Boeing’s Starliner capsule Calypso is back on Earth after what appears to have been an almost pitch-perfect automated return flight form the International Space Station (ISS).

The vehicle departed the ISS at 22:04 UTC on September 6th, after almost a day of preparations during which Starliner’s inner hatches were sealed as was the hatch on the ISS’s Harmony docking adaptor, prior to the “vestibule” at the forward end of Calypso, containing the vehicle’s half of the docking mechanism, being slowly depressurised. Some time prior to the undocking, and while awaiting the formal ATP – authority to proceed – the two control rooms at Johnson space Centre, Texas, one for the ISS the other for Starliner, did a final go / no-go poll, after which ISS Flight Director Chloe Mehring called the station.

Station Houston space-to-ground 2 for Starliner undock.

Go ahead, we’re with ya.

Hey, Suni both the Starliner and the ISS flight control teams have polled GO for undock at this time. Expected undock time is 22:04 [UTC].

Okay, copy. 22:04. Hey, y’know, just looking at the flight control roster, and like wow! It is the all-star team! You guys, it IS time to bring Calypso home. You have GOT this! We have your backs, and you’ve got this. Bring her back to Earth.

– Exchange between Flight Director Chloe Mehring and astronaut Suni Williams on the ISS prior to Starliner’s departure.

ATP came at 22:02 UTC, and the 12 docking “hooks” on the ISS docking adaptor rotated to their “open” position, allowing springs on the Starliner’s docking mechanism to very gently push it away from the space station two minutes later. The use of such springs avoids the need for the vehicle to use its forward thrusters, potentially spraying ISS docking adaptor and hatch with toxic hydrazine exhaust gas.

Once the separation between station and vehicle had exceeded 5 metres, Starliner commenced a series of 12 short firings of the forward facing reaction control thrusters on the service module, pushing itself outside the 200-metre Keep Out Sphere (KOS), an imaginary zone around the ISS within which a spacecraft must be on what is called a “4-orbit safe free drift trajectory”, meaning that it can float freely in close proximity with the station for a period of 4 orbits (roughly 6 hours) without any risk of collision should its manoeuvring system fail.

These burns were more or less a “reversing manoeuvre” in a straight line. Once outside the KOS, Starliner was within the larger Approach Ellipsoid (AE), another imaginary area of space around the station within which spacecraft must be able to float freely for up to 24 hours without risk of impacting the space station. Once in the AE, Starliner continued to move away from the station whilst starting to raise its orbit until some 19 minutes after undocking, it was clear of the AE as well and moving on to an orbit that would carry it around the Earth several times and bring it to the required position for its de-orbit burn.

Once clear of the AE, the ISS involvement in the flight concluded, leaving the NASA Starliner flight team to oversee the rest of the return, an operation of multiple parts.

In particular, the Calypso’s own Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters were tested. Entirely separate from the problematic thruster systems on the service module, Calypso’s RCS allow the capsule to manoeuvre and maintain orientation once it has separated from the service module after the de-orbit burn, in order for it to successfully re-enter the denser atmosphere. These 12 thrusters are divided to two “strings” of 6, with only one “string” being used in flight operations, the other being there for redundancy purposes. One of the thrusters did fail to fire during the tests, but posed no threat to the flight.

Similar redundancy exists within the service module RCS (hence why it has 28 thrusters in 4 banks of 7 apiece), and a test of 10 of the unused RCS thrusters on the service module during the same period saw them all operate without a hitch.

Then, immediately prior to the de-orbit burn was due to commence, a final weather check was carried out over the landing zone to confirm everything was above the required minimums for a Starliner landing. These checks include ensuring that winds be no greater than 12 knots, temperatures at ground level will be no lower the -9.4ºC, and the cloud base must not be lower that approx. 300 metres and allow for an all-round visibility of no less than 1.85 km (1 nautical mile). It must also be confirmed that there are no thunder or electrical storms within a 35.4 km radius centred on the landing zone which might interfere with data transmissions / reception. Should any of these criteria not be met, the de-orbit burn would be postponed until such time as all could be met.

As it was, everything was well within tolerances at the landing zone, and at approximate 03:15 UTC, four OMACS – orbital manoeuvring and Attitude Control System– motors on the service module fired in a 59-second burn, with several RCS thrusters also firing to maintain the vehicles overall orientation and attitude, slowing the vehicle sufficiently for natural drag to start pulling it into the denser atmosphere.

Immediately following the de-orbit burn, Calypso separated from the service module and oriented itself so the primary heat shield was at the correct entry for atmospheric interface, whilst the service module dropped into an uncontrolled re-entry so it would burn-up in the atmosphere and any surviving debris full into the southern Pacific Ocean. Calypso reached its re-entry interface – the period when it passed into the upper reaches of the denser atmosphere and experienced maximum re-entry temperatures – some 15 minutes after jettisoning the service module, and as it approach California’s Baja Peninsula. After this, things happened rapidly.

At 22km altitude, the forward heat shield at the top of the capsule was jettisoned, clearing the way for parachute deployment. This commenced almost immediately with the deployment of the vehicle’s two drogue parachutes, designed to help reduce its speed. These opened slowly over a 28-second period in order to reduce the stress on their canopies and the degree of sudden deceleration on the vehicle.

The drogues were in turn released at 10km altitude, allowing the three main parachutes to deploy and open over a 16-second period, again to reduce the strain on them and the vehicle. They then carried Calypso down towards landing. With a couple of hundred metres left in the descent, the primary heat shield was released, exposing the six airbags sitting between it and the base of the capsule, allowing them to rapidly inflate to cushion the actual landing.

Touchdown came at 04:01 UTC on September 7th, and the recovery teams started their operations shortly after, moving in to the landing site from upwind of the vehicle to avoid risk of any harmful gases from the propulsion systems, etc. Safing of the vehicle and preparing it for transit away from the landing zone proceeded over the course of the next several hours.

With Calypso now on Earth, the focus will shift to trying to rectify the causes of the issues with the service module propulsion systems. As I’ve previously noted, this is made harder as engineers have no physical parts to eyeball; they will have to continue to work on data gathered through ground testing of identical units and data gathered during all the test-firings performed during the flight (including those carried out during the vehicle’s return to Earth).

Calypso, meanwhile, with two flights under her belt, will now return to Boeing for a thorough check-out, overhaul and refurbishment. Although when she or the unnamed Capsule S2 (which performed the seconded uncrewed flight test to the ISS in 2022) will fly again is unclear. Currently, S2 is scheduled to fly the first Starliner operational mission (Starliner-1) in August 2025; however, NASA is now hedging its bets: it has recently double-booked the SpaceX Crew Dragon Crew-11 mission (crew yet to be assigned) to fly in the same period if it becomes apparent Starliner-1 will not be ready to fly.

As previously noted, this means that astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams will be remaining aboard the ISS until February / March 2025, when they will return to Earth on the SpaceX Crew Dragon Freedom. This is due to lift-off from Kennedy Space Centre on or around September 24th, carrying astronaut Nicklaus “Nick” Hague, and cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov to the ISS, where they will complete a 5-day hand-over with the Crew 8 team. The latter are set to depart the ISS around October 1st.

However, Crew 9 will not be the first the reach the station following Starliner’s departure. Soyuz TM-26 is to due to depart the Baikonur Cosmodrome on September 11th, carrying cosmonauts Aleksey Ovchinin and Ivan Vagner, and NASA astronaut Don Pettit.

They will dock with the ISS a few hours later, after a “fast” ascent and rendezvous, and raise the total crew on the ISS to 12. Then on September 24th (the day NASA is targeting for the launch of Crew 9 / Expedition 72), Soyuz TM-25 is set to depart the station and bring Oleg Kononenko, Nikolai Chub, and NASA astronaut Tracy Caldwell-Dyson back to Earth .

Blue Origin Advances New Glenn Maiden Flight, But Without NASA’s EscaPADE

Blue Origin is progressing toward the maiden flight of its New Glenn semi-reusable medium-to-heavy lift launch vehicle – although there are doubts about whether the company will meet the mid-October launch window NASA originally set it.

On September 3rd, the company deployed the new rocket’s 23m tall second stage to its launch facilities at Cape Canaveral Space force Station, Florida, where it will undergo a static fire test of its two Blue Origin BE-3U motors. However, this is just one of a number of milestones the company must meet in very short order if it is to make the mid-October launch window they state they still intend to meet.

This date was set by NASA when Blue Origin offered the flight as the launch vehicle for NASA’s EscaPADE Mars orbiter mission. A part of NASA’s Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx) programme, whereby missions costs are to be reduced by launching them as secondary payloads alongside primary missions, thus reducing their launch costs.

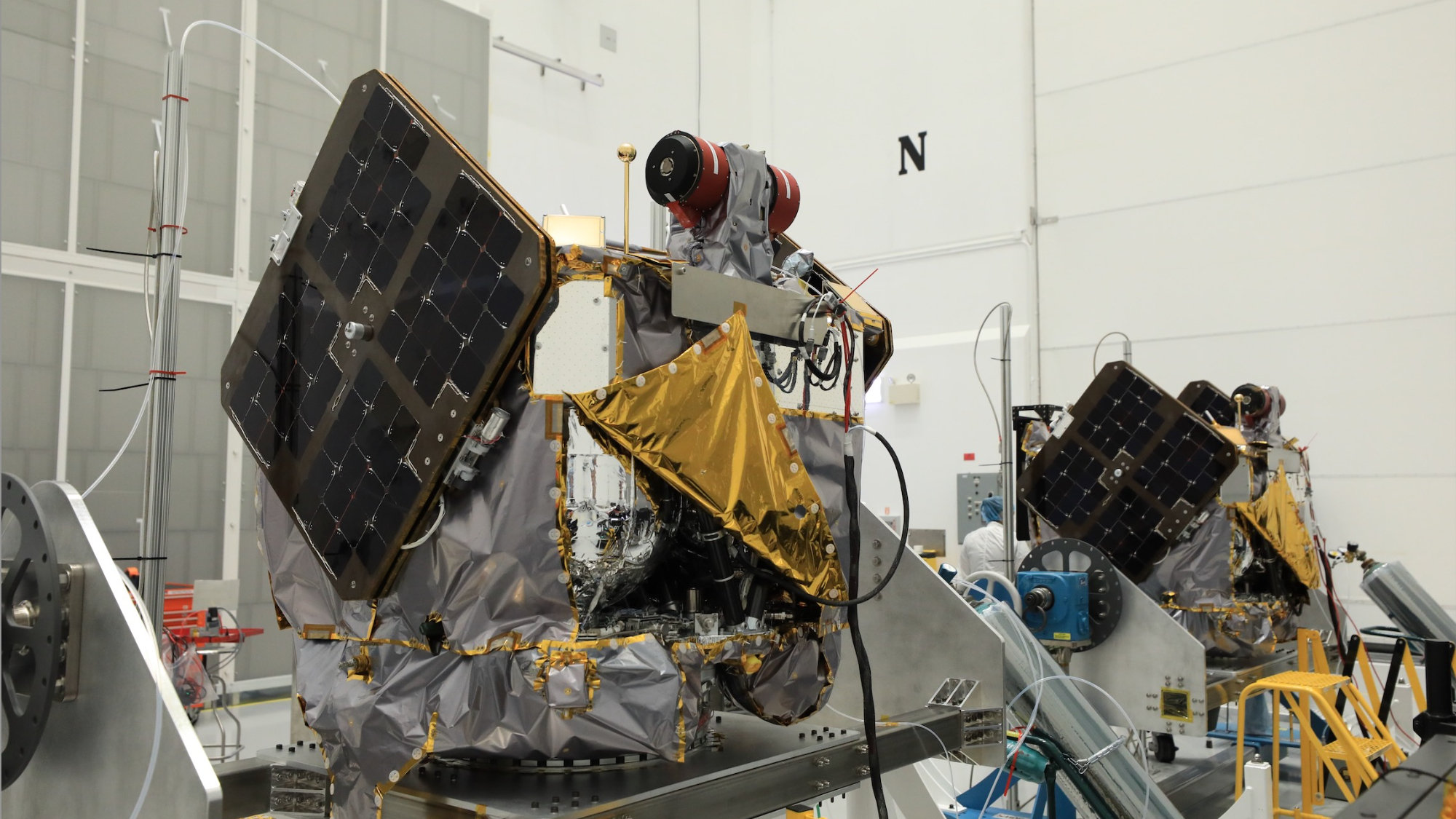

In this, EscaPADE – standing for Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers – a pair of identical satellites designed to study Mars’ atmosphere, were supposed to be launched with NASA’s Psyche mission, which originally was going to make a fly-by of Mars whilst heading for asteroid 16 Psyche, eliminating virtually all launch costs. However, Pysche’s launch was revised to a point where the Mars fly-by was no longer possible, and EscaPADE needed a new ride.

The New Glenn second stage raised to its vertical position on on the static fire test stand, Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. Credit: Blue OriginWhile Blue Origin offered the maiden flight of New Glenn at the bargain basement price of $20 million, it was still more that the original budget for the mission. With the launch facing a host of deadlines, including the second stage static fire test, and things like the integration and testing of the vehicle’s seven first stage BE-4 engines; stacking and integration of the vehicle’s two stages together with the payload and payload fairing; pad roll-out and countdown demonstration tests, NASA has been understandably concerned about Blue Origin’s ability to make the launch window for the last couple of months.

These concerns gained momentum because in order for EscaPADE to be ready for the launch, both satellites must be loaded within toxic hypergolic propellants. This is a costly, time-consuming exercise, and if New Glenn cannot make the October launch window, then NASA will have to go through an equally costly and delicate “de-tanking” exercise and purging of the propellant tanks of the satellites – and then go through the process again when the mission is ready for launch. So the decision was taken to avoid the additional costs and pull EscaPADE from the New Glenn launch. Instead, the agency is looking to launch the mission in spring 2025 – but still using a New Glenn vehicle.

This in itself has raised eyebrows; optimal launch windows to Mars occur around every 26 months, which spring 2025 does not meet. As such, it currently looks as if EscaPADE, a 990 kg all-up weight – will be the sole payload for the launcher, which will have to throw it into a heliocentric orbit around the Sun and out to Mars on an extended transfer flight.

In the meantime, and as noted, Blue Origin have stated they are still aiming to launch New Glenn on its maiden flight in October. With the removal of EscaPADE, they now intend to use the launch to place its Blue Ring “space tug” into orbit. This is a vehicle at the centre of a new operation for Blue Origin – providing on-orbit maintenance and movement of satellites. The company is also talking to the US government about using the flight to certify New Glenn as National Security Space Launch system.

As a semi-reusable vehicle, the first stage of New Glenn is designed to be able to land after each use. To achieve this, it will use a sea-going landing barge akin to, but larger than, the SpaceX autonomous drone ship landing platforms. Officially called a landing platform vessel (LPV), the first of these barges arrived at Port Canaveral at the start of September 2024 in readiness for the maiden flight of New Glenn.

Built in Romania and outfitted and commissioned in France, LPV-1 Jacklyn, named for the mother of Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos (who has also personally financed the company), the 115-metre long platform has already caused raised eyebrows as it has four large structures fore and aft of the 45m wide landing area. It’s not clear if these are integral to the barge (although the do seem to be) and what they might be for.

Certainly, putting such large structures on the barge is an interesting choice. Trying to successfully land a tall, thin tube containing the remnants of liquids that like to go kaboom when mixed and given the excuse, is not exactly a sinecure (just ask SpaceX). As such, hemming-in the landing zone with tall structures that could cause an even greater conflagration were a booster stage to topple into them whilst going the way of said kaboom seems to be somewhat tempting fate; I guess time will tell on that.