After delays related to a ground-side helium leak at the launch pad followed by a prediction of several days of poor weather in the region where the mission would splashdown at its conclusion, thus potentially hampering recovery operations if not put the crew and vehicle at outright risk, the Polaris Dawn private venture mission lifted-off from Kennedy Space Centre, Florida on September 10th, 2024.

The Falcon 9 rocket carrying Crew Dragon Resilience and its crew of four private citizens lead by billionaire Jared Isaacman, departed Launch Complex 39-A at 09:23 UTC at the start of an extreme 5-day mission in an extended elliptical orbit around the Earth with a number of potentially high-stakes goals, including the very first spacewalk by non-career astronauts.

The first part of the mission called for the capsule to be placed in an orbit of around 200km perigee and an apogee of 1,200 km. This required the first stage of the Falcon 9 booster to operate in expendable mode, running for some 12 minutes prior to separation, after which it fell back into the Atlantic Ocean. On arrival in their initial orbit, the crew commenced an extended period of pre-breathing an oxygen-rich atmospheric mix designed to remove nitrogen from their blood, organs and muscles.

Such pre-breathing (very similar in nature to that undertaken by divers going down to significant depths in the oceans) is a requirement of all EVA work, as space suits operate at very low pressures (e.g. roughly 5 psi compared to the average sea-level atmospheric pressure of 14.8 psi). If the nitrogen is not flushed from the body, it can bubble and cause decompression sickness, causing serious injury –and potentially death – to the sufferer as the pressure is raised back to normal levels.

Normally, such pre-breathing would be carried out only be the astronauts making the EVA, and they would use an airlock in which to do so, spending several hours undergoing the process. However, Crew Dragon does not have any form of airlock, so the entire vehicle must be depressurised, hence the entire crew going on the oxygen rich mix. As this happened, work also started on very slowly reducing the overall cabin pressure from 14.5 psi to 8.6 psi, a process that continued over the first three days of the mission leading up to the actual EVA.

After some eight orbits around the Earth, the Dragon’s motors fired, elevating its apogee to around 1,400 km above sea level. This marked the furthest anyone has been from Earth since Apollo 17 in 1972, whilst also breaking the highest altitude record for a crewed mission orbiting Earth, originally set by Gemini 11 in 1966.

Both the 1200 and 1400km limits of the orbit meant the vehicle would skirt the Van Allen radiation belts, periodically passing through the South Atlantic Anomaly. This meant that during their five days in space, all four crew would be exposed to the same amount of radiation an astronaut on the International Space Station (ISS – orbiting at an average of some 400 km) would require some three or more months to experience. Whilst such a concentrated exposure marked a great long-term risk to the health of the four, it formed part of the science programme for the mission.

In brief, radiation exposures as a fact of space travel, but despite all the work aboard the ISS and other orbital vehicles like the space shuttle on extended missions, there are numerous active factors of radiation exposure in space that are not clearly understood. To this end, Polaris Dawn flew a series of experiments put together by Translational Research Institute for Health (TRISH), a NASA-funded consortium of academic institutions specifically aimed at investigating some of the more usual aspects of space-based radiation exposure, in order to better understand them.

Polaris Dawn crewmembers participating in these TRISH studies will provide data about how spaceflight affects mental and physical health through a rigorous set of medical tests and scans completed before, after, and during the mission. The work will include assessments of behaviour, sleep, bone density, eye health, cognitive function and other factors, as well as analysis of blood, urine and respiration.

– NASA statement on the Polaris Dawn NASA-sponsored science

Much of this work will continue well after the mission’s conclusion, with studies and checks on their health and welfare continuing over the next few years.

In addition, the mission flew Tempus Pro, a commercial package NASA has been adapting for use on space missions. It is designed to collect collect multiple health measurements from astronauts and compare them with a database of medical data on Earth, allowing flight surgeons to more fully diagnose an astronaut’s overall physical and mental health and well-being. The system can also be used to provide real-time telemedicine support (including any consultations from specialist almost anywhere on Earth) to assist medical personnel on space missions in provide physical and mental treatment to their fellow crewmembers.

In all the mission carried a total of 36 experiments from 31 partner institutions around the world. However, it was the EVA – to be undertaken in turn by Isaacman as crew commander (and major financier, who originally flew the Inspiration4 private venture orbital flight in 2021, and which also utilised Crew Dragon capsule Resilience), and Sarah Gillis, the senior space operations engineer at SpaceX – which had captured the attention of the world ahead of the mission.

The EVA took place on Flight Day 3, after the vehicle’s orbit haf been lowered and circularised at some 730 km above sea level. It commenced some time in advance of the actual hatch opening, with a further round of pre-breathing a 100% oxygen atmosphere to purge remaining nitrogen from the astronauts’ bodies, and a slow final lowering of the cabin pressure prior to full venting. All four then donned their IVA / EVA suits and tested their umbilical life support and power feeds (the SpaceX suits do not operate with the kind of back-pack common to NASA / Roscosmos EVA suits, but are reliant on a physical connection to the space vehicle).

At 15:12 UTC on Thursday September 12th, 2024, all four crew reported their suits were sealed and operational, and they were operating entirely off of the life support reserves supplied to their suits. The final de-pressurisation of the capsule cabin could then commence, causing their suits to expand to their pressurised size. Some 37 minutes after final depressurisation had started, the vehicle was ready for the inner hatch to be unlatched by Isaacman, as EVA-1, and the pressure seal broken. This then allowed the hatch opening mechanism to be triggered, with the hatch sliding fully open at 15:56 UTC.

Isaacman then egressed through the nose chamber onto the “skywalker”, a special ladder-come-work platform with hand holds and foot restraints, design to allow a crew member to both raise themselves out of the nose of the craft and anchor their feet on the platform so that they can perform hands-free work.

A camera mounted on Resilience’s nose cone cap (which had been opened as per standard practice since the craft’s arrival in orbit to help with general heat regulation) filmed Isaacman as he emerged from the nose of the vehicle, initially rising to waist level before carrying out a range of mobility tests as the spacecraft raced over Australia and towards New Zealand and the terminator between the day and night sides of Earth.

The mobility tests were designed to test both ease and range of movement within a pressurised IVA / EVA suit, both with arms and legs, moving up and down the steps on the “skywalker”, testing the ease of use of the foot restraints, and the overall freedom of movement and reach allowed by the suits when in the near-vacuum of space. In all, Isaacman spent roughly 8 minutes on the platform before climbing back down into the capsule.

Sarah Gillis then replaced him, moving into the nose of the capsule and onto the “skywalker”. Unfortunately, shortly after she anchored herself on the “skywalker” to commence her own series of tests, Resilience passed out of video relay range of NASA Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS), so the live video feed was lost, leaving only verbal communications. However, she spent almost the same amount of time as Isaacman in her EVA, allowing her to give an engineer’s perspective on the usability of the suits.

By 16:21 UTC, Gillis was back inside Resilience and the inner hatch was closed, leaving Isaacman with the task of latching and locking it securely. Over the next 50 minutes, the pressure inside the vehicle was restored to a point where the crew could use the cabin’s atmosphere and start removing their IVA / EVA suits.

The EVA by the numbers (from space commentator Jonathan McDowell:

- Total elapsed time (starting when the capsule was fully depressurised through to being re-pressurised to approx 5 psi): 1 hour 46 minutes.

- Total “spacewalk time” (time from unlatching the inner hatch to re-latching it): 33 min 25 seconds.

- Total time Isaacman spent on the “skywalker” and outside the cabin: 7 minutes 56 minutes.

- Total time Gillis spent on the “skywalker” and outside the cabin: 7 minutes 15 seconds.

These may not be record-breaking numbers, but they are nevertheless extraordinary and of potential significance as a starting-point for such operations by non-career astronauts. Private venture EVA operations are bound to become more and more commonplace and of longer and more complex duration as the next generation of private / commercial orbital facilities by the likes of Axiom and the Blue Origin / Sierra Space led Orbital Reef consortium come on-stream.

The remaining two days of the mission saw the four astronauts resume their science work as cabin pressure within the vehicle was gradually brought back up to more reasonable pressures in advance of a return to Earth. As well as the science work, the crew also conducted tests in using the SpaceX Starlink satellite network for audio and video communications with mission control.

Part of the latter once again involved Sarah Gillis, who is also a classically-trained violinist. On September 13th, she performed of Rey’s Theme by legendary composer John Williams. Whilst the performance was misreported in some media as the “first” performance of a musical instrument in space (instruments have been played in space for decades; for example, Catherine Coleman played the flute on the ISS in 2011 and Chris Hadfield, commander of ISS Expedition 35 famously recorded a music video of David Bowie’s Space Oddity, marking it as the first music video ever shot in space), it was nevertheless still and important factor for the mission’s overall objectives.

One of the things Isaacman has done with her personal fortune and through his private space ventures is to raise money St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. In 2021, for example he both donated several million to the hospital and auctioned off seats on the Inspiration4 mission with the money raised going to the hospital. Gillis’ rendition of Rey’s Theme was combined with six orchestras from around the world to produce a recording and video entitled Harmony of Resilience to help raise further funds for the hospital from this mission.

As we travel around our beautiful planet Earth on this five-day mission, we wanted to share this special musical moment with you. Bringing together global talent, this performance symbolizes unity and hope, highlighting the resilience and potential of children everywhere.

– Sarah Gillis, September 13th, 2024, from orbit aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon Resilience

Polaris Dawn ended on Sunday, September 15th, 2024, with de-orbit operations starting at 06:34 UTC. These saw Resilience orient itself ready for atmospheric interface and jettison its service module – the Trunk, in SpaceX parlance to expose its heat shield. A series of thruster firings of the capsule’s Draco motors followed, slowing it velocity. These were completed by 06:50 UTC and the forward nose cone was swung back into its closed positions and latched.

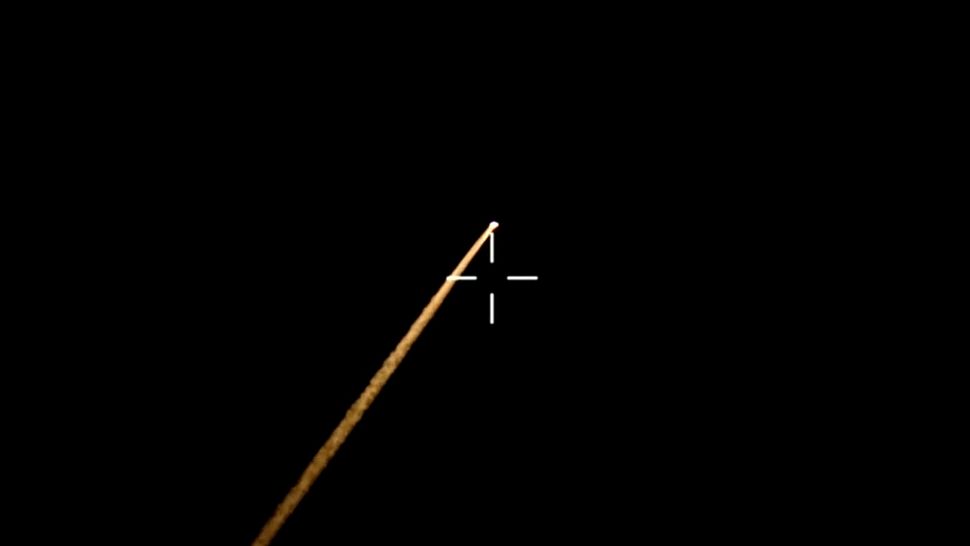

At 07:15 UTC, the vehicle reached interface and entered a roughly 7-minute period of descent through the upper atmosphere during which the vehicle experience peak frictional heating around it, together with a loss of communications. The track of Resilience meant it was not only caught on camera by recovery vessels in the Gulf of Mexico, but also seen by the crew of the ISS.

Things then proceeded rapidly. After re-entry, the vehicle’s drogue parachutes deployed so start slowing it, and not long afterwards, the four large main parachutes deployed, with Resilience splashing down at 07:37 UTC.

An initial safety and recovery team approached the capsule in a RHIB deployed by the SpaceX recovery vessel Bob (named for astronaut Bob Behnken, one of the first two people to fly a Crew Dragon to space (the other being Doug Hurley, who has the larger recovery ship Doug named for him) to confirm the capsule was safe and not venting harmful gasses. At the same time, additional RHIBs sought to recover the spacecraft’s parachutes.

With the confirmation all was safe, the recovery operation began, the RHIB team preparing Resilience for hoisting onto Bob’s stern deck as the recovery vessel slowly closed with the capsule to arrive alongside at 08:00 UTC. Eight minutes later, with the lifting lines secured, the loading arm at the stern of Bob raised the capsule up onto the ship’s deck, where it was moved forward to the egress platform under the cover of the ship’s helipad and at a height that allows for easier opening of the capsule’s hatch.

The latter was opened at 08:20 UTC, after a final round of checks, and the recovery ship’s surgeon entered the capsule to check on the overall condition of all four crew to ensure they were showing no signs of decompression sickness or other issues. After this, the crew were allowed to exit the vehicle, with SpaceX lead space operations and mission director Anna Menon the first to leave the capsule, followed by Sarah Gillis then pilot Scott Poteet and finally Isaacman. All were in a jubilant frame of mind – and rightly so.

Polaris Dawn was in many respects a high-stakes mission; Resilience had to be extensively modified for the flight – not just her forward nose area, but throughout, with electronics and other systems inside the vehicle being “hardened” for us in the near-vacuum of Earth orbit; the IVA / EVA suit, despite extensive testing on Earth was still unknown in terms of how it would work in space, and the crew themselves took on a lot in respect of future health and welfare through such an intense exposure to Earth’s radiation fields over so limited a time. In this latter aspect, the mission’s work will continue through post-flight research, as noted above.

Two more Polaris missions are in development, although their time frames and goals have yet to be confirmed. One will most likely involve another Crew Dragon flight, and Isaacman has stated he plans the third to be the first crewed flight of SpaceX’s Starship vehicle; so that one at least is unlikely to be in the immediate (and potentially foreseeable) future.