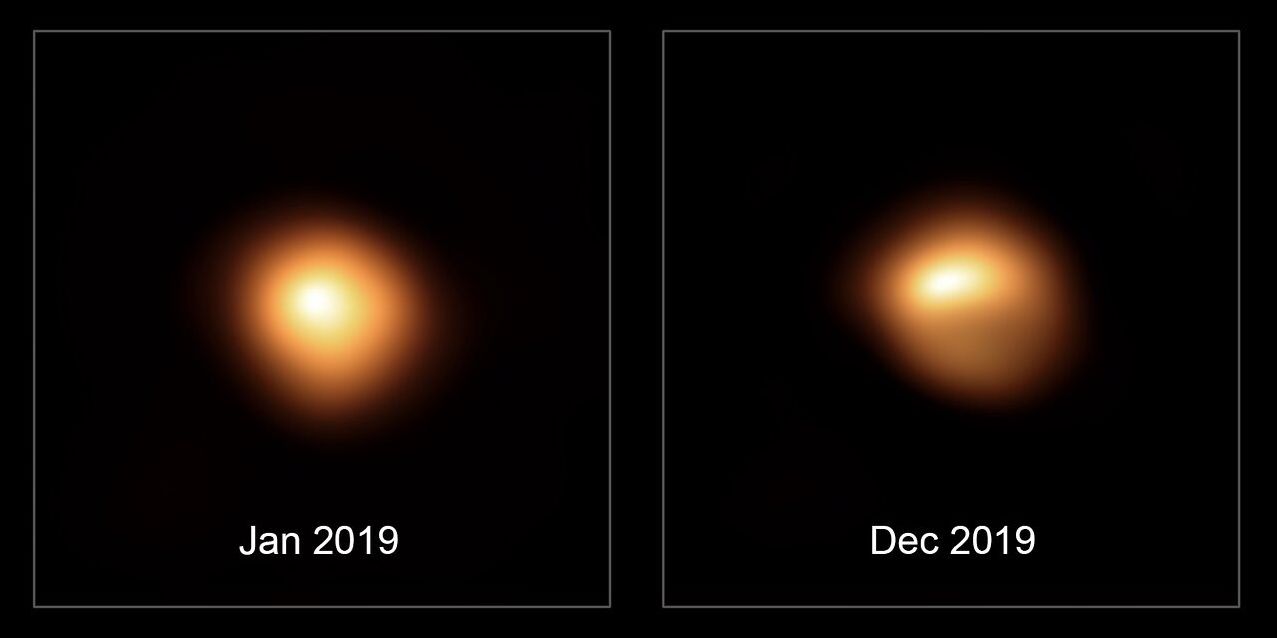

Back in 2019 / 2020 the red giant star Betelgeuse caused considerable excitement among astronomers on account of it undergoing a period of exceptional dimming – far more than is customary, given it is a pulsating variable star – which fuelled speculation that what was being seen might be the precursor to the star having gone supernova some 643 years ago (that being the time it takes for light from it to reach us), and the dimming was actually the star going through the kind of collapse the comes before such a supernova explosion.

However, despite the rapid and unusual dimming witnessed over December 2019, January 2020 and February 2020, by April 2020, the star had returned to its normal levels of brightness, and by August of that year, astronomers thought that had an explanation for the unwarranted dimming: the star’s pulsating nature gives rise to clouds of energetic particles to be ejected, some of which form a illuminate cloud around the star whilst more cool and form a blotchy cloud too dim an cold to be detected by optical or infrared means, and which can result in the star dimming significantly in addition to any normal variations in its brightness as see from Earth.

Because of the “great dimming”, astronomers have continued to observe Betelgeuse and gather a lot more data about it, particularly with regards to trying to understand the drivers of the star’s Long Secondary Period (LSP) of variability. Stars like Betelgeuse tend to have overlapping periods of variability: the first tends to be a fairly short cycle of dimming and brightening. In the case of Betelgeuse, this cycle of dimming and brightening again lasts some 425 days.

This overlaps a much longer period of variability – the LSP – which in the case of Betelgeuse lasts somewhere in the region of 2,100 terrestrial days, or roughly 6 years. These periods, short and long, can occasionally synchronise so that both reach a period of maximum dimness or brightness. Originally, it had be thought that such a period of synchronicity had caused with the 2019/2020 “great dimming”, until data and observations showed otherwise. However, and more to the point, the actual mechanisms which cause LSPs for variable red giant stars is not well understood, and have been ascribed to several potential causes.

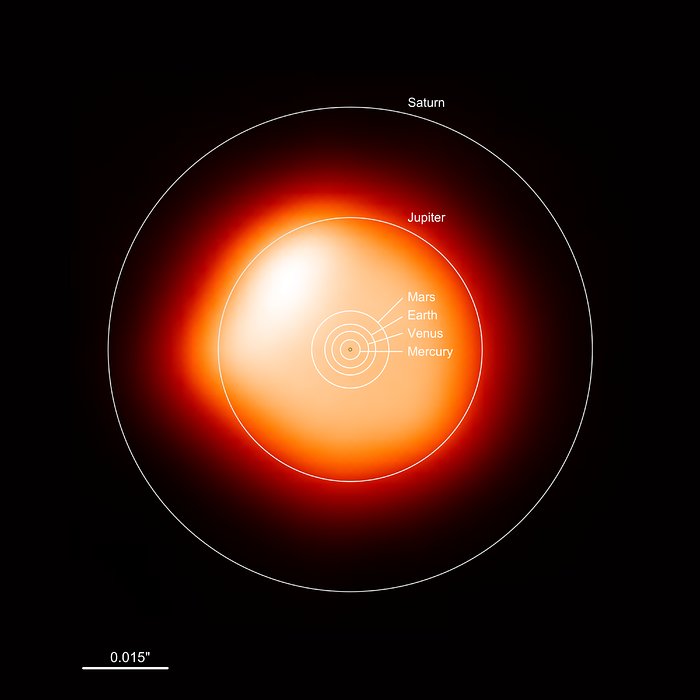

One of these is the potential for the red giant to have a smaller companion star, one very hard to observe due to the behaviour and brightness of the red giant. Such is the conclusion reached in a new paper: A Buddy for Betelgeuse: Binarity as the Origin of the Long Secondary Period in α Orionis published via arxiv.org (and thus still subject to peer review). In it, researchers Jared A. Goldberg, Meridith Joyce and László Molnár walk through all of the accepted explanations for LSPs among red giant stars as they might be applied to Betelgeuse, concluding that perhaps the most likely is that the red giant has a very low-mass (comparatively speaking) companion orbiting it at roughly 2.43 times the radius of Betelgeuse.

This puts the companion within the observable and illuminated dust cloud around Betelgeuse, potentially making the companion – referred to as α Ori B – exceptionally hard to observe, as it would be subsumed in the brightness of the surrounding dust and Betelgeuse’s own corona. further, it would be unlikely to form its own accretion disk, something which might otherwise aid its observation.

In particular, the paper notes that such a low-mass companion orbiting at the calculated distance from the red giant would actually give rise to an LSP of some 2,000-2,100 days as seen from Earth.

The one wrinkle in the idea – as noted by the authors – is that the calculated mass for α Ori B is well in excess of the calculated potential mass for such theoretical binary companions as provided by established (and peer-reviewed) papers investigating possible causes for LSPs among variable red giants. As such, and given the unlikely ability to optically identify any companion to Betelgeuse, the paper’s authors outline upcoming periods when α Ori B might be particularly susceptible to detection via repeated targeted radio-interferometric observations, in the hope their theory might be proven or disproven.

But why is all this important? Well, notably because Betelgeuse, at around 10-12 million years of age, could have entered the period in which it might go supernova (such massive stars evolve and age much more quickly than main sequence stars like our on Sun). When it does so, even though it is over 640 light years away, it will shine in the night sky with a brightness equivalent to that of the half Moon for a period in excess of three months before it fades away; hence why the “great dimming” caused so much excitement.

However, we could equally be as much as 100,000 years from such an event occurring. By understanding precisely what is going on around Betelgeuse, such as the presence of a cooler, darker dust cloud orbiting it affecting its brightness and as potentially found by the Hubble Space Telescope, or confirmation that the star has a smaller companion which plays a role in its cyclical brightening and dimming, astronomers are better available to judge whether or not any prolonged or unusual dimming of the star might indicate it has started collapsing in on itself and is heading for a supernova explosion – or are simply the result of expected and identified events unrelated to any such collapse.

New Shepard Aces Return to Flight Mission

Blue Origin took six people, including a NASA-funded researcher, on a New Shepard suborbital spaceflight on August 29th, the first such flight after issues have kept the system grounded almost continuously for two years.

The NS-26 flight carried its occupants to an altitude of 105.2 km, thus passing through the Kármán line, which is seen by some as the “boundary” between Earth and space at 100km above mean sea level. Interestingly, whilst named for Theodore von Kármán, the limit was not actually defined by him; instead, he calculated a theoretical altitude for aeroplane flight at 83.8 km (52.1miles) above mean sea level, which has led to 80 km (50 miles) also being regarded as the “boundary” between the denser atmosphere and space – however, some nations and organisations raised this to 100km based on calculations which showed that any satellite dropping to or below that altitude without any attempt to boost its orbit will see its trajectory decay before it can complete one more orbit.

The flight, which took off from Blue Origin’s Launch Site One in West Texas at 13:07 UTC, lasted 10 minutes and 8 seconds, the New Shepard booster safely landing some 7 minutes 18 seconds after launch, having separated from the capsule First Step, which continued upwards under ballistic flight. Aboard the flight were six people, including Robert Ferl, a University of Florida professor who conducted experiments on how gene expression in one type of plant changes when exposed to different phases of the the flight, including microgravity.

Also aboard was Karsen Kitchen, a 21-year-old University of North Carolina student, who became the youngest woman to cross the Kármán Line – but not necessarily the youngest woman to reach the edge of space; in August 2023, Eighteen-year-old Anastatia Mayers flew aboard Virgin Galactic 02 and passed through the 80-km “boundary” (also becoming one half of the first mother-daughter duo to reach the edge of space with her mother, Keisha Schahaff).

The remaining passengers on NS-26 comprised Nicolina Elrick, a philanthropist and entrepreneur; Ephraim Rabin, an American-Israeli businessman and philanthropist; Eugene Grin, who works in real estate and finance; and Eiman Jahangir, a cardiologist and Vanderbilt University associate professor (making a sponsored flight, rather than for research, his seat paid for via cryptocurrency group MoonDAO).

As noted, the flight came after almost two years New Shepard during which the vehicles barely flew. In September 2022 Blue Origin launched the first of 2 planned uncrewed flights – NS-23 – utilising the capsule RSS H.G. Wells carrying a science payload. During ascent, the booster’s main engine failed, triggering the capsule launch escape system. Whilst the capsule successfully escaped and made a safe landing under parachute, the booster was lost, resulting in the system being ground for investigation.

It was not until December 2023 that flights initially resume, again with a payload-carrying science mission. However, whilst successful, that flight was followed by crew-carrying NS-25 in May 2024. While no-one was injured, this flight suffered a partial deployment failure with one of the capsule’s three main parachutes, prompting a further grounding whilst the matter was investigated and remedial actions taken. NS-26 is thus the first flight since that investigation and subsequent work on the parachute systems had been completed.

For Ferl, the flight was a vindication of the value of sub-orbital flight to carry out research, despite their brevity. A long-time advocate of the use of sub-orbital crewed flights for carrying out packets of research , his work was funded by NASA’s Flight Opportunities programme and supported by the agency’s Biological and Physical Sciences Division, and marked him as the first NASA-funded researcher to go on such a flight.

Brief Updates

Polaris Dawn

The first all-private citizen spaceflight scheduled to include a spacewalk by two of the crew is currently “indefinitely” postponed – although that could now once again change fairly soon.

As I noted in my previous Space Sunday article, the mission, financed by billionaire Jared Issacman and to be carried out using a SpaceX Falcon 9 launcher and the Crew Dragon Resilience, had been scheduled for lift-off from Kennedy Space Centre at 07:38 UTC on the morning of August 27th. However, the launch was scrubbed as a result of a helium leak being detected in the quick disconnect umbilical (QDU) that connects the propellant feed lines to the launch vehicle. Helium is used to safely purge such systems of dangerous gases that might otherwise ignite. Ironically, helium leaks are a part of the issues which have plagued the Boeing Starliner at the ISS.

The launch was initially re-scheduled for August 28th, but this was then called off as a result of weather forecasts indicating conditions in the splashdown area for the capsule at the end of the mission would likely be unfavourable for a safe recovery and would probably remain so for several days. As the Crew Dragon will be carrying limited consumables for the crew and so cannot remain in orbit for an extended period, it is essential it is able to make a return to Earth and safe splashdown within n a limited time frame.

It was then postponed altogether later on August 28th after the longest-serving core stage of a Falcon 9, B1062 with 22 previous launches and landings to its credit, toppled over and exploded whilst attempting its 23rd landing – this one aboard the autonomous drone ship A Shortfall of Gravitas. The accident prompted the US Federation Aviation Administration to suspend the Falcon 9 launch license pending a mishap investigation. However, following a request from SpaceX, the license was reinstated on August 30th, allowing launches to resume whilst the FAA continues its investigation into B1062’s loss.

SpaceX has yet to indicate when the Polaris Dawn mission might launch, with much depending on other operational requirements both for SpaceX and at Kennedy Space Centre.

Starliner Update: One Down, Two Up

Again in my previous Space Sunday article, I updated on the Boeing Starliner situation and NASA’s decision not to have astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams fly the beleaguered craft back to Earth. At that time, it had been decided to fly the next crewed flight – Crew 9 / Expedition 72 – to the International Space Station (ISS) with just two crew, leaving two seats on the Crew Dragon vehicle available to bring Williams and Witmore back to Earth at the end of that mission in February / March 2025.

Since then, NASA has confirmed that the two members of Expedition 72 who will launch on the Crew 9 flight will be NASA astronaut Tyler Nicklaus “Nick” Hague, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Aleksandr Vladimirovich Gorbunov. I’d previous pointed to Hague making the flight, but had pegged mission commander Zena Cardman as flying with him. However, in order to keep the seating agreement with Roscosmos (who provide seats to NASA on their Soyuz craft flying to the ISS in return for NASA reciprocating with their flights), rookie Gorbunov was first announced as flying the mission, with Hague taking over the Commander’s seat on the basis of experience – he has flown into space previously aboard Soyuz TM-12, whereas Crew 9 would be Cardman’s first flight, and NASA does not fly all-rookie crews.

In fact, Hague has had something of an exciting time in his NASA career: his very first launch was on Soyuz TM-10 (Expedition 57) in October 2018 – only for that mission to suffer a booster failure mid-ascent to orbit. This triggered the crew escape system, which pushed the capsule containing Hague and mission commander Aleksey Ovchinin clear of the booster prior to the later breaking up, and then make a safe return to Earth under the capsule’s parachutes.

Currently, Crew 9 is slated for launch no earlier that September 24th.

Prior to that, and somewhat sooner than may have been expected, Boeing will attempt to bring their Starliner capsule Calypso back to Earth safely on September 6th. The announcement was made on August 29th, Boeing having indicated earlier in the month that it would take “several weeks” to prepare and upload the required software to the vehicle. Under the plan, the craft to undock from the ISS at 22:04 UTC on Friday, September 6th, and then complete a 6-hour return to Earth, the capsule landing at White Sands Space Harbour in New Mexico at 04:03 UTC. If this schedule holds, the vehicle will have spent exactly 3 months at the ISS on what should have been a week-long flight.

Of particular concern during the return attempt will be the performance of the vehicle’s primary propulsion thrusters, mounted on the Starliner’s service module. These are required for the vehicle to manoeuvre accurately and complete critical de-orbit burns prior to the service module being jettisoned to leave the Calypso capsule free to re-enter the atmosphere and make its descent.

Should the return be successful, it will enable engineers to carry out a complete assessment of the capsule and its systems to assess how it stood up to its unexpectedly extended stay at the ISS. However, determining what needs to be done to overcome the propulsion systems issues might take longer to resolve, as Boeing and Aerojet Rocketdyne (who built the thrusters systems on the service module) will only have data to work from – as the service module will be jettisoned to burn-up in the atmosphere, they will not be able to eyeball the faulty elements to determine more directly where root causes lay. Only after this work has been completed is it likely that Starliner will again carry a crew – although whether this is as part of an operational flight or as a second crew flight test (possibly completed at Boeing’s expense), remains to be seen.