Japan’s ispace Inc., made its second attempt to place an automated lander on the surface of the Moon in the early hours (UTC) of June 6th, but unfortunately, things did not go well.

The Hakuto-R Mission 2, for which the lander was given the name Resilience, was a follow-up to the company’s first attempt to become the first Japanese private company to place a lander on the Moon in April 2023. That mission came to an abrupt end when the on-board flight computer disagreed with the vehicle’s radar altimeter and kept the vehicle in a hover some 5 km above the lunar surface until propellants were exhausted, and the vehicle made a final uncontrolled descent and impact.

Working with US partners, ipsace has been developing the Hakuto-R programme as a payload delivery service for customers involved in the lunar exploration industry, and also NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) designed to allow commercial organisations engage with the US space agency primarily in support of Project Artemis. In this respect, both the Mission-1 vehicle lost in 2023 together with this latest lander, were regarded as technology demonstrators, although both carried meaningful payloads.

Resilience was launched atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on January 15th, 2025, and followed a similar low-energy 5-month passage to the Moon as it forbear, gradually increasing its orbit around Earth before translating over to a lunar trajectory and entering orbit around the Moon on May 6th. On May 28th, the lander performed a final orbital control manoeuvre to enter a 100 km circular orbit above the Moon, targeting its intended landing site in the middle of Mare Frigoris (Sea of Cold), in the far north of the Moon, selected as it provides direct line-of-sight communications with Earth.

The aim of the mission was to successfully land and carry out several studies, including an in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) demonstration. It was also hoped the lander would deploy TENACIOUS, a European-built, small-scale rover weighing just 5 kg onto the surface of the Moon, which in turn carried a tiny model of a “Moonhouse”, a piece of art by Swedish artist Mikeal Genberg, as the culmination of a 25-year inspirational art project.

The initial descent of the 2.3m by 2.3m lander from lunar orbit appeared to go well. However, telemetry from the lander stopped one minute and 45 seconds before the scheduled touchdown, apparently due to an equipment malfunction.

A preliminary review of the flight data received on Earth suggests that the lander’s laser rangefinder experienced delays IN measuring the probe’s distance to the lunar surface. As a result, the lander’s descent motor failed to operate in sufficient time to decelerate to the required velocity for a safe landing, and the craft impacted the lunar surface in what ipsace refers to as a “hard landing”, meaning it is unlikely to have survived the event in any condition to proceed with its planned mission.

The loss of the vehicle is a double disappointment for ispace. Not only is it their second failure to land on the Moon, Resilience shared its launch ride with US-based Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost Mission 1. That craft took a similar but faster route to the Moon, allowing it to make a successful landing on March 2nd, 2025, becoming the first commercial lunar lander to do so and commence operations (see: Space Sunday: A landing, a topple, a return and another failure).

ispace are scheduled to deliver a much larger lander vehicle to the Moon in 2027, the APEX 1.0 lander, massing some 2 tonnes. This, with a follow-on mission the same year, is intended to establish ispace’s ability lander as a cost-effective, high lunch frequency craft capable of delivering multiple payloads to the Moon.

Blue Origin Reveals More on Lunar Landers and Transporter

In late May, Blue Origin provided an update on its hardware plans for supporting a human presence on the Moon, going into more detail about its Mark 1 and Mark 2 landers, and its all-important Transporter.

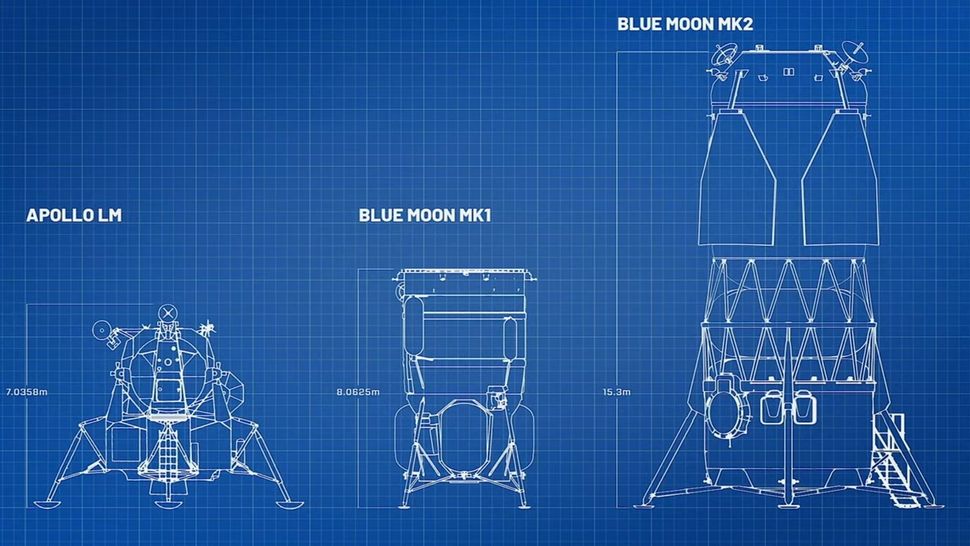

Contracted to develop and supply a crew-capable lunar lander as a part of NASA’s Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) contract within Project Artemis, Blue Origin is already well advanced with that vehicle (when compare to that of the SpaceX Starship-derived lander vehicle, which is supposed to be ready to fly next year), which is due to be used in the Artemis 5 mission, currently slated for 2030. Standing 16.3 metres tall and with a diameter of 3.8 metres with the ability to support up to 4 astronauts on the Moon for up to 30 days, that vehicle is called Blue Moon Mk 2, and much of its nature is already a matter of public record.

What is new to the mix, as revealed by John Couluris, Senior VP of Lunar Permanence at Blue Origin, speaking at a lunar symposium, is the confirmation that the company is going ahead with a cargo version of the Mk 2 lander.

This vehicle, which will replace the crew habitat facilities with payload space, is to have the ability to deliver up to 22 tonnes to the lunar surface if reused, or 30 tonnes if flown one-way – enough to deliver habitat modules to the Moon. It will join the company’s Blue Moon Mk 1 cargo vehicle to offer a flexible approach to delivering payloads to the Moon, the 8 metre tall Mk 1 having a payload capability of 3 tonnes.

The Mk 1 lander has also been in development for some time, and the first vehicle is currently due to fly to the Moon before the end of 2025. If successful, it will become the largest vehicle to land on the Moon to date with a mass of 21 tonnes, and the first lander to do so using cryogenic propulsion. A second Mk 1 lander is also under construction.

Transporter is now the name formally given to the Cislunar Transporter Blue Origin originally indicated they would be developing with Lockheed Martin. This would have been a two-stage vehicle, comprising a propulsion unit and a cryogenic fuel storage tank, each launched separately into low-Earth orbit (LEO) by Blue Origin’s New Glenn launcher, prior to them mating and the tank being filled with cryogenics delivered by further New Glenn Launches. The propulsion unit would then deliver the tank to cislunar space, allowing it to refuel landers operating between there and the lunar surface.

Under the new design, Blue Origin will be progressing Transporter on their own, and the vehicle will now be a combined propulsion unit and cryogenic propellant store capable of being launched atop a single New Glenn rocket. Once in orbit, the tanks would again be filled by propellants delivered by the upper stages of other New Glenn rockets. Just how many additional launches to do this will be required has not been made clear, but the intent is to have Transporter capable of delivering 100 tonnes of cryogenic propellants to cislunar space – and 30 tonnes to Mars.

However, one of the complications in using cryogenic propellants in lunar (and Mars) missions is that that of boil-off. Propellants like liquid oxygen, liquid hydrogen and liquid methane need to be kept extremely cold to avoid them turning to gas, thus increasing their volume and necessitating them being vented to avoid over-pressurising their containers. This is bad enough on Earth where the ambient temperatures aren’t that high; in space and direct sunlight, the problem is dramatically multiplied. One way of slowing the process is to slowly rotate the vehicle so that the same side is not always towards the Sun – a so-called barbeque roll – but it is limited in effect. Another is to add masses of insulation, but at the cost of payload capabilities.

Blue Origin is attempting to solve the issue by working with NASA to develop “zero-boiloff” technology capable of keeping both liquid hydrogen and liquid hydrogen – their preferred propellants – below their boiling points (−250.2 °C and −183 °C respectively). The company is currently testing this hardware within a thermal vacuum chamber, and Couluris indicated the company plan to start flight-testing the capability towards the end of 2025. If it works, and can maintain the required temperatures within large volumes of cryogenic propellants, it could be a major step in lunar operations.

Cruz to the Rescue?

On Friday, June 5th, Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas), chairman of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, on Friday (June 5) unveiled the Committee’s legislative directives for Senate Republicans’ budget reconciliation bill, with the aim of bolstering NASA’s budget in the face of massive cuts by the White House.

Well, at least the human spaceflight programme. The science programme gets barely a nod.

Geared as “beating China to the Moon and Mars” and ensuring “America dominates space”, the Committee calls for almost US $10 billion in supplemental funding for NASA, which would target:

- Continued funding of the Space Launch System (SLS) through to Artemis 5, without impacting the “on-ramping” of commercial crew launch alternatives (US $4.1 billion).

- Continued support for the development of Moon-orbiting Gateway station (US $2.6 billion).

- US $700 million for the procurement of a Mars Telecommunications Orbiter to take over primary Earth-Mars communications.

- US $20 million to complete the fourth of the planned Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicles (MPCV)

- US $1.25 billion over five years to fully and properly fund International Space Station (ISS) operations through until its decommissioning.

- Procurement of an ISS De-orbit Vehicle from SpaceX (US $325 million).

- US $1 billion for infrastructure improvements at the following NASA facilities: Johnson Space Centre – $300 million; Kennedy Space Centre – $250 million; Stennis Space Centre – $120 million; Marshall Space Flight Centre – $100 million; Michoud Assembly Facility – $30 million; $100 million for “infrastructure needed to beat China to Mars and the Moon”

The US $1 billion in infrastructure spending is around one-fifth of the estimated cost of clearing the backlog of improvements required at all of NASA’s centres, and (again) completely ignores the Earth and Space Science centres. Further, all of the above would be phased-in over a 3-year period, commencing in 2026 and running through 2029.

EscaPADE Mission Gets Launch Opportunity

NASA’s Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers (EscaPADE) mission, a pair of smallsats destined for Mars should have been launched in October 2024 as part of the payload for the maiden flight of Blue Origin’s New Glenn booster. However, NASA opted to remove the mission from that launch in September 2024, when it became apparent the New Glenn wouldn’t be ready to launch within the window required for the mission to reach Mars.

Since then, the mission has been awaiting a launch opportunity, with NASA looking at options for in 2025 and 2026 using complex trajectories that would enable the smallsats to reach Mars in 2027. One such potential launch opportunity is summer 2025, the period Blue Origin are looking towards for the next New Glenn launch.

These plans were stated as being aspirational at the start of May 2025, but a line NASA fiscal Year 2026 budget released by the White House on May 30th, provided the first confirmation that NASA is very much looking at an opportunity to launch this year.

Due to delays in the development schedule of the Blue Origin New Glenn launch vehicle, NASA is in the process of establishing an updated schedule and cost profile to enable this mission to ride on the second launch of New Glenn. The ESCAPADE launch readiness date is expected in Q4 FY 2025

– NASA Budget document, May 30th, 2025

Thus far, beyond saying it is hope to make the second flight with New Glenn in summer and are open to payload options (or flying a payload simulator), Blue Origin has said nothing about the overall status for the vehicle to be used in the flight. However, documents filed with the Federal Communications Commission requesting the use of certain ground frequencies from July 1st, indicate that the company intend to commence ground testing of the booster that month.