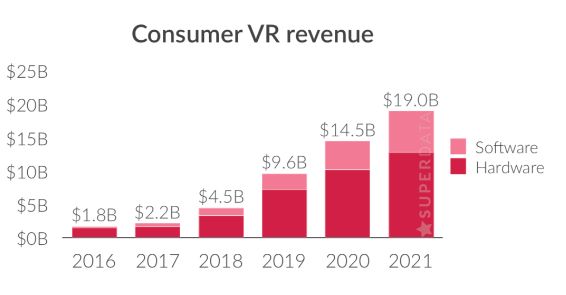

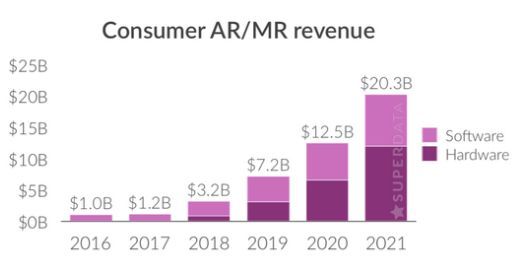

Compared to VR, AR/MR has been much more a slow burner in terms of press interest. The reason for this is simple: outside of a few headliners like the original Google Glass, Microsoft’s HoloLens and, most recently, Magic Leap One, AR/MR eye wear hasn’t really caught the media’s attention. However, in assessing the state of the VR and AR/MR markets over the next 3 years, SuperData predicts something of a rapid rise in AR/MR adoption, which could see the technology generate revenues very slightly in excess of those predicated by SuperData for VR by the start of 2022.

Even allowing for these figures including smartphone AR applications, this forecast might seem optimistic, but there are reasonable grounds to suggest they are not beyond the realm of possibility – if, perhaps a slightly holistic view is taken. I say this for a number of reasons: the increasing use of AR/MR in a range of workplace / service environments; the release of development platforms for AR on smartphones and mobile devices; and availability / development of new headsets; although there are some caveats.

I’d like to examine these ideas in turn, starting with adaptation of AR/MR in enterprise-type environments. In doing so, I’m limiting myself to briefly covering just three examples: Google’s Glass Enterprise Edition, Microsoft’s HoloLens and a company called Osterhout Design Group (ODG).

- Using the basic Google Glass concept (2013-2015) Glass Enterprise Edition re-lunched in mid-2017 with 50 US companies using it in engineering, training and services including GE Aviation, Boeing, Volkswagen, AECO, and DHL, and with a range of healthcare uses, including Augmedix and Brain Power (see Google Glass: The Comeback?, July 2017 for more).

- Microsoft’s HoloLens has been similar adopted by a range of companies including Volvo Cars, Japan Airlines, BlueScope Buildings and Trimble (architecture and building design), Autodesk, together with widespread adoption in healthcare from training through to major aspects of surgery in hospitals around the world. Most recently, the US Army has given Microsoft US $480 million to develop the HoloLens for troop training and combat missions, while NASA utilises it both on the International Space Station (Project Sidekick) and as a mission / prototyping visualisation tool (projects OnSight and ProtoSpace).

- Osterhout Design Group (ODG) – a company that potentially help Microsoft develop the HoloLens when they sold 81 patents related to AR and head-worn computers to the software giant for US $150 million in 2014. Have released a family of AR glasses, the R-7 and R-7HL (“hazardous locations”) specifically designed for use across business and industrial applications, providing heads-up information displays and overlays. In 2017, ODG launched the R-8 and R-9 glasses, utilising Qualcomm’s more powerful Snapdragon 835, with R-8 intended to start bridging the gap between “enterprise” and consumer use.

There are other examples of AR headset use in business (and entertainment) to be sure, but I hope the above are enough to make the point. Highlighting the use of AR systems in the workplace is important (as it is with VR – see part 1 of this series) because familiarity with them in the workplace could help spur people’s willingness to bring it into the home as affordable consumer systems start to appear, because: because a) they have experienced it within their workplace and have seen it benefit them; b) the hardware involved is (more-or-less) the “same” as the hardware they are buying (familiarly encourages both trust and experimentation).

Continue reading “Thoughts on VR and AR, part 2: AR, MR and beyond”