The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has been a pioneer in all fields of space exploration, planetary Sciences, Earth sciences, meteorology (alongside of its sister agency, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and its predecessor, the Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA)). It has also been responsible for many advances in aircraft systems and aviation safety ever since its formation in 1958.

NASA, like any bureaucracy, hasn’t always got things right. Nor has it always gone about things in the right way – Project Artemis currently standing as prime example of this. But, in term of its size and federal budget allocation, NASA is perhaps one of the most cost-effective and successful US federal organs in modern history, with an ability to achieve so much with what amounts to so little.

As an illustrations of what I mean by the above. In 66 years of operations, NASA’s budget has rarely exceeded 1% of the US federal budget in any given year. In fact its peek budgetary allocations came – unsurprisingly – in the era of Apollo, but even then only reached a peak of 4.41% of the total US budget (1966). By the start of this century, NASA’s budget represented just 0.80% of federal spending and was in decline as a whole. For the last 15 years it has stabilised, but has rarely exceeded 0.50%.

That’s a long way from being the kind of black hole of federal expenditure far too many people take it to be, and in terms of overall expenditure, NASA represents bloody good bang for the buck. Yet – and perhaps because of that incorrect public assumption – it remains a soft target with it comes to cutting the federal budget. Sometimes, admittedly, these cuts are driven by economic needs at the time, others are due political priorities pointing elsewhere. However, it is fair to say none have ever been driven a dogma of intentional deconstruction fuelled by ignorance; but that is what NASA is now facing under the current US administration’s budget proposals, leaked in part on April 11th, 2025.

These call for NASA’s budget to be reduced by 20% in the name of “cost-saving”. As the lion’s share of NASA’s budget – 50% in total – is devoted to all aspects of human spaceflight, and thus considered inviolable when it comes to cuts, the proposal directly targets NASA’s science, aeronautics, technology research and administrative budgets. They involve calls for the complete closure of at least one NASA research centre and a slashing on NASA’s overall science budget by as much as 50%.

There is nothing accidental about this targeting; the architect of the NASA cuts proposal is Russell Vought, one of those behind Project 2025, and a man known for his profound anti-science beliefs and doctrine. Such is his animosity – shared by others in the administration – towards subjects such as climate change, Earth observation and resource management, he is seemingly content to take a meat cleaver and hack off what is potentially NASA’s most cost-effective limb, one consistently responsible for delivering a wealth of invaluable knowledge to the world as a whole, simply to end the agency’s ability to carry out research into subjects he views with personal enmity.

Chief among these cuts is a two-thirds reduction in astrophysics spending (reduced to US $487 million); a 50% cut in heliophysics (down to US $455 million); more than 50% slashed from Earth sciences (down to just over US $1 billion) and 30% cut from planetary sciences (reduced to under US $2 billion).

The budget also specifically earmarks the Goddard Space Flight Centre (GSFC), NASA’s first and largest science facility, with a staff of 10,000, for closure. The rationale for this, again, appears to be GSFC’s involvement in climate studies. However, such is the breadth and depth of its work, any such closure would cripple much of NASA’s research and science capabilities – something I’ll come back to below.

Within NASA, the proposal – initially dismissed by acting Administrator Janet Petro as “rumours from really not credible sources” when word surfaced about it ahead of its publication – is now being regarded as an “extinction level event” for NASA’s entire science capability.

The proposal has drawn sharp response from Capitol Hill, including the bipartisan Congressional Planetary Science Caucus, together with threats to “block” the budget’s move through the Senate.

If enacted, these proposed cuts would demolish our space economy and workforce, threaten our national security and defence capabilities, and ultimately surrender the United States’ leadership in space, science, and technological innovation to our adversaries. We will work closely with our colleagues in Congress on a bipartisan basis to push back against these proposed cuts and program terminations and to ensure full and robust funding for NASA Science in Fiscal Year 2026 appropriations.

– Congressional Planetary Science Caucus statement

Nominee for the post of NASA Administrator, Jared Isaacman, who is going through his confirmation process during April and already facing questions over his relationship with the SpaceX CEO (who is already impacting NASA through his DOGE scheme and in trying to influence the White House’s thinking over projects such as the ISS), described the budget proposal as “not optimal”, and stated that if confirmed, he would advocate “for strong investment in space science—across astrophysics, planetary science, Earth science, lunar science, and heliophysics—and for securing as much funding as the government can reasonably allocate.”

But while there may well be vows to block the proposed cuts and to “advocate” for science, concern has already been raised at to how effective or real they might be. The Trump administration has established a strong track record for decision-making by fiat, bypassing Congress altogether – and Congress (notably the House) has been largely content to sit and watch the edicts from the White House whoosh by.

Under US law, there is the means for the Executive to arbitrarily impose budgets on federal agencies. The process is referred to as “impoundment”. In theory it can only be used following the start of the next government fiscal year – in this case, October 1st, 2025 – and then only if Congress and the White House remain at loggerheads over budgets. However, it has been reported that those in the White House see impoundment as a means to set budgets by executive decree, regardless of whether October 1st has been reached, in the expectation that should push come to shove, Congress will continue to sit on its hands.

GISS – First of 1,000 cuts?

Some proof of this might be evident in the case of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS). Established in May 1961, GISS is a research division of the Goddard Space Flight Centre, and since 1966 it has been located at the Armstrong Hall (named for Edwin Armstrong, not Neil), New York City.

In the decades since its establishment, GISS has become renowned for its Earth Sciences research across a variety of disciplines, including agriculture, crop growth and sustainability and climatology. It has built some of the largest dataset on current and past climate trends and fluctuations. It has also contributed to the fields of space research, both on a cosmological scale and through multiple NASA solar system missions from Mariner 5 to Cassini-Huygens. Researchers at the GISS have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics, the Heinz Award and the World Food Prize for contributions to physics, science, environmental awareness, and improving the availability of food around the world.

In other words, it is a major centre for US scientific achievement.

However, on April 25th, 2025, the Trump Administration summarily cancelled the lease on Armstrong Hall – operated by Columbia University – ending GISS’s tenure there as from May 31st 2025. Again, The reason for this has been given “government waste of taxpayer’s money” (the lease had a further 6 years to run at a cost of US $3.3 million a year) – but the aim appears to be ending the GISS’s ability to conduct climate research.

Responding to the news in an e-mail to staff, GSFC director Dr. Makenzie Lystrup stated a confidence that the work of the GISS will continue, as its value is in “data and personnel”, not location, and promised to find the GISS a new home. However, given that GSFC is itself under threat, it remains to be seen whether a long-term future can be found for GISS and its data. In the meantime, all GISS staff have been placed on “temporary remote working agreements”.

Hubble at 35

The news of budget reductions potentially hitting NASA’s science capabilities come at a time when arguably what is one of its most iconic missions – the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) – celebrates 35 years of almost continuous operations (allowing for down-times due to on-orbit servicing and the odd moments in “safe” modes as a result of on-board issues).

Launched in 1990, Hubble’s story is one of triumph over near-disaster. On reaching orbit, a tiny error on the manufacture of is 2.4 metre diameter primary mirror came into focus – or rather, out-of-focus. Polishing on the perimeter of the mirror meant it was “too flat” by some 2200 nanometres (that’s 1/450 mm, or 1/11000 in). While tiny, the error was catastrophic in terms of Hubble’s clarity of vision, and effectively ended any chance of it carrying out cosmological observations before they started.

Fortunately, as we all know, NASA had the space shuttle, and Hubble had been specifically designed to be launched and serviced by that vehicle. It was therefore possible to come up with an ingenious solution to correct the error in the primary mirror – not by replacing it, but by giving Hubble a pair of “glasses” to correct its vision.

The first “lens in the glasses” took the form of deliberately introducing errors into the optics of the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WF/PC-2), an instrument already in development at the time Hubble was launched, and due to replace a similar instrument already on the telescope. These errors would completely cancel out the defects in the mirror’s surface, allowing the camera to take the required super-high resolution images with complete clarity.

The second “lens in the glasses” was an entirely new instrument called COSTAR (Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement), designed to eliminate the mirror’s flaws from impacting the other science instruments on the telescope, until such time as these instruments could also be replaced by units with their own in-built corrective elements. COSTAR did require the removal of another instrument from Hubble – High Speed Photometer – but it meant Hubble would be able to carry out the vast majority of its science activities unimpeded.

In December 1993, the shuttle Endeavour delivered the WF/PC-2 and COSTAR to Hubble, where they were successfully installed. By 2002, subsequent servicing missions had successfully updated all of the remaining science instruments on Hubble, allowing COSTAR to be returned to Earth. This occurred in 2009 when the final shuttle servicing mission replaced COSTAR with the Cosmic Origins Spectroscope (COS).

Throughout its life, Hubble has made thousands of observations and contributed massively to science programmes, our understanding of our solar system, galaxy, and the greater cosmos. It has participated in studies conducted around the world and contributed to a huge volume of science and education endeavours. And despite failures, aging equipment and other issues, it repeatedly allows itself to be pulled out of every “safe” mode and resume operations through servicing missions and – since 2009 – via remote diagnostics and correction.

Such is its capacity to keep right on going, it is affectionately known as NASA’s Energiser Bunny by many in the programme.

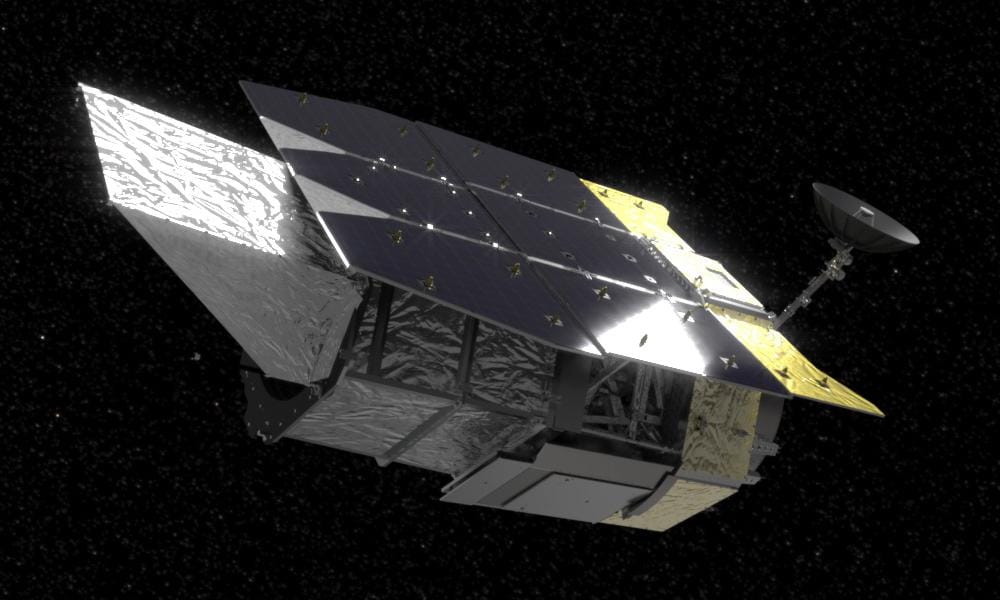

All of which is made all the more poignant by the fact that NASA’s entire space observatories mission is at risk of closure as a result of the proposed Trump budget. Hubble, together with its semi-siblings, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and Chandra X-ray Telescope (itself only saved from abandonment in March 2024) are all financed out of NASA’s Astrophysics budget, which the Trump administration wants to cut by 66%. Were this to happen, NASA would likely be unable to continue to operate all three telescopes – or even two of them – and certainly would be unable to complete and launch the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. And even if one or more of the observatories were to survive the cuts, all are dependent on the Goddard Space Flight Centre for their operational and engineering infrastructure and support – which again, the budget proposing closing, a move that would kill the telescopes.

Hopefully, none of this will happen, but one cannot deny the dark shroud it casts over Hubble’s anniversary.

NOAA As Well

As noted, one of the most unsettling aspects with the proposed NASA cuts is the idea that the White House might seek to impose cuts and reductions by fiat, bypassing Congress with the use of executive orders.

This threat, is given weight by the fact that an initial 800 employees of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) were abruptly fired at the end of February 2025 on the grounds of “cutting costs”, the fact that they were “probationary” employees being disingenuously used to suggest they somehow weren’t qualified to work at the agency. Currently, it appears that a further 1,000 positions at the agency still hang in the balance.

Nor does the threat to NOAA end there. The Trump budget proposal recommends cutting NOAA’s comparatively tiny US $7 billion budget by 25%. Specifically – and unsurprisingly – chief among the agency’s work targeted by the cuts is anything related to climate studies. In fact, in this area, the proposed cuts are closer to 75%, effectively ending all of NOAA’s research into climate change and weather (and no, the two are not the same).

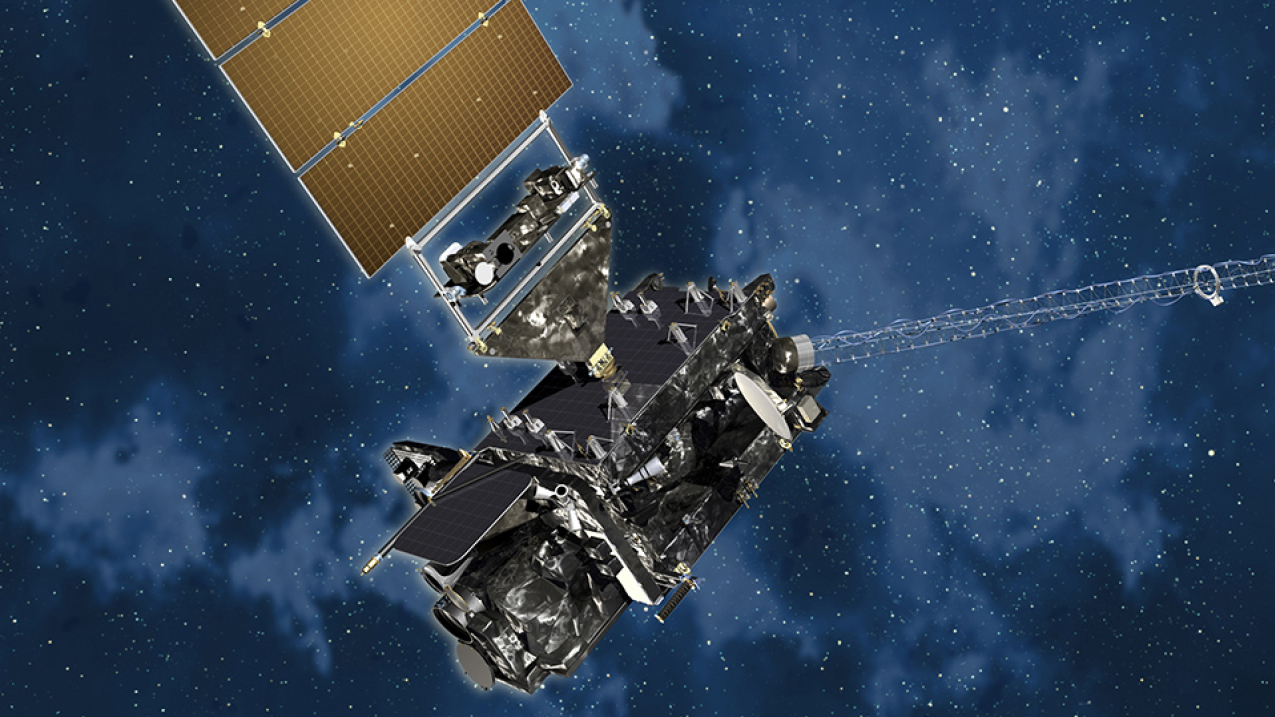

Although the administration has stated the National Weather Service will “not be touched”, both the layoffs in February and the proposed cuts could have potentially far-reaching impacts in that service’s capabilities. NOAA, in collaboration with NASA, currently operates three large Geostationary satellites for both weather forecasting and for gathering data on climate (called GOES). All three of the current units (only two of which are operational) are scheduled for replacement between 2032 and 2035. However, the Trump administration is also looking to end many joint ventures between NASA and NOAA. This, coupled with the proposed budget cuts means development of the replacement satellites could be impacted in the near future.

Further, by conflating “weather observations” with “climate change”, the administration has already severely impacted NOAA’s ability to carry out vital research into the development and operation of climate interactions that give rise to weather phenomena such as hurricanes.

NOAA was already stretched thin and understaffed. It’s going to go from stretched thin to decimated. NOAA provides most of the raw data and the models that predict hurricanes, and the hurricane forecasts many Americans see on their phones or TVs are created by the agency. Reducing the research and observation capabilities of the agency in this regard could regress hurricane forecasting capability by the equivalent of decades.

– Dr. Andrew Hazelton, former member of NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division.

All this comes at a time when the evidence for human activity being the single greatest release of greenhouse gasses into the environment, and thus the primary driver of climate change over and above any natural shifts in climate, are becoming more and more evident. As such, threats to Earth science budgets like those currently being proposed by the US administration, together with their headlong rush to increase US reliance on fossil fuels represents a further threat to our collective well-being.

Thank you for this Inara. As a resident of MD and a scientist, I did not know there might be a plan to close the Goddard Space Flight Centre (spelled ‘Center’ here ;). How terribly depressing.

LikeLike

Yeah… I was stunned to come across that news. I think Ars Technica is the only publication to directly pick up on it.

I use “Centre” because, well, English 🙂 – although technically I should use the *cough* “incorrect” spelling *cough* 😀 as it’s part of the facility’s name.

LikeLike